Document

advertisement

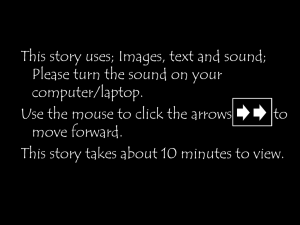

White Russians/Page 1 of 6 WHITE RUSSIANS ~ by Tony Beck CHAPTER ONE: OXFORD STREET SANTAS As 1960 and the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower drew near their ends, 1961 and John F. Kennedy waited in the wings. The cold war stood at an elevated level, due to the so-called U2 Spy Plane Incident, and people were privately building bomb/fallout shelters. However, none of that concerned twenty-one-year-old Sophia Stravnova, sitting in her seat on an English chartered bus. Her thoughts actually were of the Soviet Union, but about how returning to it seemed a death sentence. On a sketchpad, she absentmindedly wrote 1961. After looking at it for a minute, she showed Milla, seated next to her, that the number, when turned upside-down, still read 1961. As the ballet company’s hired bus turned into London’s busy Oxford Street, it met with a solid traffic jam. On the sidewalk up ahead, a rain-washed assembly of war veterans dressed in Santa Claus costumes slowly grew in number as the rest of the forty-four Santas filed across the intersection. The company’s director and the English driver stepped off the bus to speak with traffic police, and Misha, the odious security man/Communist Party watchdog, stood at the open door keeping his beady eyes on the troupe. When the director returned, he announced in Russian, “There will be a short delay while the rest of these undisciplined buffoons come across the road. They will be marching past us along the sidewalk, and you will all get a good look at these ridiculous hooligans. Don’t worry; we will be at the airport on time, and soon we will be home.” Sophia gazed along the sidewalk and began sketching the red-hooded men in their traditional Father Christmas cloaks. The robes brought to mind some red velvet material in one of her wardrobe trunks, carried in the hired lorry that followed directly behind the bus. Directly behind the lorry, she knew, would follow a car from their embassy occupied by two KGB men. The Santas’ beards looked to be made of makeup artist Milla’s cotton batting. Sophia’s thoughts strayed to a trapdoor in the lorry’s wooden floor, which she and Milla had discovered while preparing to load the wardrobe. A quick inspection of this emergency escape door had shown its latch and hinges were freshly oiled and it opened without effort or noise. They had held it open just long enough to see a clear path to the road below and to check for electronic surveillance White Russians/Page 2 of 6 devicesa skill possessed by most young, city-dwelling Soviet citizens. The first costume basket to come aboard had served to conceal the trapdoor’s existence. Nebulous thoughts that had haunted Sophia since before the flight from Moscow were now congealing. Ten days earlier, she had pondered both her past and future while at a well-attended state funeral held for her last living relativeher grandmother, Katarina Stravnova, a celebrated ballerina. The family had been eight strong at Sophia’s birth, but by 1946, conquest, war, famine, and death had spared only the youngest member, Sophia, and the oldest, Katarina. Sophia knew she would have to forsake her romantic desires by marrying a man before some bureaucrat discovered she had no family within the Soviet Union, and her official file would be stamped international travel disallowed. Petty bureaucrats liked nothing more than stripping away privileges from members of the elite professional artist class. With her influential grandmother gone, Sophia’s position as assistant wardrobe mistress of the Bolshoi Theatre Ballet would soon be gone, as well. She envisioned her name on a KGB to-be-watched list. With her socio-political status so diminished, she would be lucky to find work in the garment factories of Minsk. And so it came as no surprise when the director summoned her to his office just one day before the company’s departure to England. However, instead of the imagined dismissal, she received a promotion. The director informed her that Comrade Kropotkin, the wardrobe mistress, had taken ill and could not travel. Expressing his complete confidence that Sophia could adequately fill the position, he congratulated her, adding that he had insufficient time to acquire a proper assistant, one cleared for international travel, so members of the chorus would have to assist her. She would be solely in charge of wardrobe for the London engagement. While sketching Santas from the bus, an overwhelming sense of resolution gripped Sophia. She found herself amazed at how crystal-clear the future appeared: one possible future. With pulse racing, she stood and approached the director. Feigning a worried look, she told him that they must check the wardrobe, as some valuable costume jewelry may have been left behind. The director gave his consent, and Sophia briefly returned to her seat row, placing the sketchpad on her seat while stealthily kissing Milla on her forehead. She then set off for the wardrobe lorry andwin or losea new year turned upside-down. White Russians/Page 3 of 6 As she had expected, the repugnant Misha walked with her along the sidewalk, persistently making his tiresome innuendoes regarding her love life – or absence of suchpausing only when they stopped to speak with the lorry driver. Sophia wished she had Misha’s knowledge of English, notwithstanding all the vulgarisms he would have memorized. As they continued alongside the lorry, she deliberately dropped a glove into the gutter, where a stream of rainwater flowed over it. Crouching down to retrieve her glove, she quickly scanned the lorry’s underside. While rising, she observed the side-view mirror. Her plan would work, provided that Misha stayed true to form and did not miss the opportunity to butter up the KGB escortthus leaving her alone with the wardrobe. At the lorry’s rear door, the driver helped her up and handed her a torch. Misha, as counted on, waited with the KGB men. Sophia wondered if they would be less chummy by day’s end, or more so, having foiled her plot. The plan could still be aborted, and her inner voice of reason begged her to do so. She recalled how each of the troupe members had sworn an oath not to attempt defection to the West . . . how the party officials had made it clear that anyone breaking this oath would live out his or her short life in the misery of a Siberian gulag. Yet, Sophia pressed on, channeling her fear into action. Despite the faulty torch flickering on and off and drops of sweat stinging her eyes, she found what she needed. From a utility trunk she took a large pair of scissors and a handful of safety pins. From another trunk came a roll of red velvet, and she cut off five meters. All proceeded according to plan, but as she opened one of Milla’s two makeup trunks, a smaller case fell noisily to the floorprompting the driver to climb up. He asked with a Cockney accent, “Everything alright, Miss?” “Five minutes,” she replied in her best English. When the driver had climbed back down, Sophia quickly found a large swath of cotton batting, cutting off a piece sufficient for her needs, and after a few minutes of extremely skillful impromptu costuming, she stood ready before the trapdoor. White Russians/Page 4 of 6 Time now seemed suspended, for she had reached the point of no return. Up to this moment, she could have claimed her masquerade to be a great joke for the troupe, but once through the trapdoor, she would be “Alisa Down the Rabbit Hole”and her life would change forever. With a pounding heart, she switched off the torch and slowly opened the trapdoor, admitting into the silent, black interior the busy street sounds and a glowing orb of daylight, in which she stood like a fairytale wizard. On the bus, Milla admired the recent drawings in Sophia’s sketchbook. Suddenly, she gasped and looked toward the Santas, who were now coming down the sidewalk. She squeezed in with the others who were joyfully swarming the windowsand as the Santas marched past, only she noticed the red-hooded figure scuttling from beneath the lorry to become the forty-fifth Santa. Tears streamed down Milla’s cheeks to meet with a broad smile. When they were well beyond the KGB car, Sophia shouted, “Political asylum!” to the others who, she now realised, were mostly three sheets to the wind. Several minutes after the Santas had passed, questions as to Sophia’s whereabouts were answered. The director, Misha, and the KGB men stood in the back of the lorry looking down at the open trapdoor, remnants of red velvet, scraps of cotton batting, and Sophia’s soaked glove, the fingers of which she had arranged to form an unladylike gesture aimed at Misha. When the penny dropped, the KGB men chased after the marchers, running along the sidewalk and pushing past umbrella-wielding Oxford Streeters amidst protests of “I say!” and “Steady on!” But they were too late. Sophia sat in a taxicab between her two savior Santas, a former army captain and his sergeant-major, who were escorting her to the sanctuary of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Six years later, British citizen Sophia Star (formerly Sophia Stravnova) opened Sophie’s, which became one of the most successful fashion boutiques of London’s famous Carnaby Street. Two years after that, still unmarried, she gave birth to a baby girl, Katarina. White Russians/Page 5 of 6 Each December, Sophie would make ready the Santas’ costumes, and she did so until the final parade in 1968, as the tradition gave way to more serious and sober street marches. Sophie’s exists to this dayalthough bought out by corporate interestsand upon the wall, as it always has done, hangs a mounted enlargement of the 1960 London Star news photo of the marching men, entitled, “Oxford Street Santas.” That is how my grandfather, the army captain savior Santa, recounted the story. I call him my grandfather, but, more accurately, he was simply the biological father of my mother, Katarina Star. Grandma Sophie had wished to remain unwed. Mom grew up in Chelsea through the psychedelic 60s and 70s, through the Disco Days and into the glitzy, glam-rock 80s, where she came into her own as a free-spirited, très chic party girl. My birth slowed her down somewhat, though, and being single, she began nesting with various artists, actors, and musicians, all of whom I would call uncleor aunt. That environment was not what social workers of the day would call wholesome, or even normal, but it brimmed over with fascinating people, loads of laughter, and kind-heartedness. Eventually, Mom hooked up with Axel, a Russian-Canadian artist who legally went by that single name. We moved to his beautiful home in Vancouver, and there, Mom and he were married. She and I became Canadians, but kept “Star” as our surnameand we three were the happiest Canuckleberries ever to be. Not until I’d graduated university, did I realize we were in trouble. I’d known Axel had been drinking more than his usual copious quantities of vodka, but I’d been unaware that it had become a serious problem. To make matters worse, he hadn’t produced any good work in over three years; he was going broke; and he’d taken up with one of his former models. Mom and Axel divorced the following year. Our home had to be sold to settle multiple mortgages, and mom went back to London. She wanted me to come with her, but I stayed on in Vancouver, as I then considered myself an actor and wanted to make a name in Canadian theatre before giving London a shot. Besides, my Anna was still at school. This brings me to my sad and sordid tale. White Russians/Page 6 of 6 END OF SAMPLE Copyright notice: All information contained in this document is copyrighted. No part of this document or any of its contents may be reproduced, copied, modified or adapted, without the prior written consent of the author.

![Procopios: on the Great Church, [Hagia Sophia]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007652379_2-ff334a974e7276b16ede35ddfd8a680d-300x300.png)