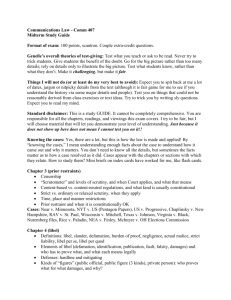

Code of Ethics for Journalism - Mira Stauffer

advertisement

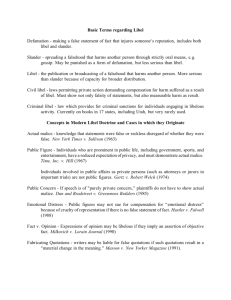

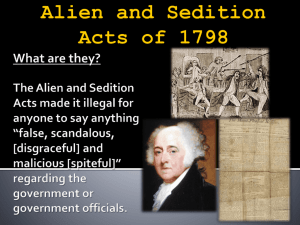

From the Associated Press Stylebook MEDIA LAW WHAT IS LIBEL? At its most basic, libel means injury to reputation. Words, pictures, cartoons, photo captions and headlines can all give rise to a claim for libel. Emotional distress is also an element of damages in libel. WHAT IS LIBEL? The omission of names will not, in itself, provide a shield against a claim for libel. There may be enough details for the person to be recognizable. The fact that police are questioning someone about a crime does not necessarily justify the label suspect. WHAT IS LIBEL? The publisher of a true and accurate quote of a statement containing libelous allegations is NOT immune from suit A newspaper can be called to task for republishing the libelous statement of another. JOURNALISTIC PRIVILEGES: 1. Opinion The rationale behind the opinion privilege is that only statements that can be proven true or false are capable of defamatory meaning and that statements of “opinion” cannot, by their nature, be proven true or false. Statements incapable of being proven false are considered protected expressions of opinion, as are epithets, satire, parody and hyperbole. To be protected under the opinion privilege, the content, tone and apparent purpose of the statement should signal the reader that the statement reflects the author’s opinion. OPINION PRIVILEGE: One test followed in many states for distinguishing fact from opinion asks: (1) whether the statement has a precise core of meaning on which a consensus of understanding exists; (2) whether the statement is verifiable; (3) whether the textual context of the statement would influence the average reader to infer factual content; (4) whether the broader social context signals usage as either fact or opinion. OPINION PRIVILEGE: In California, a false assertion of fact could be libelous even though couched in terms of opinion, although statements that are clearly satirical, rhetorical, or hyperbolic continue to be protected. This is in direct contrast to New York’s approach. California held that three questions should be considered to distinguish opinion from fact: (1) does the statement use figurative or hyperbolic language that would negate the impression that the statement is serious? (2) does the general tenor of the statement negate the impression that the statement is serious? (3) can the statement be proved true or false? OPINION PRIVILEGE: Opinions that are offered in a context that presents the facts on which the opinion is based are generally not actionable. Opinions that imply the existence of undisclosed, defamatory facts (if you knew what I know) are more likely to be actionable. A statement that is capable of being proven true or false, regardless of whether it is expressed as an opinion or as an exaggeration or even hyperbole, may be actionable. JOURNALISTIC PRIVILEGES: 2. Fair Comment and Criticism Everyone has a right to comment on matters of public interest and concern, provided they do so fairly and with an honest purpose. Such comments or criticism are not libelous, however severe in their terms, unless they are written maliciously. JOURNALISTIC PRIVILEGES: 3. Fair Report A fair and accurate report of a public proceeding cannot provide grounds for a libel suit This privilege relieves a news organization of responsibility for determining the underlying truth of the statements made in these contexts, precisely because the very fact that these comments were made is newsworthy and important regardless of whether they are actually true. FAIR REPORT: Examples: news report based on information provided by police sources; judicial proceedings; an official proceeding to administer the law; all executive and legislative proceedings; the proceedings of public meetings dealing with public purposes. California also includes press conferences. FAIR REPORT: Exceptions: Statements made on the floor of convention sessions or from speakers’ platforms organized by private organizations. Statements made outside the court by police or a prosecutor or an attorney may or may not qualify as privileged, depending on the state and the circumstances in which the statements are made. Statements made by the president of the United States or a governor in the course of executive proceedings have absolute privilege for the speaker (even if false or defamatory), the press’ privilege to report all such statements is not always absolute. JOURNALISTIC PRIVILEGES: 3. Neutral Reportage Protects a fair, true and impartial account of a newsworthy event. This privilege relieves a news organization of responsibility for determining the underlying truth of the statements made in these contexts, precisely because the very fact that these comments were made is newsworthy and important regardless of whether they are actually true. DEFENSES AGAINST LIBEL: 1. Not Capable of Defamatory Meaning This privilege relieves a news organization of responsibility for determining the underlying truth of the statements made in these contexts, precisely because the very fact that these comments were made is newsworthy and important regardless of whether they are actually true. DEFENSES AGAINST LIBEL: 2. Truth Most libel plaintiffs will have to prove that the statement about which they complain is false, but a libel defendant’s best defense is that the statement is true and published without malicious intent. DEFENSES AGAINST LIBEL: 2. Fault Some showing of fault on the part of defendant is a predicate to any recovery in a defamation action. Differs for public vs. private individuals: there are more risks to publishing matters not of legitimate public concern about private individuals than to publishing matters that are of public concern, especially where they involve public figures or public officials. PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS: Public individuals: If the plaintiff is a public figure or public official, the plaintiff must establish by clear and convincing evidence that the publication was made with actual malice. It inquires into whether the publisher believed the statement was false or whether he published it with reckless disregard for its truth, or with awareness of a high probability that the statement was false. PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS: Private individuals: whether the defendant should have known, through the exercise of reasonable care, that a statement was false FIRST AMENDMENT RULES The Public Official Rule: The press enjoys a great protection when it covers the affairs of public officials. In order to successfully sue for libel, a public official must prove actual malice. This means the public official must prove that the editor or reporter had knowledge that the facts were false or acted with reckless disregard of the truth. FIRST AMENDMENT RULES The Public Figure Rule: The rule is the same for public figures as public officials. A public figure must prove actual malice. In general, there are two types of public figures: 1. General Purpose Public Figure: An individual who has assumed the role of special prominence in the affairs of society and occupies a position of persuasive power and influence. Example: Jay Leno 2. Limited Purpose Public Figure: A person who has thrust himself or herself into the vortex of a public controversy in an attempt to influence the resolution of the controversy. Example: an abortion protester on a public street in the vicinity of an abortion clinic was considered a limited purpose public figure FIRST AMENDMENT RULES The Private Figure Rule: Someone who is not a public figure. Law for libel suits brought by private figures varies from state to state. A number of states (Alaska, Colorado, Indiana and New Jersey) follow the same rule for private figures and public figures. They require private figures to prove actual malice. New York requires private figures to prove that the publisher acted in a “grossly irresponsible manner” when the matter published is of public concern. Most states require private figures to prove only “negligence.” A careless error on the part of the journalist could be found to constitute negligence. DEFAMATION OF THE DEAD Most states do not recognize a cause of action for defamation of the dead. Many states, do, however, permit an ongoing libel suit to continue after the death of the complaining person. For example, in New York no one can bring a cause of action for defamation of a deceased person unless they can demonstrate that their own reputation has been damaged by the defamation of the deceased. REVIEW When you have any concerns about any particular statement or opinion, the first question to ask is: is whether it is capable of defamatory meaning. Second, does it refer to a specific, identifiable individual? Third, do any privileges apply? Does the opinion privilege apply? What about the fair report privilege? Does the state recognize any other privilege, such as fair comment and criticism of public officials ,or the neutral report privilege? Fourth, is the individual identified a public figure or a public official? Fifth, is the topic of the article one of public concern? Finally, what investigation was done in the preparation of the article and what sources does the article rely on?