Food & Waste - SHARTHAK NEUPANE

FOOD & WASTE

2014 GHG Inventory for Colby-Sawyer College

DECEMBER 11, 2014

Jenisha Shrestha

Sharthak Neupane

Johann Graefe

Table of Contents

Colby-Sawyer College vs. ACUPCC Benchmark Colleges

.................................................................... 13

Free distribution of Reusable water mugs

...................................................................................... 24

Post-Consumer: Earth Tub Systems

................................................................................................ 27

Appendix A: Potential Hyper-Local Farms

.......................................................................................... 32

Farms with Black River Produce Partnership

................................................................................. 32

1

Other Local Farms Worth Considering.

........................................................................................... 36

Appendix C: Graphical representation of Benchmark College’s current emissions

Appendix D: Existing Locations of water fountains on-campus

........................................................ 40

2

Introduction

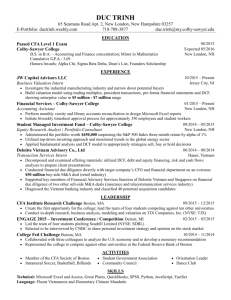

This report offers an in-depth analysis of Colby-Sawyer College’s current food and waste systems. It examines the production of organic food waste in the Sodexo

Dining Hall, assesses local food options made available to students, faculty, and staff, and inspects on-campus bottled water related issues.

Throughout this report, several regional colleges are used as benchmarks to develop recommendations for Colby-Sawyer. Recommendations offer insight of ways in which Colby-Sawyer can implement sustainable solutions to amend and improve current food and waste management practices. Specific recommendations involve diverting organic food waste from landfills, transitioning into a hyper-local food system, and banning the use of plastic water bottles. Recommendations must provide the college with viable solutions that are cost-effective and sustainable. Our group’s ultimate goal is to propose recommendations that advance the college’s strategic themes of Living Sustainably, Linking to the World, and Dynamic Devotion to Excellence.

Current Scenario

Food Input to the College

Colby-Sawyer College’s food operations is managed by Sodexo Dining Services with a strong commitment to health and happiness of our students, as well as whole systems sustainability. The Dining Services have demonstrated their commitment by preparing nutritious meals from scratch, promoting fair practices in food procurement and conserving resources. Sodexo’s own corporate goals outlined in their Better Tomorrow Plan (See Appendix A) also aligns with their efforts that helps Colby-Sawyer move towards the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050.

In April 2012, a student-led initiative to secure 20% of the food items offered in

Colby-Sawyer's dining hall from local sources sparked a successful partnership between students, college administrators and Sodexo Dining Services. The Petition, signed by 734 students stated as follows:

“In accordance with living sustainably and linking to the outside world as stated in the strategic themes, the purpose of this petition

3

is to enact a Colby-Sawyer College policy, which will amend that:

20% of all food served in the Colby-Sawyer dining hall will come from local sources.

Local is defined by this petition as 100 miles radius.

The policy to be implemented by beginning of fall semester 2013.”

Figure 1: 100 mile radius around

Colby-Sawyer College

After a year and a half of research and networking, the college finally achieved the goal of 20% local food by spring 2013. Today, the dining hall offers an average of 28% local food. Black River Produce, a Vermont-based distributor is the primary supplier for Sodexo at Colby-Sawyer. Black River Produce has helped us source most of our local products, including some meat products processed at their own plant, whenever possible. Although winter in the Northeast makes it hard to procure local produce, Colby-Sawyer uses what is available and meets the 20 percent goal by focusing on proteins. All of the pork and beef products, and 50 percent of the chicken come from local farms.

Some of the local farm supplying to Colby-Sawyer are as follows:

Baker's Dozen – Essex Junction, VT

Black River Produce – North Springfield,

VT

Carando Salami – Springfield, MA

Carla's Pasta – South Windsor, CT

Divine Line Foods – Exeter, NH

Gifford's Ice Cream – Skowhegan, ME

Gold Medal Bakery – Fall River, MA

Grandy Oats Granola – Brownfield, ME

HP Hood– Concord, NH

Joseph's Wraps – Lowell, MA

Koffee Kup Bakery – Burlington, VT

Maple Brook Fine Cheese – Bennington,

VT

Misty Knoll Farms – New Haven, VT

NorthCenter Foodservice Corp. – Augusta,

ME

Pete and Gerry's Organic Eggs – Monroe, NH

Figure 2: Location of Local Farms supplying to Colby-Sawyer (Map from Sodexo)

4

Stonyfield Yogurt – Londonderry, NH

Vermont Fresh Foods – Proctorville, VT

Vermont Soy – Hardwick, VT

Percentage of Local Food Input in the Dining Hall

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

13%

11%

12%

16%

17%

22%

30%

35%

29%

11%

22% 22%

Aug-13 Sep-13 Oct-13 Nov-13 Dec-13 Jan-14 Feb-14 Mar-14 Apr-14 May-14 Jun-14 Jul-14

Figure 3: Monthly Local Food Input to Colby-Sawyer College from August 2013-July 2014

There is a monthly variation in the percentage of local food sourced by

Sodexo, which is mainly due to the harsh winters in the Northeast region. In the month of May, we see a drastic drop in the local food purchase because the students leave for the summer break. So, Sodexo does not need to purchase any food for that month. However, overall there seems to be an increasing trend in the purchase of local foods by Sodexo.

Waste and Recycling

Since 2011, Colby-Sawyer College has contracted with Casella Waste

Management to provide campus wide zero-sort, single-stream recycling with the expectation that human hours spent sorting and wrangling with recyclables would decrease while the amount of materials recycled would increase due to the ease of tossing paper, cardboard, plastics, glass and metal into one bin. Figure 3 shows the total waste composition of Colby-Sawyer College for the past 3 fiscal years as determined by Casella Waste Management through their yearly trash audits.

5

Prior to 2014, Colby-Sawyer

College had partnered with local pig farms and vermi-composting farms for the organic waste disposal.

However, these partnership ceased due to the contamination in the food waste. Since 2014, Casella has been contracted with disposing our organic waste to the landfill. Landfill includes whatever was placed in the trash dumpsters during the period.

So, organics that weren't specifically diverted are also included in that landfill number.

The data for

250

200

150

100

50

0

450

Total Waste Composition at

Colby-Sawyer College

400

350

300

265,7

228,7

0

55,1

197,9

0

81,6

20,8

123,2

2012

Zero-Sort

2013

Organics

2014

Landfill

Figure 4: Waste and Recycling at Colby-Sawyer

College (Data from Casella, 2014) organic waste in 2014 as represented in Figure 3 does not

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

Recycling and Landfill Trends over Time

19,42

29,19

2013

81,6

197,9

29,19

31,68

2014

123,2

265,7

31,68

35

30

25

20

5

0

15

10

Zero-Sort

Landfill

%Recycled

2012

55,1

228,7

19,42

Figure 5: Annual Diversion Rate for Colby-Sawyer College (Data from Casella, 2014)

6

accurately capture the annual organic waste produced by the college as Casella was contracted half way through the fiscal year.

With the increase in the student population at Colby-Sawyer, the amount of waste and recycling generated has also been increasing gradually. From FY 2012 to

FY 2014, the annual waste diversion rate has increased from 19.42% to 31.6%. This increase in the recycling rate is mainly to the extensive recycling outreach program and the convenience of recycling throughout the campus.

If Colby-Sawyer did not recycle and sent everything to landfill, the college’s waste carbon footprint would have been 478 Metric Tons of CO

2

emission. Based on our current recycling practices, the college’s carbon footprint is much lower with the emission of 77 Metric Tons of CO

2

. This net benefit is equal to 79 cars off the road or 85 acres of pine forest planted.

Based on the lasted Trash Audit conducted on 11 November 2014, Colby's

Zero-Sort has about 17% plastic and 21% metal and 13% glass. Much of that is likely beverage containers. Tom Lantz, Service Consultant for Casella mentions “that approximately 25% of the trash/landfill load was "missed opportunity" for potentially recyclable material.” In FY2014, the amount of landfill has increased by

1/3 rd from FY 2013, most of which could have potentially been recycled. There seems to be more opportunities for Colby-Sawyer to expand their recycling efforts.

Vending Machine Sales

In order to better understand the single- use plastic bottled water on Colby-

Sawyer College, our group attempted to look at the yearly vending machine sales of the college. Our effort to make this study aligns with the college’s Climate action plan that pledges to reduce Greenhouse gas emission by 25% by 2015.

The college vending machine sales is contracted to Newmont

Vending Services, Claremont. The vending machine caters various types of single use bottled drinks like PowerAde, Iced tea and three different types of Soda. The college has two vending machines at all residence halls, two at Ware Student Campus,

Mercer Gym, Hogan Sports

Centre and Library. Figure 6

Total Annual Bottle sales from July

2013-June 2014: 21000

14000

7000

Number of Water bottles

Number of Soda bottles

Figure 6: Vending Machine Sales for FY 2014 (Data from Newmont Vending, 2014)

7

shows the annual sales made from 15 beverages vending machines inside the campus for the past year. Out of the total 29 vending machines inside the campus, the college makes an annual sales of 7,000 single use water bottles which is equivalent to (7000*$ 1.25)= $8750. It accounts for 33% of the total vending machine sales.

We looked at some benchmark colleges and found out that University of Vermont, which implemented Ban the plastic bottles in 2007, made annual sales of 1,037,000 single use beverage bottles from vending machines and retail out of which 20% was bottled water. (Office of Sustanability, 2012)

Organic Waste

Organic waste from the dining hall has been a significant issue in recent years.

While there have been many efforts to manage organic waste in the past, Colby-

Sawyer has been unable to come up with a permanent solution thus far. The most recent waste management practice was a partnership with local pig farmers, in which Colby-Sawyer provided participating farmers with food waste. The food waste was converted into pig feed and supplied to the pigs. Although this partnership allowed Colby-Sawyer to divert food waste from the landfill, the partnership did not prove to be long-lasting. This was the case, because the food waste was contaminated with utensils, which presented to be a choking hazard for the pigs. Consequently, the pig farmers chose to terminate the partnership.

Currently, food waste from the dining hall is being collected by Casella, and is sent directly to a landfill. When food is disposed in a landfill, it rots and becomes a significant source of methane. Methane, a potent greenhouse gas, has twenty-one times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. From an environmental standpoint, there is a pressing need to implement a more sustainable method in order to manage Colby-Sawyer’s food waste.

Pre-Consumer : 245 lbs./day Post Consumer: 229.3lbs./day

Dinner:

125 lbs.

or 51%

Breakfast:

45 lbs. or 18%

Lunch:

75 lbs. or

31%

Breakfas t: 44.6 lbs or …

Dinner: 113.7 lbs.

or 50%

Lunch: 71 lbs.

or 31%

8

Figure 7: Daily Food Waste from Dinning Hall (Data collected: 22 Oct 2014)

In terms of actual food waste production, Colby-Sawyer produces both preconsumer and post-consumer waste. Pre-consumer waste refers to the unusable materials (e.g. seeds, peels, etc.) generated by Sodexo during meal preparations.

Post-consumer waste refers to all fully-prepared foods and beverages (including meat and dairy) that are uneaten or disposed of by students/faculty/staff. According to a food waste audit performed by students on October 22, 2014, total preconsumer waste was 245 pounds. Total post-consumer waste for that day was 229.3 pounds. Of the 245 pounds of pre-consumer produced waste, breakfast represented

45 pounds (18 percent), lunch represented 75 pounds (31 percent), and dinner constituted to 125 pounds (51 percent). Likewise, of the 229.3 pounds of postconsumer produced waste, breakfast represented 44.6 pounds (19 percent), lunch represented 71 pounds (31 percent), and dinner constituted to 113.7 pounds (50 percent). Evidently, food waste production is greatest during dinner and least during breakfast. In total, Colby-Sawyer produces approximately 500 pounds of food waste per day. Per year, Colby-Sawyer produces 54.4 metric tons of organic waste, which results in an annual release of 96.3 metric tons of carbon dioxide.

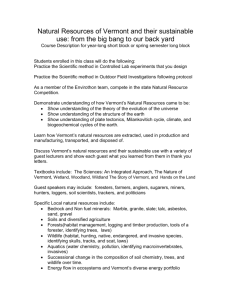

ACUPCC Benchmark Colleges

Green Mountain College

Located in Poultney, Vermont, Green Mountain College is a small liberal arts college with a full-time enrollment of 826. At the heart of Green Mountain’s mission is the Environmental Liberal Arts General Education Program, which combines the skills and content of a strong liberal arts course of study with a focus on the environment. Since, 2007, the college has been growing in their enrollment as well as their building infrastructure. Green Mountain College is the second higher education institution to achieve climate neutrality in 2011, and first to do so with a holistic approach of renewable energy, energy efficiency and carbon offsets (Green

Mountain College, 2014).

According to the STARS report, Green Mountain College received a GOLD rating, with a score of 76.92. With sustainability oriented curriculum that offers a renewable energy and ecological design degree program, a new sustainable agriculture and food production degree, adventure education, natural resources management, and a sustainable MBA program, Green Mountain College received a near-perfect score of 39.80/40.00 for their curriculum. The college is also recognized on the Green Honor Roll under Princeton Review.

9

Farm and Food

Green Mountain College is a pioneer for a sustainable local food system through its Farm and Food Project which is dedicated to closing the loop of the local food system. Through their Sustainable Purchasing Initiative and other local-food related programs, Green Mountain College is setting a national standard for excellence in sustainable food purchasing, student involvement, and campus dining hall innovation. Chartwells Dining Services, Green Mountain College’s food service company, has agreed to use their campus dining hall as a beta testing site for innovative local food purchasing strategies. The college’s Cerridwen Farm, run by students, has a two-acre market garden, an assortment of gregarious livestock, a unique rotational-grazing program, a greenhouse powered by sun and wind and an extensive composting system in conjunction with their dining services. About 12%, or $60,000, of their annual food budget goes to local foods produced on the college farm and regional farms. As of 2014, 36.9% of their dining hall’s food and beverage expenditures are local and community-based (Green Mountain College, 2014).

Recycling and Composting

Since November 2011, Green Mountain College has partnered with Casella

Waste Management to offer Zero-Sort Recycling to their campus. As for organic waste, the college has a student run on-site composting facility. Student volunteers pick up food waste from the kitchen, dining hall and residence hall. The preconsumer waste is fed to the pigs, and the post-consumer waste from the dining hall and residence hall is brought to the farm and kept in a compost pile until decomposition occurs enough for the organic waste to be used as fertilizer on the farm. All college leaves are used in either the composting process or as mulch on the vegetable fields. Worms perform a large portion of the composting process and are plentiful in the compost piles

Middlebury College

Middlebury College is a private liberal arts college located in Middlebury,

Vermont. With a full time enrollment of 2,516 undergraduate students According to

STARS report, Middlebury has received a GOLD rating with a total score of

72.41/100. The college hosts one of the oldest and strong environmental science program run by its Franklin environmental Centre, newly constructed LEED platinum certified building. It has received 27.88/40 for their Curriculum that offers as much as 102 undergraduate sustainability courses and a graduate program.

Additionally, the college offers joint majors also available in architecture and the environment, conservation biology, environmental chemistry, environmental geology, geography, or human ecology. Middlebury offers a wide range of student

10

engagement activities that promotes the idea of living sustainably. The college hosts twenty campus sustainability coordinators that work to promote a culture of sustainable living throughout the campus. The college offers classes like Food geographies, the political Ecology of GMO’s, Economics of Agricultural Transition and food justice. (Middlebury College, 2014)

Farm and Food

Through its Global food program, the college offers a comprehensive food and composting program. The college run dining service spends 32% of its annual budget to purchase local foods. Local foods are defined to be within 250 miles radius of the college. Similar to Colby-Sawyer College, Middlebury uses wholesale distributors like Black river Produce and Burlington Food service as a primary local food supplier. The college dining also receives food from a student run organic farm that was started in 2003. The farm also offers summer internships to four students annually and the stipend for the employees are raised by crop sales. The dining composts nearly 300 tons of food waste annually most of which comes from the colleges’ pre consumer waste. The compost is used by the Facilities management of the school for greenhouses, gardens and soil amendment. (Middlebury College,

2014)

Energy Consumption

The college made significant GHG reductions per student primarily because of the installation of bio mass gasification plant in 2013. The college made significant reductions in its Heating, Cooling and cooking section from 2012-2013 as they launched a $ 12 million bio-mass gasification plant of 8000 Sq. ft. Initial findings reveals that the project is a huge boost towards achieving carbon neutrality by

2016. With a payback period of 12 years, the plant is expected to be a safe investment for the next 30 years. After its full operation in 2013, it avoided use of

1.3 million gallons of fuel annually and reduced net carbon footprints by 66%.

Furthermore, the college poured back 300,000 to the local economy by purchasing more than 18,000 tons of wood chips. (Middlebury College, 2013)

In addition to the biomass plant, the college runs a 147 KW Solar Farm that produced a total of 223,379 kWh of electricity in 2013. In addition, they also run a

10 KW Wind energy plant that helps to generate 15% energy for recycling goods on campus. (Middlebury College, 2014)

University of Vermont

University of Vermont, also known as the University of Vermont and State

Agricultural College is a public research university located in Burlington, Vermont.

11

With a full time enrollment of 9,958 undergraduates and 1,371 graduate students,

University of Vermont is the largest college among our ACUPCC Benchmark Colleges

(University of Vermont, 2014).

According to STARS, University of Vermont has received a GOLD rating with a total score of 65.35/100. Although their Environmental Program is 40 years old, they have received a rather poo rating of 21.79/50 for their curriculum. UVM offers interdisciplinary and individually designed concentrations, including a track in sustainability studies. The Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural

Resources offers majors in forestry, wildlife and fisheries biology, and natural resources. However, their co-curricular score is very strong with a score of

17.74/18 as sustainability is of great importance to the student body, faculty and staff. Their co-curricular education involves Student Sustainability Outreach

Campaign, Sustainability Outreach and Education, etc. Since 2013, the university has established a revolving fund which generates $225,000 each year to finance oncampus energy efficiency improvements. Student activism has ended sales of bottled water in 2013 and brought 100% recycled paper towels and toilet paper to campus (University of Vermont, 2014). UVM was also recognized in the Green

Honor Roll by Princeton Review.

Food and Waste

Similar to Colby-Sawyer College, University of Vermont also has contracts with Sodexo Dining Services for food services, and Casella Waste Management for waste and recycling. UVM Dining is a committed partner in the development of a strong Vermont food system. UVM is the fifth school in the nation, and the first large university east of California, commit to the Real Food Challenge, pledging to serve

20 percent “real food” at all its campus food outlets by 2020. Real food is defined as that which is locally grown, fair trade, of low environmental impact and/or humanely produced. Overall UVM dining serves serve approximately 12% real food.

At Brennan’s, one of their dining location with the mantra “local - organic - sustainable”, they serve approximately 55% real food. In addition to local food in the dining hall, UVM Sodexo has partnered with the Intervale Food Hub to offer local food subscriptions combined with points which allows students to customize food subscriptions and purchase points to use on campus to meet their personal needs

(Sodexo, 2014).

Casella Waste Management offers Zero-Sort recycling at UVM. In 2013, UVM diverted over 43% of its solid waste (by weight) through its recycling, composting and waste prevention efforts. In an average week, UVM diverts over 9 tons (18,000 lbs) of pre-consumer and post-consumer food waste for composting (University of

Vermont, 2014). The food waste from dining halls is picked up by, Casella, which is

12

then transferred to a commercial composting system at Green Mountain Compost , a facility located in nearby Williston, VT, which is owned and operated by the

Chittenden Solid Waste District (CSWD).

Colby-Sawyer College vs. ACUPCC Benchmark Colleges

(i)Gross Emission Ratio Comparisions (ii)Net Emission Ratio Comparisions

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Colby-Sawyer College

Middlebury College

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

-2

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

-4

University of Vermont

Green Mountain College

Figure 8: Colby-Sawyer College's Emission Ratios compared to ACUPCC Benchmark

Colleges

Among all the four colleges, Colby-Sawyer College ranks second in terms of gross as well as net emission ratio per student, with Green Mountain being the first as it achieved carbon neutrality in 2011. Colby-Sawyer College significantly reduced their net emission in 2011 by having 100% renewable electricity through the purchase of Renewable Energy Certificates. However, there are still opportunities for Colby-Sawyer to learn from these ACUPCC Benchmark Colleges.

Green Mountain College: Climate-Neutral Campus

Green Mountain College signed the American College and University

President's Climate Commitment in 2007, with a goal of becoming a carbon-neutral campus by 2014. In 2011, Green Mountain College became the second higher education institution in the country to achieve climate neutrality, and first to do so through a holistic approach of energy efficiency, renewable energy and carbon

13

offsets. The College reduced its emissions by 30% before 2011 through efficiency projects and replacement of its central heat plant with sustainability-sourced biomass in April 2010. After these reductions, GMC became climate neutral in 2011 by purchasing verified carbon offsets from a local farm methane project that were registered and retired on the Chicago Climate Exchange (Green Mountain College,

2014). The College has maintained neutrality since 2011 and continues to find innovative ways to reduce their gross emissions.

Middlebury College: Path to Climate Neutrality

In 2007, Middlebury College signed the American College & University

Presidents' Climate Commitment to achieve carbon neutrality by 2016. Over the past year seven years, the school had a slight decrease in the number of full time students while total building size remained the same. Even though the college has a total gross emissions of 12729 metric tons of CO2 in May,2014 , their net emissions had decreased significantly as the college purchases carbon offsets from Native

Energy (Vermont) equal to the estimated amount of emissions from the college owned Snow Bowl ski are. Net emission per student is only .8 which is one of the best among private institutions. The reduction in net emissions mostly comes from the establishment of Biomass gasification plant in 2013.

University of Vermont: Path to Carbon Neutrality

In 2007, University of Vermont signed the American College & University

Presidents' Climate Commitment, and created the Office of Sustainability shortly afterwards. In December 2010 UVM committed to climate neutrality by 2025. Over the past 7 years, enrollment at UVM has significantly increased from 10341 to

12,247 student (University of Vermont, 2014). The increased enrollment and new technologically complex buildings has increased energy demands for the campus, while LEED policy, upgrades to central heating/cooling plant, and associated infrastructure has resulted in reducing the emissions. UVM is currently in negotiation with their municipal electric utility to address their first target of carbon neutral electricity by 2015 through the purchase of Renewable Energy Certificates.

Overall, one lesson to learn from these three benchmark college is that Colby-

Sawyer College could significantly reduce their gross as well as net emission by investing in a bio-mass plant for heating. This would offset all the emissions that the college currently produces by using propane for heating the infrastructures.

14

Other Benchmark Colleges

Bowdoin College

Bowdoin College is a highly selective, private liberal arts college located at

Brunswick, Maine. With an overall full time enrollment of 1803 students, the college is heavily invested into green practices. In 2007, the college committed to achieve carbon neutrality by 2020 with the goal of reducing gross emission by at least 28% by 2020. Bowdoin’s comprehensive sustainability practices especially in Food and waste make them one of the pioneers of the industry. The college ranks fourth in the

Princeton review’s list of Best College food. It makes a particularly good benchmark for Colby-Sawyer as the college is heavily invested into its local food program, student run organic garden and more importantly, making students aware about the food they are being served. (Bowdoin College, 2014)

Food Input to the school

Bowdoin College offers two dining halls run by the Bowdoin Dining service. 34% of the foods in the dining halls come from local sources. Local foods are defined to be grown and processed within 250 mile radius of the college. The college makes it local food purchase from Fresh Farm connection, a program of Maine Sustainable society that was started in 2002 which works to establish connection between the college and local farmers. The farm encourages organizations to promote organic and local foods with the motto of achieving a “culture that supports food, family and farms”. Some of its other vendors include Quahog Lobster, Oakhurst Dairy,

Greenwood Orchards and Swan's Honey. (Bowdoin College, 2014)

Student Run organic Garden

Since 2004, the college operates certified student run organic farms that produce fruits and vegetables. The farm employee student workers throughout the year and also offers additional research opportunities related to agriculture and food for students and faculty members. They manage two farms that grow seasonal crops which accounts to 16.4% of the foods served in the two dining halls. The garden is supported and maintained by the Bowdoin organic garden club that recruits volunteers to help garden crops as well as assist in fundraising events. The club primarily raises money by organizing farmers market on campus, t-shirt sales and crowdfunding. Furthermore, the garden donates 10% percent of its produce to the

Mid Coast Hunger Prevention program.

Other Initiatives

15

Any surplus food from the dining hall is donated to Mid Coast Hunger Prevention

Program (MCHPP), a local food pantry and a soup kitchen. In addition, they donate more than 900 lbs. of fresh organic foods from the college farm to the program. It also hosts a monthly donation to Tedford Family shelter that caters more than 25 families. (Sustanabiity Office, p. 70)

The college is also taking significant measures to reduce the purchase of bottled water by providing ceramic water containers during college meetings and catering events. Bowdoin Student Government has an annual program that offers students

50% off the purchase of reusable water bottles at the college bookstore.

(Sustanabiity Office, p. 72)

Lafayette College

Lafayette College is a private liberal arts and engineering college located in

Easton, Pennsylvania, with a full-time student enrollment of

2,488. Lafayette College has taken initiative by diverting food waste using on-site composting units. In May of

2010, Lafayette installed two

Earth Tubs in hopes of composting all of the postconsumer waste on campus

(AASHE, 2011). Earth Tubs are sold by Green Mountain

Technologies and are specifically designed for the onsite composting of food waste.

Figure 9: Mechanisms of an Earth-Tub

Essentially, an Earth Tub is a fully enclosed composting vessel that features power mixing, compost aeration, and biofiltration of all process air. The Earth Tub can process a minimum of 50 pounds of pre/post-consumer waste, and a maximum of

150 pounds per day (Green Mountain Technologies). It takes 3.5 weeks for an Earth

Tub to fill at a rate of 150 pounds per day (Green Mountain Technologies).

Furthermore, it takes an additional 2 weeks for food waste to bake and convert into compost (at this point time, no supplemental food waste can be added to the tub)

(Green Mountain Technologies). Of the total food waste put into the system – a tub has a holding capacity of approximately 3,200 pounds – the Earth Tub is able to generate 45 percent compost (Green Mountain Technologies). In other words, if a tub holds 3,200 pounds of food waste, it will generate 1,440 pounds of compost. The

16

Earth Tub performs exceptionally well in cold weather conditions, as it is well insulated, and will retain internal heat even if temperatures remain at ten degrees

Fahrenheit for seven days (Green Mountain Technologies). Additionally, the biofiltration air purification system will remove all odors stemming from the composting process. The overall cleanliness of the system allows for the Earth Tub to be placed in public locations.

Lafayette College was able to purchase two Earth Tubs and two small-scale pulpers with a $40,000 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection grant (AASHE, 2011). As of July 2010 (14 months after the initial purchase),

Lafayette was able to compost over 14,000 pounds of food waste (AASHE, 2011).

The college uses that compost to offset organic fertilizer used for landscaping purposes. Lafayette has two students complete all required manual operations (the tub requires twenty minutes of daily maintenance) (AASHE, 2011). A complete user guide to the tub is provided through the Green Mountain Technologies’ website.

Rutgers University

Rutgers University, the state university of New Jersey, is located in New

Brunswick, NJ. It is the largest university in the state, with a full-time student enrollment of 65, 512. Rutgers is home to the third largest student dining operation in the country, serving over 3.3 million meals and catering to over 5,000 events each year (EPA, 2009). The student dining halls produce approximately 12,500 pounds of food waste per day (EPA, 2009). However, Rutgers purchased a large-scale food pulper to pulverize food waste in order to drastically reduce the volume of food waste. The pulper, which was originally purchased for $45,000, pulverizes food scraps and removes excess water (EPA, 2009). This pulper is able to reduce food waste volume by as much as eighty percent. Essentially, the pulper can reduce

12,500 pounds of food waste to a mere 2,500 pounds, or 1.125 metric tons (EPA,

2009).

Instead of sending pulverized food waste to the landfill, Rutgers elected to divert food waste to a local pig farm, Pinter Farms. Pinter Farms, which is located less than fifteen miles away, collects all 1.125 metric tons of pulverized food waste on a daily basis. This food waste is then used to feed the farm’s hogs and cattle. For

Pinter’s services, the farm charges Rutgers half the cost it would take the university to otherwise haul the food waste to a landfill. There is an enormous economic benefit associated with Rutgers’ food scraps diversion system. In 2007, Rutgers’ partnership with Pinter Farms saved Dining Services more than $100,000 in avoided hauling costs (EPA, 2009). The food pulper, which was purchased for

17

$45,000, and has a yearly maintenance cost of $500, was paid for within half a year of diversion.

In addition to the economic incentive associated with the diversion of food waste to pig farmers (if food waste hauling costs apply), there are two considerable environmental benefits. As mentioned previously, feeding food scraps to animals avoids landfill methane generation. Secondly, food waste is an effective way to provide animals with feed. Food waste that functions as animal feed can preserve large quantities of valuable resources, such as fresh water and arable land, since less feed (e.g. grain) needs to be agriculturally produced. Rutgers serves as a benchmark, because it demonstrates that diversion of food waste to pig farmers can be accomplished at a university of virtually any size. One of our recommendations focuses on establishing new partnerships with pig farmers to divert pre-consumer waste only.

Recommendations

Increasing Local Foods

Since the local food initiative started, Sodexo Dining Services at Colby-Sawyer

College has committed to providing more local food offerings in the dining hall. Over the course of 2 years, we have been able to provide at an average of 28% local food.

However, there are still more opportunities for the college to expand on their local food offerings. Some of the recommendations that we have identified that would help the college increase the percentage of local food offered are as follows:

Transitioning to “Hyper-Local” Foods

When the initial Local Food petition was drafted in 2011, the student group stated the 100 mile radius based on the calorie intake for the college and availability of farms that could potentially supply to the college. They calculated this food demand for the college using the following equation:

Amount of Food bought-Food Wasted= Total calorie Intake for the College

Our group initially looked into expanding our local food radius to 250 miles, as described by Real Food Challenge that many colleges with Sodexo Dining Services such as University of Vermont have applied to in the definition of “local.” However, given our college’s small population and abundance of many local farms in the region, we decided to maintain the “100 mile radius” as the definition of “local” for

Colby-Sawyer College.

18

Instead of expanding the radius, we now would like to recommend the college to source food from “hyper-local” farms -- farms that are located within the proximity of 45 minute driving distance from the college.

Transitioning to hyper-local farms means buying produce, meat, dairy and other products from the farms that are at the closest proximity from the college first, then looking into farms that are farther away. The benefits of dealing with “hyper-local” farms is that it benefits the local economy around New London, as well as

Figure 10: 100 mile radius with a "hyper-local' radius from Colby-Sawyer College strengthens the community relationships with the various farms and community members. Sourcing food from hyper-local farms would also decrease the carbon footprint of the food, and they will be travelling less miles to get on our plates. Although, there might not be as much economic benefits of transitioning into “hyper-local” food, the environmental and health benefits are much greater. With food that travels less than 45 miles, students will be able to eat fresh, organic and local food from farms where they can visit to see how their food is being produced.

19

Figure 11 shows the New

London food shed as described by our hyper-local definition.

According to the

Kearsarge Regional

Food System Analysis done my Communitybased Research

Project 2012, there are over 57 farms of various capacity within this food-shed.

Within this food-shed, we have identified 22 farms that potentially have the capacity to supply local food to

Colby-Sawyer College

(See Appendix A).

Some of these farms already relationship have with

Black River Produce which would make it easier for Sodexo to purchase from them.

Figure 11: New London “Hyper-Local” Food-Shed as described by a

45 minute driving radius from Colby-Sawyer College

20

Reducing Food Waste

One of the major obstacles for buying local food is the expensive cost of buying local. There are no extra funds being generated while the demand or local food increases. So, one the ways of offsetting this cost is to reduce food waste so that the savings can be used to purchase more local food.

In an average day Colby-Sawyer Dining generates about 500lbs of organic waste, much of which could be easily reduced such as the pre-consumer waste – the food that was prepared but not eaten – as well post-consumer waste— the leftover food thrown out by students. By reducing this waste, we can help reduce the cost of the food that is currently being bought and thrown out by the students. We can use that savings to help fund the local food initiative that the students have petitioned for.

Some of the ways we could reduce food waste are as follows.

The Clean Plate Club Initiative could be implemented more often to educate the students about food waste. Previous initiatives has seen a reduction of

26% food waste over a span of 2 weeks.

“Please eat and drink whatever you take from the serving lines” should be a consistent message during meals.

Everyone should be encouraged to take less the first time around so that they know that they could always come back for a freshly cooked second portion if they were still hungry after eating the first.

Continue Collaboration for Easier Access to Local Food

Since Sodexo is a global corporation, there are many corporate laws and regulations that Sodexo has to adhere to while conducting the dining services at the college. While the college demands for more local foods, there are several challenges and barriers that create obstacle for local farms in the region to supply to the college. We have identified some of these challenges and solutions to those challenges, which in the future could potentially help us gain access to more local food.

Challenges:

1) Liability issues and Inspection Process: Sodexo has a $5 million requirement for liability and many small farmers may not be able to afford this level of coverage. Additionally, vendors that partner with Sodexo must be certified purveyors and go through a time-consuming documentation process annually, which includes GAP Standards and more. This costs between $1500-

1800/year.

21

2) Distribution: There is convenience inherent in Sodexo’s current ability to quickly and reliably order large volumes of food from one distribution center, currently Black River Produce. Picking up products from several smaller farmers or distribution centers might add time, and miles/carbon, to that process.

3) Cost: Many local products cost more at face value and Sodexo may lose its advantage of keeping costs low by buying in large volumes if we use many smaller vendors.

Solutions:

1) Liability issues: Investigate alternative models/mechanisms for using smaller farmers who cannot afford to carry this sort of coverage. Sodexo should continue to work with small farmers to help them through the inspection process, as some farmers will see this cost and effort as a longterm investment, especially when Sodexo can provide guaranteed increase in purchase volume. Some alternative models could include: a.

Working with particular farms growing particular products selling to institutions through distributors. b.

Colby-Sawyer buys the food themselves taking onto the safety issues, similar model to Bowdoin College and Green Mountain College.

In September 2014, Sodexo in Vermont Colleges announced their

‘Vermont First” strategy stating their commitment to investing in the production and procurement of local food in their Vermont food service contracts. Under the “Vermont First” program, Sodexo will work with farmers, distributors, processors, state government, non-profits and supply chain players within the farm to institution sector to increase the amount of local food grown and sold in the state and beyond (See Appendix B). Michael

Ward, Sodexo’s District Manager is working with the stakeholders for a similar strategy in New Hampshire. Such framework for local food could make the college’s access to local food much easier.

2) Distribution: There is currently talk within NH about developing a local food hub in Boscawen, NH. Such food-hubs could potentially be another distributor in addition to Black River Produce.

3) Cost: Work with students to educate them about the value and challenges of buying more local food and get them involved in decisions that might involve choosing between some foods over others in order to keep budget stable.

Another one way to free up additional money for local food is to address the issue of food waste.

22

Reduce the Use of Bottled Water

With highly selective private liberal arts colleges like Bowdoin, Middlebury,

Oberlin and Macalester moving towards banning the sales of plastic water bottles inside the college, our group believes that it is the next major environmental initiative that can be initiated by Colby-sawyer College. Reducing the use of plastic water bottles would further exemplify President Galligan’s commitment in 2007 in reducing our carbon footprints by 25% by 2015 and achieve carbon neutral by

2050.

“Plastic bottle production in the United States annually requires about 17.6 million barrels of oil, enough to fuel at least one million cars.” (Sustainable Table, 2014) The environmental impacts on plastic bottles are huge and we strongly recommend the school to encourage and aware students about this. The advantages of using tap water over bottled water are numerous: it is cheap, reliable and eco-friendly. While a Bottled water typically costs more than $1 for eight to 12 ounces i.e. more than

$10 per gallon while tap water typically costs $0.002 per gallon. (Sustainable Table,

2014)

While the college is making commendable efforts towards increased accessibility to drinking water, we are still far from completely eliminating the plastic water bottles on campus. From our findings, we believe that eliminating the use of plastic water bottles is a very achievable goal if we adopt persistent strategies to aware the school community about the environmental benefits of using reusable water bottles over single use plastic bottles. Our group recommends three stages of implementation:

Launching the take back the tap initiative to create awareness, Selling and distributing reusable water mugs and Retrofitting water fountains and removing plastic bottle availability from vending machines.

Take Back the Tap Initiative

Started in 2005, Take Back the tap is a nationwide campaign of Food & Water

Watch, a non-profit organization that works to reduce and raise awareness about the negative impacts of using plastic water bottles. The organization works closely with a campus coordinator who will be responsible in organizing events and discussions aimed at discouraging the use of plastic water bottles. This will include organizing hall program by collaborating with Resident Assistant (RA) and movie screening programs collaborating with Office of Sustainability and Eco-Rep’s. The student will also be compensated with $500 at the completion of the project. The student will be responsible to put flyers that promote a habit of using hydration stations around the campus. (Food & Water watch, 2014)

23

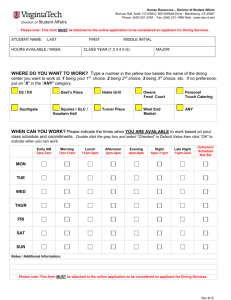

Free distribution of Reusable water mugs

Our group decided that providing free reusable water bottles and a campus wide map locating water fountains and bottle fillers for the freshmen group will be a viable option for the college. The goal is to instill in them positive attitude towards reducing the use of plastic bottles. Also, first year students are more susceptible to changes and it is likely that they will positively embrace the idea and help promote

Colby-Sawyer’s sustainability initiatives. A college wide survey can be taken before deciding on the size and design of the mug.

As mentioned in the school report plan by Green Routes, producing 1000 reusable mugs will cost about $2000(adjusted with inflation rate). When sold at a selling price of $5 at the bookstore, we only need to sell the first 500 units to get our breakeven. The rest 500 mugs can be used to make free distributions at the orientation following a small talk session.

Retrofitting Water-Filling Stations

In order to make an easy and safe access to drinking water, we came to a conclusion that retrofitting water fountains serves to be the cheapest and most sustainable model. The college currently has 20 water fountains and 3 bottle fillers in eight administrative buildings. (Refer to Appendix) The current infrastructure is nowhere enough to meet the student size of the campus. Based on research from other benchmark schools, we recommend installing 20 filling stations in 11 residence halls and 5 in the eight administrative buildings. University of Vermont currently has 215 water fountains and 75 bottle fillers in a campus with a size of

9,958 undergraduates and 1,371 graduate students. (Office of Sustanability, 2012)

Our group identified possible locations to install hydration station in two out of the eight administrative buildings. We thought that it made more sense to immediately install 2 fountains in higher traffic buildings--Colgate and Library. We recommend the college to use similar model to the one that we have in Colgate and Dining Hall i.e. EZH2O® Bottle Filling Station with Single ADA Cooler at Colgate and Dining

Hall.(See appendix for product specifications) We recommend using similar model at new stations. The model costs around $1200 and is one of the cheapest available in the market. Furthermore, we also recommend relocating some of the fountains in

Ware campus to a more visible location where water consumption is higher than in other locations. We also found out that retrofitting old water fountains with additional feature would be the best solution for the old fountains located at

Reichold and Library.

In addition, we decided that it was reasonable for the college to install at least one hydration station at each of the residence hall. Currently, no residence halls inside

24

the campus has a hydration station and only suite style dorms i.e. Lawson and

Danforth offers a comparatively easy access to tap water. Bigger residence halls like

Burpee and Best would require multiple hydration stations to cater the demand. It is especially recommended to install new stations at the newly announced Freshmen

Dorms (Lawson, Colby and Best) so that to encourage the use of the reusable mug provided during the orientation.

The college has contracted Elkay to retrofit most of its existing water fountains. We recommend the college to use Filtered EZH2O® Bottle Filling Station with Single

ADA Cooler like Colgate and Dining Hall. According to the sales details provided by

Davenport Associates (NH Sales representative for Elkay), the cost of installing 20 new fountains in residence halls comes to be approximately $26,000. (Refer to appendix for product specifications)

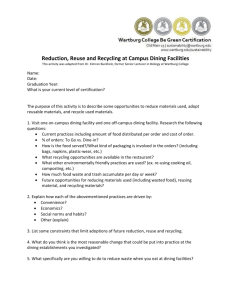

Organic Waste Diversion

Colby-Sawyer College must take initiative in exploring sustainable alternatives to organic food waste disposal. This report offers separate recommendations for the diversion of pre-consumer and post-consumer food waste.

Pre-Consumer: Partnership with Local Pig Farms

Our group’s first recommendation for diverting dining hall food waste is to establish partnerships with local pig farmers. Our group has determined that it is most viable to only divert pre-consumer waste to pig farmers. The diversion of postconsumer waste to pig farmers is not a feasible proposition. This is mainly due to two reasons: contamination and regulation. Post-consumer waste was an issue of contamination in past college partnerships with pig farmers. Unlike post-consumer waste, the college can ensure that pre-consumer waste will not be contaminated with utensils (e.g. forks, knives, etc.). Pre-consumer waste does not reach the plates of students/faculty/staff. Therefore, there is a minimal risk of accidental utensil contamination when food waste is disposed of.

In addition to contamination, post-consumer waste that is provided to pig farmers is subject to extensive federal regulation. Under the Federal Swine Health Protection

Act, all foods that contain, or have come into contact with meat or animal products must be regulated (Federal Register, 2009). This measure applies directly to postconsumer waste, since there is no way to distinguish whether or not post-consumer waste has come into contact with meat. In Colby-Sawyer’s case, there is a strong likelihood that food on student’s plates will have come into some form of contact with meat even before it arrives to the food sorting bucket system. The Swine Health

Protection Act requires that all post-consumer food must be boiled to a minimum of

212 degrees Fahrenheit, for a duration of thirty minutes before being fed to pigs

25

(Federal Register, 2009). Additionally, facilities conducting heating will need to be certified with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to do so. Essentially, federal regulation makes it difficult for pig farmers to offer post-consumer waste as feed to their pigs. Consequently, our group believes that it most practical to divert preconsumer waste to pig farmers.

The notion of diverting pre-consumer to local pig farmers is an appealing prospect to many farmers. For example, our group has coordinated closely with the

Vegetable Ranch, an organic farm located in Warner, NH. The farm is run by longtime USDA Certified Organic farmer, Larry Pletcher. According to Mr. Pletcher, a pigs’ diet is extremely flexible, and can accommodate any type of pre-consumer food waste (fruits, veggies, doughnuts, cake are all acceptable items). In addition to growing organic produce, the Vegetable Ranch currently owns seventeen adult pigs, each of which can consume five pounds of pre-consumer waste on a daily basis.

Essentially, the Vegetable Ranch could support eighty-five pounds of daily preconsumer waste. Since the college produces approximately 250 pounds of preconsumer per day, Mr. Pletcher’s farm could offset thirty-five percent of Colby-

Sawyer’s pre-consumer waste alone.

In addition to diverting food scraps to the Vegetable Ranch, Colby-Sawyer could establish relations with other local pig farms to divert the remaining 165 pounds of pre-consumer waste. Suggestions include Sugar River Farm in Newport,

NH, and Cascade Brook Farm in North Sutton, NH. Our group specifically recommends these farms because they are closest to the college, thereby minimizing transportation costs and the transportation carbon footprint.

From an economic standpoint, Colby-Sawyer could arrange a zero-cost exchange with participating pig farmers. Colby-Sawyer would provide participating farms a favor by supplying pig feed that farmers would otherwise need to produce or purchase using their own land/funds. Farms would provide Colby-Sawyer a favor by providing their own transportation to haul and divert food waste. Ideally, these favors will offset one another and result in a zero-cost exchange. Additionally,

Colby-Sawyer could also arrange to purchase products (such as veggies or eggs) from participating pig farms. Such an arrangement can assist the college in its transition towards a more hyper-local foods system (another recommendation of ours). Ultimately, the college can proceed to communicate with local pig farmers in terms of establishing some form of contract. It is important to determine how much pre-consumer food waste must be apportioned for each participating farm.

Furthermore, it is important to arrange a fixed system/schedule in which farmers travel to collect waste from the college.

26

Post-Consumer: Earth Tub Systems

While our first recommendation focuses on diverting pre-consumer waste to local pig farmers, it does not discuss the diversion of post-consumer waste. Using

Lafayette College as a benchmark, our group strongly believes that the purchase of

Earth Tub Systems provides the college with effective solution for the diversion of post-consumer waste.

As mentioned previously, Colby-Sawyer produced 230 pounds of postconsumer waste on October 22 nd . On average, the college produces close to 300 pounds of post-consumer waste every day. An Earth Tub can process a minimum of

50 pounds of post-consumer food waste per day, and a maximum of 150 pounds. It would make most sense to follow the two-tub model, in which two Earth Tubs are used in combination. If one follows the two-tub model, then the college will be able to fill a single tub for a period of 3.5 weeks. Again, it takes 3.5 weeks for an Earth

Tub to be filled at the maximum rate of 150 pounds per day. Since it takes two additional weeks for an Earth Tub to bake, no food can be added to the system during that time frame. Hence, it makes sense to follow the two-tub model. As soon as baking begins in the Tub 1, post-consumer waste can continue to be added to Tub

2 (for purposes of explanation, our group will refer to the tubs as Tub 1 and Tub 2.).

Once baking concludes in Tub 1, one can remove all compost and restart the process of filling the tub. At this point in time, both tubs can be filled with food waste simultaneously. While Tub 1 is in its baking stage, Tub 2 is in use for the first 2 weeks out of the 3.5 weeks. Essentially, after Tub 1 has completed its two week baking process (and is ready to be filled again), both tubs can be filled with postconsumer waste for the remaining 1.5/3.5 weeks. This cycle of 3.5 weeks can occur at least eight times over the course of a 30 week school-year. For purposes of calculation, Colby-Sawyer can achieve 8 cycles for a total of 28 weeks.

If one tub can be filled for two weeks at a rate of 150 pounds, it will generate

2,100 pounds of food waste. Additionally, two tubs will be able process 300 pounds of food waste a day for 1.5 weeks, totaling 3,150 pounds. This results in a grand processing total of 5,250 pounds of diverted post-consumer waste every 3.5 weeks.

If this 3.5 week standard can be achieved for a total of 8 cycles, then the Earth Tubs are able to collect 42,000 pounds of food waste per 28 weeks (5,280 pounds x 8 cycles = 42,000 total pounds). Green Mountain Technologies states that an Earth

Tub is able to produce a 45% food waste to compost reduction ratio. Hence, both

Earth Tubs will be able to generate a grand total of 18,900 pounds of compost for 28 weeks (42,000 total pounds x 45% = 18,900 pounds).

From an economic standpoint, Green Mountain Technologies sells two Earth

Tubs for a total of 17,895 dollars (Green Mountain Technologies). The two Earth

27

Tubs will use a combined total of 4-6 kWh to power the auger (Green Mountain

Technologies). This results in an annual electric cost of approximately 200-300 dollars (Green Mountain Technologies). Additionally, the Earth Tub needs requires twenty minutes of daily maintenance. The auger needs to be turned on each day, and manual labor is required to perform two revolutions of the tub’s rotating cover in order to mix the outside and center of the Earth Tub. Daily maintenance does not have to result in a cost, since volunteer students can perform those necessary functions. Additionally, the loading of food waste into the Earth Tub systems can be performed by Sodexo staff or students. There is no additional cost associated with this process since Sodexo staff is already tasked with the storage of food waste for

Casella pick-up. Staff or students must only be re-trained to properly store and load the Earth Tubs.

According to the Landscaping & Biodiversity group, Colby-Sawyer purchases

21,460 pounds of organic fertilizer annually. This fertilizer costs $1.39 per pound. If the Earth Tubs can offset 18,900 pounds of organic fertilizer, then the college can save $26,271 of purchased organic fertilizer each year (18,900 pounds x

$1.39/pound = $26,271 saved dollars). If any Earth Tub produced compost is not needed to offset organic fertilizer (for example, it would not be practical to apply compost to athletic fields), then the college can elect to sell excess compost.

However, it is not possible to create a calculation to see how much compost can be sold for, given the fact that it would depend on the nature of the contract between the college and purchaser. It is important to realize that if all compost can offset organic fertilizer, then the purchase of the Earth Tubs pays for itself within a year.

Additionally, Colby-Sawyer can explore potential grant opportunities to cover the cost of the purchase. The estimated life span of an Earth Tub is 15 years (Green

Mountain Technologies).

Conclusion

Overall, Colby-Sawyer College has been progressing towards a more sustainable culture in terms of food and waste. However, there are opportunities for the college to improve on some aspects. Since the local food initiative, Sodexo Dining Services have worked diligently with Black River Produce to source more local food and remain within the budget. We hope that they continue to work on source more local food increasing our total percentage of local food served, and eventually transition

28

into “hyper-local” foods. Local food costs significantly more than food that have been produced in corporate farms. So, in order to generate cost saving in order to purchase more savings, we could look into reducing the food waste from the dining hall.

In terms of waste and recycling, the college’s diversion rate has increased to 31%.

However, with the increase in the total waste generated, there are many opportunities for us to improve our recycling practices. We recommend the college to adopt persistent strategies to aware the school community about the environmental benefits of using reusable water bottles over single use plastic bottles.

Colby-Sawyer College’s biggest drawback currently is the disposal of organic waste into the landfill. Sending the organic waste into the landfill not only generates more potent gases, but also the mineral rich organics are losing their value. Organic waste could be composted to produce compost as well as feed for pigs. Therefore, we strongly recommend the college to divert pre-consumer food waste to local pig farmers, and invest in a two Earth-Tub System to process the post-consumer food waste. Investing in the Earth-Tub System is not only environmentally sustainable but also economically feasible, as the system would produce enough organic compost for the college’s use offsetting the cost of purchasing compost from elsewhere.

29

References

AASHE. (2011, May 11). Earth Tub Composting. Retrieved from The Association for the Advancement of

Sustainability in Higher Education: http://www.aashe.org/forums/earth-tub-composting

Bowdoin College. (2014). Carbon Neutrality. Retrieved from Sustainability: http://www.bowdoin.edu/sustainability/carbon-neutrality/index.shtml

Bowdoin College. (2014). Dining services. Retrieved from Bowdoin college sustainability: http://www.bowdoin.edu/sustainability/dining/index.shtml

EPA. (2009, October). Feeding Animals: The Business Solution to Food Scraps. Retrieved from U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency: http://www.epa.gov/wastes/conserve/foodwaste/success/rutgers.pdf

Federal Register. (2009, December 9). Swine Health Protection; Feeding of Processed Product to Swine.

Retrieved from Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States Government: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2009/12/09/E9-29265/swine-health-protectionfeeding-of-processed-product-to-swine

Food & Water watch. (2014). Take back the tap. Retrieved from http://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/water/take-back-the-tap/students/

Green Mountain College. (2014). GMC's Farm & Food Project. Retrieved from Green Mountain College

Website: http://www.greenmtn.edu/farm_food.aspx

Green Mountain College. (2014). Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory. Retrieved Decemer 2, 2014, from http://sustainability.greenmtn.edu/operations/ghg_inventory.aspx

Green Mountain Technologies. (n.d.). Earth Tub. Retrieved from Green Mountain Technologies:

Commercial Composting Solutions: http://compostingtechnology.com/products/compostsystems/earth-tub/

Middlebury College. (2013). FAQ's. Retrieved from Middlebury College Bio Gasification: http://www.middlebury.edu/sustainability/carbon-neutrality/biomass/faq

Middlebury College. (2014). Global food program. Retrieved from Middlebury College Sustainable food: http://www.middlebury.edu/sustainability/food

Middlebury College. (2014). What's Middlebury's path towards neutrality? Retrieved from Middlebury

College sustainability: http://www.middlebury.edu/sustainability/carbon-neutrality/projectsprogress

Office of Sustanability. (2012). The Bottle Water Campaign at UVM:. Retrieved from UVM: http://www.uvm.edu/~uvmppd/allhands_ppts/2012ah-bottledwater-thompson.pdf

Sodexo. (2014). Campus Initiatives. Retrieved from UVM Dining Services: https://uvmdining.sodexomyway.com/community/local.html

Sustainable Table. (2014). Water. Retrieved from Sustainabletable.org: http://www.gracelinks.org/media/pdf/bottled_water_tp_20090703.pdf

30

Sustanabiity Office. (2014, March 11). Sustanability report. Retrieved from STARS: http://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/sierra/coolschools/2014/pdfs/2014-

03-11-bowdoin-college-me.pdf

University of Vermont. (2014, 2014). Sustainability at UVM. Retrieved from UVM Office of Sustainability: http://www.uvm.edu/sustain/sustainability-at-uvm

31

Appendices

Appendix A: Potential Hyper-Local Farms

Farms with Black River Produce Partnership

Farm

Spring Ledge Farm

Greg Berger

37 Main Street

New London, NH 03257

Tel: 603-526-2080 and 603-526-6253

Fax: 603-526-6679 info@springledgefarm.com

http://springledgefarm.com/

Yankee Farmer's Market

Keira & Brian Farmer

360 Route 103 East

Warner, NH 03278

603-456-BUFF (2833) kefarmer@tds.net

yfm@tds.net

Vegetable Ranch

Larry and Carol Fletcher vegetableranch@gmail.com

Kearsarge Mtn. Road

Warner, NH 03278

603-496-6391

Beaver Pond Farm

50 McDonough Road,

Newport, NH 03773

Tel:603-542-7339 or 603-543-1107 http://www.bpondfarm.com/ becky@bpondfarm.com

and bpf@nhvt.net.

Warner River Organics

Jim Ramanek

119 Dustin Road

Webster, NH 03303

Products

Veggies

Corn

Strawberries

Buffalo & Natural

Local Meats

Organic vegetables,

eggs,

Pastured Pork

Assorted veggies

Homemade Pies

Apples

Maple Syrup

Fruit,

Veg,

Grains, plants,

Miles

2

15

17

19

21

32

603-746-3018 warnerriverorganics@tds.net

jim.ramanek@gmail.com

North Country Smokehouse

471 Sullivan St

Claremont, NH 03743

Phone: 603- 543-0234 https://ncsmokehouse.com/

Surowiec Farm

53 Perley Hill Road,

Sanbornton, NH

603-286-4069 www.surowiecfarm.com

Hemingway Farms

1815 Claremont Road

Charlestown,

NH 03603

603-826-3336 http://www.hemingwayfarms.com/Hemingway_Fa rms/Welcome.html

Peachblow Farm

Bob and Polly Frizzel

Old Claremont Road

Charlestown, NH

Phone: 603-826-3980 and 603-826-5729

Cell: 603-398-8090 http://www.peachblowfarm.com/

Frizzells@myfairpoint.net

Mitchell’s Fresh est. 2006

PO Box 74

Concord, NH 03301 http://www.mitchellsfresh.com/ www.facebook.com/MitchellsFresh info@mitchellsfresh.com

Shiitake mushrooms

Assorted meats

Bacon

26

PYO Apples,

Pumpkins,

Vegetables,

Corn,

Tomatoes,

Winter Squash

27

Assorted Veggies 30

Asparagus

Veggies

Salsas,

Dips

33

35

33

Beans and Greens Farm

Andy and Marina Howe

245 Intervale Road

Gilford, NH

603-293-2853

Beansandgreensfarm@msn.com

Beans and greens farm.com

Moulton Farm

18 Quarry Road

Meredith, NH 03253

603-279-3915 moultonfarm@metrocast.net

http://www.moultonfarm.com/

Boggy Meadows Farm

13 Boggy Meadow Lane

Walpole,

NH 03608

Tel: 603-756-3300 https://www.boggymeadowfarm.com/

Alyson Apple Orchard

57 Alyson Lane

Walpole

NH 03608

Tel: 603-756-9800 http://www.alysonsorchard.com/ info@alysonsorchard.com

New Hampshire Mushroom Company

Eric Milligan

153 Gardner Hill Road

PO Box 182

Tamworth, NH 03886 eric@nhmushrooms.com

www.nhmushrooms.com

Echo Farm Puddings

Hinsdale, NH 03451

Phone: 603-336-7706 (866) 488-ECHO http://www.echofarmpuddings.com/

39

Veggies

Bakery

Cheese

41

47

Apples 50

Fresh Grown and

Dried Wild organic

Mushrooms

62

Puddings 69

34

PT Farm LLC

500 Benton Road,

North Haverhill,

NH 03774

Tel: 603-787-9199

FAX (603)787-9198 http://newenglandmeat.com/about/

Beef

Pork

80

35

Other Local Farms Worth Considering.

Farm

Coffin Cellars Winery

Peter, Jamie, or Tim Austin

1224 Battle Street

Webster, NH 03303

603-731-4563 http://coffincellarswinery.wix.com/home-1

Contoocook Creamery

Bohannon Farm, Heather or Jamie

945 Penacook Road

Contoocook, NH 03229

603-717-5863 www.contoocookcreamery.com

Henniker Brewing Company, LLC

Microbrewery – Farmers’ Markets and events

Christopher Shea, Head Brewer

129 Centervale Road

P.O. Box 401

Henniker, NH 03242-0401

603-428-3579

Cell: 617-955-6257

CAhea@HennikerBrewing.com

Brookford Farm

Luke & Catarina Mahoney

250 West Road

Canterbury, NH 03224

Tel: 603-742-4084 www.brookfordfarm.com

Miles Smith Farm

Carole Soule, & Bruce Dawson

56 Whitehouse Road

Loudon, NH 03307

Tel: 603-783-5159

Products

wines from local berries

Miles

21

Milk,

Butter,

Cheese

Beer

Pasture Raised

Meats

Milk, Cheese

Grains - Flour

Farmstead

Creamery

Naturally raised beef

31

49

36

23

23

beef@milessmithfarm.com

www.milessmithfarm.com

Appendix B: Summary of “Vermont First” Strategy

The “Vermont First” strategy includes the following commitments by Sodexo:

Communications

1.

A formal commitment and investment that supports the production and purchase of local food.

2.

The hiring of a local food coordinator by the company to broker relationships with growers wanting to meet the institutional market demand.

3.

Establish a definition for local products and agree to Vermont First language in contract agreements.

4.

Track progress and growth in local food procurement.

5.

Sponsor an annual summit meeting and two working group sessions around

“scaling up” local food growing and procurement.

Relationship Building

6.

Collaborate with Vermont partners to understand which local foods the marketplace wants to procure.

7.

Develop a unique database for purchases from local producers and processors.

8.

Collaborate with distribution companies to share suppliers of local products.

9.

Organize an annual matchmaking event for producers, processors, food hubs and technical service providers.

Producer Investment

1.

Sodexo will develop a plan to meet the production needs of Vermont farmers and enable businesses to buy local. This includes market analysis, technical assistance around production, processing and marketing. A steering committee will be convened of Vermont stakeholders to discuss issues of procurement, marketing and meeting cutover demand.

Long Term Approach

Sodexo will help Vermont develop a “Vermont First” brand through favorable financing, investment opportunities and growing contracts through distribution.

The company has even discussed with its partners the possibility of establishing a producer co-operative specific to Vermont.

Contact info:

37

Abbey Willard

Local Foods Administrator

Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets

116 State St.Montpelier, Vermont 05620-2901

Tel: 802-272-2885

Email: abbey.willard@state.vt.us

http://agriculture.vermont.gov/

Appendix C: Graphical representation of Benchmark College’s current emissions

Green Mountain College: Growth over Time

850 500000

800

750

700

650

600

450000

400000

350000

2007 2009 2011 2013

4

3

2

1

7

6

5

0

-1

-2

-3

Green Mountain College:Net Emission Ratios

In Metric Tons of CO

2

2007 2009 2011 2013

8

6

4

2

14

12

10

0

-2

-4

-6

38

Middlebury Collge: Growth over Time

2800

2700

2600

2500

2400

2300

2007 2010 2013

2580000

2560000

2540000

2520000

2500000

2480000

2460000

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Middlebury College: Net Emission Ratios in Metric Tons of CO

2

2

0

14

12

6

4

10

8

2007 2010 2013

12500

12000

11500

11000

10500

10000

9500

9000

2007

University of Vermont: Growth over Time

6000000

5800000

5600000

5400000

5200000

5000000

4800000

4600000

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

39

University of Vermont: Net Emission Ratios

In Metric Tons of CO

2

10

8

6

4

2

0

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Appendix D: Existing Locations of water fountains on-campus

Buildings

Ware Student Centre

Sodexo

Colgate

Baird

Library

Hogan

Ivy

Mercer

Reichold

Total

Number of fountains

2

6

1

0

2

4

2

2

1

20

10

5

0

20

15

40

Appendix E: Water Fountain Unit description

Filtered EZH2O® Bottle Filling Station with Single ADA Cooler

Cost Price: $1,425

Specifications:

The Elkay EZH2O Bottle Filling Station delivers a clean quick water bottle fill and enhances sustainability by minimizing our dependency on disposable plastic bottles.

Complete cooler and bottle filling station in a consolidated space saving ADA compliant design

Bottle Filler features sanitary no-touch sensor activation with automatic 20-second shut-off timer

Quick Fill Rate

Green Ticker™ counts the quantity of bottles saved from waste

Expected Life span: at least 15-20 years

41