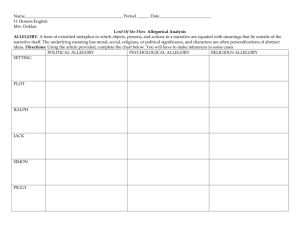

Romanticism in The Road

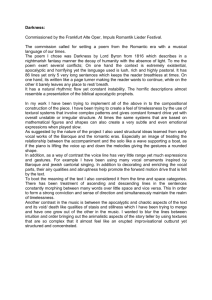

advertisement