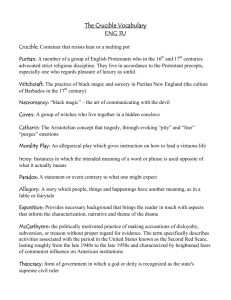

What should you have done with it?

advertisement