Principal Determinants of Consumption (Slide 1)

advertisement

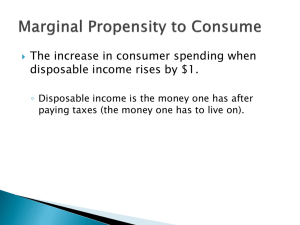

Chapter 4 The Consumption Function Principal Determinants of Consumption (Slide 1) • • • • • Recent average disposable income (DI) Expected average DI Changes in income tax rates Cost and availability of credit Demographic factors and age distribution of consumers Principal Determinants of Consumption (Slide 2) • Expected rate of return on assets: debt, equity, and real estate • Changes in spendable income not included in DI caused by fluctuations in asset prices • Exogenous shifts in consumer attitudes not related to any of the above variables Recent Average Disposable Income (DI) • Income from All Sources • Wages, Income from Capital, and Transfer payments • Income and social security taxes are deducted, but not sales and excise taxes • Some income is not included, primarily from capital gains and home refinancing Expected or Average DI • Most people base their spending on average or expected income, rather than the most recent paycheck. This is usually known as the permanent income hypothesis. • A few examples: • You win the lottery, but you don’t spend all of it that month. • You become unemployed, but your consumption doesn’t drop to zero. • You save in anticipation of the children’s college education, then dissave during the years they are actually in college Changes in Income Tax Rates • This remains a politically charged issue, but most economists agree that: • A permanent change in tax rates has a larger impact on consumption than a temporary change. • Consumers are likely to spend a larger proportion of any tax cut if they are optimistic about the future • It is possible that while consumption rises because of a tax cut, imports also rise, so the net effect on real GDP is much smaller. Demographic factors and age distribution of consumers • The Life Cycle Hypothesis states that young people will dissave when they are just starting their careers, will maximize their saving rate shortly before retirement age, and then dissave again during retirement years. • That implies that the general aging of the population would reduce the personal saving rate. Cost and Availability of Credit • A key determinant, especially with the proliferation of credit cards, home equity loans, and other sources of borrowing. • Imposing actual credit controls has an immediate and drastic impact on consumer spending, but for that very reason probably would not be utilized again except in extreme circumstances. Excessive Credit Sensitivity • The PIH and LCH state that when income declines, consumption does not decline as much. Hence the personal saving rate would decline in recessions • However, we find empirically that the saving rate rises during recessions. • This is usually referred to as excessive credit sensitivity. Even if consumers plan to spend based on their permanent income, they may have to cut back if borrowing sources are diminished. This applies mainly to purchases of durable goods. Cost of Credit • Five possible reasons why the personal saving rate is positively correlated with interest rates. • When interest rates rise, people save more now so income and consumption can be higher later. • Average monthly payment rises, reducing demand. • Stock market declines • Housing prices rise less rapidly, so less home equity financing and refinancing • Yield spread narrows, so credit availability diminishes. Expected Real Rate of Interest • Argument is complicated by fact that when interest rates rise, it is usually because inflation rises, so the expected real rate of interest may not increase. • Suppose interest rates went from 5% to 15% at the same time that inflation went from 2% to 12% (as in the late 1970s). People would have no additional incentive to save. • As a result, this is the weakest empirical link between interest rates and the saving rate. Cost of Time Payments • This applies mainly to purchases of motor vehicles. • Higher interest rates raise the monthly time payment or lease payment substantially. • “Zero interest rate” financing boosted motor vehicle sales sharply even though the average reduction in the monthly payment was only about 2%, since low interest rates enabled manufacturers and dealers to absorb some losses on existing leases when consumers bought new motor vehicles. Changes in Stock Market • Of course stock prices depend on many factors other than interest rates, yet it is true that lower interest rates will lead to higher stock prices, ceteris paribus. • Since a rising stock market boosts consumption relative to disposable income, there is a positive correlation between the saving rate and interest rates for this reason. Impact on Housing Financing • Housing prices show a strong negative correlation with interest rates. • As rates decline, housing prices rise faster, so more homeowners can cash out some of this increased equity. • Lower interest rates also permit more people to refinance, hence reducing their monthly mortgage payment – which is not counted as part of consumption – and increase purchases of other goods and services. Yield Spread • The yield spread between long and short-term interest rates is a major determinant of consumer spending and total GDP. • Usually, long-term rates are higher than shortterm rates. However, when the reverse is true – known as an inverted yield curve – the U.S. economy has always headed into a recession the following year. • When the yield spread becomes inverted, banks will reduce the amount of loans made to consumers, hence diminishing purchases. Expected rate of return on assets: debt, equity, and real estate • If consumers expect the rate of return on assets to rise, they will generally spend a higher proportion of their income. That is particularly true for housing, where rising prices cause many people to “cash out” some of their increased equity. • A rising stock market generally leads to an increase in the ratio of consumption to disposable income Changes in spendable income caused by fluctuations in asset prices not included in DI • This has become an increasingly important factor in recent years. Capital gains are not included in disposable income even if they are realized. Thus during a rising stock market, part of the reported decline in the personal saving rate could be due to an increase in realized capital gains. • Also, many people cash out some of their increased equity when housing prices rise. • When interest rates decline, homeowners may refinance, hence boosting the amount of income they have to spend on other items. Exogenous shifts in consumer attitudes not related to any of the above variables • Consumers will spend a higher proportion of their income if they are optimistic about the future, and spend less if they are pessimistic. Virtually all economists – and retailers – agree with that statement. • However, measuring these exogenous shifts is often quite difficult, and economists have not been successful in anticipating these shifts. Which is More Important –Income or Credit ? • Both real disposable income and the cost and availability of credit are key determinants of consumer spending. • Most short-term fluctuations in consumption are related to changes in credit rather than income. • Temporary changes in tax rates do not affect consumption very much. Permanent changes are more likely to affect spending in the longer term. Impact of Consumer Confidence • Many business managers use the index of consumer confidence as a useful shorthand for how much consumers will spend in the near future. • The key determinants are: • Level of the unemployment rate • Change in unemployment rate • Change in rate of inflation • Change in stock market • Change in implicit wage rate (a measure of overtime and “good jobs”). How Useful Is It? • The index of consumer confidence accurately tracks the major changes in the ratio of consumer spending to income. • However, short-term fluctuations in this index, which are often tied to exogenous events such as wars, elections, and natural disasters, are not reflected in changes in consumer spending. • Conversely, very short-term changes in consumer spending often appear to be random in nature (weather, etc.) and are not tied to either economic or attitudinal variables.