THE EFFECTS OF DIETARY FAT INTAKE ON RESTING ENERGY

EXPENDITURE AND BODY COMPOSITION

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Kinesiology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

in

Kinesiology

(Exercise Science)

by

Nichole Mi Hui Eytcheson

SPRING

2012

© 2012

Nichole Mi Hui Eytcheson

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

THE EFFECTS OF DIETARY FAT INTAKE ON RESTING ENERGY

EXPENDITURE AND BODY COMPOSITION

A Thesis

by

Nichole Mi Hui Eytcheson

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Roberto Quintana, PhD

__________________________________, Second Reader

Wendy Buchan, PhD

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Nichole Mi Hui Eytcheson

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format

manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for

the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Michael Wright, PhD

Department of Kinesiology

iv

__________________

Date

Abstract

of

THE EFFECTS OF DIETARY FAT INTAKE ON RESTING ENERGY

EXPENDITURE AND BODY COMPOSITION

by

Nichole Mi Hui Eytcheson

Statement of Problem

Whether changing from a high-fat diet to an isoenergetic, low-fat, high- complexcarbohydrate diet results in thermogenic benefits is controversial. Brief dietary

interventions and failure to account for the potential influence of body-fat distribution on

energy metabolism could have confounded the interpretation of previous studies. The

success of individuals who lose weight by changing from high fat diets to low-fat diets

has prompted numerous, well-controlled studies of this phenomenon. The literature

regarding a thermogenic effect of low-fat, high-CHO diets reveals conflicting evidence.

The present study was designed to answer the following questions; 1) Does dietary fat

restriction increase the caloric need to maintain weight? 2) Does lowering the fat intake

in the diet affect resting energy expenditure (REE)? 3) Does dietary fat restriction affect

body composition?

Methods

Sixty-four healthy post menopausal women were recruited to the study and enrolled

in four cohorts of 16 participants every 4 months. Each cohort went under 3 dietary

v

interventions over a 4 month period. Dietary intervention involved a 4-month long

eucaloric controlled-feeding that was designed to reduce the fat intake stepwise to 15% of

the daily energy intake. Bioelectrical impedance (BIA) was used to assess body

composition and provide values for FFM and FM. REE was collected using indirect

calorimetry and calculated using the Weir equation. Data were expressed as means +

standard deviations (SD).

Results

The four dietary interventions did not alter REE (p=.979). There was a trend for

an increased respiratory exchange ratio with the low-fat diet (p=.067). Although the

controlled-feeding phase was designed by calculated, computer generated analysis to

deliver 35%, 25% and 15% of the energy intakes from fat, laboratory and chemical

analysis of the diet showed that the actual dietary fat intakes were 31%, 23% and 14%

respectively. There was a significant difference in body weight (0.9 kg) between baseline

and after the 35% fat diet (p=0.0003), no significant change between the 35% and 25%

fat diet (0.05 kg, p=0.218), and no significant change between the 25% fat diet and the

15% fat diet (0.05 kg, p=0.156). During the eucaloric feeding as dietary fat decreased

from 31 % to 23% to 14 %, the energy cost of weight maintenance increased from

8724+1281 kJ, to 8946+ 1310 kJ, and to 9122+ 1365 kJ, respectively. These increases

were significant (+223+400 kJ, p< 0.02 and +398+638 kJ, p < 0.0001 ). There was a

significant decrease in body fat (kg), fat mass (kg), and fat free mass (kg) after the 35%

fat eucaloric feeding (p=0.033, 0.0008, 0.0001) respectively. There was no significant

vi

difference between the 25% fat (p=0.297, 0.224, 0.419) and 15% fat feeding (p=0.079,

0.147, 0.177).

Conclusions Reached

Our results demonstrate that restriction of fat intake increases the energy cost of

weight maintenance (ECWM), has no effect on REE or RER, and caused small

differences on FM, FFM, and BF. Given the evidence that carbohydrate is 25% less

efficiently utilized by the body, one could speculate that a person could consume 25%

more calories in CHO than fat without gaining weight. While the study also failed to

demonstrate any change in REE, this suggests that the increase in energy expenditure

must likely occurs post-prandially. While the study controlled for body composition

using a eucaloric diet, decreases in FFM, FM, and BF were observed. In summary, the

present study supports that low-fat intake increases the ECWM and reduces body lipid

stores. It appears that low-fat intake can improve risk factors for coronary artery disease,

such as dyslipidemia, decreases risk of diabetes and obesity, and results in weight loss

without food deprivation. Therefore, it seems prudent to suggest restriction of dietary fat

especially in an obese post-menopausal female population.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Roberto Quintana, PhD

_______________________

Date

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank and acknowledge not only the people who helped me to

complete this thesis, but supported me in the process. The completion of my Master’s

course work along with this thesis would not have been attainable without everyone. I

would like to thank my family, teachers, and friends for all your support.

First, and foremost, I would like to thank my parents. Without their love, support

and guidance I know I would not have accomplished all that I have today. I strive to be

the best because of you, and I thank that you instilled the importance of education in me

since I was a little girl. Thank you so much for believing in me and helping me attain all

my aspirations. You are the best parents and have given me the opportunity to be my

best. I love you so much!

To my fiancé, thank you for helping me make it through the long hours of

commuting, studying, and countless hours working on my coursework and thesis. You

have made my life so much easier being there and supporting me through it all. I cannot

thank you enough for keeping me level headed and the encouragement you have given

me throughout the process. There is not a day that goes by that I don’t thank you for all

that you are.

To the faculty, Dr. Roberto Quintana and Wendy Buchan, your guidance and

support throughout this thesis has been more than I can ask. In the midst of my busy life,

you have helped attain my degree and for that I will be forever grateful. I am lucky to

have found such great faculty support in this program. I cannot say thank you enough!

viii

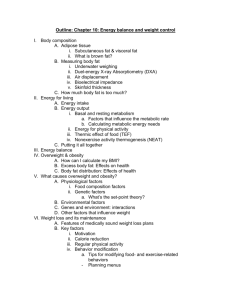

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………… viii

List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………. xii

List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………xiii

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION …………….. ………………………………….……………... 1

Statement of Purpose………………………………………………………….. 3

Significance of Thesis………………………………………………………… 3

Definition of Terms…………………………………………………………… 3

Limitations……………………………………..………………………………4

Delimitations………………………..………………………………………….5

Assumptions……………..……………………………………………………..5

Hypotheses……………….…………………………………………………….5

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE……………………………………………………... 6

Resting Energy Expenditure Methodology…………………………………… 6

Effects of Fats and Carbohydrates on Resting Energy Expenditure………….. 7

Increase in Caloric Need on a Low-Fat Diet…………….……………………11

No Increase in Caloric Need on a Low-Fat Diet….…………………………..12

Macronutrient Composition…………………….…………………..………...14

Body Composition on a Low-Fat Diet…….……………………………….…15

Summary……………………….……………………………………………..17

3. METHODOLOGY……………….………………………….………………….. .19

Subjects…………………….………………………………………………….19

Experimental Design………………………………………………………….20

Data Analysis………………………………………………………………....24

4. RESULTS……………………………………………………………………..…. 25

Resting Energy Expenditure and Respiratory Quotient…………………........25

Changes in Nutrient Intake……………………………………………………25

ix

Energy and Dietary Fat Intake………………………………..…………….25

Energy Cost of Weight Maintenance………………………..……………...26

Changes in Weight…………………………………..……………………...26

Percent Body Fat, Fat Mass, and Fat Free Mass…………………...……….27

5. DISCUSSION…………...……………………………………………………….37

Future Research………….…………..…………………………...…………40

Conclusion……………….…………………..…………………...…………41

REFERENCES………………………………………………………………..…… .42

x

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

1.

Page

Table 1. Changes in weight, percent body fat, daily energy intake, resting

energy expenditure, respiratory quotient, fat mass, and fat free mass

during eucaloric restriction of dietary fat intake……………………….28

2.

Table 2. Differences in analysis of dietary energy, fat, and carbohydrate

of the same 7 day menu cycles by Hazelton Laboratories, Nutritionist IV,

and Nutrition Data Systems…………………………………………….29

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

1.

Page

Figure 1. Effects of Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) with dietary fat

restriction………………………..……………………………………......31

2.

Figure 2. Effects of Respiratory Quotient (RQ) with dietary fat

restriction………………………………………………………….….......32

3.

Figure 3. Effects of Body Weight (BW) with dietary fat restriction. …....33

4.

Figure 4. Effects of Fat Free Mass (FFM) with dietary fat restriction..….34

5.

Figure 5. Effects of Fat Mass (FM) with dietary fat restriction…………..35

6.

Figure 6. Effects of Body Fat (BF) with dietary fat restriction………......36

xii

1

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The health benefits of adopting an isoenergetic, low-fat, high- complexcarbohydrate diet are controversial. From the patient’s perspective, an ideal treatment of

obesity would permit generous food intake and yet result in the loss of body fat without

the discomfort and inconvenience of exercise. Although pharmacologic approaches

toward increasing energy expenditure are under investigation, modifying the diet

composition to achieve the same goals has more inherent appeal. The success of

individuals who lose weight by changing from high fat diets to low-fat diets has

prompted numerous, well-controlled studies of this phenomenon. High-carbohydrate,

low-fat diets have been shown to reduce energy intake (Lissner, Levitsky, Strupp,

Kalkwarf, & Roe 1987) and confer thermogenic benefits. Not all studies have found

benefits, as measured by weight loss (Leibel, Hirsch, Appel, & Checani, 1992) or

increased energy expenditure (Abbott, Howard, Ruotolo, & Ravussin, 1990) in response

to low-fat, high-carbohydrate, isocaloric diets, however.

Prior research has suggested that low-fat, high-carbohydrate (CHO) diets

increases weight loss (Abbot et al., 1990; Astrup, Buemann, Christensen, Madsen, 1994;

Barrett-Connor, Friedlander, 1993; Cunningham, 1980). In fact, for weight loss purposes,

low-fat intake is as effective and more satisfying when compared to diets maintaining the

usual fat intake and restricting the amount of food (Astrup et al., 1994). There are two

factors that support this claim. First, CHO-rich foods have lower caloric density, and

2

therefore, a larger volume. This leads to a natural restriction of energy intake without the

discomfort of food deprivation. Secondly, High-CHO foods may be thermogenic. While

the energy cost of depositing dietary fat in the adipose tissue is minimal, dietary CHO

needs to be first converted to triglycerides for storage. The energy cost of this process is

approximately 25% of the energy obtained from CHO (Hegsted, Ausman, Johnson,

Dallal, 1993). Therefore, when the same amount of energy is as CHO, instead of fat, 25%

less energy is deposited in the adipose tissue. Between these two explanations the former

has gained a wider acceptance. Although the latter explanation has a solid biochemical

foundation, it remains controversial.

The literature regarding a thermogenic effect of low-fat, high-CHO diets reveals

conflicting evidence. Several studies have demonstrated an increase in the energy cost of

weight maintenance with low-fat diets (Barrett-Connor & Friedlander, 1993; Hegsted et

al., 1993; Leibel et al., 1992). Other studies have failed to find any change in energy

expenditure on low-fat diets (Lissner et al., 1987; Martin, Su, Jones, Lockwood,

Tritchler, Boyd, 1996). Given the biochemical basis for an increase in energy expenditure

with high-CHO, low-fat diets, further research is needed to establish the reason for such

equivocal findings.

Therefore the body of evidence indicates that there are likely benefits of a low fat

with regard ECWM, body composition, and REE. If we are able to demonstrate that low

dietary fat intake can increase the energy cost of weight maintenance, and induce

beneficial body composition changes this would clarify the efficacy of a low fat diet in a

post-menopausal female population.

3

Statement of Purpose

The present study was designed to answer the following three questions; 1) Does

dietary fat restriction increase the caloric need to maintain weight? 2) Does lowering the

fat intake in the diet affect resting energy expenditure (REE)? 3) Does dietary fat

restriction affect body composition?

Significance of Thesis

Prior research has examined the impact of resting energy expenditure and body

composition on a eucaloric diet, but few studies have assed the relationship in

postmenopausal women. Additionally, no study has examined the relationship of energy

cost of weight maintenance, resting energy expenditure, and body composition in

postmenopausal women, both obese and non obese.

Definition of Terms

Amenorrhoea: No menstruation for more than 9 months (Mosby’s Medical Dictionary).

Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA): A technique to estimate body composition

based on the difference in electrical conductive properties of various tissues.

Body Composition: The relative amount of fat-free mass and fat mass of the body.

Body Mass Index (BMI): Describes relative weight for height, and is calculated by

dividing body mass in kilograms by height in meters squared (Expert panel on the

identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight in adults, 1998).

Fat Mass (FM): A measure of the amount of lipid content of the body.

Energy Cost of Weight Maintenance (ECWM): Energy intake required to maintain body

weight and prevent weight loss.

4

Fat-Free Mass (FFM): A measure of the total body mass, including water, protein and

mineral content of the human body.

Respiratory Exchange Ration (RER): The ratio of the volume of carbon dioxide produced

to the volume of oxygen consumed in respiration over a period of time.

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE): The resting daily energy expended in a fasted state

under a neutral environment (Sims & Danforth, 1986).

Limitations

1. Fitness level (measured by VO2 max) and its effects on REE were not controlled.

2. Physical activity levels were not controlled.

3. The REE coefficient of variation using indirect calorimetry is 3.6%

4. Diet interventions were not randomized and the order effects of dietary manipulation

were not controlled.

5. The study was not blinded. Therefore, the subjects and investigators were aware of the

daily treatments.

Delimitations

1. The impact of family influence was not monitored.

2. Subjects were limited to the Sacramento area.

3. Subjects were limited to females.

4. Subjects were limited to postmenopausal women between the ages of 43 & 81.

5. ECWM values were adjusted monthly prior to the beginning of each dietary

intervention period.

5

Assumptions

1. Subjects adhered to the pretest instructions prior to laboratory testing.

2. Each subjects’ REE test reflected their true REE.

3. Participants were honest about self-reported activity levels.

4. Subjects’ weight gain or loss is due to changes in an energy source from carbohydrate,

fat, or protein.

Hypotheses

1. Total caloric need (ECWM) will not change in response to a reduced dietary lipid

composition of an eucaloric diet.

2. A reduction in dietary lipid composition of an eucaloric diet will not alter body

composition.

3. A reduction in dietary lipid composition of an eucaloric diet will not alter REE

6

CHAPTER 2

Review of Literature

The prevalence of obesity in the adult population in American society has reached

epidemic proportions (World Health Organization, 1998). As a result of the obesity

epidemic, researchers around the world have begun to look at the effect of resting energy

expenditure and body composition. REE comprises 75% of our daily energy expenditure,

therefore researchers are looking to individuals to see a relationship between obesity and

lower resting metabolic rates, in hopes of prescribing a low-fat diet to induce weight loss

and a decrease in body composition. This chapter provides a description of resting energy

expenditure and reviews the effects of energy cost of weight maintenance and body

composition on a low-fat diet.

Resting Energy Expenditure Methodology

Resting energy expenditure (REE) is the number of calories utilized at rest and

makes up two-thirds of all the energy expended in one day. The term REE is commonly

used interchangeably with resting metabolic rate (RMR) and basal metabolic rate (BMR).

Resting energy expenditure represents the largest percentage of an individual’s daily

energy expenditure which is why many researchers have been interested in REE adaptive

responses to different dietary and physical activity interventions.

A reduction in body weight can be achieved by decreasing caloric intake or to

increase physical activity expenditure to induce a negative caloric deficit (Hill, 2006).

With dietary restriction, an appropriate and accurate caloric deficit must be calculated for

7

a successful weight loss program. This can be done with knowledge of an individual’s

REE. An accurate method to measure REE is utilizing indirect calorimetry (Compher,

Frankenfield, Keim, Roth-Yousey, 2006).

Effects of Fats and Carbohydrates on Resting Energy Expenditure

Brehm, Seeley, Daniels, D’Alessio (2003) designed a randomized, controlled trial

to determine the effects of a very low carbohydrate diet on body composition and

cardiovascular risk factors. Subjects were randomized to 6 months of either an ad

libitum very low carbohydrate diet or a calorie-restricted diet with 30% of the calories as

fat. Anthropometric and metabolic measures were assessed at baseline, 3 months, and 6

months. Fifty-three healthy, obese female volunteers (mean body mass index, 33.6 ± 0.3

kg/m2) were randomized; 42 (79%) completed the trial. Women on both diets reduced

calorie consumption by comparable amounts at 3 and 6 months. The very low

carbohydrate diet group lost more weight (8.5 ± 1.0 vs. 3.9 ± 1.0 kg; P < 0.001) and more

body fat (4.8 ± 0.67 vs. 2.0 ± 0.75 kg; P < 0.01) than the low fat diet group. Mean levels

of blood pressure, lipids, fasting glucose, and insulin were within normal ranges in both

groups at baseline. Although all of these parameters improved over the course of the

study, there were no differences observed between the two diet groups at 3 or 6 months.

Based on these data, a very low carbohydrate diet is more effective than a low fat diet for

short-term weight loss and may increase resting energy expenditure (Brehm, et al. 2003).

The energy to metabolize fats and carbohydrates may affect weight loss in this ad libitum

carbohydrate group and caloric restricted fat group. The possibility that differences in the

8

macronutrient composition of the diet alter energy expenditure bears further

investigation.

Volek, Sharman, Gómez, Judelson, Rubin, et al. (2004) looked to compare the

effects of isocaloric, energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate ketogenic (VLCK) and

low-fat (LF) diets on weight loss, body composition, trunk fat mass, and resting energy

expenditure (REE) in overweight/obese men and women. 15 healthy, overweight/obese

men and 13 premenopausal women were prescribed two energy-restricted (-500 kcal/day)

diets: a VLCK diet with a goal to decrease carbohydrate levels below 10% of energy and

induce ketosis and a LF diet with a goal similar to national recommendations

(%carbohydrate:fat:protein = ~60:25:15%). The authors discovered that dietary energy

was restricted, but was slightly higher during the VLCK (1855 kcal/day) compared to the

LF (1562 kcal/day) diet for men. Both between and within group comparisons revealed a

distinct advantage of a VLCK over a LF diet for weight loss, total fat loss, and trunk fat

loss for men (despite significantly greater energy intake). The majority of women also

responded more favorably to the VLCK diet, especially in terms of trunk fat loss. The

greater reduction in trunk fat was not merely due to the greater total fat loss, because the

ratio of trunk fat/total fat was also significantly reduced during the VLCK diet in men

and women. Absolute REE (kcal/day) was decreased with both diets as expected, but

REE expressed relative to body mass (kcal/kg), was better maintained on the VLCK diet

for men only. Individual responses clearly show the majority of men and women

experience greater weight and fat loss on a VLCK than a LF diet. This study shows a

clear benefit of a VLCK over LF diet for short-term body weight and fat loss, especially

9

in men. A preferential loss of fat in the trunk region with a VLCK diet is novel and

potentially clinically significant but requires further validation. These data provide

additional support for the concept of metabolic advantage with diets representing

extremes in macronutrient distribution (Volek et al. 2004).

Brehm, Spang, Lattin, Seeley, Daniels et al. (2005) reported that obese women

randomized to a low-carbohydrate diet lost more than twice as much weight as those

following a low-fat diet over 6 months. The difference in weight loss was not explained

by differences in energy intake because women on the two diets reported similar daily

energy consumption. They hypothesized that chronic ingestion of a low-carbohydrate diet

increases energy expenditure relative to a low-fat diet and that this accounts for the

differential weight loss. Fifty healthy, moderately obese (body mass index, 33.2 ± 0.28

kg/m2) women were randomized to 4 months of an ad libitum low-carbohydrate diet or an

energy-restricted, low-fat diet. Resting energy expenditure (REE) was measured by

indirect calorimetry at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Physical activity was estimated

by pedometers. The thermic effect of food (TEF) in response to low-fat and lowcarbohydrate breakfasts was assessed over 5 h in a subset of subjects. The lowcarbohydrate group lost more weight (9.79 ± 0.71 vs. 6.14 ± 0.91 kg; P < 0.05) and more

body fat (6.20 ± 0.67 vs. 3.23 ± 0.67 kg; P < 0.05) than the low-fat group. There were no

differences in energy intake between the diet groups as reported on 3-day food records at

the conclusion of the study (1422 ± 73 vs. 1530 ± 102 kcal; 5954 ± 306 vs. 6406 ± 427

kJ). Mean REE in the two groups was comparable at baseline, decreased with weight

loss, and did not differ at 2 or 4 months. The low-fat meal caused a greater 5-h increase in

10

TEF than did the low-carbohydrate meal (53 ± 9 vs. 31 ± 5 kcal; 222 ± 38 vs. 130 ± 21

kJ; P = 0.017). These results confirm that short-term weight loss is greater in obese

women on a low-carbohydrate diet than in those on a low-fat diet even when reported

food intake is similar. The differential weight loss is not explained by differences in REE,

TEF, or physical activity and likely reflects underreporting of food consumption by the

low-fat dieters (Brehm, et al. 2005).

Abbot et al., (1990) studied the effects of fat and carbohydrate on resting energy

expenditure. They determined a high-dietary fat intake may be an important

environmental factor leading to obesity in some people. The mechanism could be either a

decrease in energy expenditure and/or an increase in caloric intake. To determine the

relative importance of these mechanisms they measured 24-h energy expenditure in a

whole body calorimeter in 14 nondiabetic subjects and in six subjects with non-insulindependent diabetes mellitus, eating isocaloric, weight-maintenance, high-fat, and highcarbohydrate diets. In nondiabetics, the mean total 24-h energy expenditure was similar

(2,436 +/- 103 vs. 2,359 +/- 82 kcal/day) on high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets,

respectively. The means for sleeping and resting metabolic rates, thermic effect of food,

and spontaneous physical activity were unchanged. Similar results were obtained in the

diabetic subjects. In summary, using a whole body calorimeter, researchers found no

evidence of a decrease in 24 hour energy expenditure on a high-fat diet compared with a

high-carbohydrate diet.

11

Increase in Caloric Need on a Low-Fat Diet

A review by Bray and Popkin, 1998, found 28 intervention studies where subjects

were asked to reduce dietary fat without energy restriction. There was an average weight

loss of 1.6 g/day for each 1% reduction in dietary fat. The meta-analysis reports an

unpublished study by Astrup, indicating that in 15 of 16 identified studies, reducing

dietary fat led to a greater, yet modest decrease in body weight (2.5 kg, 95% confidence

interval 5 1.5–3.5 kg, P , 0.0001) compared with the control groups. There were

significant positive correlations between the reduction in dietary fat and amount of

weight loss (r = 0.37) and between initial body weight and weight loss (r = 0.52) (Bray &

Popkin, 1998). These results could be explained by the mechanism of a higher metabolic

cost to convert carbohydrate to lipid stores. Carbohydrates are more thermogenetic. The

energy cost to deposit dietary fat into adipose tissue is minimal, whereas dietary

carbohydrates must first be first converted to triglycerides for storage. This energy cost

may be the reason weight loss is observed on a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet.

Horton, Drougas, Brachey, et al. (1995) overfed lean and obese men 50% of their

energy requirement either as CHO or fat. When the excess energy was provided as CHOcalories, CHO-oxidation and energy expenditure increased, with a net of 75-85% of the

excess energy used for storage. Fat overfeeding did not stimulate either fuel oxidation or

energy expenditure, resulting in the storage of 90-95% of the excess energy. Astrup et al.

(1994) demonstrated that when isocaloric diets containing 20%-fat verses 50%-fat are

administered, each for 3 days, there was a 4% increase in daytime energy expenditure on

the low-fat diet (8,090 kJ/d to 8,401 kJ/d) and an +11 g/day fat deposition. On the high-

12

fat diet day time energy expenditure did not change (8,034 verses 8,086 kJ/d) and the fat

deposition was larger (+19.6 gm/d). Interestingly these changes were observed only in

post-obese women, but not in the never-obese controls. There might be a change in

metabolism in obese verse non obese subjects, but this bears further investigation.

No Increase in Caloric Need on a Low-Fat Diet

With some studies supporting an increase in ECWM on low-fat diets, there are

also several reports of no change. Roust, Hammel, & Jensen (1994) did not show any

change in body composition, overnight energy expenditure, REE or fat oxidation between

the 42%-fat (to stabilize weight) and 27%-fat diets in a 4 week intervention. This brief

dietary intervention could confound their interpretation. This study also did not use a

very low-fat diet, although the change was large. In addition, only the overnight REE, but

not the 24-hour total energy expenditure, were measured. Hill, Sparling, Shields, &

Heller, (1987) compared the effects of 60% CHO verses 60%-fat diets for 7 days each

and found that while there was no change in the energy expenditure, there was a change

in the nutrient oxidation, which reflected the dietary composition. Lean & James (1988)

investigated lean, obese and post-obese women on high CHO (3% fat and 45 % CHO)

versus low CHO (40% fat and 12% CHO) diets and found no significant difference in

total 24 hour energy expenditure between the diets or groups but a significantly higher

thermal effect of food on the high carbohydrate versus the low carbohydrate diet (5.8%

vs. 3.5%, respectively). Abbott et al. (1990) also found no difference in 24 hour energy

expenditures in 14 Pima Indians on a 20% versus 44% fat diet (2,436 + 103 vs. 2,359 +

82); however, an increase in the 24 hour RQ was noted with the shift from dietary fat to

13

dietary CHO. Again Abbott had a small number of subjects which may have limited the

statistical power to report a significant increase in the ECWM. Stubbs, William, Coward,

& Prentice (1995) demonstrated that when diets containing 20%, 40% and 60% fat were

compared, there was a direct relationship between the fat and energy intakes. While there

was no change in measured energy expenditure, 20%-fat and 40%-fat diets caused weight

loss, relative to the 60%-fat diet. Since weight loss leads to a lower lean body mass, this

may lower resting energy expenditure and limit weight loss reported. While these studies

did not show an increase in the ECWM on low-fat diets, this inconsistency in results may

be explained by differences in study design. Some differences in study designs included

different dietary composition, liquid diets versus solid foods (both amounts and types of

fats & carbohydrates used), different endpoints measured, small number of subjects in

some studies, and different subject composition (different ages, body compositions and

background diets).

Prewitt, Schmeisser, Bowen, Aye, Dolecek, Langenberg, Cole & Brace (1991)

showed that when 18 women were switched from a 37%-fat diet to a 20%-fat diet for 20

weeks, ECWM increased by 19% (7515 + 140 vs 9083 + 373 kJ/day) and these women

lost 2.8% body weight despite efforts to maintain weight. Leibel et al., (1995)

investigated diets rich in fat that may promote greater deposition of adipose-tissue

triglycerides than do isoenergetic diets with less fat. This possibility was examined by a

retrospective analysis of the energy needs of 16 human subjects (13 adults, 3 children)

fed liquid diets of precisely known composition with widely varied fat content, for 15-56

d (33 +/- 2 d, mean +/- SE). Subjects lived in a metabolic ward and received fluid

14

formulas with different fat and carbohydrate content, physical activity was kept constant,

and precise data were available on energy intake and daily body weight. Isoenergetic

formulas contained various percentages of carbohydrate as cerelose (low, 15%;

intermediate, 40% or 45%; high, 75%, 80%, or 85%), a constant 15% of energy as

protein (as milk protein), and the balance of energy as fat (as corn oil). Even with

extreme changes in the fat- carbohydrate ratio (fat energy varied from 0% to 70% of total

intake), there was no detectable evidence of significant variation in energy need as a

function of percentage fat intake.

Macronutrient Composition

Sacks, Bray, Carey, Smith, Ryan et al. (2009) randomly assigned 811 overweight

adults to one of four diets; the targeted percentages of energy derived from fat, protein,

and carbohydrates in the four diets were 20, 15, and 65%; 20, 25, and 55%; 40, 15, and

45%; and 40, 25, and 35%. The participants were offered group and individual

instructional sessions for 2 years. The primary outcome was the change in body weight

after 2 years in two-by-two factorial comparisons of low fat versus high fat and average

protein versus high protein and in the comparison of highest and lowest carbohydrate

content. The authors concluded that a reduced-calorie diet results in clinically meaningful

weight loss regardless of which macronutrients they emphasize (Sacks, et al. 2009).

Body Composition on a Low-Fat Diet

The idea of body weight regulation implies that a biological mechanism exerts

control over energy expenditure and food intake. This is a central tenet of energy

homeostasis. However, the source and identity of the controlling mechanism have not

15

been identified, although it is often presumed to be due to gastro-intestinal adipose

endocrine signaling areas of the brain governing appetite, satiety, and energy homestasis.

In a recent study, Blundell, Caudwell, Gibbons, Hopkins, Naslund, King, and Finlayson

(2011), using a comprehensive experimental platform, investigated the relationship

between biological and behavioral variables in two separate studies over a 12-week

intervention period in obese adults. All variables have been measured objectively and

with a similar degree of scientific control and precision, including anthropometric

factors, body composition, REE and accumulative energy consumed at individual meals

across the whole day. Results showed that meal size and daily energy intake (EI) were

significantly correlated with fat-free mass (FFM, P values < 0·02-0·05) but not

with fat mass (FM) or BMI (P values 0·11-0·45) (study 1, n=58). In study 2 (n=34), FFM

(but not FM or BMI) predicted meal size and daily EI under two distinct dietary

conditions (high-fat and low-fat). These data appear to indicate that, under these

circumstances, some signal associated with lean mass (but not FM) is related to selfselected food consumption. This signal may be postulated to interact with a separate class

of signals generated by FM. This finding may have implications for investigations of the

molecular control of food intake and body weight and for the management of obesity

(Blundell, et al 2011).

In a study by Noakes, Keogh, Foster, and Clifton (2005), researchers wanted to

evaluate the effects of a diet with a high ratio of protein to carbohydrate during weight

loss on body composition in overweight women. The subjects were randomly assigned to

1 of 2 isocaloric 5600-kJ dietary deficit interventions for 12 wk according to a parallel

16

design: a high-protein (HP) or a high-carbohydrate (HC) diet. One hundred women with a

mean (±SD) body mass index (in kg/m2) of 32 ± 6 and age of 49 ± 9 y completed the

study. Weight loss was 7.3 ± 0.3 kg with both diets. Subjects with high serum

triacylglycerol (>1.5 mmol/L) lost more fat mass with the HP than with the HC diet (

± SEM: 6.4 ± 0.7 and 3.4 ± 0.7 kg, respectively; P = 0.035). They concluded that an

energy-restricted, high-protein, low-fat diet provides nutritional and metabolic benefits

that are equal to and sometimes greater than those observed with a high-carbohydrate

diet. It is important to note that a limitation of this study is that a HP diet is the least

efficient macronutrient. These diets induced more weight loss initially due to fluid loss

but the body adjusts by retaining more body water and hence higher FFM.

Summary

In summary, the literature suggesting that low-fat, high-carbohydrate (CHO) diets

promoting weight loss are supported by the thermogenic effect of low-fat, high-CHO

diets. In fact, for weight loss purposes low-fat intake is as effective and more satisfying

when compared to diets maintaining the usual fat intake and restricting the amount of

food. While the energy cost of depositing dietary fat in the adipose tissue is minimal,

dietary CHO needs to be first converted to triglycerides for storage. The energy cost of

this process is approximately 25% of the energy obtained from CHO (Hegsted et al.,

1993). Therefore, when the same amount of energy is as CHO, instead of fat, 25% less

energy is deposited in the adipose tissue. In most studies reviewed, macronutrient

composition had no effect on REE. When body composition was effected, it was noticed

in the obese population. This might indicate that changes in metabolism are occurring in

17

an obese verses non obese population. Given the biochemical basis for an increase in

energy expenditure with high-CHO, low-fat diets, further research is needed to establish

the reason for such controversy in the literature.

18

CHAPTER 3

Methodology

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of dietary fat restriction on

the energy intake required to maintain body weight, and weight loss (ECWM). The study

also investigated resting energy expenditure (REE), and body composition, including

FM, FFM, and BF, in post menopausal women.

Subjects

Sixty-four healthy post menopausal women were recruited to the study after

signing the informed consents approved by the Institutional Human Investigation

Committee of the University of California, Davis. All participants were examined by the

principal investigator and chemistry-20 panels were obtained during fasting. Individuals

with diabetes mellitus, liver or kidney disease, or who had plasma triglyceride above 2.82

mM/L or LDL-cholesterol above 4.26 mM/L were excluded. Menopause was defined by

at least 9 months history of amenorrhea or surgical removal of both ovaries. Only women

who were menopausal or taking continuous hormone replacement therapy were included.

Women on cyclical hormone replacement were excluded. Twenty-four women used

hormone replacement; 14 estrogen only, and 10 combination of estrogen and

progesterone. The dose of the hormones and all the other medications or supplements

remained unchanged throughout the study. The physical activity levels were maintained

and monitored by activity questionnaires. Four women were excluded from the study

during the controlled feeding phase due to non-compliance. Eight women failed to

19

complete the four month protocol. The remaining 56 (age = 58.4 ± 7.7 years, Mean+S.D.)

completed the entire study. Upon re-evaluation of the study, complete data was obtained

from 38 subjects (age = 59.2 ± 9.1, Mean+S.D.).

Experimental Design

Four cohorts of 16 participants were enrolled every 4 months. Each cohort went

under 3 dietary interventions over a 4 month period. Dietary interventions were

administered in a sequential order. Pre and post testing were administered at the

beginning and end of each dietary intervention.

Dietary Intervention

Dietary intervention involved a 4-month long eucaloric controlled-feeding which

provided all the food. The study was designed to reduce the fat intake stepwise to 15% of

the daily energy intake. Participants’ diet prior to the study was defined as “the habitual

diet.” The habitual diet was determined by having participants keep a 7 day food diary,

which was reviewed with a dietitian. For the eucaloric controlled-feeding, participants ate

their dinners, 5 days a week at the study site, and received their breakfasts, lunches,

snacks and weekend meals in pre-packaged form as take-outs. The food was prepared in

7-day menu cycles in the study kitchen. The ingredients were weighed to the nearest

gram. The trays were inspected to assure complete consumption of the food. Participants

were required to return any unconsumed food and record any foods eaten not provided by

the study. They were to call the study coordinator immediately if any food was lost or

missing which would be replaced. After entering the study participants consumed a 35%fat diet during the first four weeks. The goal was to bring all the participants to the same

20

fat intake level and adjust the energy intake to maintain weight as a preparation to low-fat

diet phases. During this period, the initial energy intake was individualized based on each

subject’s resting energy expenditure (measured by indirect calorimetry) and multiplied by

a factor based on their physical activity level (estimated by physical activity

questionnaire). The physical activity questionnaire was a sheet of paper that asked

subjects to document their physical activity each week. Subjects were weighed 5 times

each week and the energy content of the diet was adjusted when weight varied by more

than 1 kg, from the entry level, in order to maintain the initial body weight. After

stabilizing the weight and energy intake during the 35%-fat period, participants were

switched to a diet containing 25%-fat for six weeks, and then 15%-fat for another six

weeks. Participants kept daily records of any additional dietary intake of uneaten foods.

Non-compliance was defined as more than 1% of calories altered from the experimental

diet on more than one occasion. Alcohol was not included in the diet. One alcoholic drink

per week was permitted as long as the intake was recorded in the food diary. The

majority of women did not consume any alcohol. Food from an entire week during each

diet period was homogenized and sent to the Hazelton Laboratory (Madison, WI) for

analysis. Actual fat contents of the diets were reported as 31%, 23% and 14%, and

carbohydrate contents as 53%, 60%, and 67%, respectively. This was compared to

analysis of the 7-day diet cycles analyzed by a registered dietitian on both Nutrition Data

System (NDS 93, University of Minnesota) and Nutritionist IV.

21

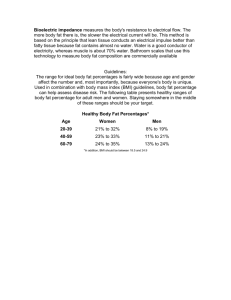

Body composition

Bioelectrical impedance (BIA) was used to assess body composition and provide

values for FFM and FM. BIA is a simple, inexpensive, and noninvasive method of

measuring body composition (Gallagher & Song, 2003; Segal, Van Loan, Gitzgeral,

Hodgdon & Van Itallie, 1988). BIA assessed body composition in the past absorptive

state by passing 800 μA alternating current at 50 kHz from the right hand to the

ipsilateral foot while the subject remained supine (Biostat 1500, British Isles,

BioAnalogics-HMS1000, Beaverton, OR). Sigal et al. (1998) found that the estimation of

FFM by BIA was reliable, and the precision of the measurement increased when

population specific equations were used. Heyward & Wagner (2004) suggest the use of

the following equations published by Segal et al. (1988): FFM [FFM = 0.00091186 x

height2 (cm2) – 0.001466(impedance) + 0.2999 x body weight (kg) – 0.07012 x age

(years) + 9.37938], FM [FM = weight (kg) – FFM], and percent body fat [percent body

fat = FM (kg)/weight (kg) x 100]. The multiple correlation coefficient between

densitometrically determined FFM which predicted by BIA is 0.93 and the standard error

of estimate (SEE) was 1.95 kg for FFM (Chapman, Bannerman, Cowen, & Maclennan,

1998). The correlation between densitometrically determined percent body fat and

predicted percent body fat was 0.91 and the SEE was 3.18% (Segal et al., 1988).

22

Physical Activity

For the duration of the study, exercise activity was kept constant and monitored

by a physical activity questionnaire that asked subjects to document the physical activity

they participated in daily. At baseline and during the 8 months of the study, each subject

kept a daily diary of activity type, duration, intensity, and frequency. The study

coordinator (a registered dietitian and exercise physiologist) reviewed these diaries

monthly. If there was any deviation from initial activity levels, the study coordinator

counseled the subject to resume her normal activity, which was fully accomplished.

Deviations in activity during the study primarily resulted from illness or changes in the

weather, which did not last for prolonged periods of time before the women resumed

their previous activity level (1 week). During the course of the study, there were no

significant changes in exercise activity.

Assessment of Resting Energy Expenditure and Respiratory Quotient

The subjects were asked to arrive in lightweight, indoor clothing. Light blankets

were made available to those that requested them. Prior to testing, subjects rested for 30

minutes while lying on a treatment table in a thermoneutral environment that was quiet

and dimly lit. During this time, subjects refrained from listening to music, watching

television, readying, or other activities.

REE was measured in the fasting state, before breakfast, after 30 minutes of rest.

REE was collected for 10 minutes by continuous indirect calorimetry with a ventilated

hood system (Applied Electrochemistry/Thermox, Pittsburgh, PA). The gas analyzer was

calibrated before each procedure with a calibration gas of 16% O2, 4% CO2, and balance

23

N2. The pneumotach was calibrated and VO2 and VCO2 were measured each minute. As

suggested by Compher el al. (2006), the initial five minutes were discarded. Five minutes

of steady state were averaged and used to derive REE. Steady state was defined as a

period of five consecutive minutes during which the coefficient of variation (CV) for

VO2 and VCO2 were < 10% (Compher et al., 2006). The VO2 and VCO2 during the

steady state with the lowest CV were then used to calculate REE with the Weir equation

(Weir, 1949). The Weir equation is as follows: REE (kcal/min) = [(1.1(VCO2/VO2)]+3.9)

x VO2] (Weir, 1949).

Data Analysis

Data were expressed as means + standard deviations (SD). The dependent

variables REE, RER, and body composition values were analyzed with respect to dietary

intervention by analysis of variance with repeated measures. Significant main effects or

interactions were analyzed by Tukey’s Post-hoc test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. All the analyses were carried out using Statistica 5.5 for windows

(StatSoft Inc, Tulsa, OK).

24

CHAPTER 4

Results

Resting Energy Expenditure and Respiratory Quotient

The primary question of this study was if there was an effect of dietary fat intake

on resting energy expenditure during a eucaloric intervention. REE did not significantly

change with respect to dietary intervention (p=.979) (Figure 1). There was a trend for

respiratory exchange ratio to increase with a reduction in lipid composition of the

eucaloric diets (p=.067) (Figure 2).

Changes in Nutrient Intake

Although the controlled-feeding phase was designed by calculated, computer

generated analysis to deliver 35%, 25% and 15% of the energy intakes from fat,

laboratory and chemical analysis of the diet showed that the actual dietary fat intakes

were 31%, 23% and 14% respectively. The corresponding carbohydrate intakes were

53%, 60%, and 67% of the daily energy (Table 2).

Energy and Dietary Fat Intake

At the entry, the self-reported energy intake was 6896+ 1726 kJ, while at the end

of the 31%-fat period the energy intake required for weight maintenance was 8724 +

1281 kJ, or 116+16 kJ per kg. The difference between the actual and self reported energy

intakes represented an under-reporting of 1828+445 kJ/day. The magnitude of underreporting correlated weakly with the degree of obesity (r = 0.309, p < 0.04).

25

Body weight correlated strongly with ECWM (r = 0.77, p < 0.0001). The initial

self reported dietary fat intake had a stronger relationship with the body weight (r =

0.321, p < 0.01) than with the poor relationship it had with self reported energy intake (r

= 0.263, p < 0.05). In addition, when compared with lean women, obese women

consumed higher amounts of fat (36.6+6.6% vs 29.4+6.7%, p < 0.0005). Taken all

together, these findings suggested that self-reported food records are more useful in the

assessment of dietary fat intake than the energy intake.

Energy Cost of Weight Maintenance

During the eucaloric feeding as dietary fat decreased from 31 % to 23% to 14 %,

the energy cost of weight maintenance increased from 8724+1281 kJ, to 8946+ 1310 kJ,

and to 9122+ 1365 kJ, respectively. These increases were significant ( +223+400 kJ, p <

0.02 and +398+638 kJ, p < 0.0001 ). At the end of the metabolic feeding phase 29

women required an increase in the energy intake ( +770+592 kJ), and 20 women did not

(-154+269 kJ). All the obese subjects belonged to the first group (+895+528 kJ).

Changes in Weight

During the eucaloric phase, weight and body composition slightly (~% approx.)

decreased with each feeding. There was a significant difference in body weight between

baseline and after the 35% fat diet (p=0.0003), no significant change between the 35%

and 25% fat diet (p=0.218), and no significant change between the 25% fat diet and the

15% fat diet (p=0.156) (Figure 3).

26

Percent Body Fat, Fat Mass, and Fat Free Mass

There was a significant reduction in body fat, fat mass, and fat free mass after the

35% fat eucaloric feeding (p=0.033, 0.0008, 0.0001) respectively. There was no

significant difference between the 25% fat (p=0.297, 0.224, 0.419) and 15% fat feeding

(p=0.079, 0.147, 0.177) (Figure 4, 5, 6).

27

Table 1.

Changes in weight, percent body fat, daily energy intake, resting energy expenditure,

respiratory quotient, fat mass and fat free mass during eucaloric restriction of dietary fat

intake (Mean + S.D., n = 38).

WEIGHT (kg)

BODY FAT

ENERGY INTAKE

35%-FAT

25%-FAT

15%-FAT

78.9+22.8*

78.6+22.7

78.4+23.0*

30.3+9.4

30.1+9.4

29.8+9.7

8724+1281

8946+1310*

9122+1365*

1414.7+283.9

1426.7+328.8

1423.7+299.6

(kJ/day)

REE (kcal)

RER

0.82+0.09

0.83+0.07

0.84+0.07

FAT MASS

25.8+15.0*

25.5+15.0

25.3+15.2*

FAT FREE MASS

53.1+8.3*

53.0+8.4

53.0+8.4*

Note. (*) indicates significantly different between groups, P<0.05.

Table 2.

28

Differences in analysis of dietary energy, fat, and carbohydrate of the same 7 day menu

cycles by Hazelton Laboratories, Nutritionist IV, and Nutrition Data Systems.

35% Fat Menu

Hazelton

Energy

Fat

Carbohydrate

Protein

Cholesterol

Fiber

(kJ)

(gm)

(gm)

(gm)

(mg)

(gm)

1571

52.9

205.7

68.6

161

14.3

1665

63.7

208.9

68.2

202

13.8

1748

67.9

205.6

78.7

322

12.1

Energy

Fat

Carbohydrate

Protein

Cholesterol

Fiber

(kJ)

(gm)

(gm)

(gm)

(mg)

(gm)

1500

38.6

224.3

65.7

134

17.2

1603

45.2

238.7

68.1

157

17.7

1747

44.2

263.9

79.2

166

12.4

Laboratories

Nutrition Data

Systems

Nutritionist IV

Hazelton

Laboratories

Nutrition Data

Systems

Nutritionist IV

29

Hazelton

Energy

Fat

Carbohydrate

Protein

Cholesterol

Fiber

(kJ)

(gm)

(gm)

(gm)

(mg)

(gm)

1629

25.7

272.9

77.1

120

17.1

1607

27.1

274.9

73.9

138

19.1

1749

31.4

286.4

86.7

286

12.6

Laboratories

Nutrition Data

Systems

Nutritionist IV

30

1600

*

1550

*

Resting Energy Expenditure (kcal)

*

1500

1450

1400

1350

1300

1250

Baseline

35% Fat

25% Fat

15% Fat

Dietary Intervention

Figure 1. Effects of Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) with dietary fat restriction. (*)

indicates not significantly different from baseline , P>0.05.

31

0.88

*

0.87

0.86

*

*

Respiratory Quotient (RQ)

0.85

0.84

0.83

0.82

0.81

0.80

0.79

0.78

Baseline

35% Fat

25% Fat

15% Fat

Dietary Intervention

Figure 2. Effects of Respiratory Exchange Ratio (RER) with dietary fat restriction.

(*) Indicates trend, P=0.06.

32

90

88

*

*

*

86

84

Body Weight (kg)

82

80

78

76

74

72

70

68

Baseline

35% Fat

25% Fat

15% Fat

Dietary Intervention

Figure 3. Effects of Body Weight (BW) with dietary fat restriction. (*) indicates

significantly different from baseline, P<0.05.

33

57

*

*

*

56

Fat Free Mass (%)

55

54

53

52

51

50

49

Baseline

35% Fat

25% Fat

15% Fat

Dietary Intervention

Figure 4. Effects of Fat Free Mass (FFM) with dietary fat restriction. (*) indicates

significantly different from baseline, P<0.05.

34

34

32

*

*

*

30

Fat Mass (%)

28

26

24

22

20

18

Baseline

35% Fat

25% Fat

15% Fat

Dietary Intervention

Figure 5. Effects of Fat Mass (FM) with dietary fat restriction. (*) indicates significantly

different from baseline , P<0.05.

35

0.35

0.34

*

*

*

0.33

Body Fat (%)

0.32

0.31

0.30

0.29

0.28

0.27

0.26

0.25

Baseline

35% Fat

25% Fat

15% Fat

Dietary Intervention

Figure 6. Effects of Body Fat (BF) with dietary fat restriction. (*) indicates significantly

different from baseline , P<0.05.

36

CHAPTER 5

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the effects of dietary fat intake while

controlling ECWM and to investigate the effects of dietary fat restriction among postmenopausal women. Our results demonstrate that a restriction in fat intake increases the

ECWM. Dietary fat restriction has no effect on REE or RER, and decreases were found

in FM, FFM, and BF despite a large significant increase in ECWM calories.

We observed that as dietary fat intake decreased from 31% to 23% and to 14%,

the daily energy requirement increased by 223+400 kJ and 398+638 kJ. At the end of the

31%-fat diet daily energy requirement was 8724 kJ, providing 2706 kJ from fat. When

the fat intake was reduced to 23% and 14% respectively, relative contribution of fat

calories decreased to 2007 kJ and 1221 kJ per day. When compared to the 23%-fat and

14%-fat diets, 31%-fat diet provided 698 kJ and 1483 kJ more energy from fat. These

findings are supported by previous research that found carbohydrates that are used to

synthesize lipid are 25% less efficient (Hegsted et al., 1993). One could speculate that a

person could consume 25% more calories in CHO than fat without gaining weight. If

these differences in fat-calories can be replaced with an equivalent amount of CHO

calories, the increases in energy requirement would be 233 kJ/day during the 23%-fat,

and 494 kJ/day during the 14%-fat diets. These predicted values were similar to the

actual increases in caloric intake seen in our study. Another antidotal observation is that

all the women who required an increase in caloric intake to maintain ECWM were obese.

37

This could suggest that obese may process macronutrients differently than normal weight

post-menopausal women.

Our study clearly demonstrated an increase in the ECWM in proportion to the

amount of fat reduction and increase in CHO. While our study failed to demonstrate any

change in REE, this suggests that the increase in energy expenditure must occur during

the day and likely post-prandially. Further controlled research looking at 24-hour energy

expenditures with post-prandial values compared, more variations in fat intake, with

whole foods and a variety of genetic backgrounds need to be done to fully explain the

inconsistencies seen in this area. Brehm et al., (2003) did not find any differences in

REE when comparing a high fat to high carbohydrate diet. They concluded that the

macronutrient makeup of a diet does not affect REE. However, we feel there is sufficient

evidence to support both an increase in the ECWM and when consumed ad-libitum a

decreased caloric intake due to the lower nutrient density with very low-fat diets leading

to the weight loss associated with low-fat diets.

Previous studies have suggested the importance of RER adjusting for the

oxidative rates in metabolism (Rising, Tataranni, Snitker, Ravussin, 1996). Although

there was not a significant change in RER (p=.067), we observed a trend. After the first

eucaloric feeding, RER dropped to correlate with the amount of fat in the diet. As we

decrease the amount of fat, RER increased to match the fat oxidative rates. This trend

was expected to show the body’s adjustment to the amount of fat and carbohydrate being

oxidized. This supports that low fat diets require more energy to maintain body weight.

38

This is important because if we utilize less fat and our metabolic rates decrease with age,

it can contribute to an increase in obesity (Rising et al., 1996).

While we tried to maintain body weight and control for body composition using a

eucaloric diet, decreases in FFM, FM, and BF were observed. FFM decreased from

baseline to the end of the 15% fat intervention by 0.6% which was significant (p=.001).

FM similarly decreased by 1.3% along with a decrease of 0.8% in BF. This demonstrates

that by decreasing the proportion of fat to carbohydrate macronutrients it allows subjects

to eat more and still lose weight. While we increased the intake of calories to prevent

further weight loss to maintain body weight, the decrease in body composition was

significant. Therefore, there must be a mechanism to explain the change in weight. Our

first prediction is that we did not account for the efficiency of macronutrients in the diet.

It is more costly for the body to process carbohydrates. This energy difference equates to

about 25% of carbohydrates consumed that must be broken down and metabolized in

order to be stored as lipid in the body. This increase cost of metabolizing carbohydrates

may represent the amount of weight loss that occurred in our study. There could have

also been an error in calculating the eucaloric diet, or an error in calculating the

additional calories needed to maintain body weight, or physical activity might not have

been monitored accurately. All of these factors could lead to an error in maintaining body

composition.

Future Research

There are some areas of our study that could be improved. Our study was very

well controlled for diet by sending our food samples to Hazelton Laboratory to be

39

analyzed. The most important implication for future studies is to look at post prandial

values. We collected resting energy expenditure after 12 hours fasting. With the results of

our study indicating that there is not a significant change in REE, differences could be

occurring during the day post prandially. Also, it is important to note that by maintaining

a eucaloric diet, we did not control for how the calories are being processed

metabolically. This could explain the predicted mechanisms of the weight loss that

occurred in our study. Additionally physical activity levels could have been monitored

directly than by a recall survey questionnaire. While we obtained physical activity logs

from the subjects to account for the calories being burned, directly monitored physical

activity would be more accurate . We could also improve our body composition data

collection. In this study we used BIA to calculate body composition. The new gold

standard is the DEXA (Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry). While it is extensively used

for the assessment of body composition and is considered valid and reliable, it is large

and expensive. Another area our study could improve is the length of the study. The first

dietary intervention was 4-weeks, the second was 6-weeks, and the last dietary

intervention was 6-weeks. Although this may be sufficient time, additional long term

studies might yield different results.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study supports that low-fat intake increases the ECWM,

causes less efficient storage of energy, and decreases in body weight. However, there are

other benefits of low fat caloric diet. High fat intake increases the risks for coronary

artery disease and certain types of cancer, both related to and independent of obesity

40

(Wadden, Foster, Stunkard, Conill, 1996). On the other hand, low-fat intake can improve

risk factors for coronary artery disease, such as dyslipidemia, and results in weight loss

without food deprivation. Therefore, it seems prudent to suggest restriction of dietary fat

especially in the obese population.

In obese post-menopausal women, an ECWM diet containing a decreased fat-tocarbohydrate ratio may enhance weight loss and significantly increase energy

expenditure. Macronutrient composition of the diet, an important determinant of

metabolic efficiency can indirectly induced weight loss by inducing a negative caloric

balance. Further studies that carefully control for the macronutrient metabolic efficiency

and ECWM will elucidate the efficacy of low fat diets on REE and weight loss in normal

versus obese post-menopausal women.

41

REFERENCES

Abbot W.G.H., Howard, B.V., Ruotolo, G., Ravussin, E. (1990). Energy expenditure in

humans: effects of dietary fat and carbohydrate. American Journal of Physiology,

258: E347-51.

Amenorrhoea. (n.d.) Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition. (2009). Retrieved

from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/amenorrhoea

Astrup, A., Buemann B., Christensen, N.J., Madsen, J. (1994). 24-hour energy

expenditure and sympathetic activity in postobese women consuming a

high-carbohydrate diet. American Journnal of Physiology, 226, E592599.

Barrett-Connor, E., Friedlander N.J. (1993). Dietary fat, calories, and the risk

of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: a prospective populations

based study. Journal of American Coll Nutrition, 12, 390-9.

Blundell, Caudwell, Gibbons, Hopkins, Naslund, King, and Finlayson, (2011).

Body Composition and appetite: fat-free mass (but not fat mass of

BMI) is positively associated with self-determined meal size and daily

energy intake in humans. British Journal of Nutrition, 107(3):445-9.

Bray & Pompkin, (1998). Dietary fat affects obesity rate. American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, 68(6): 1157-73.

42

Brehm, Seeley, Daniels, D’Alessio, (2003). A randomized trial comparing a

very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body

weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. Journal of

Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 88(4):1617-23.

Brehm, Spang, Lattin, Seeley, Daniels et al. (2005). The Role of Energy

Expenditure in the Differential Weight Loss in Obese Women on Low-Fat

and Low-Carbohydrate Diets. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and

Metabolism, 90 (3): 1475.

Chapman, Bannerman, Cowen, & Maclennan, (1998). The relationship of anthropometry

and bio-electrical impedance to dual-energy X- ray

absorptiometry in elderly men and women. Age and Ageing, 27: 363 –

367.

Compher, Frankenfield, Keim, Roth-Yousey, (2006). Best practice methods to

apply to measurement of resting metabolic rate in adults: a systematic

review. Journal of the American Diet Association, 106(6):881-903.

Cunningham, JJ. (1980). A reanalysis of the factors influencing basal metabolic

rate in normal adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 33:23722374.

Gallagher & Song, (2003). Evaluation of body composition: practical guidelines.

Primary Care. 30(2):249-65.

43

Hegsted, D.M., Ausman, L.A., Johnson, J.A., Dallal, D.E. (1993). Dietary fat and

serum lipids: an evaluation of the experimental data. American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, 57: 875-83.

Heyward V.H., Wagner, D.R. (2004). Applied Body Composition Assessment.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. pp. 87–98.

Hill, JO. (2006). Understanding and addressing the epidemic of obesity: an energy

balance perpective. Endocrine Reviews, 27(7), 750-761.

Hill, Sparling, Shields, & Heller, (1987). Effects of exercise and food restriction

on body composition and metabolic rate in obese women. The American

Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 46(4), 622-630.

Horton, Drougas, Brachey, et al. (1995). Fat and carbohydrate overfeeding in

humans: different effects on energy storage. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition, 62, 19–29.

Lean M.E.J., James W.P.T., (1988). Metabolic effects of isoenergetic nutrient

exhange over 24 hours in relation to obesity in women. International

Journal of Obesity; 12, 15-27.

Leibel, R.L., Hirsch J., Appel, B.E., Checani, G.C. (1992). Energy intake required to

maintain body weight is not affected by wide variation in diet composition.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 55, 350-5.

Lissner, L., Levitsky, D.A., Strupp, B.J., Kalkwarf, H.J., Roe, D.A. (1987). Dietary

fat and the regulation of energy intake in human subjects. American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, 46, 886-92.

44

Martin, L.J., Su, W., Jones, P.J., Lockwood, G.A., Tritchler, D.L., Boyd, N.F.

(1996). Comparison of energy intakes determined by food records and

doubly labeled water in women participating in a dietary-intervention

trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 63, 483-90.

Noakes, Keogh, Foster, and Clifton, (2005). Effect of an energy-restricted, highprotein, low-fat diet relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate, low-fat

diet on weight loss, body composition, nutritional status, and markers of

cardiovascular health in obese women. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition, 81(6) 1298-1306.

Prewitt, Schmeisser, Bowen, Aye, Dolecek, Langenberg, Cole & Brace, (1991).

Changes in body weight, body composition, and energy intake in women

fed high- and low-fat diets. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 54,

304-310.

Rising, Tataranni, Snitker, Ravussin, (1996). Decreased ratio of fat to

carbohydrate oxidation with increasing age in Pima Indians. Journal of the

American College of Nutrition, (3):309-12.

Roust, Hammel, & Jensen, (1994). Effects of isoenergetic, low fat diets on energy

metabolism in lean and obese women. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition, 60, 470-475.

Sacks, Bray, Carey, Smith, Ryan et al. (2009). Comparison of Weight Loss Diets with

Different Compositions of Fat, Protein and Carbohydrates. New

England Journal of Medicine. 360:859-873.

45

Segal, Van Loan, Fitzgerald, Hodgdon & Van Itallie, (1988). Lean body mass

estimation by bioelectrical impedance analysis: a four- site crossvalidation study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 47, 7-14.

Stubbs, William, Coward, Prentice, (1995). Convert manipulation of the ratio of

dietary fat to carbohydrate and energy density: effect on food intake and

energy balance in free-living men eating ad ibitum. American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, 62:330-7.

Volek, Sharman, Gómez, Judelson, Rubin, Watson, Sokmen, Silvestre, French &

Kraemer (2004). Comparison of energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate

and low fat diets on weight loss and body composition in overweight men

and women. Nutrition and Metabolism, 1:13 doi:10.1186/1743-7075-1-13.

Wadden, Foster, Stunkard, Conill, (1996). Effects of weight cycling on the

resting energy expenditure and body composition of obese women.

International Journal of Eating Disorders; 19: 5-12.

Weir, J.B. de V. (1949): New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special

reference to protein metabolism. Physiology. 109, 1—9.

World Health Organization, (1998). Obesity: Preventing and Managing the

Global Epidemic (World Health Organization, Geneva).