as_the_geographic_territory_under_roman_control_grew

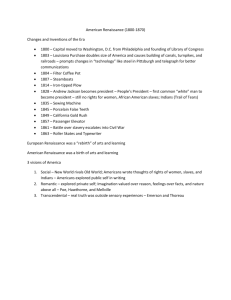

advertisement

As the geographic territory under Roman control grew, the use of Latin as a common language also spread. In areas under Roman control, Latin was the spoken and written language of the courts and commerce, as well as the language of the Christian church. As the Roman Empire expanded, Latin served as a common language that allowed for people of diverse linguistic backgrounds to be able to communicate. Latin, like other languages past and present, had more than one form and changed over time because it was both written and spoken, and the educational level or social status of the writer or speaker often determined the final form of the language. Latin was also influenced by local languages spoken or written within the larger territory under the influence of what later came to be known as the Roman Empire. During the Carolingian Renaissance, throughout the reign of Charlemagne and his successors, the development of Latin literacy was greatly promoted. Although reading and writing were skills that some people had, literacy was not widespread before that time. Literacy in Latin was generally limited to people of the upper classes and members of the clergy. Charlemagne invited Alcuin of York to become his personal tutor and the head of his court school. Charlemagne charged Alcuin with the development of a literacy curriculum for children that would provide for their instruction in reading and writing, as well as for further study in the liberal arts and theology, thereby also furthering the Christian teachings that Charlemagne’s court promoted. The promotion of literacy impacted education and language throughout the region. The demand for material relating to the interests of the ruling military class increased. Over time, vernacular languages, the languages commonly spoken, began to be used by writers. Until the 12th century, Latin was the primary language used by writers. French writers began the trend of using vernacular language in the 12th century, and by the end of that century, some government and legal documents in England and France were composed in the vernacular. In the 12th century, literacy among women was also increasing. Though literacy in Latin was still somewhat limited to specific social classes, literacy in local vernacular languages was increasingly common. Eleanor of Aquitaine established the city of Poiters as a center for a literary movement focused on the art of courtly love. The troubadour and the female counterpart, the trobairitz, used poetry to share stories of romantic longing and unattainable love. This poetry represents the beginning of written expressions of love in the way romantic love continues to be perceived today. It focuses on the feelings associated with romantic love: longing, suffering, loss of appetite, temptation, loyalty, and a desire to do whatever possible to have the feeling of love reciprocated. As the poetry of the troubadour or trobairitz was recorded, it was written in the vernacular of the day. In fact, the word romance derives from the word romans, the old French term for the vernacular language specific to the region. Having poetry and prose in the vernacular of the people allowed a much wider audience to access this romantic literature. By the early 14th century, the trend toward the use of vernacular language had spread throughout most of Europe. As monarchies throughout the region began to consolidate, the use of vernacular languages contributed to an increasing nationalism, or feeling of pride in one’s own nation, and in this case among people of similar linguistic backgrounds. People began to feel more connected to local leaders than they did to influences from afar. These sociopolitical shifts, along with the development of moveable type (the printing press), helped to ensure the success of the vernacular languages during the Renaissance. As the name implies, the Renaissance was a rebirth of culture and learning that took place in Europe over a period of several hundred years. Although it began in Italy during the 1300s and ended in the late 1500s, it also spread northward, where it peaked in the 16th century before dying out in the mid-1600s in that area. During this period, scientific and geographic discoveries were championed. It was discovered by Copernicus that the sun was the center of the solar system and the planets, including Earth, orbited the sun. Exploration of new trade routes gained the support of ruling families. Major changes to the longstanding authority of the Catholic Church were brought about by challenges made by Martin Luther during this time. The works of one of the best-known writers, William Shakespeare, were composed and presented in England. The Renaissance was a time in which the various possibilities for human expression and discovery within the world were championed. Humanism is defined by Sayre (2010) as “the recovery, study, and spread of the art and literature of Greece and Rome, and the application of their principles to education, politics, social life, and the arts in general” (p.185). It provided the philosophical backbone of the Renaissance and reformation in Europe. With a renewed sense of interest in ancient cultural roots and traditions, the people of the Renaissance in Europe desired a separation from the more recent medieval past. This recent past was perceived as a period of less cultural value, and the reliance upon religious texts and sacred traditions that had proven integral to the medieval period lessened in importance. An appreciation for self-determination—the ability of the individual to choose his or her path—lead to a greater value being applied to human life. The importance of the individual within society was acknowledged. Some individuals who had the ability to do so financially served as patrons, supporting the work of writers, artists, and other artisans during this period. Reference Sayre, H. M. (2010). Discovering the Humanities. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall-Pearson. Imagine an illness so powerful that people who go to bed healthy do not live until dawn. It kills up to 95% of the people exposed to it, depending on the particular strain. Imagine a plague that kills an estimated 35% of the entire population of Europe in a matter of three short years (Cartwright, n.d.). Now imagine that you are living in the Middle Ages. Modern medicine does not exist, modern means of communication are not available, modern transportation options have not been developed, and modern scientific processes that could explain where the disease comes from and how it is transmitted are beyond the horizon. This is the situation in which the people of Europe found themselves in the mid 1300s, as the plague that became known as the Black Death began its decimation of the continent. Bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, was an often deadly disease introduced to Europe that was carried by fleas and rats. There were distinct forms of the plague, but bubonic was the most commonly seen and therefore lent its name to the epidemic as a whole. The name itself comes from the swelling and blackening of the lymph glands of the groin, armpits, or neck of the infected individual. These black lumps were known as buboes. The infected person might also carry the disease in the bloodstream, resulting in the septicemic version of the plague. These forms of the illness were fatal most of the time. The third subtype of the plague, pneumonic, was the most deadly, taking the lives of nine of every ten of those afflicted. The plague, in its various forms or phases, caused the telltale boils, which could ooze pus and blood, and also caused a fever, chills, vomiting, general malaise, or respiratory ills manifested through coughing and sneezing. Physical contact with an infected individual’s bodily fluids could also pass on the disease. From late 1347 until 1350, the Black Death ravaged Europe. It was most active in the spring, summer, and fall months and less active in the cold winter months, and people of all ages were affected. Children, the elderly, women, men, and otherwise healthy individuals were at risk of infection. The plague took the lives of more than 60% of the inhabitants of some cities (Sayre, 2010). Peasants were found dead along roadsides, and ships washed ashore when their crews perished at sea. Florence lost 4% of its population in a two-day period (Ibeji, 2010). In many cases, the deaths also came many at a time. Entire streets or families would succumb to the illness seemingly overnight. Historical records from the time are not complete, so determining an exact number of victims is not possible. However, many estimates put the death toll at or above 25% of the European population during the height of the plague years alone (Kreis, 2000). All of Europe was impacted. No one could be assured of being spared. Much of this was due to the fact that people did not know how the disease was spreading, and they did not take basic precautions that would be encouraged in modern times to stop or slow the spread of disease. The Black Death was carried by rats and fleas and transmitted by the bites of these animals. Although rats and fleas are not part of modern daily life for most, in the fourteenth century, these creatures were part of day-to-day existence. Records show that there had been rumors of a plague sweeping through areas to the east in the years before it came to the European continent, but relatively little attention was paid to the tales. It is widely believed that the disease first appeared in Europe when ships coming from trading ports on the Black Sea returned to Genoa, Italy in 1347. Fleas, once their rat hosts died, would feed on other nearby mammals. In the case of rats on ships, the sailors became the victims. As the rats and their fleas literally jumped ship in Genoa, the plague began a reign of terror that lasted beyond the initial, and most deadly, three-year period. Small outbreaks of the plague continued to hit pockets throughout Europe for many years to come. The people of Europe did not know how disease was spread or what precautions to take to reduce its spread. Hand-washing and frequent bathing were not commonly encouraged practices until the last century. Isolating oneself from the general public or large gatherings during times of disease was also an unknown practice, as it relates to reducing one’s exposure to disease. Likewise, isolating the ill from the well, and ensuring that the well did not come into contact with bodily fluids of the ill were not common practices. The treatment of the dead and the handling of corpses were also different from what is done in modern practice. The lack of knowledge about how the disease was transmitted and what could be done to slow or stop the spread contributed to the great number of deaths. The impacts of the Black Death were many and varied. The initial decimation of the European population lead to a significant, but short-term reduction in crop production. This also resulted in a decrease in the foods available at the market. It is also reported that animals were likely affected by the plague. Some reports note entire flocks of dead sheep in the fields. However, with fewer people for whom food needed to be produced, this temporary decrease was soon made up for as the remaining population took over the farmland of those who had perished. Time-honored traditions of succession and land tenure were interrupted. The land-owning nobles, accustomed to collecting significant amounts of dues either in the form of crops or cash payments, had fewer serfs on whom to depend for payments. This decreased their power to demand payment for the privilege of working the nobles’ lands. Eventually, serfdom was replaced by a system in which the landowners paid those who worked their lands. The sociopolitical structure that had existed prior to the plague underwent significant changes. Another effect of the Black Death was an increase in university enrollments at institutions where medicine was a field of study. Students who had seen the effects of the plague and survived brought with them new ideas about how diseases could spread or how they might be treated. At this time, there was also a push for the translation of major medical texts into vernacular languages from the more traditional Greek or Latin presentations. References Cartwright, F. F. (n.d.) The Black Death. Retrieved from http://www.insectainspecta.com/fleas/bdeath/Black.html Ibeji, M. (2005). British history in depth: The Black Death. Retrieved from the BBC Web site: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/black_01.shtml Kreis, S. (2000). Satan triumphant: The Black Death. Retrieved from History Guide Web site: http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/lecture29b.html Sayre, H. M. (2010). Discovering the humanities. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. The Middle Ages The Middle Ages span the fall of Rome in the 5th century and last through the 15th century. Often called the Medieval Era, the Middle Ages are often divided into the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages. The Early Middle Ages are characterized by sparse populations and basic agricultural cultivations. In contrast, the High Middle Ages (1000–1300 CE) are characterized by population growth, urbanization, and commercial expansion facilitated by agricultural expansion and production that supported such growth. Finally, the Late Middle Ages are characterized by the destruction and loss of the spread of the Black Plague that devastated Europe in the 14th century, resulting in the loss of between one quarter and one half of the population (Spielvogel, 1999). Starting in Constantinople in 1347 CE, the Black Death (now known to be bubonic plague) produced a near collapse of the economic and social systems throughout Europe, resulting in the destruction of trade and commerce and in some instances entire villages or communities. Bubonic plague was spread by the fleas that were found on black rats. The damage it did throughout Europe was enormous in terms of the loss of life and the overall destruction of economic, social, and political systems (Levack, Muir,Veldman, & Maas, 2007). In the era that followed the spread and devastation of the plague, Europe experienced a remarkable recovery that would produce the contours for what today represents the foundation of Western civilization. The Renaissance Following the destruction wrought by the spread of the Black Death in the 14th century, Europe experienced a remarkable resurgence that is characterized by a flourishing of cultural, economic, and political expansion. Centered in Italy and then spread throughout the remainder of Europe, the focus of the Renaissance (or rebirth) would result in the remarkable expansion of the West that would produce global exploration and expansion by the 15th century. The explosion of artistic and technological innovations and expressions that characterize the Renaissance include the works of artists like Michelangelo and Rafael, the political philosophies of Machiavelli, the religious thoughts of Martin Luther, and the scientific breakthroughs of Leonardo da Vinci and Galileo (Spielvogel, 1999). Indeed, the influence of the Renaissance resonates today because the Renaissance as an era is considered to mark the birth of modern civilization. From the Renaissance comes the foundation of modern education with a curriculum that focuses on a breadth and depth of critical inquiry and emphasizes well-rounded courses of study (Levack et al., 2007). Specifically, there was a focus on creating well-rounded people who have the ability to contemplate and master the world around them (Spielvogel, 1999). The legacy of the Renaissance remains visible today with the continued emphasis in education and an effort to try to understand the world around us through contemplation. References Levack, B. P., Muir, E., Veldman, M., & Maas, M. (2007). The West: Encounters and transformations. New York: Longman. Spielvogel, J. J. (2000). Western civilization. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Question 1: What sorts of labor systems were employed by the Spanish colonists? Answer 1: The first system was the institutional labor system. The encomienda or the entrustment required the Spanish encomendero to instruct the Indians entrusted to him in the Christian religion, in the various elements of European civilization, and required him to defend and protect the Indians. In return, the encomendero could demand tribute and labor from them. The second system was the repartimiento, and it replaced the encomienda. This system allowed for the temporary allotment of Indians workers for a given task. Under this institution, royal authorities, in effect, controlled and parceled out Indians for a specific task. The third system entailed the grouping of Indians into aldeias, or villages, where they could be introduced to Christianity and European civilization more easily. In return for this favor and their protection, the Indians gave a portion of their labor to the Church and state. Finally, the fourth labor system evolved after the Jesuits spoke out to protect the Indians after their arrival in the New World in 1549. In a progressive step, and to ensure a more dependable labor system, Indians were contracted as wage laborers. The practice, however, was quickly corrupted and soon the hacendados, established a system where loans were made to Indians that were to be repaid with labor. Of course, the labor never seemed to suffice to pay off the loan, and it was passed from father to son(s). Question 2: What were some of the natural resources found in South America? Answer 2: The natural resources of South America included gold, silver, precious stones, sugar, Brazilwood, indigo, cacao, coffee, tobacco, hides, fruits, rum, cotton, lumber, various minerals and metals, chicle, textiles, wheat, corn, rice, as well as a variety of drugs found in the vast rain forests. Large ranches were also developed on which where cattle, horses, sheep, and goats were raised. Question 3: What was the role of the Church in settlement? Answer 3: The task of the Church in exploration was to evangelize the Indians. This mission, however, was more than just converting them to Christianity. The missionaries would also be “Europeanizing” them by teaching the Indians trades, customs, language, manners, and Iberian habits. The goal was twofold, to offer them eternal salvation and to make them royal subjects to the empire. In order to deal with the Indians more efficiently, the Indians were grouped into small communities or villages. They learned and practiced their trades and behaved as Iberians. The village structure helped the Iberians to maintain control over territories and defend against invasion. The Church also provided job opportunities for women outside of the home. The actions of the Church can be interpreted differently depending on the situation and personal viewpoint. Question 4: How did the Iberian monarchs feel about the treatment of the Indians? Answer 4: As opposed to today, the Church and state were virtually inseparable. The monarch received his/her legitimacy and authority to rule through the recognition of the Catholic Church. Religious leaders in the New World were often the representatives of the Indians and petitioned the Church to get involved when Indians were suffering ill treatment from the Iberians. The missionary or the Pope would then turn to the monarch and appeal for better laws protecting the Indians. Isabel, for instance, expressed sincere concern over the welfare of the Indians and warned the Spaniards to treat them well but could not enforce punishment for abuses of the policy because of the sheer distance between Spain and the New World. In order to receive papal (from the Pope) approval of Iberian territorial claims, however, the monarchs were charged with the responsibility of converting the Indians to Christianity, civilizing them, and protecting them. King Ferdinand passed the Laws of Burgos in 1512, which was the first general code for the government and instruction of the Indians. It stipulated the humane treatment of the Indians and thereby limited and supervised the power of the encomiendero.