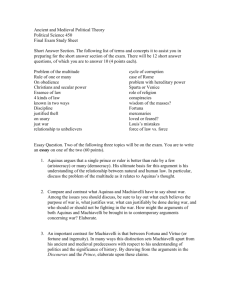

Aquinas and Natural Law Ethics

advertisement

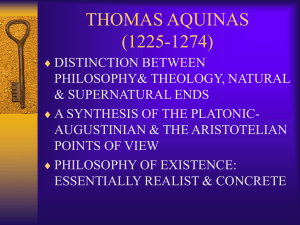

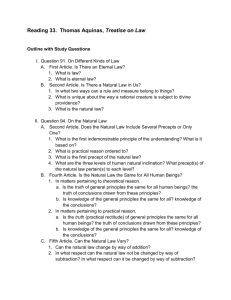

Aristotle + God Al-Farabi 870-950 CE Avicenna Anselm Averroes 980-1037 CE 1038-1109 AD 1126-1198 CE 900 Ockham 1287-1347 AD 1300 Al- Kindi 801-873 CE Al-Ghazali 1058-1111 CE *All images link to scholarly articles Maimonides Aquinas 1138-1204 AD 1225-12742AD Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) Aquinas was dubbed “the dumb ox” by his fellow students, for being large and quiet. He was apparently quiet because he was busy thinking; he became the Catholic church’s top theologian, a title he still holds today, without dispute. Aquinas’s major work, the Summa Theologica, is divided into 4 parts. Prima Pars (1st Part) Existence and Nature of God Prima Secundae (1st Part of the 2nd Part) Happiness, Psychology, Virtues, Law (Human, Natural, Divine) Secunda Secundae (2nd Part of the 2nd Part) The virtues in detail Tertia Pars (3rd Part) Christian Doctrine During the Middle Ages, many of Aristotle’s works were lost to Western Europe, beginning in the first few centuries AD. Aquinas merged Aristotle with Christianity after the recovery of his philosophy via Muslim scholars in the 12th and 13th century. The ‘purposiveness’ or ‘end-directedness’ of nature in Aristotle is identified by Aquinas with God’s purposes. Human nature determines what is ‘natural’ in ‘Natural Law’. God’s commands determine what is ‘lawful’ in ‘Natural Law’. Viewed from the human perspective, the principles of natural law are knowable by human nature and are structured to aid in furthering individual and communal goods. Viewed from God’s perspective, humans participate in the Eternal Law, which is God’s eternal plan— “A law is a rule of action put in place by someone who has care of the community” –Mark Murphy Aquinas’s first principle of morality is: Good should be done, and evil avoided We are by nature inclined toward the Good, according to Aquinas, but we cannot pursue the good directly because it is abstract—we must pursue concrete goods which we know immediately, by inclination. Those goods are: Preservation of life Procreation Knowledge Society Reasonable Conduct Aquinas, then, has a value-based ethical theory. The rightness or wrongness of particular actions is determined by how those actions further or frustrate the goods. Certain ways of acting are “intrinsically flawed” or “unreasonable” responses to these human goods. Like Aristotle, Aquinas seems sure there can be no formula provided to determine what action is right or wrong in all particular cases. Prudence (practical wisdom) is required for the most part, if not always, to determine if a given act is intrinsically flawed or not. Murphy provides a nice account of how acts can be intrinsically flawed or unreasonable: Aquinas does not obviously identify some master principle that one can use to determine whether an act is intrinsically flawed … though he does indicate where to look -- we are to look at the features that individuate acts, such as their objects …, their ends …, their circumstances …, and so forth. An act might be flawed through a mismatch of object and end -- that is, between the immediate aim of the action and its more distant point. If one were, for example, to regulate one's pursuit of a greater good in light of a lesser good -- if, for example, one were to seek friendship with God for the sake of mere bodily survival rather than vice versa -- that would count as an unreasonable act. An act might be flawed through the circumstances: while one is bound to profess one's belief in God, there are certain circumstances in which it is inappropriate to do so…. An act might be flawed merely through its intention: to direct oneself against a good -- as in murder …, and lying …, and blasphemy … -- is always to act in an unfitting way. –Mark Murphy http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natural-law-ethics/ Is an action ever intrinsically flawed because it fails to maximize goodness? Murphy, again: His natural law view understands principles of right to be grounded in principles of good; on this Aquinas sides with utilitarians, and consequentialists generally, against Kantians. But Aquinas would deny that the principles of the right enjoin us to maximize the good -- while he allows that considerations of the greater good have a role in practical reasoning, action can be irremediably flawed merely through (e.g.) badness of intention, flawed such that no good consequences that flow from the action would be sufficient to justify it -- and in this Aquinas sides with the Kantians against the utilitarians and consequentialists of other stripes. –Mark Murphy http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natural-law-ethics/ Must prudence determine the right action in every situation, or are there at least some universal general rules that are always valid or correct? And while Aquinas is in some ways Aristotelian, and recognizes that virtue will always be required in order to hit the mark in a situation of choice, he rejects the view commonly ascribed to Aristotle (for doubts that it is Aristotle's view; see Irwin 2000) that there are no universally true general principles of right. – Mark Murphy http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natural-lawethics/ Title Slide: Library, St. Paul’s College, Washington, D.C. http://www.flickr.com/photos/lricecsp/2365699386 The Good Analogy of the Sun Mind The Sun is… that makes… to the … through the power of… by providing … a visible object objects visible eye sight light The Good an intelligible object objects intelligible soul understanding truth The tree above is the visible object, the Forms (Universals) are the intelligible objects that the Good shines on. Both the Sun and the Good create their objects. http://www.boisestate.edu/people/troark/didactics/ancient/materials/Line_Sun.pdf The Good Substance Quality Place Quantity Relation Socrates is one is white is in Athens is a friend to Plato as a transcendental property Position Action Time Possession Passion is seated it is noon is speaking has a toga Is it odd that ‘good’ can be predicated in any of the 10 categories? is being spoken to The Great Chain of Being God = Being = The Good Angels Actuality Humans Animals Plants Rocks Potentiality Mud Nothingness Aquinas gets the chain from Plotinus (his student, Porphyry), Augustine, Boethius, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, and others, and adds to it Suppose there are 4 modes of existence: 1. Necessary 2. Actual 3. Possible 4. Impossible If a perfect being is possible, it must be actual, because it's more perfect to be actual than just possible. The argument succeeds. But there's more: if a perfect being is actual, it must be necessary, for the same reason ... it's more perfect to be necessary than just actual. SO ... a necessary being that is all good, all powerful, and all knowing, exists. Necessary beings can have no cause of their existence (except trivially themselves), and so it is confusion to ask who made God. God actually explains the existence of himself and everything else. Objection: But is ‘existence’ a real predicate? A feature a thing may have or lack? Response: It isn't claimed that there is a possible perfect being. It's just pointed out that a perfect being is possible, or ‘perfect being’ is contradiction free. Think of it this way: there are red things. For them to exist, there did not have to be possible red things capable of having or lacking the property ‘existence’. 'What it is to be red', though, had to predate red things. What it is to be a perfect being predates, logically, but not temporally, a perfect being. The argument is one of reason, not causation. Does that make sense? There's nothing contradictory about a perfect being if that being is a person (personal qualities admit of perfection, unlike physical qualities ... no such thing as a perfect island, for instance, because you can always add another nice palm tree or nubian maiden ... but personal qualities, like knowledge, power, and goodness, have intrinsic maxima ... they have upper limits which, when met, yield perfection of that quality.