Chapters 7 and 8 Lecture

advertisement

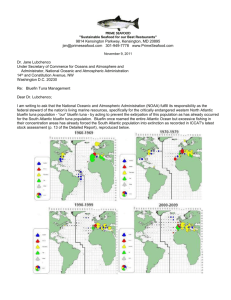

TUNA TALES TUNA I The World’s Tuna Fisheries TUNA II A Fishery Management Case Study: Yellowfin Tuna and Dolphins in the Eastern Tropical Pacific TUNA III The Mighty Bluefin Table 7.1. Principal species of tuna involved in commercial fishing Common name Scientific name Albacore Thunnus alalunga Bigeye Thunnus obesus Skipjack Katsuwonus pelamis Yellowfin Thunnus aobacares Atlantic bluefin Thunnus thynnus Pacific bluefin Thunnus orientalis Southern bluefin Thunnus maccoyii General Comments About Tuna Tuna are neither warm blooded nor cold blooded. Their circulatory system allows them to maintain their body temperature higher than their surroundings, but they cannot maintain a constant body temperature. The principal factors limiting the distribution of tuna are temperature and oxygen concentration. Because of their high metabolic rates, tuna are voracious predators. Daily food consumption can be as high as 25-30% of their body weight. Tuna are known to undertake very long migrations. Migrations across entire ocean basins are not unusual. To some extent tuna may use ocean currents to guide them on these migrations, but they also appear to have a geomagnetic sense. Skipjack, yellowfin, and bigeye tuna are generally considered to be tropical tunas. Albacore and bluefin tuna are found in more temperate latitudes Some things to think about Tuna enjoy: The eastern sides of ocean basins have: Warm Water Shallow Thermocline Lots of Oxygen Shallow Oxygen Zone Lots of Food Nutrient-Rich Upwelling Zones Some things to think about Tuna enjoy: The eastern sides of ocean basins have: Warm Water Shallow Thermocline Lots of Oxygen Shallow Oxygen Zone Lots of Food Nutrient-Rich Upwelling Zones Along the west coasts of continents tuna can be found: In Higher Concentrations In Shallower Water Closer to Shore For Easier Fishing Table 7.2. Pertinent information on commercially important tuna species Species Length (cm) Weight (kg) Age of sexual maturity (years) Lifespan (years) Albacore 60-90 10-20 5 10 Bigeye 80-180 15-20 4 10 Skipjack 30-80 8-10 2 12 Yellowfin 40-180 5-20 3 10 Atlantic bluefin 45-450 135-680 4-8 15-30 Pacific bluefin 150-300 300-555 6 30 200 200 8-12 40 Southern bluefin Table 7.2. Pertinent information on commercially important tuna species Species Length (cm) Weight (kg) Age of sexual maturity (years) Lifespan (years) Albacore 60-90 10-20 5 10 Bigeye 80-180 15-20 4 10 Skipjack 30-80 8-10 2 12 Yellowfin 40-180 5-20 3 10 Atlantic bluefin 45-450 135-680 4-8 15-30 Pacific bluefin 150-300 300-555 6 30 200 200 8-12 40 Southern bluefin Table 7.2. Pertinent information on commercially important tuna species Species Length (cm) Weight (kg) Age of sexual maturity (years) Lifespan (years) Albacore 60-90 10-20 5 10 Bigeye 80-180 15-20 4 10 Skipjack 30-80 8-10 2 12 Yellowfin 40-180 5-20 3 10 Atlantic bluefin 45-450 135-680 4-8 15-30 Pacific bluefin 150-300 300-555 6 30 200 200 8-12 40 Southern bluefin Table 7.2. Pertinent information on commercially important tuna species Species Length (cm) Weight (kg) Age of sexual maturity (years) Lifespan (years) Albacore 60-90 10-20 5 10 Bigeye 80-180 15-20 4 10 Skipjack 30-80 8-10 2 12 Yellowfin 40-180 5-20 3 10 Atlantic bluefin 45-450 135-680 4-8 15-30 Pacific bluefin 150-300 300-555 6 30 200 200 8-12 40 Southern bluefin Commercial catches of skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye, and albacore tuna Skipjack tuna Skipjack information Virtually the entire catch occurs in the Pacific (70%) and Indian (24%) oceans. The western Pacific accounts for 50% of the catch. Skipjack are the smallest of the commercially important tunas and have the largest surface-to-volume ratio. This makes thermoregulation more difficult for skipjack than the other tuna species. Temperature range is 20-30oC. Skipjack are also unique among the tunas in that the adults have no swim bladder. Hence they must expend more energy in routine swimming. Skipjack information Skipjack have a definite tendency to school, and most skipjack are caught with purse seines. FADs have been a major impetus to the skipjack fishery in the western Pacific. Diet includes clupeids, crustaceans, and mollusks, but may also include other skipjack. Peaks in foraging occur around dawn and dusk. Predators on skipjack tuna include sharks, billfish, wahoo, yellowfin tuna, and, in the case of small skipjack, even seabirds. Spawning occurs throughout the year in tropical latitudes but is confined to the summer months at higher latitudes. Major market for skipjack tuna is canned tuna – “light-meat” tuna. Skipjack information Skipjack have a definite tendency to school, and most skipjack are caught with purse seines. FADs have been a major impetus to the skipjack fishery in the western Pacific. Skipjack information Skipjack have a definite tendency to school, and most skipjack are caught with purse seines. FADs have been a major impetus to the skipjack fishery in the western Pacific. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/20/time-to-boycott-tuna-again/?scp=2&sq=tuna&st=cse FADs with location and biomass sensors Purse Seines targeting Skipjack Tuna Estimates of up to 20% of haul as bycatch Much of that bycatch is immature Yellowfin and Bigeye Fishing is done in unregulated “pockets” just outside the EEZs of Pacific Island nations Skipjack information Skipjack have a definite tendency to school, and most skipjack are caught with purse seines. FADs have been a major impetus to the skipjack fishery in the western Pacific. FAO Skipjack Tuna Catch Data Table 7.3. Principal nations contributing to the catch of skipjack tuna in 2002. Country Principal fishing area(s) % of catch Japan Northwest and west central Pacific 13.6 Indonesia West central Pacific and eastern Indian 11.7 Taiwan West central Pacific 11.5 South Korea West central Pacific 8.6 Spain Western Indian and east central Atlantic 6.9 Maldives Western Indian 5.7 Philippines West central Pacific 5.4 United States West central Pacific 4.4 Yellowfin tuna Yellowfin information Geographical distribution, temperature range, and spawning behavior very similar to skipjack. Tend to associate with dolphins more than any other species. Yellowfin have a keen sense of smell: dolphins have none. However, dolphins can track prey using ultrasonic echolocation. Pacific (67%) and Indian Ocean (22%) account for most of the catch. Much of the fishing is done with purse seines. Canned tuna (light tuna) is again the primary market. Table 7.4. Principal nations contributing to the catch of yellowfin tuna in 2002. Country Principal fishing area(s) % of catch Mexico East central Pacific 11.1 Indonesia West central Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean 10.6 Venezuela East central Pacific and southeastern Pacific 9.6 Philippines West central Pacific 7.5 Japan West central and northwest Pacific, western Indian Ocean 7.4 Taiwan West central Pacific and western Indian Ocean 7.2 Spain Western Indian Ocean and east central Atlantic 6.7 France Western Indian Ocean and east central Atlantic 5.1 Bigeye tuna Bigeye information Similar in appearance to yellowfin, but swim at greater depths and have a higher fat content. Catch distributed as follows: Pacific (50%), Indian (30%), Atlantic (20%). Small bigeye are caught as bycatch of purse seining for skipjack and yellowfin. The larger and more valuable bigeye are taken with long lines. The meat of bigeye tuna turns light grey and sometimes darkish after cooking or grilling, a characteristic that makes it less suited for canning than skipjack, yellowfin, or albacore tuna. By far the most popular market forms for bigeye tuna are fresh fillets (sashimi) and fresh whole fish. The principal market is Japan, where bigeye sashimi is in high demand. The principal fishing nations are Japan and Taiwan. Not a great deal is known about the ecology of bigeye tuna, and scientists do not agree on whether the stocks are being fully exploited. The bycatch of bigeye associated with the skipjack and yellowfin fisheries is a concern, since the fish in question are not sexually mature. Table 7.5. Principal nations contributing to the catch of bigeye tuna in 2002. Country Principal fishing area(s) % of catch Taiwan Indian Ocean, west central Pacific, southeastern Atlantic 24.2 Japan Indian Ocean, central and southeastern Pacific 23.7 South Korea East central Pacific 7.4 Spain Western Indian Ocean, east central Atlantic 7.0 Ecuador Southeastern Pacific 4.9 Indonesia Eastern Indian Ocean 4.9 China East central Pacific 4.3 USA East central Pacific 2.9 FAO Bigeye Tuna Catch Data Table 7.2. Pertinent information on commercially important tuna species Species Length (cm) Weight (kg) Age of sexual maturity (years) Lifespan (years) Albacore 60-90 10-20 5 10 Bigeye 80-180 15-20 4 10 Skipjack 30-80 8-10 2 12 Yellowfin 40-180 5-20 3 10 Atlantic bluefin 45-450 135-680 4-8 15-30 Pacific bluefin 150-300 300-555 6 30 200 200 8-12 40 Southern bluefin Albacore tuna Albacore information Albacore is a temperate water fish, and stocks in the northern and southern hemisphere are disjoint. In the northeastern Pacific, for example, albacore are not found in water with a temperature greater than 19oC. The principal fishing areas are the western and central Pacific, which together account for 58% of the catch. Almost all albacore are caught either with pole-and-line, surface trolling, or long lines. There is no purse seine fishery for albacore. The principal market for albacore is canned tuna. Albacore is the only canned tuna marketed as “white tuna”. Due to its unusual bone structure and the soft consistency of its meat, albacore cannot be filleted. As in the case of bigeye, Japan and Taiwan dominate the catch. FAO Albacore Catch Data Table 7.6. Principal nations contributing to the catch of albacore tuna in 2002. Country Principal fishing area(s) % of catch Japan Northwest and west central Pacific 28.8 Taiwan Southwest and central Pacific, southwest and west central Atlantic, western Indian Ocean 24.6 USA Northeast and southwest Pacific 7.4 Spain Northeast Atlantic 4.5 Fiji West central Pacific 3.4 South Africa Southeast Atlantic 2.8 American Samoa East central Pacific 2.5 New Zealand Southwest Pacific 2.4 Bluefin tuna Bluefin tuna being readied for auction at Tokyo’s Tsukiji Fish Market. Commercial catches of bluefin tuna species Atlantic bluefin information Atlantic bluefin are found only in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean and Black Sea. Bluefin in the South Atlantic are southern bluefin. Atlantic bluefin are the largest of the tunas, with weights up to 680 kg and a lifespan up to 30 years. The fishery for Atlantic bluefin goes back literally thousands of years. There are two spawning areas, one in the Gulf of Mexico between midApril and mid-June, and the second in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas from June through August. There is controversy over whether the stocks should be considered separate or not. Tagging studies have shown that the tuna definitely make trans-Atlantic migrations. Atlantic bluefin dive to depths of as much as 1,000 meters and feed on fish such as mackerel, herring whiting, and squid. The commercial value of Atlantic bluefin prior to 1970 was about $0.10 per kg. Increasing demand for giant bluefin to supply the Japanese sushi and sashimi markets changed this picture dramatically. With the development of air freight in the early 1970s, giant Atlantic bluefin were being caught and immediately shipped to Japan, where they were sold for more than $2 per kg. n. b., Current prices are $20-$70 per kilogram. Management International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) formed in 1969. Western Atlantic stock of bluefin tuna continued to decline, and in 1981 ICCAT set a quota of 1,160 tonnes for the western Atlantic. This is based on the assumption by ICCAT that there were two separate stocks – western and eastern Atlantic. The commercial value of Atlantic bluefin prior to 1970 was about $0.10 per kg. Increasing demand for giant bluefin to supply the Japanese sushi and sashimi markets changed this picture dramatically. With the development of air freight in the early 1970s, giant Atlantic bluefin were being caught and immediately shipped to Japan, where they were sold for more than $2 per kg. n. b., Current prices are $20-$70 per kilogram. Management International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) formed in 1969. Western Atlantic stock of bluefin tuna continued to decline, and in 1981 ICCAT set a quota of 1,160 tonnes for the western Atlantic. This is based on the assumption by ICCAT that there were two separate stocks – western and eastern Atlantic. Since 1982 the annual catches of bluefin tuna from the western Atlantic have fluctuated around an average of about 2,200 tonnes. During the same time catches of bluefin in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean increased to roughly 40,000 tonnes, with most of the catch coming from the Mediterranean Sea. By the early 1990s the western Atlantic bluefin stock had declined by about a factor of 10 from its level in 1975, and by 1993 the eastern Atlantic population was estimated to be only 13% of its size in 1970. Efforts by several countries (Sweden, Kenya) to list the western Atlantic bluefin population in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Proposals withdrawn as result of pressure from Japan. About 65% of the catch currently comes from the Mediterranean. Atlantic bluefin are taken using pole-and-line, surface trolling, and long lines. Table 7.7. Principal nations contributing to the catch of Atlantic bluefin tuna in 2002. Country Principal fishing area(s) % of catch France Mediterranean 18.7 Spain Northeast Atlantic, Mediterranean 17.9 Italy Mediterranean 13.2 Japan Northeast Atlantic 10.0 Morocco East central Atlantic 8.5 Tunisia Mediterranean 7.2 Turkey Mediterranean 6.5 Algeria Mediterranean 4.9 United States Northwest Atlantic 3.4 Restrictions on fishing have apparently stopped the decline of the western Atlantic bluefin stock in recent years. However, the stock is either not recovering or is recovering very slowly. At its 1998 meeting, ICCAT adopted a rebuilding program for the western stock with a goal of reaching the maximum sustainable yield in 20 years. The total allowable catch (TAC) in the western Atlantic is currently 2,700 tonnes, with about 55% of that quota being allocated to the United States. In the Mediterranean, about 30% of the catches in 1993 were below the minimum size limit, an indication that the nations involved in the fishery were not adhering to ICCAT recommendations. Scientific evidence indicates that the catch in the eastern Atlantic/Mediterranean must be reduced to no more than 25,000 tonnes before the stock can begin rebuilding. The reported catch in the eastern Atlantic/Mediterranean in 2002 was a little less than 33,000 tonnes. Atlantic Bluefin: Enough Already http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/mar2008/2008-03-20-01.asp http://panda.org/about_wwf/where_we_work/europe/what_we_do/ mediterranean/about/marine/bluefin_tuna/bluefin_tuna_news/ index.cfm?uNewsID=126820 http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2007/09/19/europe/ EU-GEN-EU-Bluefin-Tuna.php http://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/19/ ready-for-life-without-bluefin-tuna/ Pacific bluefin information The Pacific bluefin fishery is the only unregulated bluefin fishery in the world. Japan currently accounts for about 64% of the catch, virtually all of which is taken in the northwest Pacific. Taiwan (west central Pacific and northwest Pacific) and Mexico (east central Pacific), account for the remainder of the catch. Unlike the Atlantic bluefin, there is clearly only one stock of Pacific bluefin tuna. Adults are known to spawn between the Philippines and southern Japan and in the Sea of Japan during the spring and summer. Tagging studies indicate that some Pacific bluefin remain in the western Pacific for their entire lives. Others migrate to the eastern Pacific, mostly during the first and second years of life, and remain there for 1-2 years. Pacific bluefin are caught on a variety of gear, and some are taken as bycatch of longlines targeting tropical tuna. The fish caught using surface gear are often juveniles, i.e., sexually immature. Almost all Pacific bluefin taken in the eastern Pacific are sexually immature. Japanese catch Pacific bluefin less than one year old by trolling. The fish are 15-30 cm in length. Caught in warm, shallow water in the eastern Pacific, using purse seines. Caught by trolling and longlines in other areas Theoretical studies indicate that yield per recruit would be maximized if Pacific bluefin were not recruited to the fishery until age 3-5. Southern bluefin information Southern bluefin are the most overexploited of the bluefin tuna. There is only one known breeding ground, in the Indian Ocean southeast of Java, Indonesia. Juveniles migrate down the west coast of Australia. They may spend the first few summers of their life in surface waters off the south coast of Australia, but during the winter they move into deeper, temperate oceanic waters. The fishery is dominated by Japan and Australia. As is the case with other bluefin species, surface gear takes many sexually immature fish. Table 7.8. Principal nations contributing to the catch of Southern bluefin tuna in 2002. Country Principal fishing area(s) % of catch Japan Indian Ocean, Pacific southwest, Atlantic southeast 38.2 Australia Indian Ocean eastern 34.8 Indonesia Indian Ocean eastern 9.7 Taiwan Indian Ocean 7.2 South Korea Indian Ocean 4.3 New Zealand Pacific southwest 3.0 Since about 1990 a fishery has developed off the coast of South Australia for juvenile fish that are transferred to floating enclosures and fattened to increase their market value. Initially these farmed fish were caught with pole-and-line, but they are now taken with purse seines. The fish are transferred to floating pens, which are towed to Port Lincoln (South Australia). From there the tuna are transferred to moored farm pens. In recent years 60-70% of the global catch of southern bluefin tuna has been longlined. The recruitment of young fish declined substantially after 1980, and fisheries biologists agree that the stock has been the victim of recruitment overfishing since that time. Current estimates indicate that the spawning stock biomass is roughly 7-15% of the level in 1960 (when substantial reductions had already occurred). Recognizing that the southern bluefin stock was in trouble, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand set informal catch quotas from 1989 to 1993, with Australia allocated 5,265 tonnes, Japan 6,065 tonnes, and New Zealand 420 tonnes. The three countries signed an international convention in 1993 called the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) After 1994, the catch quotas were allocated by the CCSBT. South Korea and Taiwan joined the CCSBT in 2001 and 2002, respectively, and Indonesia has become a cooperating non-member. Under current management there is no evidence that the spawning stock is recovering. The initial goal of the CCSBT was to rebuild the spawning stock to the 1980 level by 2010, but that target has now been pushed back to 2020. However, Australian and New Zealand scientists give the CCSBT little chance of achieving that goal and feel that further reductions in the catch quotas will be needed to give the stock a chance to recover. The long time to reach sexual maturity makes this species particularly vulnerable to overfishing. TUNA TALES TUNA I The World’s Tuna Fisheries TUNA II A Fishery Management Case Study: Yellowfin Tuna and Dolphins in the Eastern Tropical Pacific TUNA III The Mighty Bluefin Management Western Pacific - Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. First meeting of the group in December, 2004. Indian Ocean - Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC). Agreement came into force in March 1997. Member nations who object to a decision by the IOTC are not bound by it. Eastern Pacific – Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC). Originally (1950) USA and Costa Rica. Now 12 nations. Principal focus is yellowfin tuna. Management Western Pacific - Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. First meeting of the group in December, 2004. Indian Ocean - Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC). Agreement came into force in March 1997. Member nations who object to a decision by the IOTC are not bound by it. Eastern Pacific – Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC). Originally (1950) USA and Costa Rica. Now 12 nations. Principal focus is yellowfin tuna. Management: IATTC and CYRA Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC). Formed in 1950 by USA and Costa Rica. Now includes 12 countries. Purview is eastern tropical Pacific to 140o west longitude. Management has been almost entirely concerned with yellowfin tuna. Commission’s Yellowfin Regulatory Area (CYRA) is de facto where the ITTAC is regulating tuna catches Geographical extent of the CYRA. Principal species of tuna involved in commercial fishing Common name Scientific name Albacore Thunnus alalunga Bigeye Thunnus obesus Skipjack Katsuwonus pelamis Yellowfin Thunnus aobacares Atlantic bluefin Thunnus thynnus Pacific bluefin Thunnus orientalis Southern bluefin Thunnus maccoyii Yellowfin tuna Commercial catches of yellowfin tuna Background information on the tuna/dolphin problem Problem is confined to the eastern tropical Pacific, where yellowfin tuna tend to congregate under schools of certain species of dolphins For many years fishing was done by chumming (pole and line) with no impact on dolphins Purse seining phased in during last few years of 1950s Combination of fishing tuna located under schools of dolphins proved deadly to dolphins and damaging to tuna stocks Tuna can be found by several methods. “Porpoise” sets actually account for less than half the purse seine sets during the 1970s. Log sets a common alternative Key strategies for releasing dolphins from net include backing down procedure (1960) and Medina panels (1971) A log used by tuna fishermen to attract schools of tuna A floating board that has attracted some small fish QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. TUNA - DOLPHIN ASSOCIATION TUNA These animals have a sense of smell that works in the water They are not known to be echo-locators DOLPHINS Their olfactory sense is not designed to work in the water They have excellent sonar abilities Might their combined sensory capabilities be mutually beneficial? Tuna boat in process of setting purse seine Final stages of setting the purse seine Tuna boat with purse seine encircling school of dolphins Schematic Depiction of a “Porpoise Set” Tuna caught in purse seine Beginning job of removing tuna from purse seine with brail net Schematic Depiction of a “Porpoise Set” Initial stages of backing down operation Dolphins escaping from purse seine during backing down operation Dolphins escaped from tuna net Schematic Depiction of a “Porpoise Set” Marine Mammal Protection Act – 1972 “Certain species and population stocks of marine mammals are, or may be, in danger of extinction or depletion as a result of man’s activities . . . . They should not be permitted to diminish below their optimum sustainable population . . . . Measures should be immediately taken to replenish any species or population stock which has already diminished below [its optimum sustainable] population.” “In any event it shall be the immediate goal that the incidental kill or incidental serious injury of marine mammals permitted in the course of commercial fishing operations be reduced to insignificant levels approaching a zero mortality and serious injury rate.” NMFS permits voided by Judge Richey on grounds that NMFS had inadequate information on which to base kill quotas First and second status of porpoise workshops – 1976 and 1979 Optimum sustainable population defined to be any stock size between 65% and 80% of the virgin stock NMFS Implementation of MMPA with respect to dolphin stocks Determination of numbers of dolphins in various stocks (1976-1979) Use of virtual population analysis to estimate size of virgin stocks (assumed to be size of stocks in 1959) Two stocks appear to be well below the OSP – eastern spinner and northern offshore spotted Sets on eastern spinners prohibited. 90% of subsequent sets are on spotted dolphins Judge Richey approves NMFS permits. Quotas steadily decline with time Table 8.1. Status of dolphin stocks in the eastern tropical Pacifi c as of 1979 estim ated by virtual population analysis Stock % of unexploited population Coastal spott ed 97-100 Northern offshore spott ed 34-55 Southern offshore spott ed 93-98 Eastern spinner 16-21 Northern whitebell y spinner 62-81 Southern whitebelly spinner 85-94 Baja neritic and northern common 95-100 Central tropical common 74-99 Central tropical striped 99-100 Subsequent developments Early 1980s – U.S. wants to put observers on all tuna boats. Observers on fewer than 50% of U.S. boats and only a handful of foreign boat-trips. Early 1980s – U.S. wants to ban sundown sets Tuna boats start to drop out of U.S. fleet – 155 in 1976, 34 in 1987, 29 in 1990, 3 in 1991. Late 1980s – dolphin kills start to increase 1988 Amendments to the MMPA Must be 100% observer coverage of U.S.-registered boats With some exceptions, U.S. boats cannot use sundown sets Nations intending to export tuna to the United States must do the following: have a regulatory program comparable to that of the U.S. (no sundown sets) dolphin mortality must be no more than 1.25 the U.S. rate no more than 15% of kill can be eastern spinners participate in IATTC observer program submit annual report concerning performance To avoid laundering of tuna Any nation exporting yellowfin tuna to the U.S. must identify the harvesting nation Such exporters must ban the entry of yellowfin tuna from any nation that the U.S. embargoes Sanctions will be imposed if harvesting and exporting nations fail to comply with these requirements within six months. Dolphin-safe tuna 1990 – Dolphin Protection Consumer Information Act establishes standards for “dolphin-safe” April 12, 1990 – Star-Kist, Bumble Bee, and Chicken of the Sea announce that they will not buy tuna caught using porpoise sets 1991 – U.S. embargoes challenged by Mexico – General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Reported dolphin mortalities continue to drop. Kill has been less than 2,000 animals per year since 1998 1997 – International Dolphin Conservation Program Act – amends certain provisions of the MMPA. Secretary of Commerce to make final finding concerning the dolphinsafe label and the impact of the fishery on dolphin stocks by 12/31/02. 12/31/02 – NMFS rules that use of porpoise sets is having “no significant adverse impact on dolphin populations in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean.” This finding effectively changes the definition of dolphin-safe to include tuna caught with porpoise sets as long as no dolphins were killed or seriously injured. Table 8.2. Current estimates of status of depleted dolphin stocks. Source: NMFS Stock Estimated population in 2000 % of virgin stock size Northeastern offshore spotted 641,153 20% Eastern spinner 448,608 35% Lessons Learned? Pluses Consumers, via their government, pushed effectively for the implementation of management Benefits to the fishery from accepting the management plan 1. Main markets didn’t want to buy dead dolphin 2. Spared dolphins live to help find tuna again Minuses Expenses to the industry have forced much of the fishing fleet to jurisdictions where the management plan can be evaded A Tuna Management Case Study: Good Idea, Poor Execution, and a Little Bit of Luck Goal of management has been to keep catch per unit effort above 2.7 tonnes per fishing day. Problems associated with projecting the time when the quota would be reached has often resulted in catches exceeding quotas. Poor judgement used in adjusting quotas. Regime shift favoring yellowfin tuna seems to have occurred in 1983-1985. There were very good recruitment years in 1998-2000. Catch (tonnes) Goal of management has been to keep catch per unit effort above 2.7 tonnes per fishing day and to base a given year’s quota largely on whether the preceding year’s quota resulted in an increase or decrease in the CPUE. 2.7 tonnes of catch 1 day of effort (Days) A Tuna Management Case Study: Good Idea, Poor Execution, and a Little Bit of Luck A Pacific Basin Regime Shift and some following good recruitment years did more good than the management efforts in this case. Think what would have happened to this fishery had the regime shift not been a beneficial one! TUNA TALES TUNA I The World’s Tuna Fisheries TUNA II A Fishery Management Case Study: Yellowfin Tuna and Dolphins in the Eastern Tropical Pacific TUNA III The Mighty Bluefin ATLANTIC BLUEFIN THUNNUS THYNNUS Early History: Caught in Mediterranean coastal fisheries, using artisanal techniques Π (Hand lines, and coastal traps, nets and pounds) A little more recently: ~1900 to ~1960. Sport fishing, off the Atlantic coasts of Canada and the U.S. A Nova Scotia tournament recorded a peak landingof 1,760 fish in 1949. Fish caught in tournaments were sold to pet food companies for pennies a pound. And then starting in the 1960s and 1970s: Japanese demand for high-fat tuna; The availability of airfreighting from the Atlantic to Japan; Made recreationally-caught Atlantic Bluefin worth many dollars a pound. Heavily capitali zed commercial fisheries for Atlantic Bluefin we re developed. These targeted both g iant adults (caught by hook and line for sh ipment to Japan) AND, small schooling bluefin (caught by purse sei ne, for canning). As values rose, purse seine technology was applied to large Bluefins. International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) Established in 1966 Two-Stock Hypothesis: A Western Stock, spawning in the Gulf of Mexico; An Eastern Stock, spawning in the Mediterranean and the Adriatic. Western Stock much smaller than the Eastern Stock. The stocks donΥtmix. Management Based on the TwoStock Hypothesis (1970s Π1990s): Stock Management divided at 45 degrees longitude, down the middle of the Atlantic. Management Based on the TwoStock Hypothesis (1970s Π1990s): Western Stock: reasonably wellmanaged, but stock continued to decline. Eastern Stock: not so well-managed, and numerous non-ICCAT nations in the fishery. Fishers of the Western Stock upset by the abuses of fishers of the Eastern Stock and press for increased quotas for themselves. Science, 1995-2005: Long term tagging study of Western Stock tuna Confirms the two-stock hypothesis, with respect to breeding Refutes the two-stock hypothesis with respect to feeding Science, 1995-2005: Western Stock fish cross the Atlantic, and vice-versa The poorly managed and poorly regulated European and African fisheries are wiping out the Western Stock. Science, 1995-2005: Western Stock fish cross the Atlantic, and vice-versa The poorly managed and poorly regulated European and African fisheries are wiping out the Western Stock. Western Stock Distribution Block et al., 2005 5 years of tracking data for Tuna #603 Block et al., 2005 THE FUTURE FOR ATLANTIC BLUEFIN CAPTURE FISHERIES: BLEAK FARMED FROM WILD STOCK: WEAK CLOSE THE LIFE CYCLE AND FARM: HARD WORK Nature, 2005 The Economist, 2009 ICCAT International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas The Current Situation: Vast Over-Capitalization in European and African fisheries. In 2008, catch potential of E&A fisheries - > 54,000 tonnes. In 2008, ICCAT catch limits of E&A fisheries Π28,500 tonnes. In 2008, fisheries scientists recommended catch - 15,000 tonnes. ICCAT International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas Also Known As International Conspiracy to Catch All Tunas A Note on the Pacific Bluefin Unlike the Atlantic bluefin, there is clearly only one stock of Pacific Bluefin tuna. Adults are known to spawn between the Philippines and southern Japan and in the Sea of Japan during the spring and summer. Tagging studies indicate that some Pacific bluefin remain in the western Pacific for their entire lives. Others migrate to the eastern Pacific, mostly during the first and second years of life, and remain there for 1-2 years. Pacific bluefin are caught on a variety of gear, and some are taken as bycatch of longlines targeting tropical tuna. The fish caught using surface gear are often juveniles, i.e., sexually immature. Almost all Pacific bluefin taken in the eastern Pacific are sexually immature. Japanese catch Pacific bluefin less than one year old by trolling. The fish are 15-30 cm in length. Caught in warm, shallow water in the eastern Pacific, using purse seines. Caught by trolling and longlines in other areas Theoretical studies indicate that yield per recruit would be maximized if Pacific bluefin were not recruited to the fishery until age 3-5.