irony - difficult

advertisement

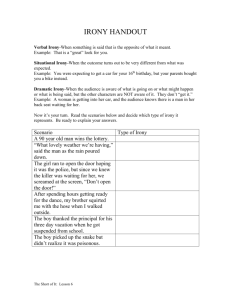

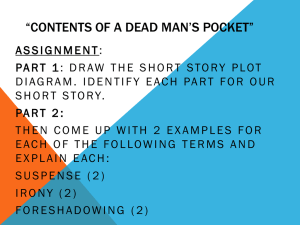

IRONY by Don L. F. Nilsen and Alleen Pace Nilsen 13 1 Irony: A Definition 13 2 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS • • • • • • • • • 1. Explain “eiron” and “irony” (3) 2. What is dramatic irony? (5) 3. Who is Chauncy Gardner? (7) 4. Explain the irony of “Being There,” “Don Juan,” “The Gift of the Magi,” “Mark Anthony’s Speech,” “A Modest Proposal,” The Rape of the Lock,” “Screwtape Letters,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “The War Prayer.” 5. Contrast linguistic and situational irony (11) 6. Contrast irony (gallows humor) and satire (10). 7. What is socratic irony (13)? 8. Contrast stable irony and observable irony (14). 9. Explain tragic irony (15). 13 3 GREEK EIRON • The word irony is related to the Greek eiron meaning “dissembler in speech.” • In modern usage it commonly refers to speech incidents in which the intended meaning of the words is contrary to their literal interpretation or to the expected meaning. • In conversations, people are often aware that they are being ironic when, for example, they want to change the subject and they begin with, “Not to change the subject, but….” • Similarly, a speaker who wants to emphasize a point he is making starts with fake humility: “Far be it from me to say, but …..” • Someone with an unproven argument might begin with, “Clearly …”, or “As is well known….” (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 168) 13 4 JOHNNY CARSON • Johnny Carson kept a toilet company from using the “Here’s Johnny” as a trademark. • They had the slogan, “The World’s Foremost Commodian.” • The judge decided in favor of Carson not because of an invasion of privacy, or because of a demeaning of the plaintiff’s reputation, but because the “Here’s Johnny” toilets might be confused with the “Here’s Johnny” clothing and restaurants. • (Nilsen & Nilsen 190) 13 5 DRAMATIC IRONY • Dramatic irony occurs when the audience members know things that the characters do not know. 13 6 • In George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara, Unterschaft asks Bilton, the foreman, if anything is wrong, and Bilton responds that a “gentleman walked into the shed and lit a cigarette, sir; that’s all.” • The stage directions are that Bilton is to say this “with ironic calm.” • The irony is obvious only when the audience learns that the shed is filled with high explosives. • (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 169) 13 7 • Jerzy Kosinski’s novel and the movie Being There. is about a mentally disabled gardener named Chauncey Gardner. • Those around him treat him as though he is a sage and a great visionary. They supply grandiose metaphorical meanings for what are the simple and sometimes inane observations of an ordinary gardener. (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 169) 13 8 HISTORY OF IRONY • The period in literary history in which irony was most developed was the Age of the Enlightenment, the time of Voltaire, Hume, Pope, Dryden, Swift, Addison, Steele, and Diderot • However, irony has been included in literature throughout history. In Chaucer’s 14th-century Canterbury Tales, an unhappily married merchant grandly praises marriage. 13 9 • In William Shakespeare’s 16th-century Julius Caesar, Marc Antony’s extravagant praise of Caesar is ironic. • Jonathan Swift’s 18th-century “Modest Proposal” that the English begin eating Irish babies was in no sense modest. • An additional irony is that some of Swift’s opponents read his ironic proposal as legitimate rather than ironic and attempted to have Swift committed as mentally ill. • (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 169) 13 10 IRONY VS. SATIRE • Critic Northrop Frye makes a distinction between satire and irony. He says that satire is a criticism of society with a clear understanding in the author’s mind of what society should be like, but is not. • The author of a satire hopes to persuade readers to work for the author’s vision as does C.S. Lewis in his Screwtape Letters. • Those who create gallows humor and irony do not intend to point their readers in a particular direction, but instead to leave them in doubt. • As Frye says, “Whenever a reader is not sure what the author’s attitude is or what his own is supposed to be, we have irony with relatively little satire” (Frye 131-239). 13 11 LINGUISTIC VS. SITUATIONAL IRONY • Many modern critics make only the two-way distinction between linguistic and situational irony. • Linguistic irony requires a sender and a receiver, while situational irony requires only an observer with a clever mind as when Lily Tomlin buys a waste basket. • The clerk puts it into a paper sack so she can take it home, and the first thing Tomlin does when she gets home is to put the paper sack into the waste basket. • Derek Evans and Dave Fulwiler’s Who’s Nobody in America is filled with such ironic complaints as the one from James M. Gatwood of San Ramon, California. In seven visits to his dentist he spent $2,800 and the dentist still calls him Sidney. Gatwood asks in frustration, “Who the hell is Sidney?” • (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 168) 13 12 • There is double irony in O. Henry’s story “The Gift of the Magi” in which a husband sells his watch to buy combs for his wife’s hair and she sells her hair to buy a gold chain for his watch. • This is similar to the joke about the two friends, one a Catholic and one a Protestant, who try to convert each other. • They present such convincing arguments that the Protestant becomes a Catholic and the Catholic becomes a Protestant. • (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 169). 13 13 !SOCRATIC IRONY • Socratic irony occurs when a person pretends to be ignorant and willing to learn from another, but then asks adroit questions that expose the weaknesses in the other person’s argument. • (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 169) 13 14 !!STABLE IRONY VS. OBSERVABLE IRONY • Literary critic Wayne Booth uses the term stable irony to refer to that which humans create to be heard or read and understood with some precision. He says that stable ironies allow readers glimpses into authors’ most private thoughts. • An example of Observable irony is when a premature monsoon ruins an army’s invasion plans or lightning strikes just as a preacher raises his arms to make a dramatic point about God. • In such situations, all that is needed is an aware observer. Writers and dramatists often work such observable ironies into their plots (Nilsen & Nilsen Encyclopedia 169). 13 15 !!!TRAGIC IRONY • Tragic irony is used for situations where there are terrible consequences, as in the Greek drama Oedipus Rex. 13 16 VISUAL IRONY 13 17 References: Attardo, Salvatore. “Irony as Relevant Inappropriateness.” Journal of Pragmatics 32 (2000): 793-826. Attardo, Salvatore. “Multimodal Markers of Irony and Sarcasm.” HUMOR: International Journal of Humor Research. 16.2 (2003): 243-260. Attardo, Salvatore. “On the Pragmatic Nature of Irony and its Rhetorical Aspects.” in Pragmatics in 2000. Ed. Eniko Nemeth, Antwerp, Belgium: International Pragmatics Association, 2001, 52-66. Barbe, Katharina. Irony in Context. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1995. Booth, Wayne. The Rhetoric of Irony. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1974. Brown, Robert L. “The Pragmatics of Verbal Irony.” in Language Use and the Uses of Language Eds. Roger W. Shuy and Anna Shnukal. 1976, 111-127. Brower, Reuben A. “Light and Bright and Sparkling: Irony and Fiction in Pride and Prejudice.” Twentieth Century Interpretations of “Pride and Prejudice.” Ed. E. Rubenstein. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969, 31-45. 13 18 Clift, Rebecca. “Irony in Conversation.” Language in Society 28.4 (1960): 491-656. Colston, H. L. “Salting a Wound or Sugaring a Pill: The Pragmatic Functions of Ironic Criticism.” Discourse Processes 23 (1997): 25-45. Coromines I Calders, Diana. “Intensification, Reduction or Preservation of Irony? Günter Grass’s “Im Krebsgang” and Its Translation into English.” in Dimensions of Humor: Exlorations in Linguistics, Literature, Cultural Studies and Translation. Ed. Carmen Valero Garcés. València, Spain: Universitat de València, 2010, 141-168. Dews, Shelly. “Muting the Meaning: A Social Function of Irony.” Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 10.1 (1995): 3-19. Falletta, Nicholas. The Paradoxicon. New York, NY: Wiley, 1983. Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ Press, 1957. 13 19 Gans, Eric. Signs of Paradox, Irony, Resentment, and Other Mimetic Structures Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997. Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr., and Christen D. Izzett. “Irony as Persuasive Communication.” in Figurative Language Comprehension: Social and Cultural Influences. Ed. Katz and Colston. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2005. Gibbs, Raymond W. Jr., and Herbert L. Colston, editors. Irony in Language and Thought: A Cognitive Science Reader. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2007. Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. “Irony in Talk among Friends.” Metaphor and Symbol 15 (2000): 5-27. Giora, R. “On Irony and Negotiation.” Discourse Processes 19 (1995): 329-264. Good, Edwin M. Irony in the Old Testament. Sheffield, England: Almond, 1981. 13 20 Graban, Tarez Samra. “Feminine Irony and the Art of Linguistic Cooperation in Anne Askew’s Sixteenth-Century Examninacyons. Rhetorica 25.4 (2007): 385-413. Gurewitch, Morton. The Ironic Temper and the Comic Imagination. Detroit, MI: Wayne State Univ Press, 1994. Handwerk, Gary J. Irony and Ethics in Narrative: From Shlegel to Lacan. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ Press, 1985. Holland, Glenn S. Divine Irony. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna Univ Press, 2004. Hutchens, Eleanor N. “The Identification of Irony.” English Language Handbook 27.4 (1960): 249-363. 13 21 Jablonski, Carol J. “Dorothy Day’s Contested Legacy: ‘Humble Irony’ as a Constraint on Memory.” Journal of Communication and Religion 23 (2000): 2949. Kaufer, David. “Irony and Rhetorical Strategy.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 10.2 (1977): 90-110. Kaufer, David. “Understanding Ironic Communication.” Journal of Pragmatics 5 (1981): 495-510. Knox, Norman. The Word Irony and Its Context, 1500-1755. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1961. Kotthoff, Helga. “An Interactional Approach to Irony Development.” Humor in Interaction. Eds. Neal R. Norrick and Delia Chiaro. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins, 2009, 49-77. Kreuz, Roger J., and Richard M. Roberts. “On Satire and Parody: The Importance of Being Ironic.” Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 8.2 (1993): 97-109. LaMarre, Heather L., Kristen D. Landreville, and Michael A. Beam. “The Irony of Satire.” International Journal of Press/Politics 14.2 (2009): 212-231. 13 22 Lang, Candace. Irony/Humor: Critical Paradigms. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988. Muecke, Douglas Colin. Irony and the Ironic. New York, NY: Methuen, 1980. Myers, Greg. “The Rhetoric of Irony in Academic Writing.” Written Communication 7.4 (1990): 419-455. Nilsen, Alleen Pace, and Don L. F. Nilsen. Encyclopedia of 20th-Century American Humor. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000. Nilsen, Don L. F., and Alleen Pace Nilsen. “Irony.” Comedy: A Geographic and Historical Guide, Volume II. Ed. Maurice Charney. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2005, 394-409. Olson, Kathryn M., and Clark D. Olson. “Beyond Strategy: A Reader-Centered Analysis of Irony’s Dual Persuasive Uses.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 91.1 (2004): 24-52. Pexman, Penny M. “It’s Fascinating Research: The Cognition of Verbal Irony.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 17.4 (2008): 286-290. 13 23 Pexman, Penny M. “Social Factors in the Interpretation of Verbal Irony: The Roles of Speaker and Listener Characteristics.” in Figurative Language Comprehension Eds. H. L. Colston and A. N. Katz. Mahway, NJ, 2005, 209-232. Purdy, Jebediah. For Common Things: Irony, Trust, and Commitment in America Today. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. Ritchie, David. “Frame-Shifting in Humor and Irony.” Metaphor and Syhmbol 20 (2005): 275-294. Sedgewick, Garnett Gladwin. Of Irony: Especially in Drama. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1948. Sperber, Dan, and Deidre Wilson. “Irony and the Use-Mention Distinction.” in Radical Pragmatics. Ed. P. Cole, New York, NY: Academic Press, 295-318; also in Pragmatics: A Reader Ed. S. Davis, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991, 550-563. 13 24 Swearingen, C. Jan. Rhetoric and Irony: Western Literacy and Western Lies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991. Swearingen, C. Jan. “The Rhetor as Eiron: Plato’s Defense of Dialogue.” PRE/TEXT 3.4 (1982). Wilson, Deirder. “The Pragmatics of Verbal Irony: Echo or Pretence?” Lingua 116 (2006): 1722-1743. Williams, Dana A. African American Humor, Irony, and Satire: Ishmael Reed, Satirically Speaking. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishinlg, 2007. Williams, Joana P. “Does Mention (or Pretense) Exhaust the Concept of Irony?” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 113.1 (1984): 127-129. Wright, Andrew H. “Irony and Fiction.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Symbolism, and Creative Imagination 12.1 (1953): 1-143. Wright, Elizabeth A. “‘Joking isn’t safe’: Fanny Fern, Irony, and Signifyin(g).” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 31.2 (2001): 91-110. 13 25