Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

advertisement

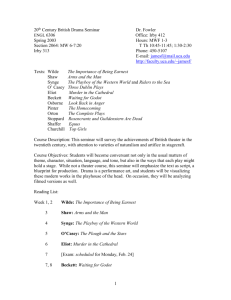

Tom Stoppard I. Introduction to Tom Stoppard Sir Tom Stoppard (born 3 July 1937) is a British screenwriter and playwright. He has written plays such as The Coast of Utopia, Arcadia, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, and Rock 'n' Roll. He co-wrote the screenplays for Brazil and Shakespeare in Love. Tom Stoppard's playwrighting career embodies a fascinating clash of opposites. In an interview, he once said, "I don't write plays for discussion." Yet his writings have been the subject of dozens of academic books and hundreds of critical articles. He has also commented "I've never felt . . . that art is important." Yet many of his characters continually ponder the significance of theater, indeed, the significance all the arts, as part of a perpetual (forever) search for meaning. # He is regarded as the most intellectual dramatist of our time, and his works are permeated (pervade) with cultural allusions and a remarkable depth of scholarship in a dizzying array of fields. Yet his formal education ended after the second year of high school. Finally, despite Stoppard's stature as a "serious" playwright, his writings overflow with fun: parodies, puns, and verbal byplay across multiple languages. # Career By 1960, he had completed his first play A Walk on the Water, which was later re-packaged as 1968's Enter a Free Man. Stoppard noted that the work owed much to Robert Bolt’s and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Within a week after sending A Walk on the Water to an agent, Stoppard received his version of the "Hollywood-style telegrams that change struggling young artists' lives." His first play was optioned, later staged in Hamburg, and then broadcast on British Independent Television in 1963. From September 1962 until April 1963, Stoppard worked in London as a drama critic for Scene magazine, writing reviews and interviews both under his name and the pseudonym William Boot (taken from Evelyn Waugh's Scoop). In 1964, a Ford Foundation grant enabled Stoppard to spend 5 months writing in a Berlin mansion, emerging with a one-act play titled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Meet King Lear, which later evolved into his Tony-winning play Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. In the following years, Stoppard produced several works for radio, television and the theater, including "M" is for Moon Among Other Things (1964), A Separate Peace (1966) and If You're Glad I'll Be Frank (1966). On 11 April 1967 — following acclaim at the 1966 Edinburgh Festival — the opening of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead in a National Theatre production at the Old Vic made Stoppard an overnight success. # Over the next ten years, in addition to writing some of his own works, Stoppard translated various plays into English, including works by Slawomir Mrozek, Johann Nestroy, Arthur Schnitzler, and Vaclav Havel. It was at this time that Stoppard became influenced by the works of Polish and Czech absurdists. He has been co-opted into the Outrapo group, a far-from-serious French movement to improve actors' stage technique through science. "Stoppardian" has become a term used to refer to works in which an author makes use of witty statements to create comedy while addressing philosophical concepts. Stoppard was voted the number 76 on the 2008 Time 100, Time magazine's list of the most influential people in the world. # Personal life Stoppard has been married twice, to Josie Ingle (1965–1972), a nurse, and to Miriam Stoppard (née Stern and subsequently Miriam Moore-Robinson, 1972– 1992), whom he left to begin a relationship with actress Felicity Kendal. He has two sons from each marriage, including the actor Ed Stoppard and Will Stoppard, who is married to violinist Linzi Stoppard. # Theatre: Stoppard‘s plays deal with philosophical issues while presenting verbal wit and visual humour. The linguistic complexity of his works, with their puns, jokes, innuendo(影射、暗讽), and other wordplay, is a chief characteristic of his work. Many also feature multiple timelines. One place to begin with Stoppard, however, is to recognize that after he left school at the age of seventeen, he worked for a few years as a journalist, including several months as a drama critic. This career seems to have inspired in him an almost scientific curiosity about people's behavior, a fascination with how they attempt to maintain personal, emotional, and intellectual balance as they wander through the uncertainties of life. Indeed, the main characters in virtually all his plays conduct a perpetual struggle to affirm their beliefs and values in a bewildering world. # Works Nowhere is this theme more evident than in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1967), Stoppard's first international success. Here he dramatizes the plight of two peripheral characters from Shakespeare's Hamlet, as they meander in and out of the turmoil that ravages the Danish court of Elsinore. The two men are unaware that Prince Hamlet has been ordered by his father's Ghost to revenge the murder of this father, the King, at the hands of Claudius, now ruler of Denmark and husband of Gertrude, Hamlet's mother. Nor have they any sense of the social, political, religious, and sexual implications of this crisis. All they know is that they have been summoned to discover why Hamlet, their old school chum, seems so distressed. Stoppard weaves scenes from Shakespeare with his own sparkling dialogue, creating a memorable portrait of two little men who seek to understand a world hopelessly beyond their ken. # From time to time, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern encounter some Players who entertain at Hamlet's court, and at those moments, the two lost souls tend to regard themselves as actors on the stage of life. This theme is developed further in one of Stoppard's most successful short plays, The Real Inspector Hound (1968), in which two theater critics, casually reviewing a preposterous thriller, are drawn reluctantly into the conflict onstage. On one level, Hound is a delightful spoof of critical jargon and the pomposity that characterizes Stoppard's former profession. Yet more subtly it suggests how any of us, thinking ourselves safe from the hubbub of the world, may nonetheless be whisked unwillingly and even fatally into the chaos. # Stoppard's next major play, Jumpers (1972), accomplishes the seemingly impossible task of bringing the world of contemporary philosophy to the theatre. Throughout the play, the protagonist, who shares the name of twentieth-century British philosopher G. E. Moore, prepares for an academic debate on the nature of moral values. His ruminations are frequently interrupted, however, by the shenanigans of a troupe of renegade gymnast/philosophers who, believe it or not, have seized the British government. Part of the background to these bizarre goings-on is the 1969 landing on the moon, and the way that this event, so Stoppard suggests, altered humanity's perception of itself. The play is ultimately a reaction against the modern denial of values, and an affirmation that something inherent within us makes us human, and allows us to maintain faith in goodness and beauty. # Stoppard's first attempt to create historical drama was Travesties (1974), which uses as a starting point the coincidence that novelist James Joyce, Russian revolutionary Lenin, and Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara all lived in Zurich, Switzerland during World War I. No historical evidence indicates that the three ever encountered one another, but in Stoppard's imagination they do so. The text is complicated by the use of an elderly narrator, whose frazzled memory muddles details of plot beyond description. In the midst of the confusion, though, we may discern parallels between the goals of the artistic revolutionary and those of the political revolutionary, as well as the need for all individuals to establish a purpose for their existence. # These brief outlines suggest some of the themes that have buttressed Stoppard's extensive dramatic output. In more recent works, he has moved through a great range of political, social, religious, and scientific issues, many of which may be found in Arcadia, along with perspectives on Time, Poetry, Love, and other subjects too numerous to elucidate here. Perhaps the most important point to remember, though, is that no matter how intellectually daunting the material, Arcadia is, in fact, a "play," and that at its foundation lies a joy and creative energy to be found uniquely in the magic of theater. # II. Analysis of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Tom Stoppard's best-known and first major play, appeared initially as an amateur production in Edinburgh, Scotland, in August of 1966. Subsequent professional productions in London and New York in 1967 made Stoppard an international sensation and three decades and a number of major plays later Stoppard is now considered one of the most important playwrights in the latter half of the twentieth century. # Recognized still today as a consistently clever and daring comic playwright, Stoppard startled and captivated audiences for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead when he retold the story of Shakespeare's Hamlet as an absurdist-like farce, focusing on the point of view of two of the famous play's most insignificant characters. In Shakespeare's play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are little more than plot devices, school chums summoned by King Claudius to probe Hamlet's bizarre behavior at court and then ordered to escort Hamlet to England (and his execution) after Hamlet mistakenly kills Polonius. Hamlet escapes Claudius's plot and engineers instead the executions of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, whose deaths are reported incidentally after Hamlet returns to Denmark. In Stoppard's play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern become the major characters while the Hamlet figures become plot devices, and Stoppard's wildly comic play becomes the story of two ordinary men caught up in events they could neither understand nor control. Stoppard's play immediately invited comparisons with Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot and also brought to mind George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, and Luigi Pirandello. "Stoppardian" is now a recognizable epithet that suggests extraordinary verbal wit and the comic treatment of philosophical issues in often bizarre theatrical contexts. # Themes of the Play 1. Language and Communication In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, the two title characters often play with words. They pun off of each other's words without much intention of moving their dialogue toward a set purpose. Instead, they are simply goofing around, like two kids throwing a ball back and forth. At the same time, however, the consistently poor communication in the play seems to hint at a broader breakdown in understanding between the characters that may help send the play into its tragic spiral. Language is sometimes seen as an empowering way of writing one's own fate, but for Ros and Guil it often seems like an impotent tool, best suited for idle speculation. # 2. Isolation In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, main characters Ros and Guil, when left alone in the play, often suffer from feelings of isolation. In the opening and closing scenes of the play, it is just Ros and Guil alone on stage. One wonders if it is the degree to which these two are isolated that has led to their constant idleness and passivity, or if things worked the other way around. From the very start of the play, however, it does seem as if Ros and Guil are marked, as if they are moving toward their deaths, simply passing through the action of the play. The sense of isolation reaches its highest pitch, perhaps, when it is just the two of them in the dark on the boat in the last act. It is, in a sense, a premonition of death, or a fear of what death might be: bodiless nothingness, with only the mind working. # 3. Manipulation(操纵) People use each other quite a bit in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, and part of the reason the main characters, Ros and Guil, are never in control of their situation is because they seem naively incapable of using the people around them. Manipulation, in many ways, is compared the act of directing a play – it's the ability to control the course of events. A play is explored as something that manipulates the audience: something that attempts to affect the way that they think and feel. # 4. Fear In the opening of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, there is a long string of coin flips that come up heads, which frightens Guil, one of the main characters. He later attempts to reason through how the laws of probability could seemingly be suspended, and at one point concludes, "The scientific approach to the examination of phenomena is a defence against the pure emotion of fear" (1.73). What Guil means is that we fear the unknown (such as death). Science, by trying to make things comprehensible, attempts to reduce this fear. By coming to know things about our world and the laws by which it works, we try to feel more at home in it, more like we have a handle on what is happening. The alternative – recognizing just how little we know about the world around us – causes fear. # 5. Foolishness and Folly In many ways, in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead it is the title characters' fault that they die. They are easily, and, at times, willingly manipulated. Not to mention, Ros and Guil spend a good portion of the play messing around – swapping names, misunderstanding each other, playing at games of their own devising. Their foolishness is, in part, a source of comedy, but it also seems a natural way to stay entertained when one has as little to do. # 6. Passivity Ros and Guil may be at the center of the action in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, but they certainly don't drive it. It can be seen most clearly in Act II how they are just left to sit around and wait unless someone else crosses the stage or tells them what to do. Another main character, the Player, seems to suggest that they should be more active and that Guil shouldn't waste so much time questioning things, but Guil is less concerned with action than with freedom of action. Yet, in the end, the fact that Ros and Guil betray their friend Hamlet makes their passivity morally significant; their failure to act may play a role in their own fates. # 7. Versions of Reality In Shakespeare's Hamlet, the play-within-a-play is packed within a clear context and is used by Hamlet to send a message to Claudius. For us as the audience of Stoppard's play, however, the distinctions between a play and reality get totally jumbled. First, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern is nothing but a play on the stage. Secondly, it is a play that interacts with the action of an earlier play, Shakespeare's Hamlet. Third, it is unclear to what extent the Player and his Tragedians are driving the action of the play and to what extent the "real" characters are in control of what is happening. The difference between drama and reality is called into question, most explicitly in the arguments between Guil and the Player. # 8. Fate and Free Will This theme is introduced in the very first scene of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, where the long string of coins tosses coming up "heads" seems to suggest that the laws of probability have been suspended. The way that fate operates in the play is largely through the words of William Shakespeare. Since Stoppard's play works within the framework of Shakespeare's Hamlet, his characters are bound to undergo a certain series of events – their fate was "written" in 1600. Main characters Guil and Ros have the most freedom when they manage to get out of the action of the Hamlet storyline, but in these times they often find themselves bored and listless. The relationship between Stoppard's play and Shakespeare's allows Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead to ask the question: to what degree do fate and chance control our own lives? # 9. Morality So, you probably noticed that the word "dead" in the title Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, and that there is a lot of discussion of death in the play. Stoppard's play is intensely aware of the fact that we will all, one day, die. It is also aware of the fact that death simply cannot be captured in art. The main character, Guil, sees death as the negative, as a blind spot in the mind – something that humans are incapable of thinking about. As a result, he sees acted out deaths in plays as pretense – claiming to put something on stage that one cannot. In contrast, Guil's rival, the Player, thinks that no one can tell the difference between an acted death and a real one, and he thus decides to give his audiences the sort of entertainment they want – death, and lots of it. # Shakespeare in Love Written by Tom Stoppard