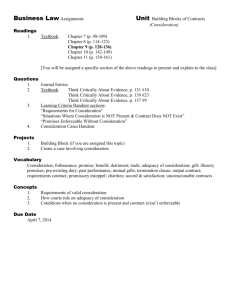

Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions

advertisement

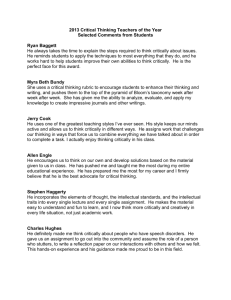

CRITICAL THINKING Understanding The Principles And Processes Of Thinking Well Chapter 6 Thinking Critically About Research By Glenn Rogers, Ph.D. Copyright © 2013 Glenn Rogers Thinking Critically About Research What has critical thinking got to do with research? Research is what generates the data to be analyzed in the critical thinking process. Without data to analyze, what are we going to think critically about? The link between doing research and thinking critically is a vital one. The Need for Research If someone claimed that most people in America believe that capital punishment is a deterrent to capital crime, how would you know whether or not that is the case? If someone argued that capital punishment is, in fact, a deterrent to capital crime, how would you know whether or not that was the case? The only way you can know whether or not either of those claims is true, is to do research and see if the data supports the claim being made. Thinking Critically About Research The Need for Research What if you believe that the shift in higher education to a customer service orientation, with the students being customers who must be served and given what they want, has led to the devaluing, the dumbing down, of American higher education? You suspect that this is true, but you cannot make a case for it without facts. How do you get the facts you need to make your case? You do research. Research is a necessary part of the critical thinking process because you can’t do critical analysis if you have nothing to analyze. Anyone can make any kind of a claim. But you cannot know whether or not the claim is true unless you research it. Truth doesn’t just fall out of the sky into your lap. You have to go find it. Good critical thinkers will learn how to do thorough research. Thinking Critically About Research Facts vs. Fantasy Popular culture is full of myths, legends, and fantasy, that people accept as true, often referring to what “they say” (whoever they are) as if it was fact. One is that Mr. Rogers was a Navy Seal. Another is that there are giant alligators in the sewers under New York City. Yet another is that if you leave a tooth overnight in a glass of Coke a Cola, by morning it will have been dissolved. None of these myths is true. Yet they are often repeated as if they were facts. Thinking Critically About Research Facts vs. Fantasy What is a fact? A fact is something that is actually the case. That there is an apple on my desk is a fact because it is actually the case that, at this moment, as I write this sentence, there is an apple on my desk. There is also a stack of books and a computer, and a cup of tea on my desk. These things are facts. They are the case. In his book, Metaphysics, Aristotle observed, “To say that what is, is not, or to say that what is not, is, is false and to say that is, is, or that what is not, is not, is true.” This was Aristotle’s way of saying that if you say something is a fact when it isn’t, you are wrong. If you say something is not a fact when it is, you are also wrong. A fact is a fact. What the critical thinker must do is research in order to discover what is, in fact, the case. Aristotle, Metaphysics, 4.7. Thinking Critically About Research Objective vs. Subjective The objective vs. subjective nature of reality can be a tricky topic because it works at two levels. At one level we have objective truth. There is an objective reality and objective truth is a part of it. But how do we know objective truth exists? By a combination of two things: reason and experience. For instance, as discussed earlier, I know I exist. I am sitting at my computer thinking about myself thinking. I can’t be thinking without the ability to think. And if I have the ability to think, then whatever else I might be (or might not be) I am at least a thinking being—which means I exist. I cannot simply be a character in some other being’s imagined reality. The only being who could pull off something of that magnitude (creating an imaginary reality where I thought I existed but did not) would be God. And God, given what is required for God to be God, that he must be good and kind and benevolent, would not (nor have reason to) perpetrate such a ruse. Thinking Critically About Research Objective vs. Subjective I am not an imaginary character in a nonexistent reality. I am thinking about myself thinking because I am a thinking being. Therefore, I exist. I am an objective reality. And as such I can think about other objective realities, such as mathematical realities. 2+2=4 is an objective reality. 2+2 is not 4 if I want it to be or think it is, or if you want it to be or think it is. 2+2 is 4 because it is 4. It is an objective reality, an objective truth. And it is an objective truth that can be comprehended (known) by the human mind. We can experience other sorts of objective truth—the physical laws of the cosmos, for instance, that function with absolute regularity. For example, if you add vinegar to baking soda you get the same result every time. Not some of the time, not most of the time. Every time. Why? Because objective reality exists. Thinking Critically About Research Objective vs. Subjective An objective reality exists; an objective truth exists. There are real things and real facts about those things. The critical thinker understands that this is the case. But subjective opinion also exists. During the 2013 spring break I led a group of students on a tour of several major European cities. Paris was one of them. While in Paris, we visited the Louver Museum. One of the paintings we saw was the Mona Lisa, perhaps the most famous painting in the world. Seeing it was interesting. Personally, however, I did not think it was a beautiful painting. The color scheme is rather bland and the woman in the painting (is her name Lisa or Mona?) is rather ordinary looking. I don’t think the Mona Lisa is a beautiful painting. That, however, is my subjective opinion. I think Scarlett Johansson is a beautiful woman. That, too, is my subjective opinion. There are facts and then there are opinions. The good critical thinker will know the difference between the two. Thinking Critically About Research Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions Once we enter the realm of opinions we must differentiate between informed and uninformed opinions. Informed opinions are worth considering; uninformed opinions are not worth the breath it takes to articulate them. An opinion is a judgment one forms about a matter that is not factual in nature. An opinion is linked to that which is subjective in nature because it is not factual. For instance, what is beautiful? I can have an opinion about what I think is beautiful, but what is beautiful or not beautiful is not a factual kind of a thing. I cannot say that it is a fact that Scarlett Johansson is beautiful because, as the saying goes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The nature of beauty is that it involves a subjective judgment. Thinking Critically About Research Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions There are some subjective judgments that are based simply on personal preference. I, for instance, think pepperoni pizza is the best pizza. My wife, however, believes that mushroom pizza is the best. These are completely subjective judgments, preferences, if you prefer. However, there are some subjective judgments that must be based on the thoughtful analysis of the available information. An opinion based on the thoughtful analysis of the available information is an informed opinion. An opinion that one has formed without thoughtful analysis of the available information is an uninformed opinion. Thinking Critically About Research Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions For example, a few semesters ago, I had a gentleman in my Ethics class who had an opinion on whether or not a developing fetus is a person. We had discussed the arguments for and against the personhood of the developing human fetus. This gentleman stated emphatically that the fetus was not a person, and therefore had no rights. I acknowledged his opinion and then asked for his reasons for holding that opinion. “Why,” I asked, “do you think that the developing fetus is not a person?” He replied, “Because it isn’t.” Thinking Critically About Research Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions “Yes,” I said, “I understand that it is your opinion that the developing fetus is not a person. I get that. But I would like to know why you think that? Why isn’t the fetus a person?” “Because it isn’t,” he replied. “Yeah, but why isn’t it?” I asked. “Because it isn’t.” “But why isn’t it?” “Because it isn’t.” “Okay,” I said, “so it appears that you have an opinion, but apparently you have no reasons for holding that opinion. You don’t seem to have any reasons for why you believe what you believe. Is that the case?” He would not respond. Thinking Critically About Research Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions This is an example of an uninformed opinion. He had an opinion and felt very strongly about it. But he had no reasons (at least none that he could articulate) for why he held that opinion. It was simply an opinion, which made it an uninformed opinion, because concerning the status of fetuses, there are a great many factors to be considered. It did not appear, however, that he had considered any of them. Thus, his opinion was uninformed. Thus, his opinion was worthless. And that is the point: from a critical thinking perspective, an uninformed opinion is a worthless opinion. If there is information to be analyzed and considered, and it is not analyzed and considered, no critical thinking has occurred. And if no critical thinking has occurred, whatever minimal kind of thinking has occurred is not worth much. Thinking Critically About Research Informed vs. Uninformed Opinions Even in matters of opinion, critical thinking is crucial. Good critical thinkers will look for whatever information there is about whatever subject is being considered and factor that information into their opinion about that subject. When that occurs you have an informed opinion. Evaluating Sources How reliable is the data you’ve gathered? The answer to that question has a lot to do with where you got the data. Some sources are reliable; some are not. Thinking Critically About Research Evaluating Sources A lot of research is done on the internet. There is nothing wrong with that per se. But the internet is a big place. It is unregulated and people can post, pretty much, whatever they want on their website. That means that when you go online to do research, you need to do some research on the reliability of the sites you visit. How reliable is the information they give you? Websites that end in .gov, .edu, and some that end in .org, are more likely to provide reliable data. Though some organization websits, those that end in .org publish material that is extremely biased. Thinking Critically About Research Evaluating Sources Another concern you should pay attention to, is the credentials of the person providing the data. Who is this person? What is her education? With whom is she affiliated? Where did she get the information that is being passed on to you? Does she have a vested interest in the issue under consideration? Is this person a professor? A journalist? Is she affiliated with a legitimate organization? Does she work for the government? If she does work for the government, in what capacity? Is she representing a candidate’s platform? If so, her legitimacy is less certain than if she works in a sector of the government concerned in an impartial manner with the data she is presenting. Thinking Critically About Research Evaluating Sources Some information you may need may not be available online. You may occasional have to go to a library and look something up in a book. The questions you must ask for print media are the same basic questions you must ask regarding electronic media. Who wrote this book? Who published it? Does the person who wrote it have a vested interest in how this information is used? What is the author’s education? These kinds of questions are essential. Wikipedia Good critical thinkers pay attention to the reliability of the data they gather, going to sources that are more rather than less reliable. Thinking Critically About Research Academic vs. Popular Sources One of the most basic concerns regarding reliability is whether or not the source of the information is popular or academic. An academic source has some association with higher education. It may be a book written by a professor, a journal article written by an academic, a report produced by a committee associated a college or university, an administrator of a college or university, and so forth. Academic sources can also be material posted by professors online: course syllabi, power point presentations, papers, or You Tube videos recorded for viewers. If the person is an academic, which means having an M.A. or a Ph.D., the information they provide may usually be considered reliable. Thinking Critically About Research Academic vs. Popular Sources However, this is not always the case. Sometimes even academics make crucial mistakes. Take, for example, the idea that many physicists are discussing that something can, in fact, come from nothing. This is simply not the case. Either, they are being intentionally dishonest, or they completely misunderstand the idea of nothing as philosophers use the term. Or consider another idea often advocated by physicists: the theory of multiverses is actually based on some kind of evidence. Just because a theory has an internal mathematical consistency does is not evidence that that which is postulated in the theory exists. The multiverse theory is a theory. Is there any evidence that it is true? No. None whatsoever. There is only a theory. Thinking Critically About Research Academic vs. Popular Sources So even when a source is an academic source, the information is not automatically reliable. A physicist saying he can make a coherent argument is favor of the multiverse argument, is not that same as saying I have evidence that the theory is true. Sometimes people espouse positions they desperately need to believe. Sometimes they claim they have support for their position when they do not. Good critical thinkers will critique the reliability of the evidence with which they are presented to see if, in fact, it is reliable. Thinking Critically About Research Depth and Breadth in Research One of the biggest problems undergraduates have when doing research is not digging deep enough. They assume that upon reading one or two articles they have the data they need. Reading one article on a topic is not doing research. Reading two or three articles is not doing adequate research. The general rule for research is, when you think you understand the issue and know the basic data, you’ve done the introductory work. You know the basics. Now you need to understand the challenges, the problems, the caveats, the exceptions, the different perspectives or positions held on the subject by those who are specialists in field. So basically, when you first think you are done researching, you are not done. You have to keep digging. Thinking Critically About Research Depth—How Deep Does this Go How deep should you dig? As long as you continue to find new ideas, new insights, new problems, new challenges, and new perspectives you need to keep digging. As long as there is stuff down there to find, you are not done. Keep digging. One thing students have difficulty with is in knowing where to go next. They found a couple of articles on the subject they are researching, but they don’t know where else to go. Assuming that you are utilizing academic resources (and that is what you should be using), you should always check the works cited section at the end of the article. What sources did the person who wrote the article use in doing her research? Thinking Critically About Research Breadth—What Other Issues or Concerns are Related to This Once you understand how deep a subject is, you need to figure out how wide it is. That is to say, you need to discover how many issues and concerns are associated with this particular topic. For instance, suppose you somewhere encounter the idea of social justice that includes the idea that wealth has been distributed in an unfair (unequal) manner and needs to be redistributed. Suppose these ideas intrigue you because you have never understood wealth as having been distributed by someone, that is, distributed by some agency or entity. Suppose also that you decide to research the subject. Let’s say that you go to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and do a search for social justice. You discover an article on Western Theories of Justice, by Pomerleau. Thinking Critically About Research Breadth—What Other Issues or Concerns are Related to This The article will refer to fifteen philosophers, from ancient times to modern, who have had something to say about social justice. You will also notice that the references section, between the primary and secondary resources, includes seventy-six references. As you read the article and think about the subject, you will discover that one cannot discuss social justice in any thorough manner without also discussing: 1) economic systems (specifically the differences between capitalism and socialism), 2) assumptions regarding the right to private property, 3) the meaning or meanings of equality, 4) the meaning of liberty, 5) the limits of social responsibility, 6) the differences between a distributive system and an acquisition system, 7) whether or not, in the United States (or other capitalistic economies) there exists an agency or entity that distributes wealth, and 8) the morality of forcing people to give up their legally acquired and therefore rightfully owned property in order to “redistribute” it to people who did not earn it. Thinking Critically About Research Breadth—What Other Issues or Concerns are Related to This Obviously, the topic of social justice is a broad subject, touching on many other issues and concerns. Even if you dig deep into one of the eight concerns noted above, you will not be finished with your inquiry until you have researched all eight of the related issues. Good critical thinkers will understand that concerns about breadth go handin-hand with concerns about depth. The critical thinker will research not only deeply, but broadly as well. Thinking Critically About Research Do You Know What There is to Know About This Subject How do you know when you’ve done enough research? You’ve done enough research when you know what there is to know about the topic under consideration. When you get to the point that you can anticipate what an author is going to say about the subject, you are getting close to the end of your research project. When you read an article and you know enough about the subject to know what the author left out or got wrong, you have probably done sufficient research into the subject. Thinking Critically About Research Do You Know What There is to Know About This Subject Perhaps your assignment is to write a ten-page research paper, on a topic you were assigned or on one of your own choosing. Suppose it is a broad topic like social justice. How much research is required for you to write a tenpage paper? That will depend on the exact wording of your research question. Basically, when you have a thorough grasp of the subject under consideration and when you can answer your research question, you are ready to write your paper. But at that point you will also realize that there is much more to the subject than what you have thus far examined. You will realize that you have only begun the process and have only skimmed the surface. Thinking Critically About Research Citing Sources A survey of over 63,700 US undergraduate and 9,250 graduate students over the course of three years (2002-2005)--conducted by Donald McCabe, Rutgers University--revealed the following: 36% of undergraduates admit to “paraphrasing/copying few sentences from Internet source without footnoting it.” 24% of graduate students self report doing the same 38% admit to “paraphrasing/copying few sentences from written source without footnoting it.” 25% of graduate students self report doing the same 14% of students admit to “fabricating/falsifying a bibliography” 7% of graduate students self report doing the same doing so Thinking Critically About Research Citing Sources 7% self report copying materials “almost word for word from a written source without citation.” 4% of graduate students self report doing the same 7% self report “turning in work done by another.” 3% of graduate students self report doing the same 3% report “obtaining paper from term paper mill.” 2% of graduate students report Plagiarism refers to taking someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as one’s own. When you get an idea from anywhere other than your own mind, it is someone else’s idea. You cannot pass it off as your own. If you do, you are lying and you are committing plagiarism. Thinking Critically About Research Citing Sources Suppose, for instance, that I do a great deal of research into critical thinking and write a book on the subject. The words I use to communicate the ideas I have about the subject are mine. The words I used and the order I used them in are the product of my intellect. They are my intellectual property. Stealing someone’s intellectual property is the same as stealing her car or wallet. Stealing is stealing, regardless of what is being stolen. Many students are under the impression that if something is posted on the internet, it is free for the taking. That is not a valid assumption and it is not true. Material created by another person, regardless of where it is posted or in what format is it made accessible, is still the intellectual property of the person who created it. You cannot take it and pass it off as your own. Thinking Critically About Research Citing Sources I am also the faculty advisor for the Philosophy Club. In our club meetings, we occasionally have students make presentations on different topics of interest. On one such occasion, one student was delivering a presentation on, let’s say, The Theory of Multiverses. He had prepared a handout for everyone. It looked something like this: The Theory of Mulitverses Joe Student The multiverse is a theory in which our universe is not the only one, but states that many universes exist parallel to each other. These distinct universes within the multiverse theory are called parallel universes. A variety of different theories lend themselves to a multiverse viewpoint. Not all physicists really believe that these universes exist. Even fewer believe that it would ever be possible to contact these parallel universes. Thinking Critically About Research Citing Sources The student talked about the subject, presenting a good overview. Everyone was impressed. Then one of the students, impressed with the quality of writing, asked him, “Did you write this Joe?” To which he replied, “Oh, no. I got it off the internet.” Several people reacted, some commenting that he had presented it as if it was his own material. Joe’s reply was, “Yeah, but this is not a for-credit assignment. So it doesn’t matter.” I explained to him that it always matters. What Joe had done, whether he meant to or not, was to present someone else’s words (and ideas) as if they were his own. What he should have done is cited the material as having been written by Andrew Zimmerman Jones and Daniel Robbins in, String Theory For Dummies. Thinking Critically About Research Citing Sources Your college will have specific guidelines for citing references. Whatever the specifics are for your college, learn them and follow them. The only thing you don’t have to cite is your own ideas and your own words. If you use a paragraph or a sentence or even a phrase that someone else wrote, you must give that person credit. What has this got to do with critical thinking? Critical thinkers are intellectually honest. If you are intellectually honest you will not steal the intellectual property of others. If you use it, give them credit for it. Thinking Critically About Research Summary You can’t think critically unless you have something to think critically about. You get data (information) to think about by doing research. Doing research is a crucial part of the critical thinking process. Good critical thinkers understand this. Doing research is about discovering facts. A fact is something that is actually the case. Doing research is an attempt to discover what is actually the case. It is about differentiating between objective reality and subjective opinion. It is also about distinguishing between informed and uninformed opinions. Good research is based on reliable sources, and will, whenever possible, utilize academic sources rather than popular sources. Good research is both deep and broad, and the good critical thinker will always give credit where credit is due, never using someone else’s ideas or words without citing the source.