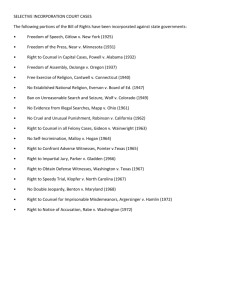

18 A fee schedule that provides more money for trial than

advertisement

ATLANTIC CENTER FOR CAPITAL REPRESENTATION BY: Marc Bookman, Esquire Identification No. 37320 1315 Walnut Street, Suite 1331 Philadelphia, PA 19107 mbookman@atlanticcenter.org (215) 732 - 2227 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA : COURT OF COMMON PLEAS CRIMINAL TRIAL DIVISION VS. : CHARGE: MURDER, ETC. SHIRVIN MCGARRELL : CP-51-CR-0014623-2009 : CP-51-CR-0001654-2011 CP-51-CR-0001658-2011 CP-51-CR-0001663-2011 CP-51-CR-0011460-2010 CP-51-CR-0015810-2010 ANTONIO RODRIQUEZ MALIQ POWELL DARYL YOUNG : : MOTION TO REQUIRE THE COMMONWEALTH TO PROVIDE CONSTITUTIONALLY ADEQUATE ATTORNEY FEES FOR THE DEFENSE OF THE ABOVE-CAPTIONED CAPITAL TRIALS, OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE, TO PRECLUDE THE COMMONWEALTH FROM SEEKING THE DEATH PENALTY Philadelphia County, the captioned cases, lays claim jurisdiction for the above- to the following remarkable statistics: 1) it pays its court-appointed attorneys less to prepare a capital case than any remotely comparable jurisdiction in the 2 country1; 2) it has the highest reversal rate of death penalty cases for ineffective assistance of counsel of any city in the country2; 3) its District Attorney seeks the death penalty more than any jurisdiction in the country3. These three facts are inextricably linked and result in the following scenario: the Commonwealth routinely and casually4 seeks This fact will be developed in detail infra. As of March 2011, a staggering 66 death sentences have been reversed from Philadelphia County for ineffective assistance of counsel since the modern Pennsylvania death penalty statute went into effect; no other jurisdiction is even close. 3 The three most comparable cities in terms of capital prosecution are Los Angeles, Houston (Harris County) and Phoenix (Maricopa County). Los Angeles County has sought the death penalty a little more than seven times a year for the past ten years. See “Death penalty phase could put Rowland Heights killer on short list of death row women,” Pasadena Star-News, 11/14/10. Per Jennifer Friedman, Assistant Special Circumstances Coordinator for the Los Angeles Public Defender’s Office, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office has consistently sought death in approximately 10-12% of death eligible cases over the past five years. During that same period, the Harris County District Attorney has gone to capital trials an average of 2.6 times a year per Kathryn Kase, Managing Attorney of the Houston Office and Senior Staff Attorney of the Trial Project of Texas Defender Services. Maricopa County goes to capital trials approximately 12-13 times a year (14 times in 2010, 13 times in 2009, less the three years before that, per Emily Skinner, Staff Attorney, Arizona Capital Representation Project). Philadelphia County does not keep statistics on capital trials, but five capital cases were scheduled in March, 2011. 4 Consider the matter of Commonwealth v. Campfield, CP-51-CR0006549-2009. The defendant was arrested on 10/24/08, and the Commonwealth filed notice that it would seek the death penalty on 6/3/09. On 10/19/10, almost two years after his arrest, 16 1 2 3 the death penalty, pays virtually nothing for the representation of the accused5, then suffers the consequences through reversal after reversal6. “Governments. . .quite properly spend vast sums of money to establish machinery to try defendants accused of crime,” Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 at 344 (1963); yet the government is spending virtually nothing to defend those same defendants in the instant cases. It is the contention of this motion that the fee structure currently in place in the above-captioned effective cases presents representation, and an unconstitutional that the right to barrier to effective representation is inextricably interlinked to the attorney’s right months after the Commonwealth’s decision to seek the death penalty, and only two weeks before the capital trial was set to begin, the defendant’s attorney filed a motion to bar the Commonwealth from seeking his execution. It turned out that neither the Commonwealth nor defense counsel had realized the defendant was only 16 years old at the time of the offense. See Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005). The case had remained a capital prosecution for close to a year and a half. 5 The connection between the Commonwealth’s pay scale for courtappointed counsel, the death sentences that result, and the reversal rate for ineffective assistance of counsel is not speculative. The Defender Association of Philadelphia, which has been handling 20% of Philadelphia’s capital cases since April, 1993, has two full time salaried attorneys assigned every capital case, and their capital caseload is regulated to comply with the ABA Guidelines. Since April of 1993, court-appointed counsel has taken more than 70 death verdicts; the Defender Association has not taken a single one. 6 A good example of the consequences of underfunding can be found in Commonwealth v. Cooper, 941 A.2d 655 (Pa. 2007). In that Philadelphia case, the “mitigation lawyer,” having not attended the trial, argued to the jury at sentencing that “an eye for an eye” only applies when a pregnant woman is killed. The lawyer did not realize that such was precisely the crime his client had committed. A new penalty phase was granted. 4 to fair compensation. Makemson v. Martin County, 491 So. 2d 1109 (Fla. 1986)7. As cogently noted in Martinez-Macias v. Collins, 979 F.2d 1067 (5th Cir. 1992), a reversal of a Texas death sentence after defense counsel was paid $11.84 per hour, “the justice system got only what it paid” for.” This motion will argue that the current fee schedule for capital representation in Philadelphia County is a violation of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and Article I, Sections 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 13 and 14 of the Pennsylvania Constitution, as well as 16 P.S. 9960.78 and 42 Pa. C. S. 9711 for the following reasons: 1) the fees paid to counsel are so low that counsel is presumed ineffective under Cronic v. United States, 466 U.S. 648 (1984) and the Pennsylvania Constitution; 2) the fee schedule represents an inherent conflict of interest for defense counsel such that ineffectiveness is presumed; and Makemson suggests that a mandatory cap interferes with the right to counsel in two senses: (1) It creates an economic disincentive for appointed counsel to spend more than a minimum amount of time on the case; and (2) It discourages competent attorneys from agreeing to a court appointment, thereby diminishing the pool of experienced talent available to the trial court. See Bottoson v. State, 674 So.2d 621 (Fla. 1996). 8 16 P.S. 9960.7 requires that an attorney appointed by the Court of Common Pleas “shall be awarded reasonable compensation, and reimbursement for expenses necessarily incurred, to be fixed by the judge of the court of common pleas sitting at the trial or hearing of the case and paid by the county.” 7 5 3) the combination interest of creates absurdly a low fees presumption of and conflicts of ineffectiveness of counsel. The claim, in essence, is taken directly from the landmark case of Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 at 71 (1932): “(I)n a capital case, where the defendant is unable to employ counsel. . . it is the duty of the court, whether requested or not, to assign counsel for him as a necessary requisite of due process of law; and that duty is not discharged by an assignment at such a time or under such circumstances as to preclude the giving of effective aid in the preparation and trial of the case (emphasis added).” See also Avery v. Alabama, 308 U.S. 444 (1940)(“ The Constitution's guarantee of assistance of counsel cannot be satisfied by mere formal appointment.”) In the instant cases, attorneys have been appointed, but under such circumstances that they cannot be effective in preparing and trying a capital circumstances accorded the case. disclosed, right of Again we hold counsel in from Powell: that defendants any “under substantial were sense. the not To decide otherwise, would simply be to ignore actualities.” 287 U.S. at 58. The actualities are below. The Fees Paid To Defense Counsel In Philadelphia County For 6 Capital Defense Are So Low That Ineffectiveness Must Be Presumed The concepts of "reasonable fee" and the constitutional requirements of effective assistance of counsel are related but not identical. A lawyer could receive a "reasonable fee" for very little work, but a minimal performance might not provide effective assistance of counsel in a particular case. The focus is not solely on providing the lawyer with a reasonable fee, although that is important, but on showing that the system is designed to ensure that an indigent defendant receives effective assistance of counsel. Simmons v. State Pub. Defender, 791 N.W.2d 69 (Iowa 2010). Thus, a reasonable fee schedule in a capital case must contemplate the work necessary to do an effective job; and the extensive requirements to prepare a capital case are by now well known and well documented. See, e.g., Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362 (2000); Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510 (2003); and Rompilla v. Beard, 545 U.S. 374 (2005). The United States Supreme Court has held that capital investigate evidence, and counsel prepare Williams, at has mental 396; an obligation health that and counsel to thoroughly other mitigating cannot meet this requirement by relying on “only rudimentary knowledge of [the defendant's] history from a narrow set of sources,” Wiggins, at 524; and that counsel has an obligation to investigate and 7 prepare to rebut aggravating circumstances put forth by the Commonwealth. Rompilla, at 386. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has also acknowledged the extensive requirements placed on defense counsel in a capital case, and particularly a penalty phase investigation. See generally, Commonwealth v. Smith, 995 A.2d 1143 (Pa. 2010); Commonwealth v. Gibson, 951 A.2d 1110 (Pa. 2008). Every capital case is different, of course, and as such each case requires different levels of preparation; nonetheless the 2003 ABA Guidelines9 quote studies indicating “that several thousand hours are representation10.” typically In 1994, required to provide appropriate Justice Blackmun estimated that a properly conducted capital trial can require hundreds of hours of investigation, preparation and lengthy trial proceedings. McFarland v. Scott, 512 U.S. 1256, 1257-58 (1994) (Blackmun, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari). In short, a competent and effective investigation and preparation of a capital case is a The ABA Guidelines have been cited by many courts, including the United States Supreme Court, as “guides to determining what is reasonable.” See Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510, 524 (2003); Rompilla v. Beard, 545 U.S. 374 (2005). 10 The most recent study regarding attorney hours in capital case preparation for federal cases is “Report to the Committee on Defender Services, Judicial Conference of the United States, Update on the Cost and Quality of Defense Representation in Federal Death Penalty Cases”, September 2010. The Study breaks down the attorney costs and mean number of hours spent on authorized and unauthorized cases, as well as cases that proceed to capital trials and cases that resolve themselves as pleas. Several thousand hours is an accurate estimate. See relevant pages attached as Exhibit A. 9 8 huge endeavor requiring a great deal County fee of time from defense counsel. The Philadelphia schedule for attorneys appointed in capital cases does not allow for the necessary investigation schedule except and preparation essentially on Williams, an 950 precludes entirely A.2d 294 detailed counsel charitable (Pa. above; from basis11. 2008), indeed being the effective Commonwealth anticipated fee this v. exact problem. The Court first found the pivotal and seminal Florida cases of Makemson v. Martin County, 491 So.2d 1109 (Fla. 1986), and White v. Board of Commissioners, 537 So.2d 1376, 1380 (Fla. 1989), inapposite. favorably by other Those Florida courts12, cases, ruled that subsequently flat fees cited and fee limitations were unconstitutional in all capital cases, finding that such cases by definition involved extraordinary circumstances and required unusual representation. The Williams Court distinguished those cases, however, by noting that “trial counsel did not contest the fee limitation, but rather, accepted Preparation fees are as follows: Homicide (Disposition After Arraignment But Prior To Trial) - $1333; Homicide (Disposition At Trial) - $2000; Mitigation Homicide Appointment/Co-Counsel $1700; Homicide 2d Chair Associate Counsel - $650. See attached Exhibit B. 12 See, e.g., Bailey v. State, 424 S.E.2d 503 (S.C. 1992); State ex rel. Wyoming Workers' Compensation Div. v. Brown, 805 P.2d 830 (Wyo. 1991); Joseph v. C.C. Oliphant Roofing Co., 711 A.2d 805 (Del. Super. 1997); Arnold V. Kemp, 813 S.W.2d 770 (Ark. 1991). 11 9 it and expended substantial efforts in the advancement of his client's cause. His explanation on post-conviction review was that he regarded the acceptance of court appointments as part of his duty as an attorney, and that the fee limitation had no effect upon his performance. . . While certainly in other circumstances such a fee limitation may be problematic, trial counsel's voluntary acceptance of full responsibility for the representation subject to the limitation does not fall within the narrow category of cases reflecting a breakdown in the adversary process as discussed in Cronic (emphasis added).” 950 A.2d at 313. Philadelphia The Williams County Court for was correct capital - the fees representation in are “problematic.” Unlike in Williams, however, counsel does contest the fee schedule in the instant cases. Seventeen “compensation defendants conducted for often capital years ago attorneys is Justice representing perversely trial can Blackmun low. involve wrote indigent Although hundreds a of that capital properly hours of investigation, preparation, and lengthy trial proceedings, many States severely limit the compensation paid for capital defense. Louisiana limits the compensation for court-appointed capitaldefense counsel to $1,000 for all pretrial preparation and trial proceedings. Kentucky pays a maximum of $2,500 for the same 10 services. Alabama limits reimbursement for out-of-court preparation in capital cases to a maximum of $1,000 each for the trial and penalty phases.” See McFarland, supra. But each of the states named by Justice Blackmun seventeen years ago now compensates its capital trial lawyers far more than Philadelphia. Twelve years ago Alabama changed its rate of compensation to $40 per hour out of court and $60 per hour in overhead court, plus expenses” an that additional averages hourly sum approximately for $30 “office per hour, thus bringing the hourly rates to 70/90. Wright v. Childree, 972 So.2d 771 (Ala. 2006). There is no limit to the hours submitted in a capital case in Alabama. Kentucky’s Department of Public Advocacy compensates the court-appointed attorneys at $75 per hour, and limits each attorney to $30,000; but that limit can be waived under extraordinary circumstances. See Robert L. Spangenberg, Rates Of Compensation For Court Appointed Counsel In Capital 200713. Cases At Louisiana, Trial: through A State the By State Louisiana Overview, Indigent June Defense Assistance Board (now the Louisiana Public Defender Board), has created regional offices to handle capital cases – for conflict cases the Shreveport state to pays $110 in an New hourly rate Orleans. ranging See from Spangenberg Confirmed in email exchange with Tom Griffiths, head of Department of Public Advocacy Capital Trial Unit, 3/7/11. 13 $75 in Report, 11 supra. Thus, dramatically every state modernized shamed its by fee Justice structure Blackmun for has capital representation. Other states pay capital lawyers far more than Philadelphia County. A random sampling14indicates the following: Virginia pays court-appointed attorneys $125 per hour with no limitations as to number of hours; Illinois, which abolished the death penalty on 3/10/11, was paying its capital attorneys $145.39 per hour as of 2007; Idaho pays a range of $90-150 per hour; Ohio, as of 2005, paid $46 per hour plus expenses. Florida pays an hourly rate of $100 and caps payment at $15,000, but this cap can be waived by the Court up to $30,000. See Justice Admin. Comm'n v. Lenamon, 19 So. 3d 1158 (Fla. 2009). Other states, such as Texas and Oklahoma, employ a combination of hourly rates and maximum fees; but every state’s maximum is at least five times greater than Philadelphia County, and usually far more. Even Mississippi, regularly ranked the poorest state in the country, recognized twenty-one years ago that a low flat fee (in that case $1000) could only be constitutional if the fee were accompanied by an hourly “reimbursement of actual expenses” that was a minimum of $25 per hour but would be higher subject to proof of an attorney’s actual overhead. Wilson v. State, 574 14 C. Attached is the entire Spangenberg Report, supra, as Exhibit 12 So.2d 1338 (Miss.1990). Twenty-one years later, Mississippi now pays conflict counsel $125 per hour without limitations to lead counsel and $100 per hour to associate counsel15. Philadelphia County stands alone as the lowest paying county in Pennsylvania as well. A random sampling of fees16 indicate that Allegheny County pays $50 per hour, Greene County pays $60, Warren County pays $70, Bradford County pays $94, Lycoming County pays $125, and Montgomery County pays $75 per hour out of court and $150 per hour in court. The federal courts for a capital case in Philadelphia pay “learned counsel” (the equivalent of Lead Counsel) $178 per hour without limitation; second chair, or CJA lawyers, are paid $125 per hour17. Philadelphia County is indeed an outlier in the United States as far as attorney fees for capital cases are concerned. Courts state’s failure have to established pay a counsel in capital cases. different reasonable In Makemson fee to remedies court and White, for a appointed supra, the Florida Court ordered a departure from the fee guidelines so Per Andre de Gruy of the Mississippi Office of Capital Defense Counsel, email on file with counsel. 16 Emails from practitioners in those jurisdictions on file with counsel. 17 And even Philadelphia County, while under the same financial constraints as many other jurisdictions, recognizes that lawyers working in the public sector must be paid a reasonable wage – indeed, attorneys defending the city in civil rights cases are paid $225 per hour by the county! 15 13 that reasonable fees could be paid. Finding that the fee structure interfered with the Sixth Amendment right to counsel, the Court noted that “we must not lose sight of the fact that it is the defendant's right to effective representation rather than the attorney's right to fair compensation which is our focus. We find the two inextricably interlinked.” Bailey v. State, 424 S.E.2d 503 (S.C. 1992), quoting Makemson, supra, noted that “the link between compensation and the quality of representation remains too clear,” and followed the Florida court in ordering reasonable attorneys’ fees be paid. Bailey v. State, 424 S.E.2d 503 (S.C. 1992), quoting Makemson, supra, noted that “the link between compensation and the quality of representation remains too clear,” and ordered reasonable attorneys’ fees be paid. In N.Y. County Lawyers' Ass'n v. State, 196 Misc. 2d 761 (N.Y. Supreme Court, 2003), the court found that fees of $40 per hour in court and $25 per hour out of court was insufficient to ensure “the constitutional and statutory obligation . . . that qualified assigned private counsel are available and able to provide meaningful and effective representation,” and ordered payment of $90 per hour in and out of court without limitation. Other courts, focusing on the unfairness of confiscatory fees to the lawyers, reached the same conclusion as the Florida and South fee Carolina Supreme Courts and required that the 14 structure be made reasonable. See, State v. Lynch, 796 P.2d 1150 (Okla. 1990). Some courts, faced with inadequate funding for court appointed attorneys, have ordered the criminal proceedings halted until adequate funding becomes available. See State v. Citizen, 898 So. 2d 325 (La. 2005); generally, Lavallee v. Justices in the Hampden Superior Court, 812 N.E.2d 895 (Mass. 2004). And State v. Young, 172 P.3d 138 (N.M.2007), is perhaps most instructive of all. In Young, a complex capital case, $96,500 had been allotted lead counsel and $73,000 for second counsel; counsel for the defendant alleged that another $50,000 for each counsel would be necessary (at $75 per hour) to ensure effective representation. The trial court agreed, but the New Mexico legislature did not appropriate the necessary funds. The New Mexico Supreme Court stated the following: “We are persuaded by the evidence in the record that the attorneys for the defendants are not receiving adequate compensation. The inadequacy of compensation in this case makes it unlikely that any lawyer could provide effective assistance, and therefore, as instructed by the United States Supreme Court, ineffectiveness is properly presumed without inquiry into actual performance. See Cronic, 466 at 661. (noting that there may be cases where "circumstances ma[k]e it so unlikely that any lawyer could provide effective assistance that 15 ineffectiveness [is] properly presumed without inquiry into actual performance at trial.").” Faced with a Cronic violation, the Court indeed found that defense counsels’ compensation to be inadequate, and thus a violation of the defendants’ Sixth Amendment rights to effective representation. The Court’s remedy was to stay the death penalty unless and until the funds in question were made available to defense counsel. Young, supra, 172 P.3d at 144. Financially speaking, Young is as far from the instant cases as the sun from Pluto; but the point is the same. Inadequate compensation in a capital case is inextricably linked to ineffectiveness of counsel, and this Court now faces the least compensation of any jurisdiction in the United States. “(T)he State assumes the obligation to provide assigned counsel with a reasonable basis upon which they can carry out their profession's profiteering threaten tension the responsibility, or undue financial adversarial between without adherence process to sacrifice. by either The creating professional personal current an rates unacceptable standards and the financial burden an attorney assumes when serving” as courtappointed counsel. New York County Lawyers' Association v. State of New York, 763 N.Y.S. 2d 397 (2003). This Court must now order reasonable compensation, or bar the death penalty due to the 16 Commonwealth’s refusal to properly fund defense counsel in a capital case. The Philadelphia County Fee Schedule Represents An Inherent Conflict Of Interest Such That Ineffectiveness Of Counsel Must Be Presumed The Philadelphia County fee schedule pays lead counsel $2000 as a preparation fee, and $1700 to Mitigation Homicide Appointment/Co-Counsel. If the case proceeds to trial, lead counsel is paid $200 for three hours of court time or less, and $400 per day for more than three hours. Mitigation counsel is paid $100/$200 for court time. When the penalty phase begins, the rates reverse for lead and mitigation counsel. Continuances are expressly not compensable. This fee schedule represents the following possible conflicts of interest: 1) Given the absurdly low preparation fee, counsel has a strong financial interest in advising his client to go to trial, where he can double his fee in a mere five days18; A fee schedule that provides more money for trial than negotiation is not only a conflict of interest but may be unethical as well. Judge Renee Cardwell Hughes of the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas, in a high profile case involving the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, noted that an agreement to pay attorney fees only upon an acquittal may discourage negotiation even if that would be the best path to take. Stephen Gillers, a well-known Professor of Ethics at New York University Law School, said that “arrangements to pay legal 18 17 2) Counsel has a financial quickly as possible incentive to go to trial as and prepare as little as possible, given that she will receive the same fee for one hour’s preparation or two thousand; 3) Counsel has no incentive to request a continuance, even if a continuance is crucially needed, as continuances are not compensated; 4) Mitigation counsel has a financial interest in preparing for a penalty phase as little as possible, since he will make $1700 regardless of hours spent in preparation; 5) Mitigation counsel, making a mere $200 per day for a possible eight hours of work, has an interest in assuring that a trial end quickly; 6) Mitigation counsel has the same financial interest in proceeding to trial the case as lead counsel. In short, the fee schedule is so transparently rife with conflict issues that it is almost unreasonable to believe that court-appointed counsel might rise above it. See, e.g., fees only if acquitted could result in divided loyalties, for both lawyer and client.” See, Priests and Judge in Abuse Case Spar Over Legal Fees, Katherine Q. Seelye, New York Times, 3/14/11. While the Philadelphia fee schedule does not pay a bonus for acquittals, there is a clear financial interest for the attorney in proceeding to trial rather than negotiating a resolution. 18 Bailey v. State, supra at 424 S.E.2d 503, 506 (1992) (“[I]t would be foolish to ignore the very real possibility that a lawyer may not be capable of properly balancing the obligation to expend the proper amount of time in an appointed criminal matter where the fees involved are nominal, with his personal concerns to earn a decent living by devoting his time to matters wherein he will be reasonably compensated. The indigent client, of course, will be the one to suffer the consequences if the balancing job is not It is this obvious if speculative that was made explicit in the original). interest condemnation of flat tilted fees in and his favor.”) 2003 compensation (emphasis in conflict of ABA Guidelines caps (Guideline 9.1)(“Counsel in death penalty cases should be fully compensated at a rate quality that legal is commensurate representation and with the reflects provision the of high extraordinary responsibilities inherent in death penalty representation...Flat fees, caps on compensation, and lump-sum contracts are improper in death penalty cases”). What is not speculative is the Commonwealth’s refusal to remunerate for a continuance request, whether granted or denied. Seeking a continuance when a capital case is not ready for trial is essential to good practice, and numerous cases have been reversed for failure to grant a proper continuance in a 19 capital case, even though the decision for the trial judge is discretionary. See, e.g., Powell v. Collins, 332 F.3d 376 (6th Cir. 2003); People v. Lovejoy, 235 Ill.2d 97, 919 N.E.2d 843 (2009); State v. Rogers, 352 N.C. 119, 529 S.E.2d 671 (2000). Nor is a continuance request a simple matter of walking to the bar of the court and asking – in order to effectively preserve the record should the request be denied, counsel must fully document her reasons the continuance should be granted. The Commonwealth’s refusal to compensate for this critical motion is an overt financial disincentive for counsel to follow a necessary and often constitutionally required path, and as such presents a clear conflict of interest for counsel who know their case is not properly prepared but knows as well that any work aimed at gaining necessary time will be unremunerated. In short, the Philadelphia County fee schedule represents innumerable potential conflicts of interest for a terribly underpaid courtappointed counsel to navigate, and, as noted supra in State v. Bailey, it is the indigent client who suffers from even a subconscious desire on the part of his lawyer to simply make a living. The Combination of Absurdly Low Fees and the Inherent Conflicts of Interest Built into the Fee Schedule Create a Presumption of Ineffectiveness 20 While flat fees have been roundly condemned as an inappropriate remuneration scheme in capital cases exactly because of the conflicts of interest inherent in such a payment plan, it is the low fees in the instant cases that enhance the conflicts and make them real. Effective capital practitioners know that many capital cases are best resolved by a guilty plea, and that resolution may take many hours of time with a client, his family, and representatives of the Commonwealth to achieve this goal. Yet resolving a case by plea bargain will actually cost defense counsel money, as he will surely not be compensated for the hours required, and will earn no money from the per diem. Persuading a client to take a waiver trial rather than a jury trial may also be a sound course in a capital case; again, however, financial counsel will interests, as be a advising waiver a trial decision will be against his considerably shorter than a jury trial and will thus pay less per diem. ABA Guideline 10.9.1 (The Duty To Seek An Agreed-Upon Disposition) explicitly discusses the advantages of guilty pleas19, waiver trials20, agreements to forgo various legal rights21, and many Counsel at every stage of the case should explore. . . the types of pleas that may be agreed to, such as a plea of guilty, a conditional plea of guilty, or a plea of nolo contendere or other plea which does not require the client to personally acknowledge guilt, along with the advantages and disadvantages of each. Guideline 10.9.1, B.5 20 Counsel at every stage of the case should explore. . .an 19 21 other options short of a death sentence; but each option requires hours of work without real compensation. Conclusion The Philadelphia County fee system for court-appointed counsel in capital cases is designed to be ineffective: lawyers are not compensated for the work they need to do, and they are encouraged to make decisions that inure to the detriment of their clients and the court system22. The court-appointed lawyers that are presently handling the bulk of the capital cases in Philadelphia necessary are handling motion practice, a caseload23 investigation, that precludes the and development of mitigation, simply because they cannot make a living wage from the fee schedule as it is constituted. Based on the instant allegations as contained in this agreement to permit a judge to perform functions relative to guilt or sentence that would otherwise be performed by a jury or vice versa. Guideline 10.9.1, B.8.b 21 Counsel at every stage of the case should explore. . .an agreement to forego in whole or part legal remedies such as appeals, motions for post-conviction relief, and/or parole or clemency applications. Guideline 10.9.1, B.8.d 22 Presumably a court system would welcome more guilty pleas and waiver trials than full-blown capital jury trials. 23 Neither the Guidelines nor the case law specifies an appropriate number of capital cases that a court-appointed attorney should handle at a given time. Given the requirements a capital case entails, supra, it is obvious that the number of death penalty cases a court-appointed attorney should handle must be severely limited. Much like Justice Stewart’s pronouncement that you know obscenity when you see it, this Court will know that the caseload of many court-appointed attorneys is far too overwhelming to even attempt an effective job in an individual case. 22 Motion, Defendants in the above-captioned cases and their court-appointed attorneys ask this Court to grant a hearing and allow counsel to establish the facts necessary to support one of the two remedies requested: a reasonable fee to continue the representation required by the United States Constitution and the Pennsylvania Constitution in a capital case, or a bar precluding the Commonwealth from seeking the death penalty in the instant cases. Respectfully Submitted, _______________________ Marc Bookman, Esq. On Behalf of Michael Farrell, Esq. William Bowe, Esq. Daniel Rendine, Esq. Judith Rubino, Esq.