Essays on slurs

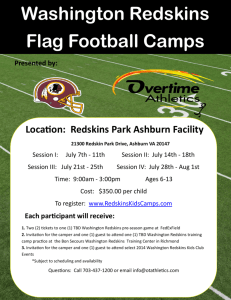

advertisement

As you read… 1) SCOPE annotate (summarize, make connections, opinions, pose questions, examine word choice) 2) highlight researched information one color 3) highlight the author’s personal opinion in another. A Note On The Word "Nigger" By Randall Kennedy, Professor of Law, Harvard University The word "nigger" is a key term in American culture. It is a profoundly hurtful racial slur meant to stigmatize African Americans; on occasion, it also has been used against members of other racial or ethnic groups, including Chinese, other Asians, East Indians, Arabs and darker-skinned people. It has been an important feature of many of the worst episodes of bigotry in American history. It has accompanied innumerable lynchings, beatings, acts of arson, and other racially motivated attacks upon blacks. It has also been featured in countless jokes and cartoons that both reflect and encourage the disparagement of blacks. It is the signature phrase of racial prejudice. To understand fully, however, the depths and intensities, quirks and complexities of American race relations, it is necessary to know in detail the many ways in which racist bigotry has manifested itself, been appealed to, and been resisted. The term "nigger" is in most contexts, a cultural obscenity. But, so, too are the opinions of the United States Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which ruled that African Americans were permanently ineligible for federal citizenship, and Plessy v. Ferguson, which ruled that state-mandated, "equal but separate" racial segregation entailed no violation of the federal constitution. These decisions embodied racial insult and oppression as national policy and are, for many, painful to read. But teachers rightly assign these opinions to hundreds of thousands of students, from elementary grades to professional schools, because, tragically, they are part of the American cultural inheritance. Cultural literacy requires detailed knowledge about the oppression of racial minorities. A clear understanding of "nigger" is part of this knowledge. To paper over that term or to constantly obscure it by euphemism is to flinch from coming to grips with racial prejudice that continues to haunt the American social landscape. Leading etymologists believe that "nigger" was derived from an English word "neger" that was itself derived from "Negro", the Spanish word for black. Precisely when the term became a slur is unknown. We do know, however, that by early in the 19th century "nigger" had already become a familiar insult. In 1837, in The Condition of the Colored People of the United States; and the Prejudice Exercised Towards Them, Hosea Easton observed that "nigger" "is an opprobrious term, employed to impose contempt upon [blacks] as an inferior race…The term itself would be perfectly harmless were it used only to distinguish one class from another; but it is not used with that intent…it flows from the fountain of purpose to injure." The term has been put to other uses. Some blacks, for instance, use "nigger" among themselves as a term of endearment. But that is typically done with a sense of irony that is predicated upon an understanding of the term’s racist origins and a close relationship with the person to whom the term is uttered. As Clarence Major observed in his Dictionary of Afro-American Slang (1970), "used by black people among themselves, [nigger] is a racial term with undertones of warmth and goodwill – reflecting…a tragicomic sensibility that is aware of black history." Many blacks object, however, to using the term even in that context for fear that such usage will be misunderstood and imitated by persons insufficiently attuned to the volatility of this singularly complex and dangerous word. Some observers object even to reproducing historical artifacts, such as books or cartoons, that contain the term "nigger." This total, unbending objection to printing the word under any circumstance is by no means new. Writing in 1940 in his memoir The Big Sea, Langston Hughes remarked that "[t]he word nigger to colored people is like a red rag to a bull. Used rightly or wrongly, ironically or seriously, of necessity for the sake of realism, or impishly for the sake of comedy, it doesn’t matter. Negroes do not like it in any book or play whatsoever, be the book or play ever so sympathetic in its treatment of the basic problems of the race. Even though the book or play is written by a Negro, they still do not like it. The word nigger, you see, sums up for us who are colored all the bitter years of insult and struggle in America." Given the power of "nigger" to wound, it is important to provide a context within which presentation of that term can be properly understood. It is also imperative, however, to permit present and future readers to see for themselves directly the full gamut of American cultural productions, the ugly as well as the beautiful, those that mirror the majestic features of American democracy and those that mirror America’s most depressing failings. For these reasons, I have advised the management of HarpWeek to present the offensive text, cartoons, caricatures and illustrations from the pages of Harper's Weekly, as well as other politically sensitive nineteenth-century material, as they appeared in their historical context. This same advice holds for slurs relating to Irish, Chinese, Germans, Native Americans, Catholics, Jews, Mormons and other ethnic and religious groups. As you read… 1) SCOPE annotate (summarize, make connections, opinions, pose questions, examine word choice) 2) highlight researched information one color 3) highlight the author’s personal opinion in another. Op-ed: It's Time to Stop With The T Word Some may think using the t word is permissible, but trans women who are the target of the hate that the word conjures don't necessarily agree. BY PARKER MARIE MOLLOY PARKER MARIE MOLLOY is the founder of Park That Car and works as a freelance writer. She has contributed writing to Rolling Stone, Salon, The Huffington Post, and Talking Points Memo as well as The Advocate. Follow her on Twitter @ParkerMolloy. Last year I wrote a piece on The Huffington Post titled “Gay Dudes, Can You Just Not?” that generated digital eye rolls, nasty comments, and even threats from readers. It was critical of use of the word “tranny” by gay and bisexual men. The central idea was that the word, which I’ll now simply refer to as “the t slur,” is, in fact, a slur. It’s a term tied to a history of violence, oppression, anger, and hate. It’s a term I’ve been called by those who wish to harm me. And frankly, it’s a term many trans women, like slain New Yorker Islan Nettles, hear immediately prior to falling victim to physical violence. I dared to inform those who use the word, who think they have a “pass” on account of themselves being part of the “LGBT community,” that it’s not their word to use, and it’s not their slur to “reclaim.” As expected, response to my essay was dismissive and hostile. “The author is way off base,” one commenter wrote. “The word is just a shortened version of ‘transvestite,’ which is another description of a drag queen,” another said. “Words are just words,” said another. And referring to the use of the t slur on Glee, someone wrote, “You can easily tell that the kids of Glee were saying it out of love in the classroom,” and telling me to “lighten up, grow up.” I never fully got the opportunity to refute the things said in those comments. But it’s that time of year again, when RuPaul’s show heads back to the cable, and the already high level of transphobic content on television spikes. So what better time than now to tackle this issue again? Leela Ginelle at PQ Monthly described the conversation following my previous essay as “breaking the queer corner of the Internet.” Here’s my attempt at putting it back together with a warning: fragile. RuPaul and others contend that the t slur isn’t aimed at trans women, and therefore, he, as a cisgender, gay man, is welcome to use the term as he sees fit. He’s gone so far as to denounce those who have apologized for using the term. “It’s ridiculous! It’s ridiculous!” RuPaul told The Huffington Post’s Michelangelo Signorile in 2012. “I love the word ‘tr*nny.’" Elsewhere in that same interview, RuPaul became exasperated when discussing the cancelation of the short-lived ABC sitcom Work It, a show that seemed on track to become the most transphobic piece of media to hit network TV. “We live in a culture where everyone is offended by everything,” he told The Huffington Post. “Everybody’s like, ‘Oh my god, I’m offended!’” He continues, “In my circle of friends, we mock everything! Everything is up to be mocked. Don’t take life too seriously. … If you’re offended by a name that somebody calls you, or something, whatever, you gotta take that up with your therapist, kiddo.” And, in possibly the most ludicrous statement ever constructed, RuPaul said, “No one has ever said the word ‘tr*nny’ in a derogatory sense.” Is that so? So when I sat in the only open seat on a crowded train in the months after coming out as transgender, when the woman next to me said into her phone, “Some f*ing tr*nny just sat next to me” and decided to stand rather than remain next to me — that wasn’t her being derogatory? When a group of college kids called me a “tr*nny faggot” as I waited for a bus, triggering a panic attack that left me home sick from work for two days — that wasn’t them being derogatory? If only I knew that they meant it in a loving, happy way, oh, how things could have been different! The fact of the matter, Ru, is that words do hurt, and when you continue to use words that are frequently used to dehumanize people like me, that are used as precursors for assault, after you’ve been informed how hurtful these words are, you’re no better than a racist who uses the “n word,” the homophobe who calls gay men “faggots,” or the misogynist who refers to his female coworkers as “b*tches.” And yes, readers, before you start with the, “but I know several trans friends who refer to themselves as that,” or “I know trans people who don’t find that word offensive,” I’m going to have to stop you right there. Your friend, acquaintance, family, coworker, or Starbucks barista may not have a problem with the t slur, but a lot of trans people do. I listened to a Kanye West album, and he’s throwing the n word around like it’s going out of style. Does that mean I, as a white woman, should feel free to use the word? Of course not. Why? Because it’s not my word to use, just as the t slur is not yours to use. And finally, there’s the time-tested excuse: “I am trying to ‘reclaim’ the word.” How kind of you. Thank you so very much, but unfortunately, unless you’re a member of the group that finds itself most negatively impacted by a slur, it’s not yours to reclaim. The n-word cannot be reclaimed by someone who isn’t black, “faggot” cannot be reclaimed by someone who isn’t a gay man. “Dyke” cannot be reclaimed by someone who isn’t a lesbian. “Bum” cannot be reclaimed by someone who isn’t homeless. And thus, the t slur cannot be reclaimed by anyone other than transgender women. Transgender women are the ones who find themselves so frequently at the receiving end of abuse related to this word. When you hear that word, whether it’s being used on a sitcom like How I Met Your Mother or Mike & Molly, the image being evoked is that of what the public sees as the stereotypical trans woman. The joke, as used on these shows, is often of the “ha ha, you almost slept with a tr*nny” variety. The punch line of the joke is that one of the characters, often a straight man, finds himself attracted to a trans woman, and that is just inherently funny for some reason. Because the word is predominantly aimed at trans women, with us as the joke, it is only trans women who can “reclaim” it if we so choose. While I’m certain some trans men have had the word thrown at them, it’s not theirs to reclaim. While I’m sure drag queens have had the word thrown at them, they have the benefit of being able to wash off their makeup, take off their dress, and fade back into their male lives. I don’t have that luxury. This is my life. This is my identity, not an activity, and not a hobby. This is who I am, forever trans, forever vulnerable to the damage this word can cause. “But Parker,” you ask. “Aren’t there bigger issues to worry about? What about the startlingly high rate of trans suicide attempts, or the number of homeless trans youth, or the number of trans women of color who find themselves the victims of physical violence? Why are you so hung up on a word? It’s just a word.” Well, my inner devil’s advocate, you’re absolutely right. Those are important issues, and addressing those should take precedence over whether I have a panic attack after being called the t slur. This isn’t about panic attacks, this is about the systemic dehumanization of trans people. When someone is no longer treated as though they have a shred of humanity in them, they become easier to attack. It’s the same reason people often use the phrase “born a man” to describe trans women. When someone has a baby, finding “It’s a boy!” and “It’s a girl!” cards is no problem. I ask you to try to find a card that reads, “It’s a man!” You can’t. It’s for this reason that trans people are treated as though they never had the innocence brought on by childhood: it’s easier to attack someone if you don’t view them as ever having been “pure.” When it comes to morally justifying emotional and even physical attack, a man will always be easier to attack than a boy; a woman will always be easier to attack than a girl; a t slur will always be easier to attack than a human being. When you use these words, and when you disregard the concerns that have been brought to you by both trans individuals themselves as well as organizations like GLAAD, you contribute to those larger problems: homelessness, violence, poverty, and more. The new season of RuPaul's Drag Race could be used as a chance to change. Based on past comments — and there hasn't been anything said publicly since that Huffington Post interview— it doesn't seem likely. Miracles could happen, though, who knows. In the meantime, RuPaul, you dehumanize us, and you teach the public that it’s OK to do the same. Once we’re no longer people, once we’re simply t slurs, it’s easy for society to toss us aside, to discriminate against us and beat us, to deny us care and send us to the streets. I’m a human being, not a tr*nny. Knock it off. As you read… 1) SCOPE annotate (summarize, make connections, opinions, pose questions, examine word choice) 2) highlight researched information one color 3) highlight the author’s personal opinion in another. "Redskins": A Native's Guide To Debating An Inglorious Word Gyasi Ross is a member of the Blackfeet Indian Nation and also comes from the Suquamish Nation. Both are his homelands. He continues to live on the lovely Suquamish Reservation—contrary to Rick Reilly's assertion, no white liberals influenced his writing of this article. He is a father, an author, a lawyer, and a warrior. He has a new book, How To Say I Love You in Indian, available for pre-order. His Twitter handle is @BigIndianGyasi. He is a Seahawks fan and sees the Redskins as an inferior team, but readily acknowledges RGIII's potential greatness (and hopes Alfred Morris does well because Morris is on his fantasy football team). Three days ago, in his halftime essay for Sunday Night Football, Bob Costas called the "Redskins" nickname an "insult" and a "slur," joining a chorus of people— from the Washington Post to Slate to Keith Olbermann to even President Obama—suggesting or demanding that the team change its name. That's cool, and you tend to believe that they're bringing this up as a matter of social justice. Still, as a Native American writer and lawyer who 1) speaks, through various media, to educated/scholarly Native Americans, but also 2) lives on a reservation and was born and raised on various reservations where there are decidedly different interests from those of the Native intelligentsia, I find the recent mainstream attention to the Washington Redskins both encouraging and suspicious. FYI: It's not a new topic among Native people; there have been those who have been encouraging this discussion literally for decades. I wanted to give a quick primer on that discussion for those who are interested, separating some of the mythology of the Washington Redskins mascot controversy from the reality. It's not quite as clear as it seems, in either direction. And like many social justice movements historically, the allegedly aggrieved—Native Americans—haven't come to anything resembling a consensus on this topic. (Don't believe the hype.) That doesn't mean that it's not a social justice issue, though. Confusing, right? Exactly. The vast majority of Native people do not sit around wishing the Redskins would change their name. Most don't care about this topic. Some do. Some actually like the name. Either way, there's no consensus at all. A quick story: My first foray into illicit gambling came when I was in third grade and living on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana. The Blackfeet Reservation is large and beautiful, struggles economically and has health indicators pointing in the wrong direction. There is 70 percent unemployment there, and about 26 percent of the population earns less than the poverty guideline. Despite these numbers and despite growing up with a single mom, I conjured up five bucks to make a bet on Super Bowl XVIII with my good buddy Alan Spoon. I didn't know anything about football, but I had a particular interest in the game—there were some Indians playing. Right? That's what their helmets said. Anyway, here we were, two Indian boys: We literally fought to see who got the Redskins. He won the fight. He got the Redskins. I got his five bucks. I never really thought about that fateful moment until this year. A couple of weeks ago, I was watching the Redskins get their asses handed to them by the Eagles. I have Alfred Morris on my fantasy football team and wanted him to get the ball back, so I was cheering for the Eagles to score quickly. My son was screaming, "Stop them, Redskins!" I didn't even know he was watching the game. When he started cheering for them, I figured that he was simply antagonizing me, as he is wont to do. I asked him, "Why do you always cheer against the team that I'm cheering for?" He told me, quite matter-of-factly: "I want the Redskins to win. I like the Redskins. They have an Indian on the helmet." Obviously, this is totally anecdotal, and not all Native people feel this way. Not remotely. However, it is safe to say that the Washington Redskins logo is realistic and handsome (unlike the coonish Cleveland Indians mascot) and there is an intuitive pull for many Native people who see that logo. Further, Native people are among the poorest people in this nation, despite the casino stereotype that many non-Natives hold. We also have, as most impoverished groups do, serious issues with fatherlessness, substance abuse, and suicide. As a result, most Native people have pretty serious things to worry about other than a football team's mascot. Still, there is a legitimate and valid minority of Native people who are very concerned about the Redskins. The Oneida Nation, for example, recently paid for some radio ads to work to take down the Washington Redskins name. There is no unanimity of thought here. Which leads me to point No. 2: The anti-Redskins movement is driven by a small percentage of Native people. As a result of the "very serious other concerns" enumerated above, most Native people simply don't really have the bandwidth to push the anti-Redskins agenda, even if they wanted to. A lot of us simply cannot afford to have this in our lists of things to do today. Thus, the topic has been championed by a very small group of Natives who do not have to worry about the lower tiers in Maslow's hierarchy. Many of us, even those who agree with that stance, are simply too busy keeping the lights on to worry too much about mascots. Anecdotally, there is plenty of support for other Native mascots. Indeed, if a person were to take a poll of reservation/Indian schools, that person would find that a whole bunch the school mascots were Indian in nature: Browning Indians, Haskell Indians, Flandreau Indians, Plenty Coups Warriors, the Hoonah Braves, etc. No such poll exists, of course, but the continued existence of tribal schools with "Indian"-themed mascots is instructive. The point: Most Native people have no inherent problem with Indian mascots; what matters is the presentation of that mascot and name. The presentation of the name "Redskins" is problematic for many Native Americans because it identifies Natives in a way that the vast majority of Natives simply don't identity ourselves. Every other ethnic group gets the opportunity to self-identify in the way they choose. Native people do not. The NFL and fans of the NFL treat Native people qualitatively differently from how they treat members of any other ethnic group. Whether or not the term "Redskin" is inherently racist is the wrong question. The more appropriate question is, "Would it be acceptable to name a professional sports team according to the color of someone else's skin?" Would it ever be cool to have a sports team called the Washington Blackskins? It seems appropriate; D.C. is Chocolate City. But, um, heck no. San Francisco Yellowskins? Naw, cousin. Won't work. None of the above would be cool. OK, how about a high school team called the Paducah Negroes? "Negroes" is a term that is not necessarily racist, yet black folks choose not to identify themselves as such. People respect black folks' choice not to call themselves Negro and so people don't call them by that name. Yet, it's different with Native people. Somehow non-racist black folks, white folks, and Latinos feel that it's OK to identify Natives in a way that we simply do not—and do not want to—identify ourselves. If that is not racist, it is at the very least incredibly racially insensitive. There is some internal value to the Redskins name, just as there is some internal value to the word "nigger." Like "redskin," "nigger" has a fairly innocuous origin (it derives from the Spanish word for "black"), but picked up barbed and offensive connotations as it passed through history. As hurtful as the word "nigger" is, though, it has value to a certain percentage of African-Americans, as evidenced by the usage of the word as a term of affection (or sometimes simply as an identifier, even absent affection). People can, and do, argue passionately about whether or not the word should be used, whether it is appropriate or foul. Still, however one concludes, the word's still there. It has significance and currency to at least some percentage of black folks. Similarly, for centuries, some Native people have used the word "Redskin" (and its variations) as an identifier. Still do. The word unquestionably predates the current conversation and even the supposed genesis of the term in the very real scalping policies of the 19th century, when white bounty hunters were paid for scalps only when they proved their Indian origin by showing the red skin. (Here's the Los Angeles Herald in 1897: "VALUE OF AN INDIAN SCALP: Minnesota Paid Its Pioneers a Bounty for Every Redskin Killed.") Those scalpings were a tragic and ugly episode in American history, and at the very least a certain solemnity of tone is called for in making even oblique reference to them. But they are not tied to the origin of the word. Indeed, the word goes back quite a bit further than that era, and has been used as a self-identifier since at least the mid-1700s, when the Piankashaws referred to themselves and other Natives as "redskins." More anecdotally, many modern-day Natives refer to themselves and other Natives as "Skins" as a term of selfassociation. (It's a derivative, with the same relation to the original that "nigga" bears to "nigger.") The column that I typically write for Indian Country Today Media Network is called "The Thing About Skins," and "red" is an accepted term of affinity and familiarity among Native peoples. Terms such as "red road," "red pride," and "red man" have been used for some time within our communities. Recently a group called A Tribe Called Red (!) remixed a popular pow-wow song called "Redskin Girl" as a further show of that affection and familiarity. Not all Natives use these terms, just like not all black folks use the term "nigger" (or "nigga"). Some do. But everyone recognizes that the word carries a certain potency. (Little known fact: New York City actually symbolically banned the word "nigger" in 2007 because of this potency. That action triggered a highly spirited internal debate about the merits of the word among academics and activists.) Even words with value internally can be racist when used externally. The "redskins" topic, as you may begin to notice, is similar to the "nigger" debate, which has launched an entire cottage industry devoted to debating the use of the word in pop culture—books, album names, television specials, academic discussions. That there is still a lively debate on the subject tells you that the words still retain their value, their power. Yet, there is a crucial difference: It is black folks who debate the merits and demerits of the word "nigger." White folks understand that, as a matter of propriety, it would be the ultimate in tastelessness and disrespect to take the lead in the discussion of the word "nigger." Yet, here are outsiders—black, white, Asian, Latino—telling Native people how we should feel about the word "redskins" and what we should be offended by. If white people tried to pull the "we're going to tell you what words you should be offended by" stuff with the word "nigger," there would, as NWA eloquently put it above, be serious problems. Apparently, though, while it's racist and condescending to tell some people what should offend them, it's somehow OK to do the same with Native people. I actually appreciate Rick Reilly's perspective when he says he wants to keep nonNative liberals from driving this discussion. It's a fair point, and it shows at least some awareness of who has a real stake in the outcome. There is certainly a decent amount of liberal absolution at work here, too, even if it's bound up with a creditable forbearance on the part of white liberals regarding the use of freighted language that doesn't belong to them. Still, it's not Rick Reilly's job to discern who is talking for whom. If he sees a Native person talking, he should probably assume that the Native person is talking for himself or herself. Would Reilly argue that white people are free to use the word "nigger" because white liberals largely led the movement that pushed white people to stop using it in everyday conversation? Notice the disconnect? Which leads me to my final point: The "Redskins" debate is similar to the "nigger" debate, yet unlike with the "nigger" debate, outsiders feel perfectly comfortable telling Native people how they should feel. I suppose that's the most frustrating part of the debate—that we Native people, the folks who are the only meaningful stakeholders in this debate—are not allowed to have a voice in the matter. Correct that: We can have an opinion so long as it is pro-Redskin. Otherwise, we're being "too sensitive." No non-black person has ever, EVER called a black person a "nigger" in recent times and then told that black person that he was being "too sensitive" if/when he got upset. NO non-black person uses the internal value of the word "nigger" as a justification for a nonblack person to keep using the word. NO non-black person says, "The word 'nigger' was pretty harmless at one time, therefore I'm going to just throw it around a bit. Try it out. See if it works for me." NO non-black person has ever gone rummaging through American cities in search of a black person who's not offended by the word "nigger," and then held them up as proof that the word isn't so bad. ("See? There are some black folks that aren't offended by the word, therefore it CAN'T BE racist.") Doesn't happen. Why not? Because black folks decided that they wouldn't stand for the word anymore, and it's now understood that "nigger" belongs to black folks. It's theirs to do with as they wish, and it's simply racist when other groups use it. If black people choose to use it, that's their business—they've paid a heavy price to own that word. Similarly, "redskins" is Native people's word. If it's unfortunate and sad that we use it, hey, that's our choice. We paid the price for this racist and loaded term. Instead, we have a bunch of white men telling us that it's not racist, and a bunch of black folks who continue to think that it can't be racist because it's black men wearing the jerseys and, hey, it's just a football team. That's the frustration—the voicelessness and inequality in treatment, and the people who don't see how this is like non-black folks using the word "nigger," who don't even think that it might be racist. Heck, many Natives are just like me—not particularly concerned about the whole affair. It's not the biggest deal in the world. Yet even those of us who are indifferent have to look and notice the disparity in treatment. Every other racial group can— and should be able to—say what is offensive to them without being called "too sensitive." We cannot. That prompts the question: Why not? So I pass that question on to you: At one point, many white people openly called black people "niggers." Those racists stopped, eventually, because many (not all) black people said that word was hurtful and offensive. That was a positive step—progress. In light of that racial progress, why wouldn't folks also stop calling another group of people, Native Americans, a word that many (not all) Native Americans likewise say is hurtful, racist, and offensive? Or, to put it another way: Shouldn't we have gotten to the point where non-racists feel uncomfortable using a word that a contingent of people find hurtful, racist, and offensive? Peace. As you read… 1) SCOPE annotate (summarize, make connections, opinions, pose questions, examine word choice) 2) highlight researched information one color 3) highlight the author’s personal opinion in another. Why 'illegal immigrant' is a slur By Charles Garcia, Special to CNN updated 12:14 PM EDT, Fri July 6, 2012 A supporter of Arizona's immigration policy pickets outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington in April. Editor's note: Charles Garcia, who has served in the administrations of four presidents, of both parties, is the CEO of Garcia Trujillo, a business focused on the Hispanic market. He was named in the book "Hispanics in the USA: Making History" as one of 14 Hispanic role models for the nation. Follow him on Twitter:@charlespgarcia. (CNN) -- Last month's Supreme Court decision in the landmark Arizona immigration case was groundbreaking for what it omitted: the words "illegal immigrants" and "illegal aliens," except when quoting other sources. The court's nonjudgmental language established a humanistic approach to our current restructuring of immigration policy. When you label someone an "illegal alien" or "illegal immigrant" or just plain "illegal," you are effectively saying the individual, as opposed to the actions the person has taken, is unlawful. The terms imply the very existence of an unauthorized migrant in America is criminal. In this country, there is still a presumption of innocence that requires a jury to convict someone of a crime. If you don't pay your taxes, are you an illegal? What if you get a speeding ticket? A murder conviction? No. You're still not an illegal. Even alleged terrorists and child molesters aren't labeled illegals. By becoming judge, jury and executioner, you dehumanize the individual and generate animosity toward them. New York Times editorial writer Lawrence Downes says "illegal" is often "a code wordfor racial and ethnic hatred." The term "illegal immigrant" was first used in 1939 as a slur by the British toward Jews who were fleeing the Nazis and entering Palestine without authorization. Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel aptly said that "no human being is illegal." Migrant workers residing unlawfully in the U.S. are not -- and never have been -criminals. They are subject to deportation, through a civil administrative procedure that differs from criminal prosecution, and where judges have wide discretion to allow certain foreign nationals to remain here. Another misconception is that the vast majority of migrant workers currently out of status sneak across our southern border in the middle of the night. Actually, almost halfenter the U.S. with a valid tourist or work visa and overstay their allotted time. Many go to school, find a job, get married and start a family. And some even join the Marine Corps, like Lance Cpl. Jose Gutierrez, who was the first combat veteran to die in the Iraq War. While he was granted American citizenship posthumously, there are another 38,000 non-citizens in uniform, includingundocumented immigrants, defending our country. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and three other justices, stated: "As a general rule, it is not a crime for a removable alien to remain present in the United States." The court also ruled that it was not a crime to seek or engage in unauthorized employment. As Kennedy explained, removal of an unauthorized migrant is a civil matter where even if the person is out of status, federal officials have wide discretion to determine whether deportation makes sense. For example, if an unauthorized person is trying to support his family by working or has "children born in the United States, long ties to the community, or a record of distinguished military service," officials may let him stay. Also, if individuals or their families might be politically persecuted or harmed upon return to their country of origin, they may also remain in the United States. While the Supreme Court has chosen language less likely to promote hatred and divisiveness, journalists continue using racially offensive language. University of Memphis journalism professor Thomas Hrach conducted a study of 122,000 news stories published between 2000 and 2010, to determine which terms are being used to describe foreign nationals in the U.S. who are out of status. He found that 89% of the time during this period, journalists used the biased terms "illegal immigrant" and "illegal alien." Hrach discovered that there was a substantial increase in the use of the term "illegal immigrant," which he correlated back to the Associated Press Stylebook's decision in 2004 to recommend "illegal immigrant" to its members. (It's the preferred term at CNN and The New York Times as well.) The AP Stylebook is the decisive authority on word use at virtually all mainstream daily newspapers, and it's used by editors at television, radio and electronic news media. According to the AP, this term is "accurate and neutral." For the AP to claim that "illegal immigrant" is "accurate and neutral" is like Moody's giving Bernie Madoff's hedge fund a triple-A rating for safety and creditworthiness. It's almost as if the AP were following the script of pollster and Fox News contributor Frank Luntz, considered the foremost GOP expert on crafting the perfect conservative political message. In 2005, he produced a 25-page secret memorandum that would radically alter the immigration debate to distort public perception of the issue. The secret memorandum almost perfectly captures Mitt Romney's position on immigration -- along with that of every anti-immigrant politician and conservative pundit. For maximum impact, Luntz urges Republicans to offer fearful rhetoric: "This is about overcrowding of YOUR schools, emergency room chaos in YOUR hospitals, the increase in YOUR taxes, and the crime in YOUR communities." He also encourages them to talk about "border security," because after 9/11, this "argument does well among all voters -even hardcore Democrats," as it conjures up the specter of terrorism. George Orwell's classic "Nineteen Eighty-Four" shows how even a free society is susceptible to manipulation by overdosing on worn-out prefabricated phrases that convert people into lifeless dummies, who become easy prey for the political class. News: For immigrant graduates, a 'leap of faith has been answered,' educator says In "Nineteen Eighty-Four," Orwell creates a character named Syme who I find eerily similar to Luntz. Syme is a fast-talking word genius in the research department of the Ministry of Truth. He invents doublespeak for Big Brother and edits the Newspeak Dictionary by destroying words that might lead to "thoughtcrimes." Section B contains the doublespeak words with political implications that will spread in speakers' minds like a poison. In Luntz's book "Words That Work," Appendix B lists "The 21 Political Words and Phrases You Should Never Say Again." For example, destroy "undocumented worker" and instead say "illegal immigrant," because "the label" you use "determines the attitudes people have toward them." And the poison is effective. Surely it's no coincidence that in 2010, hate crimes against Latinos made up 66% of the violence based on ethnicity, up from 45% in 2009, according to the FBI. In his essay "Politics and the English Language," Orwell warned that one must be constantly on guard against a ready-made phrase that "anaesthetizes a portion of one's brain." But Orwell also wrote that "from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase ... into the dustbin, where it belongs" -just like the U.S. Supreme Court did. As you read… 1) SCOPE annotate (summarize, make connections, opinions, pose questions, examine word choice) 2) highlight researched information one color 3) highlight the author’s personal opinion in another. Honky Wanna Cracker? Examining the Myth of Reverse Racism Posted in 2002 by Tim Wise Recently, while I was speaking to a group of high school students, I was asked why I only seemed to be concerned about white racism towards people of color, and not racism from people of color towards whites. We had been discussing racial slurs, and several white students wanted to know why I wasn’t as critical of blacks for using terms like “honky” or “cracker,” as I was of whites for using the infamous n-word. Although such an issue may seem trivial in the larger scheme of things, the challenge posed by the students was important, and allowed a dialogue about the essence of what racism is and how it operates. On the one hand, of course, such slurs are quite obviously offensive and ought not be used. That said, I pointed out that even the mention of “honky” and “cracker” had elicited laughter, and not only from the black students in attendance, but also from other whites. The words are so silly, so juvenile, that they hardly qualify as racial slurs at all, let alone slurs on a par with those that have been historically deployed against people of color. The lack of symmetry between a word like honky and those used against blacks was made readily apparent in an old Saturday Night Live skit with Chevy Chase and Richard Pryor, in which Pryor’s character is applying for a job at a company with no other black employees. Chase’s character has the power to either hire him or not, and wants to make sure that if Pryor is hired, he’ll be able to deal with the potential racial animosity that might come his way at the hands of his white colleagues. To test Pryor’s character’s forbearance, Chase suggests a test for Pryor: namely, he’ll throw out racial epithets and see how Pryor’s character responds. And so it begins, with Chase calling Pryor a number of pretty mild slurs, to which Pryor responds in kind with pretty minor league quips about whites. Then Chase calls Pryor a “porch monkey.” Pryor responds with “honky.” Chase ups the ante with “jungle bunny.” Pryor, unable to counter with a more vicious slur, responds with “honky, honky.” Chase then trumps all previous slurs with “nigger,” to which Pryor responds, “dead honky.” The line elicits laughs, but also makes clear that when it comes to racial verbiage, people of color are limited in the repertoire of slurs they can use against whites, and even the ones of which they can avail themselves sound more comic than hateful. The impact of hearing the anti-black slurs in the skit was of a magnitude unparalleled by hearing Pryor say “honky” over and over. As a white person, I always saw the terms honky or cracker as proof of how much more potent white racism was than any variation practiced by the black or brown. When a group of people has little or no power over you, they don’t get to define the terms of your existence, they can’t limit your opportunities, and you needn’t worry much about the use of a slur to describe you, since, in all likelihood, the slur is as far as it’s going to go. What are they going to do next: deny you a bank loan? Yeah, right. So whereas the n-word is a term used by whites to dehumanize blacks, to “put them in their place” if you will, the same cannot be said of honky; after all, you can’t put white people in their place when they own the place to begin with. Power is like body armor; and while not all whites have the same power, all of us have more than we need vis-a-vis people of color, at least when it comes to racial position. Consider poor whites: to be sure, they are less financially powerful than wealthy people of color; but that misses the point of how racial privilege operates within a class system. Within a class system, people compete for “stuff” against others of their same basic economic status. In other words, rich and poor are not competing for the same homes, loans, jobs or even educations to a large extent. Rich compete against rich, working class against working class and poor against poor; and in those competitions — the ones that take place in the real world — racial privilege attaches. Poor whites are rarely typified as pathological, dangerous, lazy or shiftless to anywhere near the extent the black poor are. Nor are they demonized the way poor Latino immigrants tend to be. When politicians want to bash welfare recipients they don’t pick Bubba and Crystal from the trailer park; they choose Shawonda Jefferson from the projects, with her five kids. Also, according to reports from several states, ever since socalled welfare reform, white recipients have been treated better by caseworkers, are less likely to be bumped off rolls for presumed failure to comply with regulations, and have been given more assistance at finding jobs than their black or brown counterparts. Poor whites are more likely to have a job, and are more likely to own their own home than the poor of color. Indeed, whites with incomes under $13,000 annually are more likely to own their own home than blacks with incomes that are three times higher due to having inherited property. None of this denies that poor whites are being screwed by an economic system that relies on their misery. But they retain a leg up on poor or somewhat better off people of color thanks to racism. It is that leg up that renders the potency of certain prejudices less threatening than others; it is what makes cracker or honky less problematic than slurs used against the black and brown. In response, some might say that people of color can indeed exercise power over whites, at least by way of racially-motivated violence. And indeed such events happen, are totally inexcusable, and deserve punishment like any such violence. And I’m sure to those being victimized, the power of those doing the violence in those instances must seem quite real. Yet there are problems with claiming that this “power” proves racism from people of color is just as bad as the reverse. First, racial violence is also a power whites have, so the power that might obtain in such a situation is hardly unique to non-whites, unlike the power to deny a bank loan for racial reasons, to “steer” certain homebuyers away from living in “nicer” neighborhoods, or to racially profile in terms of policing. Those are powers that can only be exercised by the more dominant group as a practical and systemic matter. Additionally, the “power” of violence is not really power at all, since to exercise it, one has to break the law and subject themselves to probable legal sanction. Power is much more potent when it can be deployed without having to break the law to do it, or when doing it would only risk a small civil penalty at worst. Discrimination in lending, though illegal, is not going to result in the perp going to jail; so too with employment discrimination or racial profiling. Likewise, it’s the difference in power and position that has made recent attempts by American Indian activists in Colorado to turn the tables on white racists so ineffective. Indian students at Northern Colorado University, fed up by the unwillingness of white school district administrators in Greeley to change the name and grotesque Indian caricature of the Eaton High School “Reds,” recently set out to flip the script on the common practice of mascot-oriented racism. Thinking they would show white folks what it’s like to be in their shoes and experience the objectification of being a team icon, indigenous members of an intramural basketball team renamed themselves the “Fightin’ Whiteys,” and donned T-shirts with the team mascot: a 1950s-style caricature of a suburban, middle class white guy, next to the phrase “every thang’s gonna be all white.” Funny though the effort was, it has not only failed to make the point intended, but has been met with laughter and even outright support by white folks. Rush Limbaugh actually advertised for the team’s T-shirts on his radio program, and whites from coast to coast have been requesting team gear, thinking it funny, rather than demeaning, to be turned into a mascot. The difference, of course, is that it’s tough to negatively objectify a group whose power and position allows them to define or redefine the meaning of another group’s attempts at humor: in this case the attempt by Indian peoples to teach them a lesson. It’s tough to school the headmaster, in other words. Objectification works against the disempowered because they are disempowered. The process doesn’t work in reverse, or at least, making it work is a lot tougher than one might think. Turning Indians into mascots has been offensive because it perpetuates the dehumanization of such persons over many centuries, and the mentality of colonization and conquest. It is not as if one group (whites) merely chose to turn another group (Indians) into mascots as if by chance. Rather, it is that whites have consistently viewed Indians as less than human — as savage and “wild” — and have been able to not merely portray such imagery on athletic banners and uniforms, but in history books and literature more crucially. In the case of the students at Northern, they would need to be far more acerbic in their appraisal of whites in order for their attempts at “reverse racism” to make the point intended. After all, “fightin” is not a negative trait in the eyes of most, and the 1950s iconography chosen for the uniforms was unlikely to be seen as that big a deal. Perhaps if they had settled on “slave-owning whiteys,” or “land-stealing whiteys,” or “smallpoxgiving-on-purpose whiteys,” the point would have been made; and instead of a smiling “company man” logo, perhaps a Klansman, or skinhead as representative of the white race–now that would have been a nice functional equivalent of the screaming Indian warrior. Bottom line: you gotta go strong to turn the tables on the man, and irony won’t get it nine times out of ten. Without the power to define another’s reality, Indian activists are simply incapable of turning the tables with well-placed humor. Simply put, what separates white racism from any other form and makes antiblack and brown humor more dangerous than its anti-white equivalent is the ability of the former to become lodged in the minds and perceptions of the citizenry. White perceptions are what end up counting in a white-dominated society. If whites say Indians are savages, be they “noble” or vicious, they’ll be seen in that light. If Indians say whites are mayonnaise-eating Amway salespeople, who the heck’s going to care? If anything, whites will simply turn it into a marketing opportunity. When you have the power, you can afford to be self-deprecating. The day that someone produces a newspaper ad that reads: “Twenty honkies for sale today: good condition, best offer accepted,” or “Cracker to be lynched tonight: whistled at black woman,” then perhaps I’ll see the equivalence of these slurs with the more common type to which we’ve grown accustomed. When white churches start getting burned down by militant blacks who spray paint “Kill the honkies” on the sidewalks outside, then maybe I’ll take seriously these concerns over “reverse racism.” Until then, I guess I’ll find myself laughing at another old Saturday Night Live skit: this time with Garrett Morris as a convict in the prison talent show who sings: Gonna get me a shotgun and kill all the whiteys I see Gonna get me a shotgun and kill all the whiteys I see. And once I kill all the whiteys I see Then whitey he won’t bother me Gonna get me a shotgun and kill all the whiteys I see. See, it just isn’t the same. As you read… 1) SCOPE annotate (summarize, make connections, opinions, pose questions, examine word choice) 2) highlight researched information one color 3) highlight the author’s personal opinion in another. Faggot by THE DAILY DISH in The Atlantic MAR 6 2007, 12:16 PM ET I watched Ann Coulter last night in the gayest way I could. I was on a stairmaster at a gym, slack-jawed at her proud defense of calling someone a "faggot" on the same stage as presidential candidates and as an icon of today's conservative movement. The way in which Fox News and Sean Hannity and, even more repulsively, Pat Cadell, shilled for her was a new low for Fox, I think - and for what remains of decent conservatism. "We're all friends here," Hannity chuckled at the end. Yes, they were. And no faggots were on the show to defend themselves. That's fair and balanced. I'm not going to breathe more oxygen into this story except to say a couple of things that need saying. Coulter has an actual argument in self-defense and it's worth addressing. Her argument is that it was a joke and that since it was directed at a straight man, it wasn't homophobic. It was, in her words, a "school-yard taunt," directed at a straight man, meaning a "wuss" and a "sissy". Why would gays care? She is "pro-gay," after all. Apart from backing a party that wants to strip gay couples of all legal rights by amending the federal constitution, kick them out of the military where they are putting their lives on the line, put them into "reparative therapy" to "cure" them, keep it legal to fire them in many states, and refusing to include them in hate crime laws, Coulter is very pro-gay. As evidence of how pro-gay she is, check out all the gay men and women in America now defending her. Her defense, however, is that she was making a joke, not speaking a slur. Her logic suggests that the two are mutually exclusive. They're not. And when you unpack Coulter's joke, you see she does both. Her joke was that the world is so absurd that someone like Isaiah Washington is forced to go into rehab for calling someone a "faggot." She's absolutely right that this is absurd and funny and an example of p.c. insanity. She could have made a joke about that - a better one, to be sure - but a joke. But she didn't just do that. She added to the joke a slur: "John Edwards is a faggot." That's why people gasped and then laughed and clapped so heartily. I was in the room, so I felt the atmosphere personally. It was an ugly atmosphere, designed to make any gay man or woman in the room feel marginalized and despised. To put it simply, either conservatism is happy to be associated with that atmosphere, or it isn't. I think the response so far suggests that the conservative elites don't want to go there, but the base has already been there for a very long time. (That's why this affair is so revealing, because it is showing which elites want to pander to bigots, and which do not.) Coulter's defense of the slur is that it was directed at an obviously straight man and so could not be a real slur. The premise of this argument is that the word faggot is only used to describe gay men and is only effective and derogatory when used against a gay man. But it isn't. In fact, in the schoolyard she cites, theprimary targets of the f-word are straight boys or teens or men. The word "faggot" is used for two reasons: to identify and demonize a gay man; and to threaten a straight man with being reduced to the social pariah status of a gay man. Coulter chose the latter use of the slur, its most potent and common form. She knew why Edwards qualified. He's pretty, he has flowing locks, he's young-looking. He is exactly the kind of straight guy who is targeted as a "faggot" by his straight peers. This, Ms Coulter, is real social policing by speech. And that's what she was doing: trying to delegitimize and feminize a man by calling him a faggot. It happens every day. It's how insecure or bigoted straight men police their world to keep the homos out. And for the slur to work, it must logically accept the premise that gay men are weak, effeminate, wusses, sissies, and the rest. A sane gay man has two responses to this, I think. The first is that there is nothing wrong with effeminacy or effeminate gay men - and certainly nothing weak about many of them. In the plague years, I saw countless nelly sissies face HIV and AIDS with as much courage and steel as any warrior on earth. You want to meet someone with balls? Find a drag queen. The courage of many gay men every day in facing down hatred and scorn and derision to live lives of dignity and integrity is not a sign of being a wuss or somehow weak. We have as much and maybe more courage than many - because we have had to acquire it to survive. And that is especially true of gay men whose effeminacy may not make them able to pass as straight - the very people Coulter seeks to demonize. The conflation of effeminacy with weakness, and of gayness with weakness, is what Coulter calculatedly asserted. This was not a joke. It was an attack. Secondly, gay men are not all effeminate. In the last couple of weeks, we have seen a leading NBA player and a Marine come out to tell their stories. I'd like to hear Coulter tell Amaechi and Alva that they are sissies and wusses. A man in uniform who just lost a leg for his country is a sissy? The first American serviceman to be wounded in Iraq is a wuss? What Coulter did, in her callow, empty way, was to accuse John Edwards of not being a real man. To do so, she asserted that gay men are not real men either. The emasculation of men in minority groups is an ancient trope of the vilest bigotry. Why was it wrong, after all, for white men to call African-American men "boys"? Because it robbed them of the dignity of their masculinity. And that's what Coulter did last Friday to gays. She said - and conservatives applauded - that I and so many others are not men. We are men, Ann. As members of other minorities have been forced to say in the past: I am not a faggot. I am a man.