The Research Paper: What it Is and Why We Should Still Care Doug

advertisement

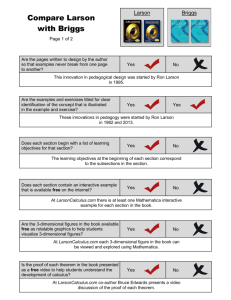

1 The Research Paper: What it Is and Why We Should Still Care Doug Brent Version presented to the Canadian Association for the Study of Discourse and Writing May 2012 Note: This is a considerably truncated version of a longer paper currently beimg prepared for publication. -In 1982, Ford and Perry found that something called a “research paper” was required in 85% of first year composition course. In 2009, Meltzer found that the research paper was still the single most prevalent form across all disciplines. However, the research paper seems to go by a variety of names, including “library paper,” “source paper” or even more vaguely, “term paper” Two things seem clear: 1. Students regularly have to learn to deal with something vaguely called the “research paper.” 2. When we use the term “research paper,” we don’t always seem to know quite what we are talking about. In order to get a better grip on what we are talking about, I intend to survey over thirty years of research and polemic on the subject. I’ll certainly touch on pedagogy, but I’m really more interested here in questions of definition and teleology that are logically prior to pedagogy. I’ve broken this presentation down into a set of questions about the research paper. What is it? Why is it important? Why should we worry about it as writing teachers? How do we help students with it? Part One: What is it? Any attempt to get a grip on the research paper seems to have to start with Richard Larson. In 1982, Larson published what has to be the single most frequently cited argument about the 2 research paper in a polemical article titled “The Research Paper: A Non-Form of Writing.” One might ask why I am dredging up an article from the early eighties; the answer is that Larson’s article refuses to go away, and is still cited as an argument against including the research paper as a genre in writing courses. This is a sure sign that Larson has hit on a major conceptual issue with the genre, one that continues to need addressing. Larson argues, The "research paper" has no conceptual or procedural identity. Research, while it can inform almost any type of writing, is itself the subject—the substance—of no distinctly identifiable kind of writing. . . . There is nothing of substance or content that differentiates one paper that draws on data from outside the author's own self from another such paper. (813) Here, Larson is defining “research” as any “data from outside the author’s own self.” By that definition, almost anything is research. As a result, the term “research paper” is so big and baggy that it’s not useful. I have to say that I agree completely on the problem. However, I don`t agree with Larson`s remedy, which is to dismiss the concept entirely. Rather, we need to find a better way of describing what it is. A genre exists if we think it does. That is, as Miller pointed out decades ago, as soon as people recognize that some sort of rhetorical exigence keeps coming up in ways that demand a similar response each time, we have a genre. The prevalence of the “research paper” as a form suggests that people throughout the academy recognize that there is some kind of repeated exigence here, but it doesn’t seem to refer to any kind of “research” in the ways that Larson means. Rather, what people generally mean when they say “research paper” is a paper that depends largely or exclusively on secondary sources arranged and integrated into the author’s text according to a varied but relatively stable set of conventions. The repeated rhetorical exigence, then, is the need to figure out how to internalize and respond explicitly to other texts, often written by people with much more expertise than the students. What Larson really tells us is that “research paper” is a clumsy name for this genre. In fact, while the term is still very much around, it is beginning to drop out of serious literature on the subject in favour of terms that more accurately reflect what the student it up against. In the late 1980’s, Linda Flower and a large group of researchers at Carnegie-Mellon and UC Berkley turned serious attention to the subject in the first co-ordinated and sustained way. In the string 3 of articles and technical reports they produced, they seldom if ever used the term “research paper.” Rather, they used terms such as “Reading to Write” and “Writing from Sources.” The biggest advantage of these terms is that it switches attention from what the form is to what the writer does. This is probably the single most important step in making the commonsense notion of the “research paper” into something more useful. If we stop worrying so much about the form of the research paper, we can start seeing it more as a set of activities which are quite distinct from producing writing based on personal experience, primary observation, or empirical research. This directs us to a whole different set of questions around what students or expert writers do. How do they select and interpret the sources they find? How do they construct a more or less original argument informed by those sources? More subtly, how to they avoid being overwhelmed by sources? It’s just plain harder, or at least really different, to base writing on the words of others rather than on the world. Those other damned words just keep getting in the way. Part Two. Before we start trying to answer these questions, we need to move on to Part Two: why is it important – or, as the second part of my title puts it, why should we still care? Maybe the answer is obvious: of course we care. However, the question is worth unpacking a bit, as it leads us to think about what a post-secondary education is for. In 1982, in the same issue of CCC that printed Richard Larson’s article, Schwegler and Shamoon interviewed instructors and students to ask what they thought about the purpose of the research paper. Not surprisingly, the students had limited and unclear views as to the purpose of the form. The instructors, however, were more explicit that the purpose was “to get students to think in the same critical, analytical, inquiring mode as instructors do—like a literary critic, a sociologist, an art historian, or a chemist” (821). This argument is similar to the one articulated by David Bartholomae in “Inventing the University.” It makes a lot of sense to see students as legitimate peripheral participants in the business of the academy, slowly picking up academic habits of mind by doing junior versions of what academics do. However, there are a couple of complications. The first is more or less aesthetic. Do we really want to define our role as academics as turning out little copies of ourselves, more academics ready to do more academic things – including 4 possibly educating still more academics? That description is disturbingly close to a description of a virus. The other complication is more practical. Even in research universities, relatively few students go on to be sociologists, art historians or chemists in the literal sense of going on to graduate school and immersing themselves in a research career. What is the role of learning to write from sources in the education of the other 90% of students? The answer here is to look at the larger context of the attitude cited by Schwegler and Shamoon. I don’t think the people they interviewed are just speaking of cranking out more sociologists, art historians and chemists. They are speaking of thinking “in the same critical, analytical, inquiring mode as instructors do.” Presumably, thinking in the same critical, analytical, inquiring mode as a sociologist does is intrinsically valuable whether one becomes a sociologist or not. This is version of the argument can be traced back to developmental psychologists like William Perry. Underlying these developmental perspectives is a belief that a liberal education should help students progress through stages of intellectual and epistemological development marked by increasingly complex engagement with the ideas of others. This does not just mean hearing and reading the ideas of others. It means fully engaging with them and making them do some work for you as a foundation for your own beliefs. The complexity and messiness of grappling with source texts is an important way of developing this intellectual complexity. Part Three. This brings me to part three – granted that it’s important for students to learn to write from sources, what’s our role in the process as writing teachers? There are some very good arguments for sending the matter of writing from sources, as well as writing in general, back to the disciplines where it arguably belongs. Joseph Petraglia and others have been called, not usually unkindly, the “new abolitionists” for their stance, also based in activity theory, that the composition course is a sterile environment in which to teach anything because writing and thinking is not generalizable from one environment to another. To be fruitful, it must be situated in the practices of a particular disciplinary discourse. I dealt with the matter of transfer in more detail last year, and in a couple of articles in JBTC and CCC. I’ll take the liberty of summarizing the whole matter of transfer by suggesting that there’s more to it than meets the eye, and that there is good reason to believe that rhetorical knowledge learned in one environment really does form a sound basis for reapplication in another. But just saying that transfer is possible is not the same as saying that our courses offer 5 a particularly fertile ground for teaching students to write from sources. To make that next claim, I need to jump ahead to Part Four of this presentation and explore just how motherbleeping difficult it is to learn and to teach writing from sources. Part Four – what are students up against? To underscore what students are up against, let me put aside the mountain of research that has accumulated over the past thirty years and pick two studies that anchor both ends of this time continuum. In 1988, as part of the Carnegie-Mellon and UC Berkley studies I mentioned earlier, Nelson and Hayes studied novice and advanced students writing from sources. They note two very different sets of strategies. “Low-investment strategies” involved the familiar pattern of waiting until the last minute and then quickly finding a few sources that contain “easily plundered pockets of information” (5). In contrast, “high investment strategies” involved broader information-seeking followed by writing a paper that constructs a complex argument around an issue. Although novice writers in the sample used low-investment strategies more often than the more experienced writers, the writer’s level of experience only partly predicted which set of strategies she or he would choose. In fact, one senior student reported being able to choose between the two strategies based on how important she thought the assignment was to her. What seemed most strongly to predict the strategies chosen was the structure of the course itself. Students given a topic and left to fend for themselves were more likely to choose lowinvestment strategies. They were more likely to use high-investment strategies when instructors broke the task into portions and provided feedback on each portion. Requiring drafts, response statements, log entries, and oral reports to classmates increased students’ sense that the assignment was a dialogue rather than a simple task of evaluation. In short, students’ willingness to invest in an assignment is proportional to the instructor’s willingness to make a similar investment. A much more recent study comes as the first fruit of Rebecca Moore Howard’s Citation Project. The Citation Project is the largest collaborative study of writing from sources since the Carnegie-Mellon/UC Berkley project in the eighties. (If you haven’t seen it, just google “Citation 6 Project.”) The Citation Project situates itself as an attempt to learn more about how students use sources in order to help prevent plagiarism. I find this a rather unfortunate place to start, but the use of sources is inextricably bound up with the misuse of sources, and the Citation Project group does manage to stay with descriptive research rather than sliding into moralizing. The proposed massive data collection is at an early stage, but a pilot article has been produced, and its message is disturbing. Common wisdom usually divides the use of sources into two types: paraphrase and quotation. Howard, Serviss and Rodrigue divide the use of sources into four types: copying, patchwriting, paraphrase and summary. They argue that summary consists of restating large portions of the original text, and sometimes an entire text, in fewer words. This is the form of writing from sources that is most valued in academic work as it implies comprehending and digesting the gist of a text and then using it as part of a larger argument. Disturbingly, in the eighteen sample papers they studies, Howard, Serviss and Rodrigue found no instances of summary. Instead they found various forms of copying, patchwriting and paraphrase in which only tiny portions of the original text were pressed into service in students’ texts. In fact, they argue that “these students are not writing from sources; they are writing from sentences selected from sources.” Howard, Serviss and Rodrigue take this as evidence that the problem originates before the act of writing from sources, in the prior act of comprehending sources. When students have a slender grip on what they’re reading and why they’re reading it, they are more apt to cherrypick a few sentences that seem to bear on their topic rather than applying the meaning of the whole text. In fact, Howard, Serviss and Rodrique cite Roig’s study that suggests even professors sometimes resort to patchwriting when asked to restate a difficult source from an unfamiliar field. These two studies bring me back to the question of why we in writing studies specifically should still care, and should still find ways of incorporating writing from sources into our courses. Both suggest in their own way that instruction in using sources is a big job that must be broken into smaller tasks and pulled through an entire course, or even better, a succession of courses, if it is to be successful. Moreover, we have to incorporate instruction in how to read sources as well as in how to write from them. Instructors in the disciplines have a major advantage over us in that, at least when dealing with majors, their students are likely in possession of more of the disciplinary knowledge that is fundamental to comprehension. On the other hand, we are better positioned to avoid what I 7 call “the anxiety of coverage.” An instructor in a disciplinary course may feel an immense pressure to cover a certain amount of material in order to provide students with the secure foundation of knowledge that they will need to pursue higher-level courses in the discipline. For us, subject area knowledge is to some extent gravy. We can spend a great deal of time working students through various phases of getting to know source texts, understanding how they relate to their own ideas, and drafting and revising various pieces of writing based on those texts, in ways that only the most dedicated instructor of a disciplinary course will feel able to do. Ideally, then, what we need are courses that focus on writing from sources in the context of a writing program, combined with a robust WAD/WID program that allows students to put their rhetorical knowledge to work in disciplinary contexts. That is certainly old news to everyone here. But what I am really trying to advocate is that, when we do turn our attention to writing from sources, we make it the focus of entire courses and not just portions of courses. I can remember, in my misspent youth, assigning a wide variety of writing tasks in a first year course, of which a “research paper” was just one. My disappointment with the results and my conviction that there has to be a better way to do this has propelled me on a career-long journey to understand what this familiar assignment really entails. The first-year seminar is one obvious way to make writing from sources a central feature that is drawn through an entire course. Another is the increasingly popular writing-about-writing approach that uses the study of writing itself as a “content area” that students can explore, read about and write about consistently throughout an entire course. Mostly I just want to argue that learning to write from sources is not just one of many writing tasks that students face in the academy. It’s absolutely fundamental to the academic mission itself, a sort of “master genre” that needs to be at the very centre of what we do. 8 Bibliography: Works cited in, or relevant to Doug Brent, “The Research Paper: What it Is and Why We Should Still Care” CASDW 2012 Bartholomae, David. “Inventing the University.” When a Writer Can’t Write: Studies of Writer’s Block and Other Composing-Process Problems. Ed. Mike Rose. New York: Guilford, 1985. 134-65. Ballenger, Bruce. Beyond Note Cards: Rethinking the Freshman Research Paper. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook, 1999. Brent, Doug. Reinventing WAC (again): The First Year Seminar and Academic Literacy. College Composition and Communication 57.2 (2005): 253-276. ---. “Transfer, Transformation and Rhetorical Knowledge: Insights from Transfer Theory.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 25.4 (2011): 396-420. ---.. Crossing Boundaries: Co-op Students Re-Learning to Write. College Composition and Communication“(Forthcoming, 2012). The Citation Project. http://site.citationproject.net/ Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. “Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies.’” College Composition and Communication 58.4 (2007): 552-84 Fister, Barbara. “Teaching the Rhetorical Dimensions of Research.” Research Strategies 11.4 (1993): 221-219. ---. “The Research Processes of Undergraduate Students.” Journal of Academic Librarianship 18.3 (1992): 211-19. Flower, Linda, et al. Reading to Write: Exploring a Cognitive and Social Process. New York: Oxford UP, 1990. Ford, James E., Sharla Reese, and David L. Ward. "Selected Bibliography on Research Paper Instruction." Literary Research Newsletter 6.1-2 (1981): 49 65. Ford, James E., and Dennis R. Perry. "Research Paper Instruction in the Undergraduate Writing Program." College English 44.8 (1982): 825 31. Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts. Logan: Utah State Univeristy Press, 2006. Howard, Rebecca Moore, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigue. “Writing from Sources, Writing from Sentences.” Writing & Pedagogy 2.2 (2010): 177–192. Keefer, Jane. “The Hungry Rats Syndrome: Library Anxiety, Information Literacy and the Academic Reference Process.” Research Quarterly 32.3 (1993): 333–39. Larson, Richard L. "The 'Research Paper' in the Writing Course: A Non Form of Writing." College English 44.8 (1982): 811 16. 9 Leckie, Gloria J. “Desperately Seeking Citations: Uncovering Faculty Assumptions about the Undergraduate Research Process.” Journal of Academic Librarianship 22.3 (1996): 20108. Manning, Ambrose N. “The Present Status of the Research Paper in Freshman English: A National Survey.” College Composition and Communication 12.2 (1961): 73-78. Melzer, Dan. “Writing Assignments Across the Curriculum: A National Survey of College Writing.” College Composition and Communication 62.2 (2009): 240-61. Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 70.2 (1984): 151-67. Nelson, Jennie. “This Was an Easy Assignment: Examining How Students Interpret Academic Writing Tasks.” Research in the Teaching of English 24.4 (1990): 362–96. ---. Constructing a Research Paper: A Study of Students’ Goals and Approaches. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Writing. Technical Report 59 (1992). http://www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/resource/680. ---. (1993). “The Library Revisited: Exploring Students’ Research Processes.” Hearing Ourselves Think: Cognitive Research in the College Writing Classroom. Ed. Ann M. Penrose and Barbara M. Sitko. New York: Oxford UP, 1993. 102-122 ---. “The Research Paper: A ‘Rhetoric of Doing’ or a ‘Rhetoric Of The Finished Word’”? Composition Studies: Freshman English News. 22.2 (1994): 65–75. Nelson, Jennie, and John R. Hayes. How the Writing Context Shapes College Students’ Strategies for Writing from Sources. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Writing. Technical Report 16 (1988). http://www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/resource/602. Perry, William G., Jr. "Cognitive and Ethical Growth: The Making of Meaning." The Modern American College. Ed. Arthur Chickering. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1981. 76-116. Petraglia, Joseph. ed. Reconceiving Writing, Rethinking Writing Instruction. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1995. Rabinowitz, Celia. “Working in a Vacuum: A Study of the Literature of Student Research and Writing.” Research Strategies 17.4 (2000): 337-46. Roig, Miguel. “Plagiarism and Paraphrasing Criteria of College and University Professors.” Ethics & Behavior, 11:3 (2001): 307-323 Schwegler, Robert A., and Linda K. Shamoon. “The Aims and Processes of the Research Paper.” College English 44.8 (1982): 817 24. Wardle, Elizabeth. “‘Mutt Genres’ and the Goal of FYC: Can We Help Students Write the Genres of the University?” College Composition and Communication 60.4 (2009): 765-89. ---. “Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study.” Writing Program Administration 31.1-2 (2007): 65-85.