Sonnet information

advertisement

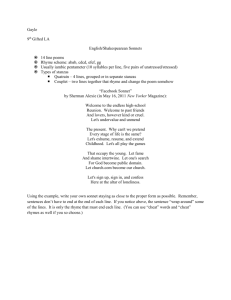

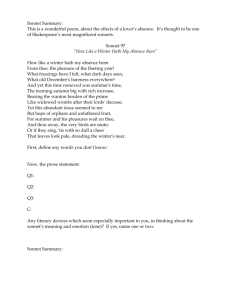

THE SONNET In modern usage the word sonnet refers to a fourteen-line poem written in iambic pentameter (each line contains ten syllables, five of which are usually stressed). The word sonnet comes from the Italian sonetto, which means “little sound” or “little song.” The sonnet originated in Italy in the thirteenth century. In the fourteenth century Petrarch produced what was to become the most important group of sonnets in European literature. His great sequence of 366 lyrics, containing 317 true sonnets, is addressed to a woman named Laura, whom Petrarch loved but with whom he was never able to establish a close relationship. Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Petrarch remained the dominant influence in Renaissance lyric poetry, particularly in the sonnet. The Italian sonnet was introduced into English poetry by Wyatt. His contemporary Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, was also an innovative sonnet writer in the time of Henry VIII. The sonnets of Wyatt and Surrey were widely known to later sixteenth-century poets through a collection published in 1557 called Tottel’s Miscellany. During the Elizabethan period the sonnet really came into its own. Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella, the first great sonnet sequence in English, was written about 1582 and published in 1591. It started a vogue which continued right through to the end of the century. Producing a sonnet cycle became the fashionable thing to do for an aspiring writer. Other important Elizabethan sonnet cycles were written by Fulke Greville, Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, Spenser, and Shakespeare. The central theme in these sonnet cycles was the love of the poet for a beautiful but unattainable woman. Long-established and, by today’s standards, sexist convention governed their relationship. She was the “cruel fair” whose favors her servant sought endlessly but hopelessly. Her moods created the weather. A brightening glance, for example, was a good omen but not entirely trustworthy, because eyes as “rising suns” could change instantly to eyes as “stars,” in which case they were capable of emitting “angry sparks.” Then again, while the lady’s eyes were alternately suns or stars, her hair was almost invariably “gold wires”; her cheeks, “roses”; her lips, “cherries”; and her teeth, “orient pearls.” The love lyrics addressed to her were not necessarily addressed to a living person. It was small matter whether the lady did or did not exist in fact. Very often these love poems were addressed to a small circle of congenial spirits— fellow poets, wits, ladies of fashion—whom the poet wished to amuse. The way to impress this company was to exhibit special ingenuity in devising new variations on the old theme or in polishing one’s work to an impressively high gloss. The reproach that such poetry is “insincere” would have astonished any Elizabethan. The formal conventions, the rules of the sonnet game, were there with all the weighty authority of tradition behind them, and they were there to be followed. There are two main types of sonnets: The “Italian” or “Petrarchan” sonnet: this type of sonnet has a rhyme scheme which divides the poem into an octave (the first eight lines) and a sestet (the last six lines). Using letters of the alphabet to represent words that rhyme, the usual rhyme scheme of the octave may be represented as abbaabba. Sometimes the scheme is abababab. The sestet may rhyme in various ways: cdecde, for example, or cdcdcd. The shift from octave to sestet is often a point of dramatic change. We sometimes call this shift the turn or volta (an Italian word meaning “turn”). In the original Italian form, the sestet almost never ends with a rhyming pair, or couplet. But English poets, from Wyatt on through Sidney and John Donne, tend to prefer a final couplet. The “English” or “Shakespearean” sonnet: In this form the lines are organized into three groups of alternating rhymes plus a final couplet. The four-line groups are called quatrains. The rhyme scheme, then, is usually abab cdcd efef gg. Although this type of sonnet is often called “Shakespearean,” it was actually developed by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, many years before Shakespeare used it. A third type of sonnet, the “Spenserian” [sonnet], is less important historically than the Petrarchan and Shakespearean forms. But it is characteristic of Spenser to have invented his own sonnet form with complicated interlocking rhymes: abab bcbc cdcd ee. We may note the similarity to the nine-line stanza that Spenser invented for his epic poem, The Faerie Queene: ababbcbcc. All these facts about different sonnet forms are important only if they help us experience and talk about the meaning of specific poems. It may seem strange to us that Elizabethan writers would have wanted to express themselves in a form so strictly controlled and predetermined. But for the Elizabethans the intricate pattern of the sonnet had an intrinsic beauty, pleasurable to contemplate in the way that an abstract design in a piece of cloth or carpet is pleasurable to look at. They would also have valued the sonnet pattern as a challenge to their skill as poets. Most important, however, the Elizabethans would have thought of the formal demands of the sonnet not simply as restrictions or limitations, but as expressive resources—as structural features that give shape, emphasis, and organization to what is said. As readers, we need to be alert to these expressive resources of sonnet form. We should consider questions like the following: How does a poet use rhymes and rhyme scheme to reinforce what the poem says? How does a poet take advantage of the turn from octave to sestet, or the shift from one quatrain to another? How does the final couplet function? How do the patterns created by rhyme relate to other patterns created by grammar, word order, the positioning or grouping of images, or the movement of logical argument? When we learn to read with questions likes these in mind, sonnets become interesting because of, rather than in spite of, their strict form.