Colombian Spanish

advertisement

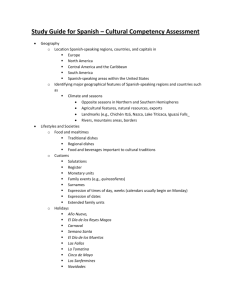

Columbia and Peru Spanish of Columbia Historical Overview • One of the most thoroughly studied nations of Latin America • Colombian Spanish has the reputation of being the ‘purest’ Spanish of Latin America • Varieties range from conservative highland dialects which are text-book perfect in terms of pronunciation, to the drastic consonantal reductions of the coastal lowlands • 1509: first Spanish visit to Colombia, by Alonso Ojeda • 1533: Cartegena de Indias becomes Spain’s major port in Tierra Firme • 1538: Santa Fe de Bogota is founded, culminating the colonisation efforts launched from the Caribbean • Turn of the 17th century: African slaves become the primary source of labour • 1718: Nueva Granada’s elevation in status means the creation of a university and other cultural and religious centres in Bogotá • Bogotá becomes linguistically placed closer to the Spanish elite • Highland Colombian speech is insulated from Atlantic and Caribbean influences • Cartagena is constantly in contact with linguistic innovations occurring elsewhere in the Caribbean and in southern Spain => great similarities between dialects Dialects of Colombia • There is no universally accepted classification of Colombian Spanish dialects • However, according to Floréz (1964) there are 7 dialect zones •Coastal (Atlantic and Pacific) •Antioquia •Nariño-Cauca • Tolima •Cundinamarca/Boyacá •Santander •Llanero (eastern/Amazonian lowlands) • Popular classification is determined by the pronunciation and choice of tú/vos/usted • Main distinction is between Costeños (coastal residents) and Cachacos (residents of the interior highlands) • Two ‘super-zones’ differentiated by retention/weakening of final /s/ and the pronunciation of final /n/, /l/ and /r/ • Colombia's Caribbean coast had a strong African presence => massive consonantal reductions • Phonetic variation is as much sociolinguistic as regional, given the extreme marginality of many communities. • Central highlands: characterised by phonological conservatism, a predominantly Spanish-derived lexicon and the use of usted (together with su mercé and vos) • The Colombian Amazon is considered a separate dialect zone • Spanish is often the second language • Spanish from the department of Nariño reflects a Quechua substratum not found elsewhere in Colombia • BOGOTANOS provide the prestige model to which others aspire Colombian Spanish Colombia -a few facts • National or official language: Spanish. (2nd largest population of Spanish speakers after Mexico). • Small communities of European languages, such as German, French, English, Italian and Portuguese in urban areas. • • There are 65 indigenous languages and two Creole languages: one in San Basilio de Palenque and one in San Andres. 500,000 speakers of American Indian languages (1997 Centro Colombiano de Estudios de Lenguas Aborígenes). • Literacy rate: 70%–80%. • Immigrant languages: Catalan-Valencian-Balear, Yagua, Yuhup. (Information mainly from Arango and Sánchez 1998; S. Levinsohn 1976a, 1976b, 1976c; SIL 1964–2003.) • The number of individual languages listed for Colombia is 100. Of those, 80 are living languages and 20 have no known speakers. • Capital: Bogotá • Topographically, Colombia is divided into 4 regions: the central highlands, the Caribbean lowlands, the Pacific lowlands, and Eastern Colombia (east of the Andes mountains). In this diverse geography one important feature is the 3 chains of high mountains (cordilleras) that cut the country from south to northeast. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=Colombia http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/economies/Americas/Colombia.html https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/co.html https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/co.html Acentos colombianos • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTKaWuX OimA&playnext=1&list=PL6411CB5A64F7E1A 4 Prestige In Colombia, the sociolinguistic prestige of the capital dialect is immense, and although coastal residents are rarely able to effect even a distant approximation to the speech of Bogotá, this mode of speaking is constantly held up as the goal of all educated Colombians. Lipski (207) General Phonological characteristics • Central highlands • Caribbean coast • Pacific coast • Amazonian region Central highlandsPhonological characteristics 1. Syllable- and word-final /s/ is retained as a sibilant [s]. 2. /s/ is at times aspirated in word-initial and intervocalic position • Nosotros ‘we’ nojotros Dissimilation in words containing a succession of /s/’s may cause one of the /s/’s (usually to emerge as [h]: necesario [nehesario] 3. Word-final /n/ is generally alveolar Lipski ( 209) Caribbean coastphonological characteristics 1. Syllable- and word /s/ is generally aspirated or lost throughout this region, although among educated urban speakers higher rates of retention of sibilant [s] are found. 2. Velarization of word-final /n/ predominates, with nasal elision and concomitant nasalization of the preceding vowel being an occasional alternative 3. The posterior fricative /x/ is a weak aspiration, and is subject to loss in intervocalic contexts. Lipski (211) Pacific coastphonological characteristics 1. Syllable- and word-final /s/ is aspirated or elided 2. Word-final /n/ is generally velarized; some instances of elision occur, and in a few small regions of the coast labialization to [m] can be found 3. Along much of the Pacific coast intervocalic /d/ may be pronounced as [r] Lipski (213) Amazonian regionlinguistic background • The Colombian Amazon does not form a unified linguistic region • Most native Spanish speakers have emigrated from elsewhere in the country • The indigenous population speak Spanish, if at all, as a second language. • Phonological characteristics = an amalgam of the prevailing tendencies of highland Colombia Lipski (213) Amazonian regionphonological characteristics 1. Syllable- and word-final /s/ is normally realized as a sibilant [s]. It sometimes disappears altogether, particularly when morphologically redundant e.g in: Los muchachos ‘the boys’ But rarely weakens to an aspiration 2. Word-final /n/ is sometimes velar 3. Intervocalic voiced obstruents are sometimes occlusive Lipski (213) Morphological characteristics • High and preferred use of: usted and vos throughout Colombia • Tú as a familiar pronoun is used consistently only in Cartagena and other Caribbean coastal areas • In Bogotá, su mercé competes with usted, tú and vos, while in western Colombia and the coastal regions su mercé does not occur • Along the Pacific coast usage is more variable both vos and tú can be heard, together with voseo and tuteo forms • Vos is more frequently heard in southwestern Colombia Lipski 213-214 Morphological characteristics continued • Colombian Spanish gives special preference to the diminutive –ico, predominantly after nouns and adjectives whose final consonants is /t/ or /d/: Momentico ‘just a moment’ Ratico ‘little while’ • In the Quecha-influenced highland region of Nariño, diminutive endings may be attached to clitic pronouns, especially in imperative constructions: Bájemelito ‘get it down for me’ • In the same region, imperative constructions are sometimes based on the future tense rather than on subjunctive forms; as in normal imperatives, clitic pronouns are attached to the end: Ayudarásle a tu hermano ‘you will help your brother’ Lipski (214) Syntactic characteristics 1. The use of ‘intensive ser’: Lo hice fue en el verano ‘I did it in the summer’ Teniamos era que trabajar mucho ‘We really had to work hard’ 2. Doubling of direct object clitics: Lo veo el caballo ‘I see the horse’ 3. Double negation (with no pause or intonational break occuring before the second no): No hablo inglés no Lipski (215) Lexical characteristics • The lexicon of the Colombian highlands is mostly derived from patrimonial Spanish words. • In other areas, the influences of African and indigenous languages are proportionately stronger. • Few individual lexical terms are regarded as distinctively ‘Colombian’; it is rather the combination of choices in an expanse of discourse that provides the most telling indications. Lipski (216) Examples of some of the most widely used Colombian lexical items • • • • • • • Argolla ‘wedding ring’ Biche ‘unripe’ (said of fruit) Cachifo/ cachifa ‘boy/girl’ Guandoca ‘jail’ (colloq.) Joto ‘small package’ Mamado ‘tired/fatigued’ Pipa ‘belly’ (colloq.) Lipski (217) Bibliography • http://www.ethnologue.com/show_map.asp? name=CO&seq=10 • http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/econo mies/Americas/Colombia.html • https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/theworld-factbook/geos/co.html • Lipski, J., 1994. Latin American Spanish. London and New York: Longman Perú Mapa Lingüístico de las lenguas prehispánicas de Perú En Perú se hablan entre 50 y 80 lenguas que pertenecen a 15 familias lingüísticas diferentes: Araua, Arewaka, Aimara, Cahuapana, Harakmbet, Jivaron, Lengua de las Islas, Panoa, Peba-Yagua, Quechua, Tanaca, Tucano, Tupí-Guaraní, Witoto, Záparo. ¿Qué encuentran los conquistadores en el s. XVI? Los conquistadores encuentran el imperio inca o Tahuantinsuyo, que comprendía parte de Perú, Bolivia, Ecuador y Chile, y algunas zonas de Colombia y Argentina, configurando el estado libre americano mayor de la América precolombina. Conquista del Perú A principios de 1532 el ejército incaico, inmerso en una guerra civil entre los dos hijos de Huayna Cápac, herederos al trono incaico, Huáscar y Atahualpa, se topó con el ejército español. Atahualpa fue hecho prisionero y ejecutado por mandato de Pizarro. La resistencia sin embargo duró hasta 1574. Los incas: difusión del Quechua • No eran originariamente hablantes de quechua, por sus orígenes altipláticos su lengua debió de ser aimara o puquina. • Adoptan el quechua como lengua y reservan la propia como jerga secreta reservada a la nobleza Imperial. • Se hacen cargo de la difusión del quechua. Debido a su fragmentación deben crear una lengua estándar que se difunde por todo el imperio a través del envío de maestros o del traslado de las elites dirigentes a lugares donde pudieran aprender la lengua general se da así una situación de bilingüismo o dialectalismo diglósico. Situación lingüística en el s.XVI • Los conquistadores se toparon con una selva de idiomas: entre 300 y 700 lenguas diferentes pertenecientes a más de 20 familias lingüísticas diferentes. • Quechua como lengua franca: La variedad estándar del quechua estaba extendida en la costa norteña, y de norte a sur a lo largo de las sierras andinas (Imperio incaico). Los préstamos al español ingresaron en las variantes propias del quechua estándar , que fue el primero que los conquistadores encontraron. Pero con la caída del Tahuantinsuyo, la lengua general se debilitó y volvieron a cobrar fuerza las variedades regionales. Política lingüística colonial • La idea primera fue la rápida hispanización idiomática (Carlos V). Pero pronto fue evidente la dificultad de la empresa y se favoreció entonces el uso y difusión de las lenguas indígenas con fines catequéticos(Felipe II): Se aprovechó la importancia y extensión que había logrado la lengua general (quechua estándar), e incluso se favoreció su extensión hacia zonas a las que no había llegado. Como la lengua general quechua no había logrado la total unificación lingüística del mundo andino, se utilizaron otras lenguas de gran difusión que se llamaron también lenguas generales (aimara y puquina). • A partir del siglo XVII las orientaciones de política lingüística, incluso en política religiosa, vuelven a tener un matiz coercitivo, que se agrava a finales del siglo XVIII (Carlos III), sobre todo tras la insurrección de Tupac Amaru (1970). Proceso de castellanización Gran diferencia entre la castellanización: • Región costeña: territorio de fácil acceso para la inmigración. Castellanización relativamente rápida. A esta situación contribuyó la crisis demográfica que sufrió en el siglo XV la población indígena a causa de la proliferación de epidemias. • Región andina: las sierras andinas fueron menos afectadas por el colapso demográfico y se constituyeron en zonas de mayor concentración de población indígena. La difusión del español fue un proceso lento. La difusión del español fue generando variaciones regionales, resultantes en parte de la convivencia con las lenguas indígenas. Dialectos del castellano peruano. • Castellano andino: variedad de marcado carácter rural, base del español peruano popular. Estigmatizado por los peruanos de la costa y de Lima. • Castellano ribereño (Lima): variedad de la capital y la costa. Pese a ser hablado por una minoría, constituye la base del español peruano “normativo”. Desde siempre ha constituido una variedad culta puesto que corresponde al español peninsular (en vez de al atlántico, general en América) ya que a Lima, como capital del virreinato, emigraban burócratas y dirigentes que hablaban el castellano propio de Toledo. • Castellano ribereño-andino: Variedad reciente que fusiona el habla de los andinos con el de los ribereños por la migración andina a Lima. • Castellano amazónico: se desarrolló por contacto del español andino y limeño con las lenguas amazónicas. • Castellano ecuatorial: se habla en el departamento de Tumbes. Independencia El Virreinato del Perú, creado por Carlos III en 1592, fue el último bastión contrarrevolucionario durante el proceso de independencia hispanoamericano que había empezado en 1808. La República del Perú se independiza finalmente en 1824 con la victoria de Simón Bolívar en Ayacucho. La castellanización colonial no fue efectiva. En 1824 la población indígena constituía la inmensa mayoría de la población y al extinguirse la dominación española, creyeron muchos que se produciría una indianización progresiva, pero ha sucedido todo lo contrario. Situación lenguas aborígenes LENGUA HABLANTES 1993 HABLANTES 2007 Castellano 80,27% 83,92% Quechua 16,59% 13,21% Aimara 2,29% 1,76% Otra lengua aborigen 0,67% 0,91% Lengua extranjera 0,18% 0,09% ¿Por qué se produce una castellanización tras la independencia? • En el siglo XX tiene gran influencia en los Andes el ideario progresista que ve en las lenguas y costumbres indígenas una traba para el desarrollo de la nación. • En los años cincuenta la migración rural a las ciudades aceleró el proceso de castellanización. Oficialización del Quechua • Paralelamente a la castellanización, nace un movimiento indigenista promovido por intelectuales de izquierda que logra la oficialidad de la lengua quechua en 1975: Decreto Ley 1975 del Gobierno Revolucionario Artículo 1º: Reconócese el quechua, al igual que el castellano, como lengua oficial de la República. • Este movimiento sin embargo no alcanza a los hablantes del aimara (más de un millón en los años setenta) que consideran su lengua un impedimento para integrarse socialmente. • La legislación peruana sin embargo, a pesar de que reconoce los derechos lingüísticos de los indígenas, dio un paso atrás al establecer en 1980 que el quechua y el aimara son cooficiales sólo en las zonas donde predominen, limitando así su oficialidad a áreas insignificantes e ignorando la existencia de quechua y aimara en las grandes ciudades, sobretodo en Lima, adonde la población indígena ha emigrado en los últimos años. • Como en el resto de estados americanos, la razón está relacionada con la creación a partir de un territorio multiétnico de un estado nacional unitario basado en la unidad lingüística. Además de ser el lenguaje de la administración, la educación y la religión, el español es hoy la lengua franca para las transacciones comerciales entre los indígenas. Se ha convertido en el lenguaje de la economía y de la movilidad social. Bibliografía • Academia peruana de la lengua: http://academiaperuanadelalengua.org/academia/principa l • Archivo digital de la legislación en el Perú: http://www.congreso.gob.pe/ntley/ConstitucionP.htm • Mar-Molinero. C, The Spanish Speaking World: a practical introduction to Sociolinguistics, London : Routledge, 1997. • Rivarola, J.L, El español de América en su historia, Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, Secretariado de Publicaciones e Intercambio Editorial, 2001. • Rosenblat, A, Los conquistadores y su lengua, Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1977. Peruvian Linguistic Features Linguistic Features •http://www.youtube.c om/watch?v=AwjlFs99 YDU&feature=related Extra-Hispanic Influences • Quechua • More than four centuries of contact between Spanish and Quechua have brought numerous lexical items into Peruvian and Latin American Spanish; it is possible that features of highland Peruvian pronunciation (assibilation of /r/ and reduction of unstressed vowels) have been influenced by native Peruvian languages. In linguistics, assibilation is the term for a sound change resulting in a sibilant consonant. It is commonly the final phase of palatalization. • African slavery • • Key component of Spanish colonial effort in Peru Few linguistic traces; songs in Afro-Hispanic pidgin Phonetics and phonology • Andean Highlands • • • • Lateral /ʎ/ in opposition to /y/ Velarization of /n/, complete elision occurring regularly The affricate /č/ often emerges as a fricative. Syllable finally, particularly before a pause, /r/ is most frequently a voiceless sibilant • The multiple /ř/ is normally a fricative rather than a trill, with an articulation approaching [ž]. – bilingual speakers; the /r/ in these combinations is a fricative or retroflex approximant, and in the case of /tr/ may fuse with the preceding consonant to produce a quasiaffricate. – Monolingual Spanish speakers usually pronounce the /r/ as a tap Andean Highlands, cont. • Syllable- and word-final /s/ is retained as [s]. Combined with a frequent voicing of word-final prevocalic /s/. In some regions, especially in Cuzco and Puno, this /s/ may be apicalized. – Vernacular level, although the /s/ almost never aspirates, complete elision of some cases of final /s/ does occur. This is particularly lexicalized , as in the frequent pronunciation of entonces as entonce. – In Cusco, many speakers introduce an interdental [θ] for /s/ in handful of words, particularly the numbers ‘once’, ‘doce’ and ‘trece’. • Posterior fricative /x/ receives audible friction, and is noticeably palatal before vowels. • Unstressed vowel reduction in the Peruvian Andes is extreme, particularly in the southern provinces. Vowels reduce to the point of elision principally in contact with /s/ • Quechua-dominant bilinguals often shift the stress of Spanish words to the penultimate syllable: corazón > corázon and plátano > platáno Lima and the central coast • Lima, as well as the rest of coastal Peru, is yeísta: the palatal lateral phoneme /ʎ/ has not been retained. • The posterior fricative /x/ is a weak aspiration, rarely acquiring velar or postpalatal friction • Intervocalic /d/ is routinely lost, even in rather formal speech styles and intervocalic /s/ also falls frequently. • The affricate /č/ does not normally lose its occlusive element. • In Lima, syllable final /r/ is either a tap or an alveolar fricative; the groove fricative or sibilant pronunciation found in the highlands does not occur. Among the lowest sociocultural strata /r/ may drop phrase-finally, particularly in verbal infinitives. • In Lima, and in most of coastal Peru except for the extreme south, wordfinal /n/ is velarized. Amazonian lowlands • Intervocalic /y/ is consistently an affricate, sometimes unvoiced, particularly among speakers of indigenous languages • The posterior fricative /x/ is a weak pharyngeal [h], and many Amazonian speakers give the same pronunciation to /f/. • Affricate /č/ often pronounced as a fricative • Syllable- and word-final /s/ is weakened and often elided, at times without passing through the stage of aspiration • There is no assibilation of /rr/ and /r/ • Intervocalic /b/, /d/ and /g/ are often occlusive rather than fricative • /f/ is usually [h] or sometimes [hw], even before unrounded vowels. Morphological Characteristics • Voseo. Indigenous speakers. Limited to the Southern highlands and the Altiplano (Puno) area, parts of Arequipa, and areas of the northern coast, lowest sociolinguistic levels. – Among the indigenous populations, forms in –ís prevail for the second conjugation (comís) while along the coast, forms in –és represent the second conjugation. • Pronouns. Among bilingual speakers with limited abilities in Spanish, choice of clitic pronouns is not always in accordance with monolingual Spanish norms. It is frequent for direct object clitics la and la to be used in contexts where an indirect object clitic is called for: – El los [les] dio algunas instrucciones. Syntactic Characteristics • Syntactic characteristics • Verb in a past tense may be followed by a subjunctive in a present tense: – El quería que lo hagamos • Object + Verb word order and in non-standard use of the gerund and other non-finite verb forms: – De mi mama en su casa estoy yendo – Comida tengo – La puerta sin cerrar nomás me había dormido • Various lexical nuances to do with clitics i.e. omission or misusage as well as various traits that have been carried over from Quechua such as preposing en to locative adverbs: vivo en acá and En arriba sale agua. Lexical Characteristics • Highly regionalised lexicon, reflecting ethnolinguistic considerations. Majority non-Hispanic source of lexical items is Quechua, many of these items are in general use throughout Latin America. • Among the most commonly-cited peruanismos are: – – – – – – Ancheta – a good bargain Chakra – small farm Choclo – corn on the cob Chompa – jumper/sweater Escobilla – brush/toothbrush Pisco – brandy distilled from grapes Bibliography • John M. Lipski,Latin American Spanish (Harlow: Longman, 1994) • Manuel Alvar,Manual de dialectología hispánica (Barcelona: Ariel, 1996)