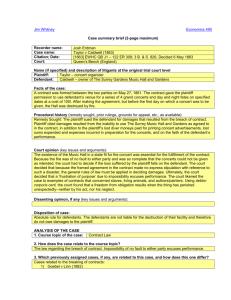

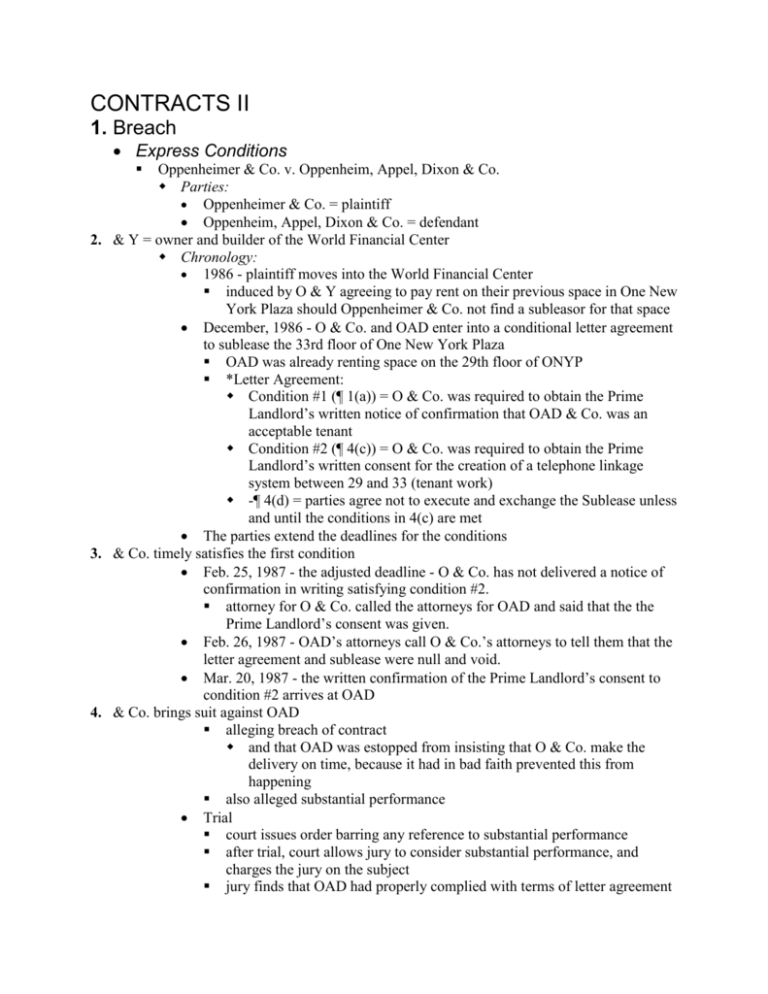

CONTRACTS-II-ta - Law Office of Ciara L. Vesey, PLLC

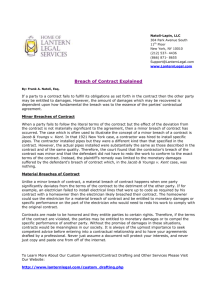

advertisement