FILM STUDIES - E

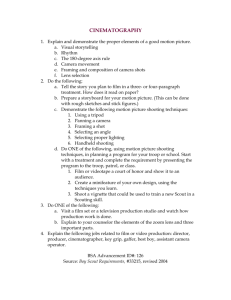

advertisement