kuliah 1 - FK UWKS 2012 C

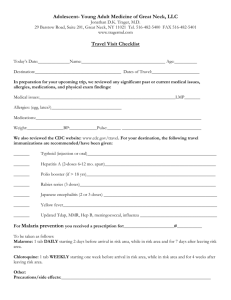

advertisement

KULIAH GASTROENTEROLOGI SUKENDRO SENDJAJA NYERI ABDOMEN Nyeri visceral NYERI ABDOMEN Nyeri tekan pada abdomen KULIAH GASTROENTEROLOGI Penyakit Saluran Cerna Atas Disfagia Dispepsia Helicobacter pylori Tukak peptik Penyakit refluks gastroesofageal (GERD) Penyakit saluran Cerna Bawah GANGGUAN ESOFAGUS DAN GASTER •D I S F A G I A •D I S P E P S I A •P E N Y A K I T R E F L U K S G A S T R O E S O F A G U S ( G E R D ) •P E N Y A K I T U L K U S P E P T I K U M •P E R D A R A H A N G A S T R O I N T E S T I N A L DISFAGIA Definisi Sensasi gangguan pasase makanan dari mulut ke lambung. Harus dibedakan dengan odinofagia (rasa sakit waktu menelan). Diagnostik Barium meal (esofagografi). Esofagogastroduodenoskopi (EGD). Pemantauan pH esofagus atau manometri esofagus. DISFAGIA Etiologi DISPEPSIA Dispepsia adalah keluhan nyeri (“abdominal pain”) atau perasaan tak enak (“abdominal discomfort”) yang bersifat menetap atau berulang, di daerah epigastrium. Keluhan ini dapat disertai rasa pedih, panas, kembung, mual, muntah, cepat kenyang, tak suka makan dan pengeluaran gas yang berlebihan (bersendawa) (Roma II) Dispepsia bukanlah suatu penyakit tetapi suatu sindrom yang harus dicari penyebabnya. PEMBAGIAN 1. Kelainan patologi 2. Keluhan pasien(Roma II) 1.1. Dispepsia fungsional 2.1. Tipe tukak (“ulcer-like”) 1.2. Dispepsia organik 2.2. Tipe dismotilitas (“dysmotility-like”) 2.3. Tipe nonspesifik (“unspecified”) DISPEPSIA FUNGSIONAL (ROMA III – 2006) B1. Dispepsia Fungsional •B1a: Sindroma Distres Pasca-makan (Postprandial Distress Syndrome = PDS). •B1b: Sindroma Nyeri Epigastrium (Epigastric Pain Syndrome = EPS). DISPEPSIA NON-TUKAK Dyspepsia non tukak (“non-ulcer dyspepsia”) atau dispepsia fungsional : bila pada pemeriksaan tidak ditemukan kelainan organik, baik : klinik, endoskopik, biokimia, maupun ultrasonografi (mis : tukak peptik, refluks gastro-esofageal, pankreatitis, dsb), minimal selama 3 bulan dalam 6 bulan terakhir (Kriteria Roma III – 2006). Gastritis dengan/tanpa infeksi kuman Helicobacter pylori termasuk dispepsia non tukak. Activity of secretory cells of the gastric mucosa PATOGENESIS DISPEPSIA Mekanisme yang menimbulkan keluhan dispepsia masih belum jelas. Beberapa teori : 1. Asam lambung 2. Motilitas 3. Gangguan fungsi sensoris 4. Kejiwaan 5. Post-infeksi kuman H. pylori 6. Duodenitis 7. Diit dan lingkungan PATOGENESIS 1. Asam lambung Peka terhadap asam lambung. Gastric Releasing Peptide (GRP) pada NUD dg HP (+) > orang sehat dg HP (+). Tipe tukak (ulcer-like dyspepsia). 2. Motilitas 40% NUD terdapat keterlambatan pengosongan lambung untuk makanan padat. 25-50% hipomotilitas antrum post prandial. Tipe dismotilitas (dysmotility-like dyspepsia). Penyebab : kuman H.pylory, refluks gastroduodenal, hormonal (DM), stress. PATOGENESIS 3. Gangguan fungsi sensoris Pada NUD : “decreased sensory threshold”. Lesi organik sistem syaraf afferent visceral. 4. Kejiwaan Tak ada hubungan dengan kepribadian. Stress yang berlangsung lama. PATOGENESIS 5. Post infeksi kuman Helicobacter pylori 40-80% pasien dispepsia : kuman H. pylori (+). Tidak semua Hp (+), dispepsia (+). Chronic inflammation visceral hyperalgesia. 6. Duodenitis 14-83% pasien dispepsia : PA (+) duodenitis. Tidak semua End (+), PA (+) gastro-duodenitis. Kelainan PA tidak selalu = keluhan. PATOGENESIS 7. Diet dan lingkungan Dispepsia akut : pemakai aspirin, NSAID. Dispepsia juga (+) : rokok, kopi. 50% berhubungan dengan makanan : fatty, kopi, merokok, alkohol, pedas, asam, panas, soda, dll. KLASIFIKASI DISPEPSIA (Roma II – 1999) 1. Tipe ulkus (“ulcer like”) 2. Tipe dismotilitas (“dysmotility like”) 3. Tipe tidak spesifik (“unspecified”) Klasifikasi dispepsia berdasarkan keluhan yang dominan ini sebenarnya kurang berarti dalam klinik, karena masingmasing saling tumpang tindih. Namun mungkin berguna untuk pilihan pengobatan bagi pasien. Kriteria Diagnostik Roma III DISPEPSIA FUNGSIONAL Paling sedikit 3 bulan, dengan serangan minimal selama 6 bulan sebelumnya, salah satu atau lebih keluhan berikut ini : - Rasa penuh yang mengganggu sehabis makan. - Cepat kenyang. - Nyeri epigastrium. - Rasa terbakar di epigastrium dan Tidak ada bukti adanya kelainan struktur atau anatomi (termasuk pemeriksaan gastroskopi) yang dapat menjelaskan keluhan tersebut. DIAGNOSIS 1. Anamnesis : sangat penting. 2. Pemeriksaan fisik : tak banyak membantu. 3. Laboratorium : kuman Helicobacter pylori. 4. Foto Barium Saluran Cerna Atas (UGI). 5. Endoskopi : menyingkirkan kelainan organik. Alarms atau ‘Red Flags’ dimana Endoskopi sebaiknya segera dikerjakan pada dispepsia 1. Anemia 2. Perdarahan gastrointestinal 3. Sering muntah 4. Anoreksia dengan BB menurun 5. Teraba masa atau benjolan 6. Upper GI photo menunjukkan kelainan yang mencurigakan. DIAGNOSIS BANDING 1. Penyakit refluks gastro-esofageal (GERD). 2. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). 3. Penyakit saluran empedu (batu). 4. Pankreatitis kronik. 5. Dispepsia karena obat 6. Kelainan jiwa. 7. Lain-lain. PENGOBATAN DISPEPSIA 70% pasien membaik dengan plasebo, mudah kambuh, kadangkadang membangkang. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Penghambat asam : - Penyekat reseptor H-2 (PRH-2). - Penyekat pompa proton (PPP). Antibiotika/anti H. pylori. Prokinetik : metoklopramide, domperidon, cisapride. Antimuntah : antihistamin, fenotiasin, ondansetron. Sitoprotektor : bismuth, sukralfat, setraksat. Anti-depresan ringan : tricyclic. Antasida. Antispasmodik/antikolinergik. HELICOBACTER PYLORI Bizzozero, 1893 : kuman spiral dalam lambung mamalia. Waren & Marshal, 1983 : Campylobacter-like organism dalam lambung penderita gastritis kronik & tukak peptik. Goddwin dkk., 1989 : Helicobacter pylori. Kuman gram negatif, bulat lonjong, spiral, flagela. Hidup antara lapisan mukus dan epitel lambung. Hanya berkoloni di sel epitel lambung, terutama korpus dan antrum. Helicobacter pylori HELICOBACTER PYLORI Epidemiologi Prevalensi lebih tinggi di : Negara berkembang. Sosio-ekonomi rendah. Lingkungan berjubel semasa anak. Ras/etnik dan genetik tertentu. Pada penyakit saluran makan : Tukak duodenum : 95 – 100% Gastritis kronik : 90 – 95% Tukak lambung : 85 – 90% Dispepsia non tukak : 7 – 72% HELICOBACTER PYLORI (HP) 1. Efek sitotoksik : merusak mukosa lambung. 2. Respons imunologik, mukosa. 3. Reaksi inflamasi kronik. menekan resistensi Suerbaum & Micheti, NEJM 2002;347:1175-1186 HELICOBACTER PYLORI Memegang peranan penting dalam patogenesis beberapa penyakit: Gastritis akut, Gastritis kronik atrofikans, Penyakit tukak peptik, Metaplasia intestinal, Kanker lambung, dan “Mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma”. HELICOBACTER PYLORI (HP) In 1994 “IARC (the International Agency for Research on Cancer)” – a working party of the WHO – designated H. (“definitive”) carcinogen. pylori as class 1 Urea breath test Pasien diberi pil berisi urea dengan atom karbon yang diberi label 14C& 13C Bila ada H.pylori, maka akan ditemukan CO2 dengan label 13 atau 14 pada saat pasien bernafas Pemeriksaan H.pylori Maastricht 3–2006 • Uji imunologi / serologi Digunakan secara luas, uji non-invasif yang tidak mahal Akurasi diagnostik rendah (80-84%) Disarankan untuk evaluasi ke arah infeksi H.pylori pada pasien dengan ulkus yang berdarah dan keadaan yang berkaitan dengan densitas bakteri yang rendah Invasif • Endoskopi dengan biopsi lambung untuk uji urease cepat (rapid urease test) Malfertheiner P et al. Gut 2007;56:772-781 Colony of H pylori in anthral gland PENGOBATAN Anti Helicobacter pylori : 1. Monotherapy : ARH-2 atau PPP. 2. Dual therapy : ARH-2/PPP+ampicillin/ clarithromycin. 3. Triple therapy : PPP+ampicillin+clarithromycin/ metronidazole. 4. Quadruple therapy : PPP+clarithromycin+metronidazol +bismuth PENGOBATAN Pengobatan sangat dianjurkan pada : Tukak duodenum/tukak lambung (baik aktif atau tidak, termasuk tukak peptik dengan komplikasi). MALT Lymphoma (Limfoma “Mucosal Associated Lymphoid Tissues”) Gastritis atrofikans. Pasca reseksi kanker lambung. Pasien yang mempunyai saudara kandung atau orang tua kandung dengan kanker lambung. Keinginan pasien sendiri (setelah diberi penjelasan selengkapnya oleh dokter). TUKAK PEPTIK BATASAN Tukak peptik adalah kerusakan jaringan mulai dari mukosa, submukosa, sampai dengan muskularis mukosa dari saluran makan bagian atas, dengan batas yang jelas, akibat pengaruh asam lambung dan pepsin. TUKAK PEPTIK PATOFISIOLOGI Patofisiologi terjadinya tukak peptik sangat kompleks. Asam bukan satu-satunya faktor penyebab, masih banyak faktor lain. Penting adanya keseimbangan antara : Faktor agresif asam-pepsin dengan Faktor defensif mukosa lambung dan usus. HCL Pepsin pH 2.0 Mucus pH 7.0 HCO3 pH 7.0 H+ Sensory nerve 7 Mucus HCO3 HCO3 3 M Muscularis Mucosa Mucus Bicarbonat Mucosal cell renewal 5 Microvessels 2 Surface epithelial cells 1 6 4 “Alkaline tide” Prostaglandin E2 & prostacyclin H+ M M Submucosal Artery Submucosal Vein Nerve Figure . Mucosal defence mechanisms* Tarnawski A, Eerickson R: Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1991. TUKAK PEPTIK PATOFISIOLOGI Pertahanan mukosa menurun bila timbul : Kerusakan mukosa Penurunan sekresi mukus Penurunan sekresi bikarbonat Penurunan aliran darah mukosa (mikrosirkulasi) Agresivitas asam lambung ditentukan oleh : Sekresi asam malam hari (nocturnal secretion) pH intraluminer yang tetap rendah Pembersihan asam dalam lambung Pathogenesis of gastric mucosal injuri NO ULCER DEFENSIVE FACTORS: Mucous membrane barrier Mucus Bicarbonante ion Blood flow in gastric mucosa Proliferating factors Prostaglandin in gastric mucosa ULCER Inflammation (Response to cell injury) Gastric acid (Terano A , 2001) TUKAK PEPTIK PATOFISIOLOGI Tukak lambung faktor defensif Tukak duodenum faktor agresif TUKAK PEPTIK DIAGNOSIS 1. Anamnesis : sangat penting untuk diagnosis, tak selalu spesifik, datang dengan komplikasi dispepsia kronik, nyeri epigastrium (“Rhythmicity” : hunger pain food relieve, “Chronicity” : sudah lama, “Periodicity” : malam hari) 2. Pemeriksaan fisik : tak banyak membantu. 3. Laboratorium : kuman H. pylori. 4. Foto barium SCBA (saluran cerna bagian atas). 5. Endoskopi + biopsi. TUKAK PEPTIK KOMPLIKASI 1. Perdarahan : hematemesis – melena 2. Perforasi lambung 3. Striktur pilorus TUKAK PEPTIK PENGOBATAN Tujuan pengobatan : 1. Menghilangkan keluhan. 2. Menyembuhkan tukak. 3. Mencegah kekambuhan & komplikasi. TUKAK PEPTIK PENGOBATAN 1. Diet (diet ketat tak dianjurkan lagi, hindari makanan yg memperberat keluhan asam, pedas, panas, banyak lemak, khususnya makan teratur dan hindarkan makan sebelum tidur). 2. Stop merokok. 3. Hindari alkohol terutama dalam lambung kosong. 4. Hindari ASA/NSAID/Steroid. 5. Banyak istirahat, hindari stress. 6. Obat anti tukak. TUKAK PEPTIK PENGOBATAN Obat anti tukak : 1. Penghambat sekresi asam lambung. 2. Sitoprotektif. 3. Prokinetik. 4. Anti H. Pylori. TUKAK PEPTIK Pengobatan : 1. Penghambat sekresi asam : 1.1. Antagonist reseptor H-2 (ARH-2) : -Cimetidine -Famotidine -Nizatidine -Ranitidine -Roxatidine 1.2. Antikholinergik : -Atropine -Propantheline bromide -Gastrozepine 1.3. Penyekat pompa proton (PPP) -Omeprazole -Pantoprazole -Esomeprazole -Lansoprozole -Rabeprazole TUKAK PEPTIK Pengobatan : 2. Obat sitoprotektif : 2.1. Prostaglandin sintetik -Misoprostol 2.2. Koloidal bismuth 2.3. Sucralphate 2.4. Cetraxate 2.5. Treprenone 2.6. Rebamipide -Enprostil TUKAK PEPTIK Pengobatan : 3. Obat prokinetik : 1. Domperidon 2. Metoclopramide 3. Clebopride 4. Cisapride. TUKAK PEPTIK Pengobatan : 4. Anti Helicobacter pylori : 1. Monotherapy : ARH-2 atau PPP. 2. Dual therapy : ARH-2/PPP+ampicillin/ clarithromycin. 3. Triple therapy : PPP+ampicillin+clarithromycin/ metronidazole. 4. Quadruple therapy : PPP+clarithromycin+metronidazol +bismuth PENYAKIT REFLUKS GASTROESOFAGEAL (GERD) Kelainan patologi yang disebabkan oleh usaha untuk mengeluarkan isi lambung ke dalam esofagus, yang dapat menyangkut kelainan (keluhan maupun gejala) dari esofagus, farings, larings, maupun saluran nafas. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Pathophysiology of GERD Impaired mucosal defence peristaltic salivary HCO3 esophageal clearance of acid (lying flat, alcohol, coffee) Impaired LES – transient LES relaxations (TLESR) – hypotensive LES acid output (smoking, coffee) H. pylori H+ Hiatus hernia Bile and pancreatic enzymes Pepsin intragastric pressure (obesity, lying flat) gastric emptying (fat) bile reflux de Caestecker, BMJ 2001; 323:736–9. Johanson, Am J Med 2000; 108(Suppl 4A): S99–103. PENYAKIT REFLUKS GASTROESOFAGEAL (GERD) KLINIK : 1. Keluhan khas (“typical”) : Nyeri epigastrium (perih atau rasa panas), menjalar ke atas, ke arah retrosternal dan leher (“heartburn”), regurgitasi asam (rasa asam di mulut), sekresi ludah berlebihan, hematemesis. 2. Tidak khas (“atypical”) : disfagia, nyeri dada (“chestpain”), nyeri telan. 3. Ekstra-esofagus : Batuk-batuk lama, suara parau, sesak nafas. PENYAKIT REFLUKS GASTROESOFAGEAL (GERD) TIGA SPEKTRUM PENYAKIT : 1. NERD (Non Erosive Reflux Disease) : “Heartburn”, regurgitasi asam, tak ada kelainan esofagus pada pemeriksaan endoskopi. 2. GERD (Gastro Esophageal Reflux Disease) : Keluhan “heartburn”, regurgitasi asam, esofagitis derajat ringan sampai berat pada endoskopi. 3. Esofagus BARET : Kelainan khas pada pemeriksaan endoskopi. PENYAKIT REFLUKS GASTROESOFAGEAL (GERD) DIAGNOSIS : 1. Gambaran klinik 2. Acid suppresion test (PPP test) 3. Tes perfusi Bernstein 4. Endoskopi : esofagitis 5. Monitoring pH esofagus selama 24 jam 6. Manometri PENYAKIT REFLUKS GASTROESOFAGEAL (GERD) Tergantung spektrum penyakit A. NERD : berjalan jinak, tak memberi komplikasi serius. B. ESOFAGUS “BARET” : adeno-carcinoma esofagus. C. GERD : 1. Tukak esofagus 2. Striktur esofagus 3. Perdarahan SMBA PENYAKIT REFLUKS GASTROESOFAGEAL (GERD) PENGOBATAN : A. Umum Turunkan BB, tidur ½ duduk, tunggu perut kosong. Hindari rokok, kopi, coklat, alkohol, pedas, lemak. Pakaian longgar. Hindari obat tertentu : theofilin, caffein, dst. B. Khusus PPP, prokinetik, sitoprotektif, antasida. Bedah bila obat gagal. GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT BLEEDING Gastrointestinal tract bleeding divided into two groups : 1. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding 2. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding How to differentiate ??? the source of bleeding 1. Upper GI bleeding : Upper GI bleeding originates in the first part of the GI tract-the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum (first part of the intestine). 2. Lower GI bleeding : Lower GI bleeding originates in the portions of the GI tract farther down the digestive system-the segment of the small intestine farther from the stomach, large intestine, rectum, and anus. Upper GI Bleeding The major causes of UGIB are duodenal ulcer hemorrhage (25%), gastric ulcer hemorrhage (20%), mucosal tears of the esophagus or fundus (Mallory-Weiss tear), esophageal varices, erosive gastritis, erosive esophagitis, Dieulafoy lesion, gastric varices, gastric cancer, and ulcerated gastric leiomyoma. Rare causes of UGIB include aortoenteric fistula, gastric antral vascular ectasia, angiectasias, and Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. Lower GI Bleeding Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) accounts for 2033% of episodes of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. LGIB that requires hospitalization represents less than 1% of all hospital admissions in the United States. The leading causes of significant LGIB are diverticulosis and angiodysplasia. Diverticulosis accounts for 30-50% of the cases of hemodynamically significant LGIB, while angiodysplasia accounts for 20-30% of cases. Some experts believe that angiodysplasia is the most frequent cause of LGIB in patients older than 65 years. Hemorrhoids are the most common cause of LGIB in patients younger than 50 years, but bleeding is usually minor and is rarely the cause of significant LGIB. According to a review of 7 series of patients with LGIB, the most common cause of LGIB was diverticulosis, accounting for 33% of cases, followed by cancer and polyps, which accounted for 19% of cases. Common causes of LGIB include diverticular bleeding, angiodysplasia, ischemic colitis, radiation-induced colitis, and other vascular causes. Neoplasms, infectious colitis, idiopathic colitis, anorectal abnormalities, as well as other entities can also cause LGIB. Diagnostic Approach History and physical examination Focused history to identify risk factors (e.g., NSAID or alcohol use) and to evaluate likely source of bleeding Physical examination Evaluate hemodynamic stability by measurement of heart rate and blood pressure. Search for signs of an underlying disorder (e.g., liver disease). Rectal examination is usually indicated; consider anoscopy if appropriate. Laboratory evaluation Degree of anemia Diagnostic procedures Upper endoscopy in patients with suspected upper GI bleeding Colonoscopy in patients with suspected lower GI bleeding Other imaging studies, when indicated Diagnosis of Upper GI Bleeding Imaging Studies Chest radiographs should be ordered to exclude aspiration pneumonia, effusion, and esophageal perforation; abdominal scout and upright films should be ordered to exclude perforated viscus and ileus. Barium contrast studies are not usually helpful and can make endoscopic procedures more difficult (ie, white barium obscuring the view) and dangerous (ie, risk of aspiration). CT scan and ultrasonography may be indicated to evaluate liver disease with cirrhosis, cholecystitis with hemorrhage, pancreatitis with pseudocyst and hemorrhage, aortoenteric fistula, and other unusual causes of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Nuclear medicine scans may be useful to determine the area of active hemorrhage. Angiography may be useful if bleeding persists and endoscopy fails to identify a bleeding site. As salvage therapy, embolization of the bleeding vessel can be as successful as emergent surgery in patients who have failed a second attempt of endoscopic therapy. Diagnosis of Lower GI Bleeding Diagnosis for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, it is colonoscopy, or arteriography if the bleeding is too brisk. When bleeding cannot be identified and controlled, intraoperative enteroscopy or arteriography may help localize the bleeding source, facilitating segmental resection of the bowel. If no upper gastrointestinal or large bowel source of bleeding is identified, the small bowel can be investigated using a barium-contrast upper gastrointestinal series with small bowel follow-through, enteroclysis, push enteroscopy, technetium-99mtagged red blood cell scan, arteriography, or a Meckel's scan. These tests may be used alone or in combination. PENATALASANAAN AWAL Anannesis & pemeriksaan fisis Tanda vital, Jalan infus yg sangat besar Selang nasogastrik Hb, Ht, trombosit, hemostaisis Hemodinamik stabil Tidak ada perdarahan aktif Hemodinamik tidak stabil Perdarahan aktif Pengobatan empirik RESUSITASI Cairan krostaloid, cairan koloid, Transfusi darah, koreksi faktor koagulasi Hemodinamik stabil Perdarahan berhenti Hemodinamik stabil Perdarahan tetap berlangsung Perdarahan berhenti Elektif Endoskopi SCBA Emergensi atau Dini Endoskopi SCBA Varises esophagus lambung Pengobatan definitif Obat Vasoaktif Octreotide, Somat ostatin, Vasopressin Bedah Jika gagal Skleroterapi Atau ligasi Atau “SB tube” Tukak Injeksi, hemostatik Atau bedah segera Sumber perdarahan Tak tervisualisasi Radiologi, Intervensional Diagnostik & terapeutik Atau bedah segera INITIAL ASSESSMENT History & Physical Exam;vital sign; large bore iv line;nasogastric tube;laboratory examtasis;Hb, Ht, thrombocyte,hemostasis Hemodynamic stable; No active bleeding Hemodynamic instable; Active bleeding Emperical treatment RESUSCITATION Crystalloid solution; Colloid solution Blood Transfusion; Correction for coagulation factors Hemodynamic stable; Bleeding stop Hemodynamic instable; Bleeding continued Bleeding stop EMERGENCY or EARLY UGI endoscopy ELECTIVE UGI endoscopy Esophageal/gastric Varices Sclerotherapy or Ligattion Or SB tube Ulcer Hemostatic injection Or urgent surgery VASOACTIVE DRUGS Ocreotide; Somatostatin vasopressin Bleeding site non-visualized Interventional diagnostic & therapeutic radiology or urgent surgery If fail DEFINITIVE TREATMT Surgery Algoritma penatalaksanaan perdarahan varises di Rumah Sakit Tipe A dan B, dimama tersedia fasilitas endoskopi. INITIAL ASSESSMENT History & Physical Exam; Vital sign; Large bore iv line;nasogastric tube;laboratory examtasis;Hb, Ht, thrombocyte,hemostasis Hemodynamic stable; No active bleeding Emperical treatment Vit.K;Antisecretory Drugs;Antacida;Sucralfate Hemodynamic stable; Bleeding stop BP.90/60 mmHg;pulse,100/m; Hb>9g%;Tilt test (-) Referral system for Elective Evaluation UGI Barium Radiography or Referal for Upper GI Endoscopy DEFINITIVE TREATMT Hemodynamic instable; Active bleeding RESUSCITATION Crystalloid solution;Colloid solution; Transfusion: PRC +/- FFP Hemodynamic instable; Bleeding BP<90/60 mmH;Pulse>100/m; Hb<9g%;Tilt test (+) STABILIZATION Fluid resuscitation; blood Transfusion; Coagulation factors REFERRAL in Stable hemodynamic VASO-ACTIVE DRUG Octreotide;Somatostatin vasopressin Resuscitation a. Mild or Moderate Bleed * Pulse and blood pressure : N * Hb > 10 mg/ml * Without comorbidity * Less than 60 years of age b. Severe Bleed Pulse > 100 beats/min Sistolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg Hb < 10 mg/ml Aged > 60 years Table 1. Hypovolaemic shock: symptoms, sign, and fluid replacement Blood loss (ml) Blood loss (%bv) Pulse rate Blood pressure Pulse pressure Respiratory rate Urine output Mental status Fluid replacement <750 <15% <100 Norma Normal or increased 14-20 >30 Slightly anxious Crystalloid 750-1500 15-30% >100 Norma Decreased 20-30 20-30 Mildly anxious Crystalloid 1500-2000 30-40% >120 Decreased Decreased 30-40 30-40 Anxious & confused Crystalloid & blood >2000 <40% >140 Decreased Decreased >35 >35 Confused & letargic Crystalloid blood Adapted from Grenvick A, Ayres SM, Holbrook PR, et al. Textbook of critical care. 4th edition. Philadelphia WB Saunders Company; 40-5 DIARRHEA Diarrhea is a common symptom that can range in severity from an acute, self-limited annoyance to a severe, life-threatening illness. Patients may use the term "diarrhea" to refer to increased frequency of bowel movements, increased stool liquidity, a sense of fecal urgency, or fecal incontinence Definition • In the normal state, approximately 10 L of fluid enter the duodenum daily, of which all but 1.5 L are absorbed by the small intestine. The colon absorbs most of the remaining fluid, with only 100 mL lost in the stool. From a medical standpoint, diarrhea is defined as a stool weight of more than 250 g/24 h • The causes of diarrhea are myriad. In clinical practice, it is helpful to distinguish acute from chronic diarrhea, as the evaluation and treatment are entirely different Causes of acute infectious diarrhea • 1. 2. 3. Noninflammatory Diarrhea Viral - Norwalk virus, Norwalk-like virus, Rotavirus Protozoal - Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium Bacterial - Preformed enterotoxin production Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens Enterotoxin production; Enterotoxigenic E coli (ETEC), Vibrio cholerae Inflammatory Diarrhea • Viral – Cytomegalovirus • Protozoal - Entamoeba histolytica • Bacterial - Cytotoxin productio; Enterohemorrhagic E coli, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Clostridium difficile. Mucosal invasion; Shigella, Campylobacter jejuni Salmonella, Enteroinvasive E coli ,Aeromonas Plesiomonas,Yersinia enterocolitica,Chlamydia Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Listeria monocytogenes Causes of chronic diarrhea • Osmotic diarrhea Stool volume decreases with fasting; increased stool osmotic gap 1. Medications: antacids, lactulose, sorbitol 2. Disaccharidase deficiency: lactose intolerance 3. Factitious diarrhea: magnesium (antacids, laxatives) CLUES: Secretory diarrhea • Large volume ( >1 L/d); little change with fasting; normal stool osmotic gap 1. Hormonally mediated: VIPoma, carcinoid, medullary carcinoma of thyroid (calcitonin), Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrin) 2. Factitious diarrhea (laxative abuse): phenolphthalein, cascara, senna 3. Villous adenoma 4. Bile salt malabsorption (ileal resection; Crohn's ileitis; postcholecystectomy) 5. Medications Inflammatory conditions • Fever, hematochezia, abdominal pain 1. Ulcerative colitis 2. Crohn's disease 3. Microscopic colitis 4. Malignancy: lymphoma, adenocarcinoma (with obstruction and pseudodiarrhea) 5. Radiation enteritis Malabsorption syndromes • Weight loss, abnormal laboratory values; fecal fat > 7-10 g/24 h, tropical sprue, Whipple's disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Crohn's disease, small bowel resection (short bowel syndrome) 2. Lymphatic obstruction: lymphoma, carcinoid, infectious (TB, MAI), Kaposi's sarcoma, sarcoidosis, retroperitoneal fibrosis 3. Pancreatic disease: chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma 4. Bacterial overgrowth: motility disorders (diabetes, vagotomy, scleroderma), fistulas, small intestinal diverticula Motility disorders • Systemic disease or prior abdominal surgery 1. Postsurgical: vagotomy, partial gastrectomy, blind loop with bacterial overgrowth 2. Systemic disorders: scleroderma, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism 3. Irritable bowel syndrome Chronic infections • Parasites: Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, Cyclospora • AIDS-related: • Viral: Cytomegalovirus, HIV infection (?) • Bacterial: Clostridium difficile, Mycobacterium avium complex • Protozoal: Microsporida (Enterocytozoon bieneusi ), Cryptosporidium, Isospora belli ACUTE DIARRHEA • Diarrhea that is acute in onset and persists for less than 3 weeks is most commonly caused by infectious agents, bacterial toxins (either ingested preformed in food or produced in the gut), or drugs • Recent ingestion of improperly stored or prepared food implicates food poisoning, especially if other people were similarly affected. Exposure to unpurified water (camping, swimming) may result in infection with Giardia or Cryptosporidium TRAVELER'S DIARRHEA • Whenever a person travels from one country to another—particularly if the change involves a marked difference in climate, social conditions, or sanitation standards and facilities—diarrhea is likely to develop within 2–10 days • There may be up to ten or even more loose stools per day, often accompanied by abdominal cramps, nausea, occasionally vomiting, and rarely fever. The stools do not usually contain mucus or blood, and aside from weakness, dehydration, and occasionally acidosis, there are no systemic manifestations of infection. The illness usually subsides spontaneously within 1–5 days, although 10% remain symptomatic for a week or longer, and in 2% symptoms persist for longer than a month • Bacteria cause 80% of cases of traveler's diarrhea, with enterotoxigenic E coli, Shigella species, and Campylobacter jejuni being the most common pathogens. Less common causative agents include Aeromonas, Salmonella, noncholera vibrios, Entamoeba histolytica, and Giardia lamblia. Contributory causes may at times include unusual food and drink, change in living habits, occasional viral infections (adenoviruses or rotaviruses), and change in bowel flora • For most individuals, the affliction is short-lived, and symptomatic therapy with opiates or diphenoxylate with atropine is all that is required provided the patient is not systemically ill (fever ł 39 °C) and does not have dysentery (bloody stools), in which case antimotility agents should be avoided. Packages of oral rehydration salts to treat dehydration are available over the counter in the USA and in many foreign countries • Avoidance of fresh foods and water sources that are likely to be contaminated is recommended for travelers to developing countries, where infectious diarrheal illnesses are endemic. Prophylaxis is recommended for those with significant underlying disease (inflammatory bowel disease, AIDS, diabetes, heart disease in the elderly • Prophylaxis is started upon entry into the destination country and is continued for 1 or 2 days after leaving. For stays of more than 3 weeks, prophylaxis is not recommended because of the cost and increased toxicity. For prophylaxis, bismuth subsalicylate is effective but turns the tongue and the stools blue and can interfere with doxycycline absorption, which may be needed for malaria prophylaxis. Numerous antimicrobial regimens for oncedaily prophylaxis also are effective, such as norfloxacin 400 mg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg, ofloxacin 300 mg, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg. daily for 5 days • Because not all travelers will have diarrhea and because most episodes are brief and self-limited, an alternative approach that is currently recommended is to provide the traveler with a 3- to 5-day supply of antimicrobials to be taken if significant diarrhea occurs during the trip. Commonly used regimens include ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily, ofloxacin 300 mg twice daily, or norfloxacin 400 mg twice daily. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg twice daily can be used as an alternative (especially in children), but resistance is common in many areas. Aztreonam, a poorly absorbed monobactam with activity against most bacterial enteropathogens, also is efficacious when given orally in a dose of 100 mg three times Noninflammatory Diarrhea • Watery, nonbloody diarrhea associated with periumbilical cramps, bloating, nausea, or vomiting (singly or in any combination) suggests small bowel enteritis caused by either a toxinproducing bacterium (enterotoxigenic E coli [ETEC], Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, C perfringens) or other agents (viruses, Giardia) that disrupt the normal absorption and secretory process in the small intestine. • Prominent vomiting suggests viral enteritis or S aureus food poisoning. Though typically mild, the diarrhea (which originates in the small intestine) may be voluminous (ranging from 10 to 200 mL/kg/24 h) and result in dehydration with hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis due to loss of HCO3– in the stool (eg, cholera). Because tissue invasion does not occur, fecal leukocytes are not present. Inflammatory Diarrhea • The presence of fever and bloody diarrhea (dysentery) indicates colonic tissue damage caused by invasion (shigellosis, salmonellosis, Campylobacter or Yersinia infection, amebiasis) or a toxin (C difficile, E coli O157:H7). Because these organisms involve predominantly the colon, the diarrhea is small in volume (< 1 L/d) and associated with left lower quadrant cramps, urgency, and tenesmus. • Fecal leukocytes are present in infections with invasive organisms. E coli O157:H7 is a toxigenic, noninvasive organisms that may be acquired from contaminated meat or unpasteurized juice and has resulted in several outbreaks of an acute, often severe hemorrhagic colitis. In immunocompromised and HIV-infected patients, cytomegalovirus may result in intestinal ulceration with watery or bloody diarrhea Enteric Fever • A severe systemic illness manifested initially by prolonged high fevers, prostration, confusion, respiratory symptoms followed by abdominal tenderness, diarrhea, and a rash is due to infection with Salmonella typhi or Salmonella paratyphi, which causes bacteremia and multiorgan dysfunction Evaluation • In over 90% of patients with acute diarrhea, the illness is mild and self-limited and responds within 5 days to simple rehydration therapy or antidiarrheal agents • Patients with signs of inflammatory diarrhea manifested by any of the following require prompt medical attention: high fever (> 38.5 °C), bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, or diarrhea not subsiding after 4–5 days. Similarly, patients with symptoms of dehydration must be evaluated (excessive thirst, dry mouth, decreased urination, weakness, lethargy) • Physical examination should note the patient's general appearance, mental status, volume status, and the presence of abdominal tenderness or peritonitis • Peritoneal findings may be present in C difficile and enterohemorrhagic E coli. Hospitalization is required in patients with severe dehydration, toxicity, or marked abdominal pain. Stool specimens should be sent in all cases for examination for fecal leukocytes and bacterial cultures • The rate of positive bacterial cultures in patients with dysentery is 60–75%. A wet mount examination of the stool for amebiasis should also be performed in patients with dysentery who have a history of recent travel to endemic areas or those who are homosexuals. In patients with a history of antibiotic exposure, a stool sample should be sent for C difficile toxin. If E coli O157:H7 is suspected, the laboratory must be alerted to do specific serotyping. In patients with diarrhea that persists for more than 10 days, three stool examinations for ova and parasites also should be performed. Rectal swabs may be sent for Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and herpes simplex virus in sexually active patients with severe proctitis Treatment • Diet :The overwhelming majority of adults have mild diarrhea that will not lead to dehydration provided the patient takes adequate oral fluids containing carbohydrates and electrolytes. Patients will find it more comfortable to rest the bowel by avoiding high-fiber foods, fats, milk products, caffeine, and alcohol. Frequent feedings of fruit drinks, tea, "flat" carbonated beverages, and soft, easily digested foods (eg, soups, crackers) are encouraged Rehydration • In more severe diarrhea, dehydration can occur quickly, especially in children. Oral rehydration with fluids containing glucose, Na+, K+, Cl–, and bicarbonate or citrate is preferred in most cases to intravenous fluids because it is inexpensive, safe, and highly effective in almost all awake patients • An easy mixture is ˝ tsp salt (3.5 g), 1 tsp baking soda (2.5 g NaHCO3), 8 tsp sugar (40 g), and 8 oz orange juice (1.5 g KCl), diluted to 1 L with water. Alternatively, oral electrolyte solutions (eg, Pedialyte) are readily available. Fluids should be given at rates of 50–200 mL/kg/24 h depending on the hydration status. Intravenous fluids (lactated Ringer's solution) are preferred acutely in patients with severe dehydration. Antidiarrheal Agents • Loperamide is the preferred drug in a dosage of 4 mg initially, followed by 2 mg after each loose stool (maximum:16 mg/24 h • Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol), two tablets or 30 mL four times daily, reduces symptoms in patients with traveler's diarrhea by virtue of its antiinflammatory and antibacterial properties • Anticholinergic agents are contraindicated in acute diarrhea Antibiotic Therapy • Empiric treatment-fluoroquinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily) for 5–7 days. These agents provide good antibiotic coverage against most invasive bacterial pathogens, including Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, and Aeromonas. Alternative agents are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 160/800 mg twice daily, or erythromycin, 250–500 mg four times daily • Specific antimicrobial treatment- Antibiotics are not generally recommended in patients with nontyphoid Salmonella, Campylobacter, or Yersinia infection except in severe or prolonged disease because they have not been shown to hasten recovery or reduce the period of fecal bacterial excretion. The infectious diarrheas for which treatment is clearly recommended are shigellosis, cholera, extraintestinal salmonellosis, "traveler's" diarrhea, C difficile infection, giardiasis, amebiasis, and the sexually transmitted infections (gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydiosis, and herpes simplex infection) CHRONIC DIARRHEA • Etiology The causes of chronic diarrhea may be grouped into six major pathophysiologic categories Osmotic Diarrheas • As stool leaves the colon, fecal osmolality is equal to the serum osmolality, ie, approximately 290 mosm/kg. Under normal circumstances, the major osmoles are Na+, K+, Cl–, and HCO3–. The stool osmolality may be estimated by multiplying the stool (Na+ + K+) × 2 (multiplied by 2 to account for the anions) • The osmotic gap is the difference between the measured osmolality of the stool (or serum) and the estimated stool osmolality and is normally less than 50 mosm/kg • An increased osmotic gap implies that the diarrhea is caused by ingestion or malabsorption of an osmotically active substance • The most common causes of osmotic diarrhea are disaccharidase deficiency (lactase deficiency), laxative abuse, and malabsorption syndromes (see below). Osmotic diarrheas resolve during fasting. Osmotic diarrheas caused by malabsorbed carbohydrates are characterized by abdominal distention, bloating, and flatulence due to increased colonic gas production. Malabsorptive Conditions • The major causes of malabsorption are small mucosal intestinal diseases, intestinal resections, lymphatic obstruction, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and pancreatic insufficiency • In patients with suspected malabsorption, quantification of fecal fat should be performed Secretory Conditions • Increased intestinal secretion or decreased absorption results in a watery diarrhea that may be large in volume (1–10 L/d) but with a normal osmotic gap • here is little change in stool output during the fasting state. In serious conditions, significant dehydration and electrolyte imbalance may develop. Major causes include endocrine tumors (stimulating intestinal or pancreatic secretion), bile salt malabsorption (stimulating colonic secretion), and laxative abuse Inflammatory Conditions • Diarrhea is present in most patients with inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, microscopic colitis). A variety of other symptoms may be present, including abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, and hematochezia Motility Disorders • Abnormal intestinal motility secondary to systemic disorders or surgery may result in diarrhea due to rapid transit or to stasis of intestinal contents with bacterial overgrowth resulting in malabsorption Chronic Infections • Chronic parasitic infections may cause diarrhea through a number of mechanisms. Although the list of parasitic organisms is a long one, agents most commonly associated with diarrhea include the protozoans Giardia, E histolytica, Cyclospora, and the intestinal nematodes • Immunocompromised patients, especially those with AIDS, are susceptible to a number of infectious agents that can cause acute or chronic diarrhea Chronic diarrhea in AIDS is commonly caused by Microsporida, Cryptosporidium, cytomegalovirus, Isospora belli, Cyclospora, and Mycobacterium avium complex. Factitial Diarrhea • Approximately 15% of patients with chronic diarrhea have factitial diarrhea caused by surreptitious laxative abuse or factitious dilution of stool Evaluation • Stool Analysis - Twenty-four-hour stool collection for weight and quantitative fecal fat–A stool weight of more than 300 g/24 h confirms the presence of diarrhea, justifying further workup. A weight greater than 1000–1500 g suggests a secretory process. A fecal fat in excess of 10 g/24 h indicates a malabsorptive process • 2. Stool osmolality–An osmotic gap confirms osmotic diarrhea. A stool osmolality less than the serum osmolality implies that water or urine has been added to the specimen (factitious diarrhea). • 3. Stool laxative screen–In cases of suspected laxative abuse, stool magnesium, phosphate, and sulfate levels may be measured. Phenolphthalein, senna, and cascara are indicated by the presence of a bright-red color after alkalinization of the stool or urine. Bisacodyl can be detected in the urine 4. Fecal leukocytes–The presence of leukocytes in a stool sample implies an underlying inflammatory diarrhea. • 5. Stool for ova and parasites–The presence of Giardia and E histolytica is detected in routine wet mounts. Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora are detected with modified acidfast staining. Blood Tests • Routine laboratory tests–CBC, serum electrolytes, liver function tests, calcium, phosphorus, albumin, TSH, total T4, beta-carotene, and prothrombin time should be obtained. Anemia occurs in malabsorption syndromes (vitamin B12, folate, iron) and inflammatory conditions. Hypoalbuminemia is present in malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathies, and inflammatory diseases. Hyponatremia and non–anion gap metabolic acidosis may occur in profound secretory diarrheas. Malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins may result in an abnormal prothrombin time, low serum calcium, low carotene, or abnormal serum alkaline phosphatase Other laboratory tests • In patients with suspected secretory diarrhea, serum VIP (VIPoma), gastrin (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), calcitonin (medullary thyroid carcinoma), cortisol (Addison's disease), and urinary 5-HIAA (carcinoid syndrome) levels should be obtained • Proctosigmoidoscopy With Mucosal Biopsy: Examination may be helpful in detecting inflammatory bowel disease (including microscopic colitis) and melanosis coli, indicative of chronic use of anthraquinone laxatives. Imaging • Calcification on a plain abdominal radiograph confirms the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. An upper gastrointestinal series or enteroclysis study is helpful in evaluating Crohn's disease, lymphoma, or carcinoid syndrome. Colonoscopy is helpful in evaluating colonic inflammation due to inflammatory bowel disease. Upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsy is useful in suspected malabsorption due to mucosal diseases. Upper endoscopy with a duodenal aspirate and small bowel biopsy is also useful in patients with AIDS and to document Cryptosporidium, Microsporida, and M aviumintracellulare infection. Abdominal CT is helpful to detect chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic endocrine tumors. Treatment • A. Loperamide: 4 mg initially, then 2 mg after each loose stool (maximum: 16 mg/d) • Diphenoxylate With Atropine: One tablet three or four times daily • Codeine, Paregoric: Because of their addictive potential, these drugs are generally avoided except in cases of chronic, intractable diarrhea. Codeine may be given in a dosage of 15–60 mg every 4 hours as needed; the dosage of paregoric is 4–8 mL after each liquid bowel movement • Clonidine: a2-Adrenergic agonists inhibit intestinal electrolyte secretion. A clonidine patch that delivers 0.1–0.2 mg/d for 7 days may be useful in some patients with secretory diarrheas, cryptosporidiosis, and diabetes. . Octreotide: This somatostatin analog stimulates intestinal fluid and electrolyte absorption and inhibits secretion. Furthermore, it inhibits the release of gastrointestinal peptides. It is very useful in treating secretory diarrheas due to VIPomas and carcinoid tumors and in some cases of diarrhea associated with AIDS. Effective doses range from 50 mg to 250 mg subcutaneously three times daily. A dosage of 4 g one to three times daily is recommended • Cholestyramine: This bile salt binding resin may be useful in patients with bile saltinduced diarrhea secondary to intestinal resection or ileal disease