Logical Fallacies

advertisement

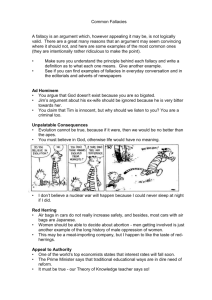

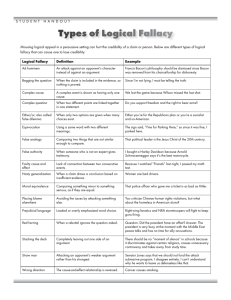

Logical fallacies are errors in the structure of an argument. “Fallacy” means falsehood. These arguments can be used to distract people from the actual issue or to persuade Although these arguments may sound persuasive and may seem correct, some part of the argument is flawed. Circular Reasoning: Supporting a claim with a reason that is simply a restatement of the claim itself “Abortion is murder because it is intentionally killing an unborn human being.” (Simply a restatement of the definition of “murder”) "If such actions were not illegal, then they would not be prohibited by the law." Example Red Herring: Introducing a side issue, irrelevant to your issue “I shouldn’t have to pay this parking ticket because there are a lot people committing violent crimes out there who should be locked up.” Example Straw Man: An oversimplified version of an opponent’s position that is easy to refute Ad hominem: Latin for “to the man,” this fallacy involves attacking the person who holds a position rather than the argument itself. "Senator Jones says that we should not fund the attack submarine program. I disagree entirely. I can't understand why he wants to leave us defenseless like that.“ Example “9/11 conspiracy theorists are crazy idiots.” Example Bandwagon: Asking readers to accept your claim because everyone else does, or many other people do. “Everyone agrees that marijuana should be legalized.” Example of Bandwagon AND Ad hominem Overstatement or sweeping generalization: An absolute statement usually involving “all,” “always,” or “never” statements, in which one exception will disprove the claim “All women want to get married and have a family.” “Democrats never support the Second Amendment.” Example Hasty or faulty generalization- An argument from insufficient evidence or from too small a sample. “Bullying doesn’t exist in this school because I have never seen it.” Slippery slope: The argument that if X happens, then Y and Z will surely follow, when there’s no clear connection between X, Y, and Z. “If we make assault rifles illegal, next they’ll want to outlaw hunting rifles, kitchen knifes, and heaven knows what else.” Example Either/or fallacy: Sometimes called a false dilemma, the argument that there are only two possible answers to a complicated question, one usually terrible. “If we don’t prohibit text messaging from our classes, then no one will learn anything in them.” “America: love it or leave it!” Example Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc: Latin for “after this, therefore because of it,” this is the classic error that assumes that simply because B followed A, B was caused by A. “Before women got the right to vote, there were no nuclear weapons.” Example #1 Example #2 Faulty analogy: The argument that because two things are alike in one respect, they are alike in other respects as well. "If advertising for tobacco becomes illegal, then we should outlaw advertising for milk and eggs because they contain cholesterol, a harmful substance.” “Jimmy gets to stay out until 1 a.m.—why can’t I?” Maybe because Jimmy is 19 and you’re seven? Example Non Sequitur: Latin for “it does not follow,” it’s applied to arguments in which the conclusions are not logically connected to the reasons The economy is one of our biggest problems because cake is fattening. Example Stacking the deck: Related to the hasty generalization, this is the argument that ignores or significantly downplays facts or evidence contrary to one’s position and highlights points that support it. A poster for the U.S. Army focuses upon an impressive picture, with words such as "Travel" and "Adventure", while placing the words "Enlist today for 2,3, or 4 years" at the bottom in smaller and less noticeable font. They also don’t mention that you will most likely deploy to a war zone soon after your training is complete. Appeal to Ignorance: A claim that whatever has not been proven false is true and vice versa.” “9/11 must be a government conspiracy because there is no convincing evidence that it wasn’t.” God exists because no one can prove He doesn’t. Pretend you disagree with the conclusion you're defending. List your main points; under each one, list the evidence you have for it. What parts of the argument would now seem fishy to you? What parts would seem easiest to attack? Give special attention to strengthening those parts. Seeing your claims and evidence laid out this way may make you realize that you have no good evidence for a particular claim. It also may help you look more critically at the evidence you're using. Learn which types of fallacies you're especially prone to, and be careful to check for them in your work. Some writers make lots of appeals to authority; others are more likely to rely on weak analogies or set up straw men. Read over some of your old papers to see if there's a particular kind of fallacy you need to watch out for. Be aware that broad claims need more proof than narrow ones. Claims that use sweeping words like "all," "no," "none," "every," "always," "never," "no one," and "everyone" are sometimes appropriate—but they require a lot more proof than less-sweeping claims that use words like "some," "many," "few," "sometimes," "usually," and so forth. Double check your characterizations of others, especially your opponents, to be sure they are accurate and fair.