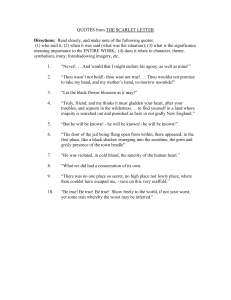

03 Figurative Language

advertisement

Figurative Language The Language of Literature Figurative language • Language which uses figures of speech; for example, metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, simile, alliteration, hyperbole, etc. • Figurative language must be distinguished from literal language. Literal language Language use that takes the meaning of words in their primary and non-figurative sense, as in literal interpretation. Literal / Literary Literary = of, relating to, or having the characteristics of letters, humane learning, or literature Literal = adhering to fact or to the ordinary construction or primary meaning of a term of expression From the Merriam-Webster Dictionary Literal / Figurative • It’s heavily raining / pouring with rain / the rain is pouring • It is raining cats and dogs / the rain is coming down in buckets • You’re a pretty sight = You look awful • You’ve got slightly wet, didn’t you? = You’ve got drenched with rain Speaking figuratively • • • • you say less than what you mean or more than what you mean or the opposite of what you mean or something other than what you mean Figurative speech Broadly defined: Any way of saying something other than the ordinary (literal) way. (From the antiquity on rhetoricians have defined over 250 separate figures.) Narrowly defined: A way of saying one thing and meaning another. Language that cannot be taken literally. Literary texts A work of literature is always a coded text, in parts it may use figurative language (figures of speech or tropes), and as a whole it always communicates ideas different from its literal meaning. Therefore the student of literature must learn the various techniques of decoding literary texts. Thomas Hardy and Emma Lavinia Gifford Thomas Hardy The Walk You did not walk with me Of late to the hill-top tree By the gated ways, As in earlier days; You were weak and lame, So you never came, And I went alone, and I did not mind, Not thinking of you as left behind. Hardy cont. I walked up there to-day Just in the former way; Surveyed around The familiar ground By myself again: What difference, then? Only that underlying sense Of the look of a room on returning thence. William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) W. B. Yeats Down by the Salley Gardens Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet; She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet. She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree; But I, being young and foolish, with her would not agree. In a field by the river my love and I did stand, And on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand. She bid me take life easy, as the grass grows on the weirs; But I was young and foolish, and now am full of tears. A willow (salley) tree Another one Robert Frost (1874-1963) American poet with an axe on his shoulder Robert Frost Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year. Frost cont. He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound's the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake. The woods are lovely, dark and deep. But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep. Two manuscripts of the poem Imagery Representation through language of sense experience Image - visual imagery (mental image) - auditory imagery (sound) - olfactory imagery (smell) - gustatory imagery (taste) - tactile imagery (touch) - organic imagery (internal sensation, hunger, fatigue) - kinesthetic imagery (movement, tension in the muscles) A figure of speech An expression extending language beyond its literal meaning, either pictorially through metaphor, simile, allusion, personification, and the like, or rhetorically through repetition, balance, antithesis and the like. A figure of speech is also called a trope. The Harper Handbook to Literature, ed. by Northrop Frye, Sheridan Baker, George Perkins. New York: Harper & Row, 1984 Figures of speech / Tropes Figures of speech = tropes Trope (Greek ‘turn’) denotes any rhetorical or figurative device Figurative language Metaphor (Greek 'to transfer') /'mɛtəfɔr, -fər/ How to spot metaphor: textual and contextual signals Metaphor and simile /'sɪməli/ in poetry: figurative language with a purpose The effects of metaphor: denotation /connotation denotation = what is referred to connotation = associations, connecting images, ideas, moods, etc. IPA transcriptions: http://dictionary.reference.com Audio: http://howjsay.com Metaphor and simile The analysis of metaphor: tenor (the concept, idea, new element) vehicle (the image to illuminate the tenor) grounds (the basis of comparison: their similarity) “O Rose, thou art sick.” (Blake) No sign of comparison: vehicle stands for tenor Simile:“O my luve's like a red, red rose” (Burns) luve=tenor red, red rose=vehicle like=grammatical indicator of similarity Figures of speech: metaphor, simile Used as means of comparing things that are essentially unlike Metaphor – the comparison is implied, implicit, i.e. the figurative term is substituted for or identified with the literal term Simile – the comparison is expressed, explicit (like, as) Metaphor A figure of speech in which one thing is described in terms of another. I. A. Richards (1893-1979), English literary critic, by 'tenor‘ meant the purport or general drift of thought regarding the subject of a metaphor; by 'vehicle' the image which embodies the tenor. Types of metaphor I A dead metaphor (cliché) is one in which the sense of a transferred image is absent. Example: "to grasp a concept" uses physical action as a metaphor for understanding. Dead metaphors normally go unnoticed. Carol Ann Duffy (1955) Sit at Peace (excerpt) When they gave you them to shell and you sat on the back-doorstep, opening the small green envelopes with your thumb, minding the queues of peas, you were sitting at peace. Sit at peace, sit at peace, all summer. […] Nip was a dog. Fluff was a cat. They sat at peace on a coloured-in mat, so why couldn’t you? […] But the day you fell from the Parachute Tree, they came from nowhere running, carried you in to a quiet room you were glad of. A long silent afternoon, dreamlike. A voice saying peace, sit at peace, sit at peace. Carol Ann Duffy Mrs Lazarus (excerpts) I had grieved. I had wept for a night and a day over my loss, ripped the cloth I was married in from my breasts, howled, shrieked, clawed at the burial stones until my hands bled, retched his name over and over again, dead, dead. (Also: allusion to John 11,1-46) Types of metaphor II An extended metaphor (conceit, concetto) establishes a principal subject (comparison) and subsidiary subjects (comparisons). Used extensively by English metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century. John Donne (1572-1631) A Valediction: Of Weeping (excerpt) Let me pour forth My tears before thy face, whilst I stay here, For thy face coins them, and thy stamp they bear, And by this mintage they are something worth. For thus they be Pregnant of thee ; Fruits of much grief they are, emblems of more; When a tear falls, that thou fall'st which it bore; So thou and I are nothing then, when on a divers shore. Types of metaphor III A mixed metaphor (catachresis) is one that leaps from one identification to a second identification inconsistent with the first. It can be deliberate or unintentional. Example: To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them? (Shakespeare: Hamlet, Act III, Scene I) Further figures of speech Synaesthesia /sɪni:s’θi:zɪə/ – the mixing of sensations, the concurrent appeal to more than one sense (e.g. hearing a colour, seeing a smell) Personification – give the attributes of a human being to an animal, an object or a concept Metonymy /mɪ’tɒnəmi/ – the use of something closely related for the thing actually meant Synecdoche /sɪ’nɛkdəki/ – the use of the part for the whole Metonymy / Synecdoche Metonymy = “substitute naming” – an associated idea names the item: “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Synecdoche – a part stands for the whole or the whole for a part: “Listen, you've got to come take a look at my new set of wheels.” (One refers to a vehicle in terms of some of its parts, "wheels“.) Even further figures of speech Symbol – something that means more than what it is Allegory – a narrative or description that has a second meaning, with more emphasis on the ulterior meaning than on the surface story Unlike metaphors, it involves a system of related correspondences. Unlike symbols, it puts less emphasis on the images for their own sake Allegory / Symbol A narrative that serves as an extended metaphor. Allegories are written in the form of fables, parables, poems, stories, and almost any other style or genre. The main purpose of an allegory is to tell a story that has characters, a setting, as well as other types of symbols, that have both literal and figurative meanings. The difference between an allegory and a symbol is that an allegory is a complete narrative that conveys abstract ideas to get a point across, while a symbol is a representation of an idea or concept that can have a different meaning throughout a literary work. Examples of allegory Plato’s Cave allegory (The Republic, Book VII) Aesop’s Fables Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene George Orwell’s Animal Farm Plato’s Allegory of the Cave The Allegory of the Cave can be found in Book VII of Plato's The Republic. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave In the allegory, Plato likens people untutored in the Theory of Forms to prisoners chained in a cave, unable to turn their heads. All they can see is the wall of the cave. Behind them burns a fire. Between the fire and the prisoners there is a parapet, along which puppeteers can walk. The puppeteers, who are behind the prisoners, hold up puppets that cast shadows on the wall of the cave. The prisoners are unable to see these puppets, the real objects, that pass behind them. What the prisoners see and hear are shadows and echoes cast by objects that they do not see. An illustration of Plato’s Cave from Great Dialogues of Plato (Warmington and Rouse, eds.) New York, Signet Classics: 1999. p. 316. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave Such prisoners would mistake appearance for reality. They would think the things they see on the wall (the shadows) were real; they would know nothing of the real causes of the shadows. Source: http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/cave. htm George Herbert (1593-1633) Redemption Having been tenant long to a rich Lord, Not thriving, I resolved to be bold, And make a suit unto him, to afford A new small-rented lease, and cancell th’ old. In heaven at his manour I him sought: They told me there, that he was lately gone About some land, which he had dearly bought Long since on earth, to take possession. Herbert cont. I straight return’d, and knowing his great birth Sought him accordingly in great resorts; In cities, theatres, gardens, parks, and courts: At length I heard a ragged noise and mirth Of theeves and murderers: there I him espied, Who straight, Your suit is granted, said, and died. Allegorical figures in Thomas Gray’s (1716-1771) Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (excerpt) Let not Ambition mock their useful toil, Their homely joys, and destiny obscure; Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile The short and simple annals of the Poor. The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power, And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave, Awaits alike th' inevitable hour:The paths of glory lead but to the grave. Gray cont. Nor you, ye Proud, impute to these the fault If Memory o'er their tomb no trophies raise, Where through the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault The pealing anthem swells the note of praise. Can storied urn or animated bust Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath? Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust, Or Flattery soothe the dull cold ear of Death? The portrait of Thomas Gray by John Giles Eccart (1747-1748) Gray’s Monument Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire St Giles Church, Stoke Poges Churchyard, Stoke Poges Southwell Minster Carvings in the Chapter House of Southwell Minster Carving in the Chapter House Statues in Salisbury Cathedral Figures of speech easy to confuse Image, metaphor, and symbol are sometimes difficult to distinguish. An image means only what it is. A metaphor means something other than what it is. A symbol means what it is and something more, too. It functions literally and figuratively at the same time. Rhetorical figures • • • • • • • simple repetition /'rɛpɪ'tɪʃən/ parallelism /'pærəlɛˌlɪzəm, -lə'lɪz-/ antithesis /æn'tɪθəsɪs/ climax /'klaɪmæks/ hyperbole /haɪ'pɜ:rbəli/ apostrophe /ə'pɒstrəfi/ irony /'aɪrəni, 'aɪər-/ Find examples for each in the quotation from Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Man (1732-1734): Cease then, nor Order imperfection name: Our proper bliss depends on what we blame Know thy own point: this kind, this due degree Of blindness, weakness, Heaven bestows on thee. Submit. - In this, or any other sphere, Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear: Safe in the hand of one disposing Power, Or in the natal, or the mortal hour. All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see; All discord, harmony not understood; All partial evil, universal good: And, spite of pride, in erring reason's spite, One truth is clear, WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT. Repetition All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see; All discord, harmony not understood; All partial evil, universal good: Parallelism A matter of grammar and rhetoric: the writer expresses in parallel grammatical form equivalent elements of content – framing words, sentences, and paragraphs to give parallel weight to parallel thoughts: “All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see; All discord, harmony not understood; All partial evil, universal good” Antithesis • a direct contrast or opposition • a rhetorical figure sharply contrasting ideas in balanced parallel structure “Cease then, nor Order imperfection name” “Safe in the hand of one disposing Power, Or in the natal, or the mortal hour.” (and lots more in the text) Climax • A point of high emotional intensity, a turning point or crisis. • The high point of an argument, reached by arranging ideas in the order of least to most importance • The point of greatest interest in any piece of writing • Repeating the same sound or word Climax after all the repetition, parallelism, antitheses: “One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right.” Hyperbole Overstatement, to make a point, either direct or ironical: “Our proper bliss depends on what we blame Know thy own point: this kind, this due degree Of blindness, weakness, Heaven bestows on thee. Submit. - In this, or any other sphere, Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear: Safe in the hand of one disposing Power, Or in the natal, or the mortal hour.” (and the rest of the excerpt as well) Apostrophe An address to an imaginary or absent person (or as if the person were absent), a thing or a personified abstraction: “Cease then, nor Order imperfection name” “Know thy own point: this kind, this due degree Of blindness, weakness, Heaven bestows on thee. Submit. - In this, or any other sphere, Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear” “All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see” Further rhetorical figures Paradox – an apparent contradiction that is nevertheless somehow true Hyperbole (overstatement) – exaggeration, adding emphasis to what is really meant Understatement – saying less than what is meant Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) Paradox Emily Dickinson: 1732 My life closed twice before its close It yet remains to see If Immortality unveil A third event to me So huge, so hopeless to conceive As these that twice befell. Parting is all we know of heaven, And all we need of hell. The manuscript of a poem by Emily Dickinson Paradox John Donne: The Legacy (excerpt) When last I died (and, dear, I die As often as from thee I go), Though it be but an hour ago, And lovers' hours be full eternity, I can remember yet, that I Something did say, and something did bestow; Though I be dead, which sent me, I should be Mine own executor and legacy. Two portraits of John Donne (1572-1631) Irony a trope, a non-literal use of language like metaphor, metonymy, etc, also can be conceived as a rhetorical figure • a type of tone, a particular way of speaking/writing, a matter of style, • can be widespread in text (unlike metaphors which are usually discrete parts of text) Irony • ironic meaning WE have to construct • DIFFERENCE between apparent meaning and true meaning • the text as a whole or a large part of it is unreliable if taken literally • an implied (vs explicit) interpretation is true Example: difference between text and situation: “WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT.” – when all sorts of things go wrong Mechanisms and techniques of irony • overemphasis of inverted meaning: Yes! I'd really like that! • internal inconsistency - in narrative: narrator is shown not to have seen the truth - in style: unexpected change in register unexpected change of rhythm unexpected alliteration rhyme fails to appear Effects of irony Irony which destabilizes: • where the intended meaning is difficult to pinpoint • internally inconsistent text • literal meaning is insufficient • no specific, authoritative or unified worldview – a final, implied meaning remains elusive Types of irony Verbal irony – saying the opposite of what is meant Dramatic irony – discrepancy between what the speaker says and what the author means Irony of situation – discrepancy between the actual circumstances and those that would seem appropriate or discrepancy between what one anticipates and what actually comes to pass William Blake: The Chimney Sweeper When my mother died I was very young, And my father sold me while yet my tongue Could scarcely cry 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep. There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head, That curled like a lamb's back, was shaved: so I said, "Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head's bare, You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair." And so he was quiet; and that very night, As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight, That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack, Were all of them locked up in coffins of black. Blake cont. And by came an angel who had a bright key, And he opened the coffins and set them all free; Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run, And wash in a river, and shine in the sun. Then naked and white, all their bags left behind, They rise upon clouds and sport in the wind; And the angel told Tom, if he'd be a good boy, He'd have God for his father, and never want joy. And so Tom awoke; and we rose in the dark, And got with our bags and our brushes to work. Though the morning was cold, Tom was happy and warm; So if all do their duty they need not fear harm. The Portrait of William Blake (1757-1827) by Thomas Phillips William Blake: The Chimney Sweeper from Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience Situational irony “The Gift of the Magi “(1906) is a short story written by O’Henry (William Sydney Porter, 1862-1910) about a young married couple and how they deal with the challenge of buying secret Christmas gifts for each other with very little money. The plot and its "twist ending" are well-known, and the ending is generally considered an example of situational irony. The photo of O’Henry and the cover of the illustrated edition of “The Gift of the Magi” O’Henry, “The Gift of the Magi” Plot Young married couple Della and James "Jim" Dillingham Young are very much in love with each other but can barely afford their one-room apartment due to their very bad economic situation. For Christmas, Della decides to buy Jim a chain for his prized pocket watch given to him by his father's father. To raise the funds, she has her long, beautiful hair cut off and sold to make a wig. Meanwhile, Jim decides to sell his watch to buy Della a beautiful set of combs made out of tortoiseshell and jewels for her lovely, knee-length brown hair. Although each is disappointed to find the gift they chose rendered useless, each is pleased with the gift that they received, because it represents their love for one another. O’Henry, “The Gift of the Magi” The story ends with the narrator comparing the pair's mutually sacrificial gifts of love with those of the Biblical Magi: “The magi, as you know, were wise men – wonderfully wise men – who brought gifts to the new-born Babe in the manger. They invented the art of giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And here I have lamely related to you the uneventful chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.” (Based on Wikipedia) Robert Frost Fire and Ice (1920) Some say the world will end in fire; Some say in ice. From what I've tasted of desire I hold with those who favor fire. But if it had to perish twice, I think I know enough of hate To say that for destruction ice Is also great And would suffice. Robert Frost: Fire and Ice Background It discusses the end of the world, likening the elemental force of fire with the emotion of desire, and ice with hate. According to one of Frost's biographers, Fire and Ice was inspired by a passage in Canto 32 of Dante’s Inferno, in which the worst offenders of hell, the traitors, are submerged, while in a fiery hell, up to their necks in ice: "a lake so bound with ice, It did not look like water, but like a glass ... right clear I saw, where sinners are preserved in ice." Robert Frost: Fire and Ice Background In an anecdote he recounted in 1960 in a "Science and the Arts" presentation, prominent astronomer Harlow Shapley claims to have inspired "Fire and Ice". Shapley describes an encounter he had with Robert Frost a year before the poem was published in which Frost, noting that Shapley was the astronomer of his day, asks him how the world will end. Shapley responded that either the sun will explode and incinerate the Earth, or the Earth will somehow escape this fate only to end up slowly freezing in deep space. Shapley was surprised at seeing "Fire and Ice" in print a year later, and referred to it as an example of how science can influence the creation of art, or clarify its meaning. Frost’s Fire and Ice // Dante’s Inferno Comparison The nine lines of Frost’s poem // the nine rings of Dante’s Hell The narrowing of the poem // the downward funnel of the rings of Hell The rhyme scheme of Frost’s poem, aba / abc / bcb, vaguely resembles Dante”s tercets, aba bcb cdc etc Giovanni Stradano (Jan Van der Straet, 1523-1605), Flanders-born artist active mainly in Florence. From his illustrations to Dante’s Inferno Allusion A reference to something in history or previous literature. It is like a richly connotative word or a symbol, a means of suggesting more than it says. John Milton (1608-1674) Sonnet XIX WHEN I consider how my light is spent E're half my days, in this dark world and wide, And that one Talent which is death to hide, Lodg'd with me useless, though my Soul more bent To serve therewith my Maker, and present My true account, least he returning chide, Doth God exact day-labour, light deny'd, I fondly ask; But patience to prevent That murmur, soon replies, God doth not need Either man's work or his own gifts, who best Bear his milde yoak, they serve him best, his State Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed And post o're Land and Ocean without rest: They also serve who only stand and waite. Milton’s Sonnet He puns the term “talent” alluding to the parable of the talent told in Matthew 25,14-30 Milton Dictates the Lost Paradise to His Three Daughters, by Eugéne Delacroix c. 1826) The Holy Bible: King James Version The Gospel according to St. Matthew 25 14 For the kingdom of heaven is as a man traveling into a far country, who called his own servants, and delivered unto them his goods. 15 And unto one he gave five talents, to another two, and to another one; to every man according to his several ability; and straightway took his journey. 16 Then he that had received the five talents went and traded with the same, and made them other five talents. 17 And likewise he that had received two, he also gained other two. 18 But he that had received one went and digged in the earth, and hid his lord's money. 19 After a long time the lord of those servants cometh, and reckoneth with them. Matthew cont. 20 And so he that had received five talents came and brought other five talents, saying, Lord, thou deliveredst unto me five talents: behold, I have gained beside them five talents more. 21 His lord said unto him, Well done, thou good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things: enter thou into the joy of thy lord. 22 He also that had received two talents came and said, Lord, thou deliveredst unto me two talents: behold, I have gained two other talents beside them. Matthew cont. 23 His lord said unto him, Well done, good and faithful servant; thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things: enter thou into the joy of thy lord. 24 Then he which had received the one talent came and said, Lord, I knew thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou hast not sown, and gathering where thou hast not strewed: 25 and I was afraid, and went and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, there thou hast that is thine. 26 His lord answered and said unto him, Thou wicked and slothful servant, thou knewest that I reap where I sowed not, and gather where I have not strewed: Matthew cont. 27 thou oughtest therefore to have put my money to the exchangers, and then at my coming I should have received mine own with usury. 28 Take therefore the talent from him, and give it unto him which hath ten talents. 29 For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath 30 And cast ye the unprofitable servant into outer darkness: there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth. The title page of the 1611 first edition of the King James Bible