Langston Hughes biography

advertisement

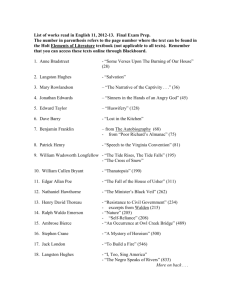

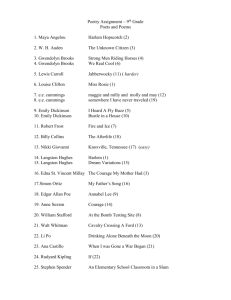

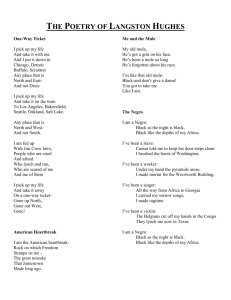

Hughes, Langston Sex: Male Born: Joplin, Missouri, United States 01 February 1902 Died: New York, New York, United States 22 May 1967 Activity/Profession: Poet (b. 1 February 1902; d. 22 May 1967), poet, novelist, short-story writer, essayist, playwright, journalist, columnist, and cultural leader. James Mercer Langston Hughes was the preeminent African American poet of the twentieth century, but he wrote in almost every literary genre during his five-decade career. He was born in Joplin, Missouri, but spent his childhood years in Lawrence, Kansas, with his maternal grandmother, Mary Langston, while his mother, Carrie Langston Hughes, a teacher, looked for employment and marital stability elsewhere. Soon after Langston's birth in 1902, his parents separated. His father, James Hughes, embittered by racist experiences in the United States, left for Mexico, where he owned a ranch, practiced law, and collected rent from tenement houses he owned. After his grandmother died, Langston lived for two years with family friends, James and Mary Reed. As an artist Hughes saw life and art as closely intertwined, and there appears to be an intimate, if sometimes inverse, relationship between Hughes's own family history and his commitments as an artist and opinion maker. Having grown up as a lonely child with frequently changing circumstances, attending adults, and locations (including Illinois and Ohio with his mother and stepfather), Hughes developed a strong link to African Americans as a whole and to their historical experience. In many of his poems, including his first published poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1921), he spoke in the collective voice of all African Americans in powerful ways rarely matched in literature. But certainly there was much in his distinguished family history to inspire him, too. Mary Langston (b. 1836) especially instilled in her young and curious grandson the kind of racial pride and courage that her two husbands—Lewis Sheridan Leary and Charles Langston—had displayed in their lives. Hughes rejected his own father's bitterness to form a strong commitment to working for the many causes that touched black American lives. Langston Hughes. In Paris, France, 1938. New York World–Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress view larger image Hughes attended schools in Kansas and Illinois and graduated from high school in 1919 in Cleveland, Ohio. His mother often fought successfully to get him into decent schools in white neighborhoods, and he was generally liked and respected by his classmates. He began writing poetry as a high school student, inspired by the writings of Carl Sandburg and Paul Laurence Dunbar. After high school he spent a year in Mexico with his father and then enrolled at Columbia University as an engineering student. Hughes spent only one year at Columbia. By then he knew that he wanted to be a writer and had already published a few poems in The Crisis and in The Brownies’ Book, both edited by W. E. B. Du Bois. Leaving New York in 1923, Hughes signed up as a crewman on a freighter, SS Malone, making it possible for him to live for six months in West Africa and Europe. In 1924 he lived in Paris and worked as kitchen help in a restaurant for a few months. Later that year he lived with his mother in Washington, D.C., working for some time as a personal assistant to Carter G. Woodson at the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. While working as a busboy at the Wardman Park Hotel in the District of Columbia, he had an opportunity to show a few of his poems to the poet Vachel Lindsay, who was quite impressed and brought Hughes some welcome publicity. By early 1926 Hughes was dividing his time between Harlem and Lincoln University, a historically black college in Chester County, Pennsylvania, where he was enrolled as an undergraduate. His classmates at Lincoln included the future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, the future president of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah, and the musician Cab Calloway. For most of his life Hughes made his home in Harlem, where he died of complications arising from abdominal surgery to deal with prostate cancer. By the time he died, he had authored or edited forty-seven books. He was the first African American writer to support himself successfully from his income as a writer. He was also the first American poet to embrace jazz and blues in his writing. He received numerous honors and awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1935 and the NAACP's Spingarn Medal in 1960, as well as honorary degrees from Lincoln and Howard universities. He was also elected a fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Throughout his life Hughes helped and inspired fellow artists around the globe, and his own work was translated into many languages. Fluent in Spanish, he formed a close bond with many Spanish-language poets, translating the poetry of writers such as Nicolás Guillén, Frederico García Lorca, and Gabriela Mistral. Writers who acknowledged his influence on their writing and style include Guillén, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire, and Jacques Roumain. In 1981 Hughes's home in Harlem, 20 East 127th Street, was given landmark status, and the block was renamed “Langston Hughes Place.” In 1973 the City College of the City University of New York started awarding an annual Langston Hughes Medal. In the early 1940s Hughes began gifting his papers to the James Weldon Johnson Collection at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Some of his papers are also on deposit at the Langston Hughes Memorial Library at his alma mater, Lincoln University. The Harlem Renaissance and the Fire!! Rebels. In the mid-1920s Hughes kept company with other young writers and artists, and they met frequently at the Harlem quarters of Wallace Thurman, who had arrived in Harlem from Salt Lake City and Los Angeles on Labor Day 1925. Hughes admired Thurman's critical acumen and turned to him often for feedback on his writing. Along with Zora Neale Hurston, John P. Davis, Bruce Nugent, Aaron Douglas, Eric Walrond, Helene Johnson, Dorothy West, and others, Hughes and Thurman formed a literary group centered on the short-lived literary magazine Fire!! Together and individually they challenged the didacticism of public figures such as Du Bois, even as they maintained significant critical distance from the mentoring and promotional ways of cultural pluralists such as Alain Locke and Charles S. Johnson. Although in essays and reviews such as “Nephews of Uncle Remus” and “High, Low, Past, and Present” Thurman claimed a distinctive voice as an early theorist and public intellectual that goes well beyond the ideas articulated in Hughes's famous essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” (1925), Hughes spoke most resonantly and memorably for his Harlem Renaissance peers when he stated in that essay: "We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves." Hughes and his colleagues recognized that “the Negro artist works against an undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding from his own group and unintentional bribes from the whites.” So they felt compelled to engage both the black bourgeoisie and the white critics in debates regarding issues of aesthetics and representation. They recognized that their need to reject pressures from both these groups impinged in one way or another upon their individuality as well as their freedom as artists. All of the younger artists associated with Fire!!, as well as a few others, opposed the programmatic and promotional ideologies of the older generation of black writers, leaders, and intellectuals such as Du Bois, Allison Davis, Aubrey Bowser, and Benjamin Brawley. But because—like Ralph Waldo Emerson during the American renaissance—Du Bois was a towering presence during the peak years of the Harlem Renaissance, he was often their favorite target. By wrestling courageously in the 1920s and 1930s with the intricacies of racial constructions in the United States, Hughes and others surely facilitated the process by which future generations of African American writers developed a much more complicated understanding of issues surrounding art, representation, and group identity. Although Hughes shared the Fire!! group's desire for assertive independence, he was more invested as an artist than, say, Thurman or Hurston in exploring themes of racial pride and racial exclusion in the rhythms of common black speech, using a folksy style that combined humor, wit, and irony. He was also arguably the most skillful among the younger Harlem Renaissance artists in navigating the troubled waters of racial and representational politics during these years. Never losing sight of his own goals as a budding writer, he was careful to develop literary connections and friendships that helped his career. In 1925 he won a literary competition sponsored by Opportunity magazine, edited by the sociologist Charles S. Johnson for the National Urban League. Around this time Hughes also met Carl Van Vechten, a white jazz critic and writer who had a penchant for interracial cultural interaction. Van Vechten arranged the publication of Hughes's book of poems The Weary Blues (1926), which has all of Hughes's signature themes as a “social poet” (Hughes's own term). In 1927, through Locke, Hughes met Charlotte Quick Osgood Mason, a rich white woman who had developed an interest in African art, which she believed could help American blacks regain their lost self-respect. For two years, from 1928 to 1930, Mason supported Hughes most generously, and he completed his only novel, Not without Laughter (1930), a bildungsroman that captures the diverse details of African American life and culture surrounding the young hero Sandy's conflicts centered in class and lifestyle. The breakup with Mason was quite traumatic for Hughes and propelled him toward a mistrust of capitalism that was certainly in the air in the wake of the Wall Street crash in 1929. From Revolution to McCarthyism. The modest commercial success of Not without Laughter opened up some new opportunities for Hughes. In 1931, following Mary McLeod Bethune's advice, he began a poetry reading and lecture tour in the South, and in 1932 he made a trip to the Soviet Union along with Louise Thompson and others with the goal of making a film there that would portray the living conditions of black Americans at that time. The film never materialized, but Hughes traveled extensively in the Soviet Union and also visited China and Japan on his trip home. During the 1930s he wrote many revolutionary poems that were published in the newspaper of the Communist Party USA. He also supported the party's campaign to free the Scottsboro Boys and traveled in 1937 to Spain to report on the Spanish civil war for the Baltimore Afro-American. He was involved for a while in the John Reed Club and other leftist activities. In 1934 Hughes published Ways of White Folks, his first collection of short stories, which included “The Blues I'm Playing,” an intricate fictional treatment of his relationship with Mason. As part of his activism he focused on the theater in the late 1930s, establishing the Harlem Suitcase Theater (1938), the New Negro Theater in Los Angeles (1939), and the Skyloft Theater in Chicago (1941). In 1941 he also cowrote the screenplay for Way down South, but he was unsuccessful in getting more work in Hollywood because of rampant racism in the industry. However, his success as a playwright gave him a measure of financial stability that allowed him to buy his Harlem home. In 1943 Hughes started writing a regular column for the Chicago Defender regarding a folksy character in Harlem named Jess B. Semple (Just Be Simple), who offered his witty opinions on black life and culture for well over two decades. Hughes's newspaper columns continued until 1965 when the last of the five books of Simple tales appeared. In 1940 he published The Big Sea, the first of two autobiographies, which includes his charming and influential narrative of the Harlem Renaissance years. Its commercial possibilities were overwhelmed by the appearance of Richard Wright's Native Son in the same year. Hughes's second autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander, wherein he wrote freely about his year in the Soviet Union, appeared in 1956. During World War II, Hughes wrote jingles and newspaper columns to encourage the sale of war bonds and participated actively in the Double V campaign of the black press. Some of Hughes's leftist associations and writings during the 1930s came to haunt him in the 1950s. He was accused of being a Communist, but he always denied it. In 1953 he was called before Joseph McCarthy's Senate committee, where he chose not to testify against friends but answered questions regarding his own activities and works. Shaken by the experience and afraid to lose face and livelihood as a writer, he distanced himself from Communism, and his Selected Poems (1959) left out most of his radical poems. In the 1960s some younger black writers found him lacking in “militancy” on black causes. Though his posthumously published Panther and the Lash (1967) was aimed at establishing solidarity with these writers, Hughes preferred to do so without raw anger and what he considered hateful racial chauvinism. The Social Poet. Although Hughes wrote in many voices throughout his checkered career, he was always the quintessentially “social poet,” whose folksy and deceptively simple expression sometimes concealed his subtlety and complexity as a writer and thinker. For Hughes, being a social poet meant writing not just about “roses and moonlight” but also about “poverty, trade unions, color lines and colonies” (“My Adventures as a Social Poet”). As a writer and public figure Hughes remained committed to challenging and subverting the many negative stereotypes that affected the life chances of most African Americans. In his writings he explored the richness and diversity of the African American experience, which he saw as closely connected to all of human history and not as something apart. As he noted, “My seeking has been to explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America and obliquely that of all human kind” (quoted in Rampersad, vol. 2, p. 418). As his biographer Arnold Rampersad and others have noted, Hughes was both a particularist and a cosmopolitan, and he did everything in his long literary career to make poetry and art accessible to as many people as possible. Bibliography Berry, Faith. Langston Hughes: Before and beyond Harlem. Westport, Conn.: Lawrence Hill, 1983. Hughes, Langston. The Collected Works of Langston Hughes. 16 vols. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001–2004. Hughes, Langston. “My Adventures as a Social Poet.” Phylon 8, no. 3 (1947): 205–212. Reprinted in Langston Hughes, Good Morning, Revolution: Uncollected Social Protest Writings, edited by Faith Berry, pp. 135–142. New York: Lawrence Hill, 1973. Hughes, Langston. “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Nation, 23 June 1926, pp. 692–694. Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes. 2 vols. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986–1988. Singh, Amritjit. “Beyond the Mountain: Langston Hughes on Race/Class and Art.” Langston Hughes Review 6, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 37–43. Thurman, Wallace. Collected Writings of Wallace Thurman. Edited by Amritjit Singh and Daniel M. Scott III. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2003. CITATION FOR THIS SOURCE: Singh, Amritjit. "Hughes, Langston." Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Ed. Paul FinkelmanNew York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. Mon Dec 17 22:22:07 EST 2012. <http://www.oxfordaasc.com/article/opr/t0005/e0587>.