Analytical essay

advertisement

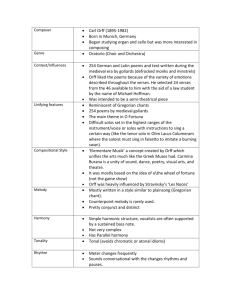

Chelsea Hudson Musicology Essay in Full Carl Orff: Born 10 July, 1895 Died 29 March, 1982 Carl Orff was a German composer from the twentieth century best known for his “Carmina Burana”. Orff was also known for his work in musical education, specifically in his study of the connections between music and movement. He found connects between the dramatic and musical elements of his compositions with their “insistent, repeated patterns of notes and compelling rhythms” (Naxos Classical Music, 2014a). From there, the “Orff Approach” was developed as a way of teaching music to children through singing, dancing and acting which engaged both the mind and the body (Estrella, 2014). Carl Orff wrote a variety of dramatic choral works and operas, but he is certainly best known for his “Carmina Burana”, a scenic cantata (Wikipedia, 2014b). Merriam-Webster (2014) states: “A cantata is a piece of music, for singers and instruments, which usually has several movements and often has a religious subject.” In more literal terms, cantata is Italian for the word ‘sung’ (Wikipedia, 2014a) and a scenic cantata is one that is ‘sacred’ or ‘secular’ and meant for stage with accompanying sets, costumes and movement (Dorricott & Allan, 1990). Among the most well-known of all cantatas, the “Carmina Burana”, written from 1935-1936, is no exception with its introductory (and concluding) movement, “O Fortuna”, used in countless films as some of the most recognisable music ever written. Based on poems from a book of thirteenth-century songs, discovered in 1803 at a monastery in southern Germany, it deals with nature, love and the ‘free life’ (Dorricott & Allan, 1990). The medieval lyrics of “O Fortuna”, specifically, complain about fate and fortune with the “personification of luck in Roman mythology” (Wikipedia, 2014g). In medieval times, fortune was likened to a turning wheel, bringing alternatively good or back luck (Dorricott & Allan, 1990) and the uncertainty of fortune was regularly used as a motif in medieval literature (Betts, 2007). Composed from 1935-36, Carl Orff was providing a bridge between impressionist and modern music in a period known as the “Post Great War Years”. This period was arguably one of the most surprising since composers ‘pulled’ in many contradicting and opposing directions (Naxos Classical Music, 2014b). This is exemplified in the fact that “O Fortuna”, written well into the twentieth century, was composed to be strongly reminiscent of the Middle Ages (around 1100s to the 1400s). Some characteristics of medieval music can be seen in the table below (Deverich, 2013; San Mateo County Community College District, n.d.): Element Description of medieval music Performance Primarily vocal, instruments used to accompany vocal lines Rhythm No regular beat, complex, syncopations Melody Small melodic intervals, sacred melodies often based on church modes Harmony Mixture of consonance and dissonance, parallel fifths and octaves Texture Monophonic texture; heavy, dense, thick sound 1 / 18 Chelsea Hudson For Carl Orff to follow these characteristics of the Middle Ages, was a very twentieth-century ‘move’ in itself. This is shown in the table below on musical characteristics of the Modern Period (Coates, 2008): Element Description of ‘modern’ music Harmony Traditional rules of harmony not followed, fifths/octaves moved freely in parallel motion, underlying harmonies often unresolved, extended chords, dissonances unprepared and unresolved Tonality Unconventional scale patterns (e.g. modes), bi-tonal, often atonal Rhythm Cross-rhythms and syncopation, sharp, very rhythmic, energised Texture Multi-layered Dynamics Often loud and confronting Themes Reflects anxieties, fears, pressures of contemporary life (in this case, complaining about fortune in medieval life) 2 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Ludwig van Beethoven: Best-known compositions: 9 symphonies 5 concertos for piano 32 piano sonatas 16 string quartets Chamber music Choral works Songs work. Realising his condition was getting increasingly worse; he threw himself into writing what turned out to be some of his greatest music – his piano sonatas. Sadly, by 1811, he stopped his public performances since he could no longer hear his own music (Prevot, The Era of Beethoven, 2013), and in 1826 he died, age 57, from a mere cold which complicated health problems that he had suffered his whole life (Davis, 2006). The exact details of Beethoven’s death, however, are one of music’s greatest mysteries with his final words and his cause of death subject to much disagreement. His official cause of death was liver failure (Mitchell, 2014) and the various autopsy findings were as listed below (Wikipedia, 2014d): Shrunken liver due to heavy alcohol consumption Born 17 December, 1770 Died 26 March, 1827 Ludwig van Beethoven was a German composer bridging the Classical and Romantic eras. He studied music under Joseph Haydn after moving to Vienna in 1792 and because one of the most famous and influential composers of all time (Wikipedia, 2014f; Prevot, The Era of Beethoven, 2013). Unfortunately, Beethoven began to lose his hearing in 1796 due to constant ringing in his ears which made it nearly impossible to It was estimated between 10,000 and 30,000 people attended Beethoven’s funeral (Prevot, Biography: Beethoven's Life, 2008; Wikipedia, 2014d). Damage to aural nerves Excess of fluid in his skull of “unusual thickness” Calcareous growths on the kidney from painkiller abuse Swollen spleen Pancreatitis Distended inner ear Liver failure As previously mentioned, Beethoven ‘threw’ himself into composing and wrote his Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor in 1798. Also known as “Sonata Pathétique”, Beethoven dedicated this piece to his friend Prince Lichnowsky who is “remembered today for his patronage of music and his relationships with Mozart and Beethoven” (Wikipedia, 2014e). Influence by his composition teacher, Haydn, the “Pathétique Sonata” shows Beethoven’s classical side while still featuring a lyrical melody-line reminiscent of the Romantic Period (Lemmon, 2009). The “Pathétique Sonata” featured three movements: 1) “Grave – Allegro di molto e con brio” 2) “Adagio cantabile” 3) “Rondo: Allegro” 3 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Since it’s considered that Beethoven really was the ‘bridge’ between the Classical and Romantic era, below is a comparison table of the typical musical characteristics (Coates, 2008): Element Classical Period Romantic Period TIME FRAME 1750-1820 1830-1920 Themes Shared with ancient Greeks Referred to the ‘golden age of values of beauty, clarity and virtuosos’ proportion Texture Concerned with balance, Contrasting moods, freedom in structure and precision; form, dramatic contrast homophonic styles; deceptively simple; ‘regular’ Dynamics Full spectrum of dynamics Wider emotional range, an even larger range of pitch and volume Performance Demands elegance and pristine Rubato considered of clarity, proportioned dynamics importance, much use of the and phrasing, observation of the pedal, predominantly legato tiniest details (i.e. phrasing and articulation), steady and controlled Tonality Modulations to closely related Richer harmonies, discords, keys wider range of notes Melody 2-note phrase Lyrical and passionate melodies; longer, sweeping melodies; often featuring chromaticism 4 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Analysis of “O Fortuna”: “O Fortuna” is the opening and closing piece of the scenic cantata, “Carmina Burana”. It’s within a section entitled, “Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi” along with a second piece “Fortuna Plango Vulnera” (Classical Net, 2014). This section is, somewhat obviously, to do with the whole concept of fortune since “O Fortuna” directly translates to “Oh Fortune” and forms a prologue to the work in which acknowledges the changeable nature of fate affecting all humans; rich or poor, strong or weak (Dorricott & Allan, 1990). The great success of Carl Orff’s composition, “O Fortuna”, is that it’s seemingly simple yet incredibly powerful. Before a detailed analysis is explored, the general concepts used to create a medieval atmosphere can be seen: WHAT WHY 3rds, 5ths and parallel A key concept of the Middle Ages is its simplicity which motion can be conveyed within simple harmony Aeolian mode Secular compositions were often based on a church mode in medieval times. Aeolian mode beginning on D is the mode also known as a ‘natural minor scale’. No raised seventh – very ‘medieval’ D E F G A Bb C D Asymmetrical Sounds ‘free’ Block harmony Create a declamatory effect Discords To show the harsh reality of life and fate. This is exemplified in the dramatic opening discord which doesn’t resolve until the final chord of the bar Dissonance Creates tension and provides drive which moves the music forward because it ‘begs’ for release Full chorus and This is a metaphor because fate affects all people and orchestra the chorus are like observers of the wheel of fortune. The full orchestra is only used for dramatic climax points… Percussion instruments are constant since Orff believed rhythm was most important. Higher/doubled range Doubled ranges or octaves make the music seem even louder when the dynamics are already at extremes (i.e. fortissimo) Homophonic “O Fortuna” is homophonic in that it has a chorus and an accompaniment – it does, however, move in two ‘layers’. The vocal layer is often monophonic and the instrumental is sometimes even polyphonic. Thus, the texture is inconstant and difficult to define. Lyrics (provide English translation) The lyrics tell of how the moon is another metaphor for fate and fortune. Like the moon ‘changes’ (waxing/waning), so does fortune – “first oppresses then soothes”. The final line of the lyrics is about everyone coming together to realise that they are all at the mercy of fortune. The lyrics translate to “everyone weep with me” and then the chorus’ final note is held for 9 bars while the orchestra plays a fast and intense passage at fortississimo (fff) right until the very end. In this case the orchestra represents the merciless power of destiny and the chorus represent the people who are slaves to 5 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Melodic contour Melodic ostinato Ostinato Pedal notes Rhythmic patterns Strophic form Structural pattern Tempo – pesante Terraced dynamics Tierce de Picardie Timpani ‘Train tracks’ Triple metre fortune. The contour of the melody is very smooth. This is due to the fact that in medieval times music notation was through neumes which didn’t really allow for extreme melodies. An example can be seen in the image below (The Schøyen Collection, 2011): Neumes were the basic musical notation used before invention of notation on a five-line staff (Wikipedia, 2014i). The lyrics speak of the “wheel of fortune” and the melodic ostinato conveys a turning motion. Ostinato in Italian means ‘stubborn’, pointing to the insistence of the continually repeating musical figure. Its stubbornness portrays the ruthless wheel of fortune. unity and brings it all together The obsessively repetitive rhythms make for a static and primitive quality in keeping with the medieval theme. The repetition is balanced by strong contrasts within the dynamics. Strophic form is where each stanza of lyrics has the same melody. This further conveys repetition and the turning motion. There is this same pattern within the whole piece (in the melody, the form, etc.) of short-short-long. An example of this is in the first section – the first and second phrases are short and the third is elongated. This continues throughout the whole piece and keeps it cohesive. Pesante means ‘heavily’ – i.e. the burden of destiny Building intensities Unexpected, fortune has power over all and is uncontrollable. It further heightens the drama Suggests power; menacing The ‘train tracks’ are formally known as ‘caesurae’ which indicates a brief, silent pause during which time is not counted. Miss Ellena Papas (2014) described the use of the caesura is to “take a breath because all hell is about to break loose”. This is true in that the intensity of the piece dramatically escalades after the caesura. Like a waltz, the triple metre also suggests a turning motion. 6 / 18 Chelsea Hudson As already stated, the full orchestra was used as a metaphor because fate affects all people. Therefore there are parts for flute, oboe, English horn, clarinets, bassoons, horn, trumpet, trombone, tuba, timpani, cymbals, full choir (SATB), piano, violins, viola, cello and contrabass. The first page the full score is shown below: The form of “O Fortuna” cannot be easily classified like ‘sonata’ form or ‘rondo’ form. It is, however, in two distinctly different parts. The first part (called ‘A’ for the purpose of this analysis) is the shorter of the two, lasting for only 4 bars. The second part (‘B’) goes for the remainder of the piece – 97 bars. For analytical reasons, this has then been broken into B1.a, B1.b, B2.a, B2.b and CODA so as to acknowledge identically repeated sub-sections. 7 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Section A Section ‘A’ goes for only 4 bars, which is extremely short in comparison to the ‘B’ section. To make up for the short duration, the time signature is in the three semibreves per bar which sounds very heavy, slow and powerful. The lyrics in the beginning are simply “o fortuna”, and to convey fortune’s power the dynamics are at fortissimo which means ‘very loudly’. It’s a bold statement right from the very start. There is also syncopation, as the first note doesn’t start on the ‘strong’ beat of the bar, and a deliberate clash in the first sound that’s heard. This creates tension and begs for release although the dissonance never actually resolves until the next section. In keeping with the short-short-long pattern, the third phrase of section ‘A’ is much longer to keep the balance and is ‘pressing on faster’, as told by poco stringendo. Section B1 The ‘B’ section is almost four times the speed of section ‘A’ as not only has it moved from three semibreves (per bar) to three minims, but the tempo has also doubled from 60 minim beats per bar to 120-136 minim beats per bar. In addition, its dynamics are very contrasting. The ‘A’ section was at fortissimo and section ‘B1’ is reduced pack to pianissimo (very softly), yet while it is very soft, each note is accented as mezzo staccato (detached) so the chorus comes across as a forceful whisper. (a) The ‘B1.a’ section goes for 16 bars of a simple melody with a range of only 3 notes (from E to G). The texture is so much more diminished than section ‘A’ and all the elements are kept relatively simplistic – the chorus is ‘chanting’ in unison; the texture is softer and lighter. The accompaniment is also extremely repetitive with a syncopated ostinato that occurs three times in two bars within the bassoon, the piano, the violin, the viola and the cello parts. This ostinato occurs 84 times in the entire ‘B1’ section. 8 / 18 Chelsea Hudson (b) ‘B1.b’ sounds relatively similar to ‘B1.a’ although there are some subtle differences – for example, it is half the length, lasting for only 8 bars. There are also added parts for flute, clarinet and contrabassoon, and the choir splits into three sections – the soprano and bass parts are the same, while the altos are a third below and the tenors are on an ‘A’ the whole time. These subtle differences create layers in the piece to slowly rebuild since it was at fortissimo in section ‘A’ and dropped right back down for section ‘B1’. (a) ‘B1.a’ then repeats and the chorus cuts back to unison which creates a ‘swelling’ effect as the piece builds and thins over and over again. The dynamics are also reinforced as sempre pp which means ‘always very soft’. (b) Then ‘B1.b’ returns as the accompaniment thickens slightly and the music swells. (b) The whole ‘B1.b’ section repeats again one last time which acts as a preparation for ‘B2’. There’s been a huge contrast in dynamics followed by a long section in pianissimo so this repeated section reinforces what has been heard so far. There is however, a minor change in the last phrase (bars 57-60), making it sound more ‘final’, which indicates something new is about to happen. Section B2 The piece starts off huge and bold but then it fades away to almost nothing, gradually building back up again. Just before the ‘B2’ section begins, there is the use of a caesura (also known as the ‘train tracks’). This is essentially like a dramatic pause before chaos and, from the ‘B2’ section until the end; it is as if “the powers of darkness have been unleashed with great force and passion” (Papas, 2014). To further increase the drama, every instrument is playing and most are on the ostinato that was first introduced in ‘B1’. This ostinato of cross-rhythms is made up of the tonic note (D), C and A. D and A are a fifth a part which leaves the harmony ‘open’ as you can’t tell whether it’s supposed to be major or minor. The added C creates dissonance that doesn’t quite resolve because when the C isn’t played in one part, it’s played in another part. This can be seen in the music for the violin and viola. 9 / 18 Chelsea Hudson (a) The ‘B2’ section brings a similar melody with an extreme change in dynamics and a thicker accompaniment. The dynamics go from pianissimo and return back up to fortissimo, while the tempo also increases to 144 minim beats per bar. The whole aim of this section is to be dramatic, loud and fierce – when the dynamics are already at extremes, octaves are used within the harmony to create an effect that sounds even louder and more ‘full’. Within the harmony, certain parts hold ‘pedal notes’, like the contrabassoon, trombone, tuba and contrabass parts. At the same time, the string instruments copy the chorus as they sing with a dramatically enlarged range and accented notes. This texture is quite homophonic in that it has a definite chorus and accompaniment. Finally, the word martellatissimo is introduced within the piano accompaniment. This word means ‘heavily hammered’ although it is not often used. If the word is broken up, the first part is ‘martel’, in English, means a hammer-like weapon (Dictionary.com, 2014) and the second part is a commonly used suffix, ‘issimo’, meaning ‘extremely’ or ‘remarkably’. (b) ‘B2.b’ is a lot like ‘B2.a’… the only difference is that the accompaniment is expanded into thirds in some places (adding interest). Thirds are introduced within the horn, soprano, tenor, viola and cello parts. The cymbals are also played much more frequently adding further tension and drama. Lastly, the melody sung by the chorus is suddenly in smooth thirds. This is extremely contrasting since everything preceding it has been harsh and striking – a reason for its smoothness is that it demonstrates the smooth and calm side of fate before jumping back to a completely extreme coda. This is like a metaphor for the calm before the storm. CODA Finally, just as it seems as though “O Fortuna” has reached its peak, the coda is added so that it goes out on a ‘bang’. Here, the tempo increases, there is a crescendo to fff (fortississimo) and there’s a tierce de Picardie with the addition of the F sharp within the accompaniment. A tierce de Picardie is when a major chord is used at the end of a piece in a minor key and portrays the contrast and duality of life. On one hand it’s ‘good’ in the major-sounding harmony and the long held notes of the chorus. In comparison, the busy accompaniment and the dissonance of the C natural create an ‘evil’ side. When these two are played at the same time it demonstrates the how uncontrollable and unpredictable the nature of fortune is. 10 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Analysis of “Adagio Cantabile”: “Adagio Cantabile” is the second movement of Beethoven’s “Sonata Pathétique”, formally known as his Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13. When the piece was written, the word ‘pathetic’ did not convey pity or misery, rather it meant ‘emotional’ and in some cases ‘heartbreaking’. The title also mentions ‘sonata’ – the first movement of a sonata is typically in sonata form (Exposition, Development and Recapitulation); however, “Adagio Cantabile” is the second movement so it is in ‘rondo’ form. The word ‘sonata’ comes from the Italian verb ‘sonare’, meaning ‘to sound’, and is a solo instrumental piece in several movements (in this case there’s three) (Coates, 2008). Before a detailed analysis is explored, the general concepts used to create this Classical ‘perfection’ can be seen: WHAT WHY A flat major Beethoven’s signature key was C minor because he felt this key to be “powerful and emotionally stormy” (Wikipedia, 2014f; Wikipedia, 2014h). “Adagio Cantabile” is in A flat major which is the subdominant relative major of C minor. Adagio cantabile Added note chords Contrary motion Dotted notes Homophony Proportional Rondo form Simple duple Simplicity Adagio cantabile is a tempo meaning ‘slowly, in a singing style’. Typical of a slow movement, Beethoven follows compositional rules of the Classical era while featuring the lyrical melody of the Romantic era. Added note chords and inversion within the harmony add ‘colour’ and richness of tone underlying a seemingly simple composition. Added notes also create interest in repetitive chordal patterns. Creates balance; seen as perfection in the Classical Period Hovering; lingering Emphasising a single melody line (melody with accompaniment), characteristic of the Classical Period The perfect proportions of Beethoven’s composition seem to suspend time giving it a warm and spacious aura Sections ABACA + Coda… perfectly and neatly structured exemplifying Classical values. The main theme ‘A’ sounds at least three times, separated by two different and contrasting sections. Simple duple means two crotchet beats in a bar. As the name suggests, this is a ‘simple’ time signature which fits in with the Classical era of its composition. It allows for the 2bar phrases and 2-note phrases that were so popular at that time. Beethoven did not add anything ‘extra’ within the “Adagio Cantabile”. This is like how less is ‘more’ and gives an exquisite sound without unnecessary nonsense. 11 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Section A Section ‘A’ begins piano (softly) in A flat major with the smoothly-contoured melody written in the bass clef. This is perfect in its simplicity – it starts off small so that there’s room to grow later on. The dominant note of E flat is repeated which opens up the harmony, making the listener unsure if it’s major or minor. This creates a ‘question’ which begs to be answered. In the same way, the tonic note isn’t used in the melody until the end of the section. The avoided tonic highlights the emotion and even just before the tonic is to be played there is a suspension where both notes on either side are held. This all serves to intensify the tension so that when the tonic is finally heard it is even more beautifully resolved. The semiquavers within the harmony create safety and comfort within the mood. The bass notes are in crotchets until the quavers in bar 3 which drive the music forward. In true classical form, the harmony begins on chord I, hovers around the dominant chord in bar 4 and finishes with a perfect cadence. The bass is also in contrary motion with the melody, exemplifying ideal counterpoint in ‘ultimate’ composition. At the end of bar 8, there are two triplets which are accented with staccatos. This is contrasting and gives a glimpse of what’s to come later on in the piece (i.e. section ‘C’). Section A1 ‘A1’ is much like the original ‘A’ section except it’s slightly fuller with the addition of harmony under the melody in the treble clef. This is new and confirming, moving in contrary motion so it sounds reassuring. To keep interest the melody is now an octave higher in the treble clef – this allows more room for harmony and sounds more complete while maintaining a soft pitch. The arpeggios in bars 12 and 13 are a gentle reminder that something is going to change – arpeggios are a form of scale and section ‘B’ introduces quite a scalic melody. The pause at the end of bar 16 is a warning that a new section is about to begin. Section B Section ‘B’ is the first ‘new’ section and thus goes for a little bit longer – 12 bars instead of the usual 8. ‘B’ starts off with a modulation to the relative minor which is F minor. The melody uses clever repetition (bars 17-19) where it is repeated three times while the C simply jumps up and down an octave. The texture, however, feels shallower as the harmony turns into block chords without a bass line. This effectively 12 / 18 Chelsea Hudson cuts the piece back so it can rebuild. As the tension increases the block chords get higher and higher until they’re sitting within the treble clef. At the end of bar 20 there is a second modulation to E flat major with the help of the B natural within the bar. E flat major is the dominant of A flat major and allows for the transition to be smoother when it does return to the ‘A’ section. In bar 24, the bass line returns, which adds comfort to a previously foreign section, it also signals that the theme will reappearance soon which it does with the modulation back to A flat major in bars 27-29. This transition is drawn out with the use of chromaticism in the melody adding tension and ‘drive’. This tension is increased with crescendos until the ‘A’ section returns at a tender pianissimo. Section A After a tension-filled ‘B’ section, the ‘A’ section plays at piano (softly). There was a lot of suspense for its return and the soft dynamics bring further attention to the beautiful, lyrical melody. This ‘A’ section is identical to the original ‘A’ section except for some minor changes such as the exclusion of the triplets that were in the original section ‘A’. Section C Section ‘C’ is again longer than both the ‘A’ and the ‘B’ sections for further contrast. This section features the triplets that were hinted at in bar 8 of “Adagio Cantabile”. From this section and onwards, the rest of the piece is in triplets, adding contrast and interest to the repeated ‘A’ sections. This section also utilises the 2-note phrase characteristic of the Classical Period (e.g. bars 38, 40 and 46). The ‘C’ section also brings a modulation to the relative minor of A flat minor. This closely related key clashes since it is so similar yet obviously minor. Almost wearily, this contrasting section comes in at pianissimo to gently change the subject. There are also chromatic countermelodies explored in bars 38, 40 and 46. Countermelodies have not been present in the piece so far, thus they add balance and interest. This section is also full of block harmonies which are strong and more powerful than the serene simplicity of the ‘A’ sections. With a crescendo, the piece further modulates to E major in bar 42. This comes across quite suddenly and is emphasised with sforzando (a strong accent) markings. More contrast is heard with the major second chords (including an added seventh) in bar 43. Second chords are typically minor yet Beethoven has composed with a major second chord to add drama. After a modulation to E major there is a point of rest at bar 44 and then continues on at pianissimo with a thinned texture. This is surprising and drives the piece forward because of its contrast. 13 / 18 Chelsea Hudson To conclude section ‘C’, arpeggios are seen in the bass (bars 48-50) and then the piece modulates back to the main key of A flat major. The chords in these bars are particularly strange to try and classify since it is modulating for a major chord to another major chord that is unrelated. To emphasise this tension, Beethoven used rinforzando (reinforcing the tone) markings to confirm what is heard. Section A2 After a wildly complex section ‘C’, the ‘A2’ is a welcome change. It is very, very similar to the original ‘A’ section except for the obvious triplets. This is now the third time the theme has repeated; therefore the triplets keep the piece moving. Section A3 ‘A3’ repeats ‘A2’ quite like how ‘A1’ repeated the main ‘A’ theme at the beginning. It’s much like its preceding section except the harmony is doubled within the counterpoint and the melody is played an octave higher. Since it is the final ‘A’ section to be heard, this reaffirms what is already known about the piece while still including subtle changes. Beethoven’s technique in effectively using repetition shows how his composition of the “Pathétique Sonata” is truly beautiful. He should his expertise in repeating his good ideas while ensuring the piece always moves in such an exquisitely-crafted manner. CODA The coda uses ornamentations like the turn in bar 68 and rinforzando markings to add interest. Beethoven also employs clever repetitions (e.g. bars 67 and 69) and sequences (bars 70-71). These techniques confirm comfort, safety and warmth. To finish off a beautiful piece, the coda is used to ensure finality after already hearing multiple repetitions of the ‘A’ sections. It’s almost another contrasting section with its block harmonies and ornamentations (such as the acciaccaturas and the turns) but the piece is superbly finished at pianissimo with its perfect cadences and its repeated tonic chord at the end (with the added fermata/pause). This highlights a loving and lingering mood while subtly emphasising the stunning serenity of the piece, “Adagio Cantabile”. 14 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Compare and Contrast: Music is powerful medium to for listeners to seek feelings such as comfort and for composers to tell their story – may it be bold or beautiful. An example of a bold piece is the well-known “O Fortuna” (from “Carmina Burana”) by composer Carl Orff. In comparison, there are many exquisitely beautiful pieces such as “Adagio Cantabile” (the second movement from Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13). To compare these pieces, we must look to the elements of music… Duration “O Fortuna” is a brilliantly powerful piece with a strong defined pulse given by the timpani. Unlike “Adagio Cantabile”, it changes time signature from three semibreves to three minims per bar. It is also heavily syncopated, heavily accented and very rhythmic since Orff valued rhythm above all else. On the other hand, “Adagio Cantabile” is soft and gentle. It has a time signature of simple duple (two crotchet beats per bar), isn’t really syncopated and accents are used sparingly. Like “O Fortuna”, the rhythm is clear and concise which was characteristic of ‘perfect’ proportion in performance of Classical-style music. Expressive Devices Dynamics and contrast were most obvious expressive devices in both pieces. While “O Fortuna” jumped from one extreme to the next, “Adagio Cantabile” was mainly played very softly and tenderly with crescendos, sforzandos and rinforzandos used, only occasionally, for added interest. In terms of contrast, “O Fortuna” was well constructed with a bold statement to start off with before completely dropping off and rebuilding again; always extreme. “Adagio Cantabile” was more predictable in this respect with more subtle contrasts. Pitch The melody in “O Fortuna” was very smooth with small ranges within the phrase. Both pieces, however, had very repetitive melodies although very cleverly composed with a constant interest and ‘drive’. The harmony was always extremely repetitive and quite simple in “O Fortuna”. Although it was modal and very dissonant, there was not much harmonic change other than the unexpected, yet effective, tierce de Picardie. In comparison, “Adagio Cantabile” had multiple modulations and was perfectly balanced with chord progressions and countermelodies as was expected in the Classical Period. Structure In terms of structure, “O Fortuna” had a very simple strophic form with two main contrasting sections and a coda (like “Adagio Cantabile”). In saying that, it could be argued that almost the whole piece was a chant in that it was incredibly repetitive with its ostinatos. On the other hand, “Adagio Cantabile” was structure in a perfect rondo form with a coda. The clever repetition and sequences were influenced by Haydn’s teaching of Classical composition and the treatment of thematic material was evidently characteristic of the era. Texture “O Fortuna” had an incredible dense texture particularly at its start and finish. It utilised a full chorus and full orchestra because its complaint about fortune affects all people. In saying this, it had great contrast when in thinned and had to gradually rebuild up to a full texture. “O Fortuna” could be defined as homophonic but is hard to classify in this respect because it is sometimes monophonic within the chorus and polyphonic within the accompaniment. In contrast, “Adagio Cantabile” is clearly homophonic with its defined melody and accompaniment. 15 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Mood The mood of “O Fortuna” could be described as dramatic, bold, forceful, intense, and grounded (because of its natural minor tonality). It could also be described as ‘primitive’ as Carl Orff intended for it to be reminiscent of the Middle Ages. His inspiration was due to the fact that the lyrics he used were from a medieval set of poems. On the contrary, “Adagio Cantabile” could only be described as beautiful, loving, lingering, calm, serene and proportional. These were ideals valued by Classical composers at the time. … While both pieces are so blatantly different they do have multiple similarities – for example, they both have suspenseful moods. “O Fortuna” is written for a chorus and thus has lyrics, yet “Adagio Cantabile” is also undeniably lyrical even without the spoken word. They both can be seemingly simple pieces, yet also incredibly powerful. This is the beauty of music. 16 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Bibliography Acres, J. (2007). "O' Fortuna!". Retrieved May 27, 2014, from http://www.acres4.com/articles/ofortuna Betts, G. (2007). Carmina Burana. Retrieved May 18, 2014, from http://www.tylatin.org/extras/cb1.html Classical Net. (2014). Carl Orff - Carmina Burana Lyrics. Retrieved May 24, 2014, from http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/works/orff-cb/carmlyr.php Coates, S. (2008). How to BLITZ! General Knowledge. Maroubra, New South Wales, Australia: A & S Coates Pty Ltd. Retrieved May 25, 2014 Davis, L. (2006). Beethoven Died from Lead Poisoning. Retrieved May 19, 2014, from http://learningenglish.voanews.com/content/a-23-2006-01-03-voa3-83127552/125325.html Deverich, R. K. (2013). Medieval Musical Style Characteristics. Retrieved June 11, 2014, from http://www.violaonline.com/unit1_3.html Dictionary.com. (2014). Martel - Definition. Retrieved June 12, 2014, from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/martial?s=t Dorricott, I. J., & Allan, B. C. (1990). In Tune With Music (Vol. 3). Roseville, New South Wales: McGraw-Hill Book Company Australia Pty Limited. Retrieved May 9, 2014 Estrella, E. (2014). Profile of Carl Orff. Retrieved May 18, 2014, from http://musiced.about.com/od/famousmusicians1/p/carlorff.htm Fuller, R. (2010). Romantic Music. Retrieved May 24, 2014, from http://www.rpfuller.com/gcse/music/romantic.html Lemmon, E. (2009). A Formal Analysis of Beethoven's Pathetique. Retrieved May 21, 2014, from http://opensourcemusic.org/?p=748 Merriam-Webster. (2014). Cantata - Definition. Retrieved May 16, 2014, from http://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/cantata Mitchell, S. (2014). How Did Beethoven Die? Music's Great Mystery. Retrieved May 25, 2014, from http://www.favorite-classical-composers.com/how-did-beethoven-die.html Naxos Classical Music. (2014a). Carl Orff. Retrieved May 18, 2014, from http://www.naxos.com/person/Carl_Orff/25615.htm Naxos Classical Music. (2014b). History of Classical Music. Retrieved May 18, 2014, from http://www.naxos.com/education/brief_history.asp Papas, E. (2014, May 5). The Use of Caesurae. (C. Hudson, Interviewer) Prevot, D. (2008). Biography: Beethoven's Life. Retrieved May 19, 2014, from http://www.lvbeethoven.com/Bio/BiographyLudwig.html 17 / 18 Chelsea Hudson Prevot, D. (2013). The Era of Beethoven. Retrieved May 25, 2014, from http://www.lvbeethoven.com/VotreLVB/erabeethoven.htmlhttp://www.lvbeethoven.com/VotreLVB/era-beethoven.html San Mateo County Community College District. (n.d.). Medieval Period. Retrieved June 11, 2014, from http://www.smccd.net/accounts/navarij/music202/s05studyaid_middleages.pdf Shannon, L. (2000). Classical Period. Retrieved May 24, 2014, from http://www.musicatschool.co.uk/year_9/Classical_sheets/Classical.PDF Tengstrand, P. (2011). Op. 13 "Pathetique". Retrieved May 27, 2014, from http://worldofbeethoven.com/op-13-pathetique-part-one-new/ The Schøyen Collection. (2011). Toscana Neumes. Retrieved June 12, 2014, from http://www.schoyencollection.com/music2.html Wikipedia. (2014a). Cantata. Retrieved May 16, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantata Wikipedia. (2014b). Carl Orff. Retrieved May 16, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Orff Wikipedia. (2014c). Carmina Burana (Orff). Retrieved May 18, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmina_Burana_(Orff) Wikipedia. (2014d). Death of Ludwig van Beethoven. Retrieved May 25, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_Ludwig_van_Beethoven Wikipedia. (2014e). Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky. Retrieved May 19, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Alois,_Prince_Lichnowsky Wikipedia. (2014f). Ludwig van Beethoven. Retrieved May 19, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_van_Beethoven Wikipedia. (2014g). O Fortuna. Retrieved May 18, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O_Fortuna Wikipedia. (2014h). Piano Sonata No. 8 (Beethoven). Retrieved May 21, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_Sonata_No._8_(Beethoven) Wikipedia. (2014i). Neumes. Retrieved June 12, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neume 18 / 18