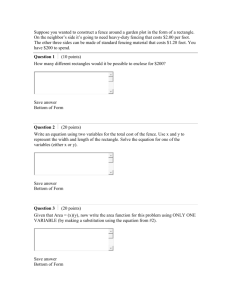

Final Report Example

advertisement

The Student Conservation Association Desert Restoration Corps Owens Peak Wilderness Scott Nordquist, Project Leader 9/28/2010-5/17/2011 Table of Contents Introduction Project Overview………………………...…...……………………………………………..3 Site…………….....…………………………………………………………………………..3 Project Goals………………………………………………………………………………..4 The Crew………..…………………………………………………………………………...5 Description of Work Projects Hard Barriers & Fence.………………...…...……………………………………………...6 Restoration………………………...…...……………………………………………………8 Outreach……..………………………...…...……………………………………………….9 Overall Project Accomplishments…...…………………………………………………..10 Team Highlights………………...…...…………………………………….………………11 Field Operations Schedule………………………...…...…………………………….………………………13 Transportation…………………...…...……………………………………………………13 Equipment & Supplies…………...…...…………..………………………………………13 Housing………………………...…...……………………………………………………...13 Resources & Contacts Primary Contact………………...…...……………………………………………….……14 Enrichment Opportunities……...…...…………………………………………….………14 Acknowledgements Thank you……………………...…...…………………………………...…………………15 Data Maps GIS Shape files…………………...…...………………………………………………..…16 Cover photo: A view of “base camp” in Indian Wells Canyon, from the Five Fingers 2|Page Project Overview: The Desert Restoration Corps is a growing project in southern California conducted through a partnership between The Student Conservation Association and the Bureau of Land Management. The mission of the project is to inventory, physically restore, and then rehabilitate illegal off-road vehicle routes in designated wilderness or critical habitat areas in the California desert. Tracks caused by illegal OHV use last for decades without active restoration efforts. They scar the wilderness, fragment sensitive wildlife habitat, prevent re-growth of native vegetation, degrade scenic values, and encourage continued use. Though DRC crews have worked in the Southern California since 1999, this was the first season for a crew to be based in the Owens Peak Wilderness. The major emphasis of the work was building fences to stop vehicle use on closed routes and in wilderness. The crew working on these projects included a Project Leader and six Corps Members. The Project Leader coordinated with the agency contact, Wilderness Specialist Marty Dickes, to prioritize work projects. Site Intro: The Owens Peak Wilderness is located 15 miles northwest of Ridgecrest, CA and encompasses the rugged eastern face of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and its valleys, canyons, and alluvial fans. It is a transition zone between Great Basin Desert, Mojave Desert, and the Sierra Nevada ecological zones. Vegetation varies widely, with creosote scrub, cacti, Joshua Trees, cottonwood, oak, annual wildflowers in the lower elevations to pinyon-juniper woodlands and digger/grey pines in the upper elevations. Wildlife includes rodents, lizards, rabbits, snakes, coyotes, mule deer, bear, prairie falcon, raven and numerous bird species. The wilderness is popular for camping, hunting, hiking, horseback riding, rock climbing, bird watching and wildflower-viewing. The Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail runs the entire length of the wilderness from Walker Pass in the south to Lamont Meadows in the north. Other popular hikes include the Owens Peak trail as well as routes up up Short and Sand Canyon. The wilderness is enjoyed by equestrians who combine closed vehicle routes with other trails to complete circuits of the area. Schoolhouse/Heller Rocks and Five Fingers are common rock climbing locations. Bird watchers frequent the riparian corridor of the various canyons. Sand Canyon is home to SEEP, the Sand Canyon Environmental Education Project associated with local elementary schools. 3|Page Project Goals: To manage the wilderness in accordance with national wilderness goals: - To provide for the long-term protection and preservation of the area’s wilderness character under the principle of non-degradation. The area’s natural condition, opportunities for solitude, opportunities for primitive and unconfined types of recreation and any ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic or historical value present will be managed so that they remain unimpaired. - To manage the wilderness area for the use and enjoyment of visitors in a manner that will leave the area unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness. The wilderness resource will be dominant in all management decisions where a choice must be made between preservation of wilderness character and visitor use. - To manage the area using the minimum tool, equipment, or structure necessary to successfully, safely, and economically accomplish the objective, the chosen tool, equipment, or structure should be the one that least degrades wilderness values temporarily or permanently. Management will seek to preserve spontaneity of use and as much freedom from regulation as possible. To manage nonconforming but accepted uses permitted by the Wilderness Act and subsequent laws in a manner that will prevent unnecessary or undue degradation of the area's wilderness character. Nonconforming uses are the exception rather that the rule; therefore, emphasis is placed on maintaining wilderness character. - Purpose: The work completed was necessary to meet the requirements of the Wilderness Act of 1964, the California Desert Protection Act of 1994, BLM regulations and policies regarding use and administration of designated wilderness areas, the Federal Land Management Policy Act of 1976, the California Desert Conservation Area Plan as amended in 1980, and the West Mojave Plan Amendment of 2005. 4|Page The Crew Diana Portner A 25-year-old Illinois native, she recently graduated from the University of Wisconsin – Madison with a degree in Psychology and a certificate in Environmental Studies. Since then, she has been pursuing her love of the environment through various internships. Her next adventure will take her to the University of Michigan as a grad student in the School of Natural Resources and Environment. Brogan Tooley Straight out of high school, Brogan flew 3,000 miles across the country from Maine to California. Brogan found the desert the perfect place for personal growth and learning. She enjoyed teaching her crew about the constellations, chiseling perfect notches and never stopped laughing. Her next step will be college, to further pursue her love of art and of the environment. Jonathon Hallemeier Growing up in the Midwest, his interest in deserts and desert restoration was a fairly recent development, stemming from a few early hikes in Utah and then two years of trekking in Egypt and the surrounding region while studying Arabic and Arab oral folk traditions. In the future, Jon hopes to combine his interest in Arabic and the Middle East with his passion for conservation issues. Ryan Hughes After spending a summer on a trail crew in eastern Washington’s Umatilla National Forest, Ryan ventured to the California desert. For the summer, he plans to head north again to the Umatilla National Forest, where he will be working on a Forest Service fire crew. With help from the SCA, Ryan has been given the opportunity to explore the Western lands far from his native Oklahoma, and he is not turning back soon. Michelle Ort Michelle was born in Toronto, Canada, but grew up in the American Midwest. In coming to the Desert Restoration Corps, Michelle traveled far outside her comfort zone. Straight off of a year in northern Russia and never having camped before in her life, for Michelle this was season of new experiences. She loved it all, from learning to build fence, to doing push-ups every morning, to sleeping under the stars every night. Scott Nordquist – Project Leader Before coming to the Desert Restoration Corps, Scott worked a summer in his beloved Washington Cascades and guided hikes around the highlands of Guatemala. Though he missed the trees and water of the Pacific Northwest, he quickly fell in love with the wide open spaces and harsh conditions of the Mojave. He hopes to continue working and living outside throughout the Americas. 5|Page Description of Work Projects Hard Barriers & Fence Most of the season was spent working on various fence projects. Bollard and wire fence was built using four strands of smooth wire, with each wire set at a designated height to accommodate wildlife such as jackrabbits, deer, and tortoises. Metal T-posts were placed 10 feet apart to ensure strength and dead men, or single bollards, were incorporated to support T-posts on uneven terrain. Each change in direction required a corner H-brace. Independent breakaway fences were constructed across washes to limit Jon & Matt pounding T-posts along the Aqueduct fence damage caused by storms. Five Fingers Fence A 290 meter fence, including one breakaway fence, was built to prohibit access to an illegal hillclimb leading into the wilderness near Five Fingers. Previous closure attempts using signage and vehicle barriers had proven ineffective. The former trespass route totaled 852 meters. High-Bank Fence A 178 meter fence was constructed across a large wash parallel to CA Hwy 178 at the south end of the wilderness. Though it is surrounded by private property, riders accessed the wash where it crossed the Aqueduct Rd, utilizing it to connect to an illegal network of routes on the north side of the highway. Golden Valley Wilderness Fence The agency contact encouraged the Owens Peak Wilderness crew to partner with the Golden Valley Wilderness crew on each area’s respective fence projects. The Owens Peak crew spent two hitches assisting with the five-mile fence along the southern border of the Golden Valley Wilderness. The High-Bank Fence crossing the wash 6|Page Aqueduct Fence The crew’s main project was a continuous 3282 meter (~2 mile) fence built along the wilderness boundary, south of Indian Wells Canyon. The fence paralleled the Upper Aqueduct Rd, with a standard of 125’ given as right-of-way for the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power. The fence blocked off five incursions, closing approximately six miles of illegal routes. The importance of building a high-quality, aesthetically pleasing fence was stressed by the agency contact. To meet this expectation, the fence had an impressive 37 dead men, 23 corner H-braces, and five breakaway fences. The rough terrain and compact soil made this fence especially challenging and time consuming. Michelle, Brogan and Ryan finish an H-brace, leaving a gap for an equestrian step-over. Golden Valley Project Leader Shannon Waldron and Jon ensure a straight section of fence despite the difficult terrain along the Aqueduct Fence. 7|Page Site definition An August 2010 wildfire exposed a set of hard barriers along the wilderness boundary near the popular Owens Peak trailhead. Without vegetation to define a natural parking zone, the entire area was at risk of becoming a parking lot. The crew’s first project of the season was to relocate the hard barriers and define a logical parking zone to allow for optimal post-burn vegetation recovery and minimize the area impacted. Restoration Vertical Mulch Illegal routes were restored by combining vertical mulch with horizontal mulch and seed bank transfer. The concept behind vertical mulch was to plant dead plant matter upright in the ground so that it resembled live plants. Bouquets of mulch were constructed from branches of dead plants still in the ground of whole plants occasionally found in washes. Horizontal mulch, such as broken Joshua Tree limbs, was used as ground cover in empty spaces along the incursion. It allows the soil to be enriched from decomposing mulch and promotes future growth in that area. Matching mulch to the size, color, and density of the surrounding plants caused the incursion to blend with its surroundings to the point that it virtually disappeared. Along with disguising the route, these dead plants will continue to catch seeds in the wind and provide shade for animals and new plants. The last step, seed bank transfer, was completed by collecting seeds from the base of live plants and transferring them into shallow pits under the piece of vertical mulch. The amount of restoration on an incursion was based on the line of sight from the legal route of travel. Restoration - before Restoration - after In addition to the typical restoration goal of making a route disappear, two former Jeep trails were restored into hiker/equestrian trails. This proved to be a unique combination of trail building and desert restoration completed with the use of berms, soil decompaction, and the techniques described above with vertical mulch. 8|Page Illegal Jeep trail leading through wilderness to Schoolhouse Rocks Restored to hiker/equestrian trail with a stepover incorporated into the fence design Erosion Control The crew performed erosion control on three different areas, the hillclimb leading to Five Fingers, and two All-Corps project in Blythe, CA, and the Jawbone-Butterbredt ACEC. Steep routes compact soil and encourage the channelization of water. To eliminate these ruts, the crew installed check dams across the incursion to slow the speed of water and redistribute soil. On a particularly rocky, wide and deep incursion, the crew employed a different method of harvesting rock and soil and filling the incursion to match the surrounding landscape. Outreach Finding engaging and productive opportunities for public outreach in the Ridgecrest area was a challenge. The crew was still able to enjoy a variety of different events, including educating users on the Rand Mountain Permit, participating in a cleanup project in Sand Canyon, teaching along with the Sand Canyon Environmental Education Project (SEEP), and tabling at an Earth Day event hosted by Cerro Coso Community College. Diana, Ryan and Scott at Earth Day 9|Page Overall Project Accomplishments Restoration # of Incursions Line of Sight (m) Linear Meters Restored Area Restored # Dead Plants # Seed Pits # Live Plants Berms (m) 6 611 692 1450 370 363 58 3 Check Dams 47 Hard Barriers Fence constructed (meters) Other hard barrier (#, meters) Active trespasses closed (miles) 3750 76, 178 8+ Outreach Contacts Made (#): Events Led & Attended (#, #): Number of People Reached: SCA materials distributed (type, #)? Other materials distributed (type, #): 3 1, 2 135 Fliers, 65 Friend of Jawbone maps, 15 Scott examines the erosion control project below Five Fingers 10 | P a g e Team Highlights The Owens Peak crew spent most of the season taking pleasure and pride in building high-quality fence each day. Flush notches, plumb & level H-braces, and straight T-post lines aside, they enjoyed these highlights: Golden Valley crew member Marko Capoferri (right) accompanies Jon hiking through the Golden Valley Trained as Wilderness First Responders Visited the Indian Wells Valley Water District Hiked to the top of Owens Peak (elev. 8452) Certified S-212 Power Saws Learned about birding at the Kern Audubon Preserve Worked with the three other Ridgecrest crews in their work areas Took a field trip to the US Forest Service Fire Ecology Burn Lab in Riverside Trained to operate ATVs Completed a three day Leave No Trace Trainer course in Joshua Tree NP Joined a group of dedicated locals to clean up the Sand Canyon ACEC Walked five miles while carrying over two tons of fencing supplies during one epic day of work in Golden Valley Went on a spring Wildflower Walk in the Desert Tortoise Natural Area Created a unique time zone to mentally avoid 4:30 a.m. wake-ups. Subscribed to a box of fresh produce through Community Supported Agriculture Hosted each of the other Ridgecrest crews for at least one work day Survived the cold, dark winter to enjoy the emergence of spring wildlife Challenged each other to meet personal goals throughout the season Endured the unpredictable, tent shredding winds of the Eastern Sierra Participated in two arduous All-Corps projects with the other DRC crews Witnessed the smoke clouds and strange aircraft of the China Lake NAWS 11 | P a g e Brogan holding a gigantic Daikon radish from the CSA Jon and Ryan finish an H-brace on the Five Fingers Fence project “No matter what the weather, we always managed to enjoy our evenings singing, reading stories, or having deep discussions, and most of the time slept like babies under the stars after our hard work.” –Diana Portner Jon, Ryan, Michelle & Diana relax on Cuddeback Lake after a day’s work in Golden Valley 12 | P a g e Field Operations Schedule Work was primarily based on a 10-day hitch schedule, with five days off in between. Each crewmember had the responsibility to plan a menu and organize work for two hitches. Day one was spent preparing food and packing up tool and supplies to head to the field that evening. Eight full 8-hour work days were spent based out of the nearest suitable campsite to that hitch’s work. Day ten was used to pack up camp and drive back to town to clean, maintain and store everything that went to the field. Transportation A Chevy Suburban and Dodge Ram were the primary means of transportation. The bed of the Dodge was often filled to capacity with tools and fence supplies. A 10’ trailer, complete with a 100-gallon water tank, transported everything necessary to setup a field-based base camp. Having access to an additional work trailer to haul fence supplies would have been very beneficial to eliminate extra trips out of the field to resupply. Equipment & Supplies SCA provided a tool cache at the beginning of the season. This was supplemented with purchases from our Field Supplies budget in order to have everything necessary to: Build fence Restore incursions Collect data Camp in the field for 10 days at a time Housing The crew was housed in a two-bedroom, one-bath house in Ridgecrest. Food was prepared in the house kitchen on day one. The house had internet access and a crew computer, which was used to write hitch reports, store data and photos, produce outreach materials, and update the blog on the SCA website. The small size of the house, especially the kitchen, was a prohibiting factor to get out to the field more efficiently. 13 | P a g e Resources & Contacts Primary Contact: Marty Dickes, Wilderness Specialist Bureau of Land Management 300 S Richmond Rd, Ridgecrest CA 93555 Phone: (760) 384-5400. Email: mdickes@blm.gov Enrichment Opportunities Alison Sheehey, Outreach Director Kern River Audubon Preserve 18747 Hwy 178. Weldon CA 93283 Phone (760) 378-2029 Keith Axelson, avid birder Sageland Ranch PO Box 967, Weldon, CA 93283 Phone (760) 371-6116 Kimberly Schwartz, Student Activities Officer Cerro Coso Community College 3000 College Heights Blvd, Ridgecrest CA 93555 Phone: (760) 384-6353 E-mail: kjkelly@cerrocoso.edu Sally Haase, Research Forester Pacific Southwest Research Station 4955 Canyon Crest Dr, Riverside CA 92507 Phone (951) 680-1551 Carrie Woods, Wildlife Biologist Bureau of Land Management 300 S Richmond Rd, Ridgecrest CA 93555 Phone: (760) 384-5400. Email: cwoods@blm.gov 14 | P a g e Thank you… Marty Dickes, for sharing your love of wilderness Keith Axelson, for showing how to enjoy living in the desert Carrie Woods, for your plant knowledge and a great BBQ Bob Weinbeck, for your dedication to Sand Canyon Everyone at SEEP, for helping kids enjoy the outdoors Sally Haase, for giving a tour of your work Kim Schwartz, for encouraging The DRC to perform outreach Alison Sheehey, for teaching how to make bird calls Steve Hester, for fostering a culture of open communication and personal growth Jill Kolodzne, for showing the value of laughing and teaching at the same time Abundant Harvest Organics, for providing a lesson in local food with each week Jamie Weleber and Darren Gruetze, for taking time to make site visits, helping the crew become better teachers, and your dedication to the DRC Everyone we never met who gave us the opportunity to live & work in the desert! “The view from the top was a reminder of why we love working out here and what we have accomplished this year” – Michelle Ort Scott, Diana, Brogan, Ryan, Michelle & Jon on top of Owens Peak 15 | P a g e GIS Map 16 | P a g e