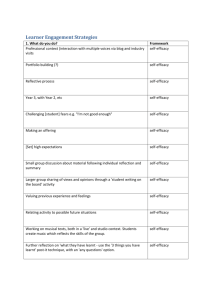

Teacher Self-Efficacy

advertisement