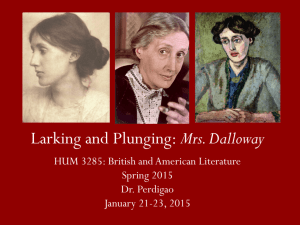

Class Powerpoint for Mrs.Dalloway

advertisement

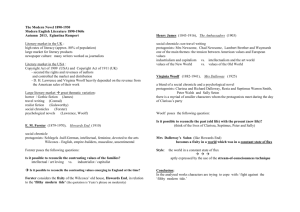

Mrs. Dalloway Virgina Woolf Virgina Woolf 1882: Born in London, named Adeline Virginia Stephen. 1895: Mother died; suffered her first mental breakdown. 1904: had a second breakdown for the death of her father. Bloomsbury Group formed 1912: married to Leonard Woolf. 1913: her third serious breakdown; finished her first novel, The Voyage Out. 1917: Bought a hand printing press, Hogarth House. First published a couple of experimental short stories; ex: The Mark on the Wall & Kew Gardens. 1922: Jacob’s Room published. Met Mrs. Harold Nicolson – Vita Sackville West. 1925: Mrs. Dalloway 1927: To the Lighthouse 1931: The Waves 1941: Committed suicide by drowning herself in the River Ouse. Writing Style: Virginia rebelled against what she called the “materialism” novelists and sought a more delicate rendering of those aspects of consciousness in which she felt that the truth of human experience really lay. After two novels, The Voyage Out and Night and Day, cast in traditional form, she developed her own style. These technical experiments helped revolutionize fictional technique and perfected a form of interior monologue in her novels. The publication of To the Lighthouse (1927) and Orlando (1929) established Virginia as a major novelist. She explores not only subtlety problems of personal identity and personal relationships but also a great deal of social criticism, such as the reflection on the position of women. Her strong support of women’s rights can be viewed in a series of lectures published as A Room of One’s Own (1929) and in a collection essays, Three Guineas (1938). Stream of Consciousness Definition “……to describe the unbroken flow of thought and awareness in the waking mind; it has since been adopted to describe a narrative method in modern fiction. Long passages of introspection, describing in some detail what passes through a character’s mind,…” “… the continuous flow of a character’s mental process, in which sense perceptions mingle with conscious and half-conscious thoughts, memories, expectations, feelings, and random associations. “ Woolf's goal is to move steadily away from traditional forms of fiction, to come "closer to life," to capture the moments of life, even though those times make life both terribly wonderful and completely unbearable. Main Themes: The sea as symbolic of life: The ebb and flow of life. Doubling: Many critics describe Septimus as Clarissa's doppelganger, the alternate persona, the darker, more internal personality compared to Clarissa's very social and singular outlook. The doubling portrays the polarity of the self and exposes the positive-negative relationship inherent in humanity. The intersection of time and timelessness: Woolf creates a new novelistic structure in Mrs. Dalloway wherein her prose has blurred the distinction between dream and reality, between the past and present. Social commentary: Woolf also strived to illustrate the vain artificiality of Clarissa's life and her involvement in it. Even though Clarissa is effected by Septimus' death and is bombarded by profound thoughts throughout the novel, she is also a woman for whom a party is her greatest offering to society. The thread of the Prime Minister throughout, the near fulfilling of Peter's prophecy concerning Clarissa's role, and the characters of the doctors, Hugh Whitbread, and Lady Bruton as compared to the tragically mishandled plight of Septimus, throw a critical light upon the social circle examined by Woolf. The world of the sane and the insane The critic, Ruotolo, excellently develops the idea behind the theme: "Estranged from the sanity of others, ‘rooted to the pavement,' the veteran [Septimus] asks ‘for what purpose' he is present. Virginia Woolf's novel honors and extends his question. He perceives a beauty in existence that his age has almost totally disregarded; his vision of new life... is a source of joy as well as madness. a study of insanity and suicide; life and death With this book, Woolf wrote that she wanted "to give life and death, sanity and insanity." Truths are subjective and changeable, as the plot streams back and forth in space and time. Uncertainty of life and isolation Life suddenly seems meaningless to both Septimus and Mrs. Dalloway. They are alone; the people who love them are alone. They exist in a place apart, though really the same, as the rest of the people of London. They are outsiders. If Mrs. Dalloway is haunted by her invisibility, Septimus is haunted by ghosts of a different sort. Drawing from her own bouts of insanity, Woolf paints Septimus. He is a troubled war hero, who has returned from war only to discover that he can't forget, that the voices of his dead comrades continue to haunt him, and that "the world itself is without meaning." Then, what is the difference between Mrs. Dalloway and Septimus? They are both lonely; they both feel disconnected. Why does one commit suicide, while the other survives to plan another party? Questions for Discussion: 1. In Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf combines interior with omniscient descriptions of character and scene. How does the author handle the transition between the interior and the exterior? Which characters' points of view are primary to the novel; which minor characters are given their own points of view? Why, and how does Woolf handle the transitions from one point of view to another? How do the shifting points of view, together with that of the author, combine to create a portrait of Clarissa and her milieu? Does this kind of novelistic portraiture resonate with other artistic movement's of Woolf's time? 2. Woolf saw Septimus Warren Smith as an essential counterpoint to Clarissa Dalloway. What specific comparisons and contrasts are drawn between the two? What primary images are associated, respectively, with Clarissa and with Septimus? What is the significance of Septimus making his first appearance as Clarissa, from her florist's window, watches the mysterious motor car in Bond Street? 3. What was Clarissa's relationship with Sally Seton? What is the significance of Sally's reentry into Clarissa's life after so much time? What role does Sally play in Clarissa's past and in her present? 4. What is Woolf's purpose in creating a range of female characters of various ages and social classes--from Clarissa herself and Lady Millicent Burton to Sally Seton, Doris Kilman, Lucrezia Smith, and Maisie Johnson? Does she present a comparable range of male characters? 5. Clarissa's movements through London, along with the comings and goings of other characters, are given in some geographic detail. Do the patterns of movement and the characters' intersecting routes establish a pattern? If so, how do those physical patterns reflect important internal patterns of thought, memory, feelings, and attitudes? What is the view of London that we come away with? 6. As the day and the novel proceed, the hours and half hours are sounded by a variety of clocks (for instance, Big Ben strikes noon at the novel's exact midpoint). What is the effect of the time being constantly announced on the novel's structure and on our sense of the pace of the characters' lives? What hours in association with which events are explicitly sounded? Why? Is there significance in Big Ben being the chief announcer of time? 7. Woolf shifts scenes between past and present, primarily through Clarissa's, Septimus's, and others' memories? Does this device successfully establish the importance of the past as a shaping influence on and an informing component of the present? Which characters promote this idea? Does Woolf seem to believe this holds true for individuals as it does for society as a whole? 8. Threats of disorder and death recur throughout the novel, culminating in Septimus's suicide and repeating later in Sir William Bradshaw's report of that suicide at Clarissa's party. When do thoughts or images of disorder and death appear in the novel, and in connection with which characters? What are those characters' attitudes concerning death? 9. Clarissa and others have a heightened sense of the "splendid achievement" and continuity of English history, culture, and tradition. How do Clarissa and others respond to that history and culture? What specific elements of English history and culture are viewed as primary? How does Clarissa's attitude, specifically, compare with Septimus's attitude on these points? 10. As he leaves Regent's Park, Peter sees and hears "a tall quivering shape, . . . a battered woman" singing of love and death: "the voice of an ancient spring spouting from the earth . . ." singing "the ancient song." What is Peter's reaction and what significance does the battered woman and her ancient song have for the novel as a whole? 11. Clarissa reads lines from Shakespeare's Cymbeline (IV, ii) from an open book in a shop window: "Fear no more the heat o' the sun / Nor the furious winter's rages./Thou thy worldly task hast done, / Home art gone and ta'en thy wages: / Golden lads and girls all must, / As chimneysweepers, come to dust." These lines are alluded to many times. What importance do they have for Clarissa, Septimus, and the novel's principal themes? What fears do Clarissa and other characters experience? What is Shakespeare’s role in this novel? Which plays are cited, and how? How do different characters “use” Shakespeare, and what does this tell us about them? 12. Why does Woolf end the novel with Clarissa as seen through Peter's eyes? Why does he experience feelings of "terror," "ecstasy," and "extraordinary excitement" in her presence? What is the significance of those feelings, and do we as readers share them? 13. Maureen Howard asserts that “If ever there was a work conceived in response to the state of the novel, a consciously ‘modern’ novel, it is Mrs. Dalloway…The novel, [Woolf] knew, had only to be reimagined, an enormous task, but what a grand and immediate occasion” (viii). How exactly is this novel “modern”--consciously or unconsciously? 14. The Foreword cites Woolf’s essay in The Common Reader: “In the vast catastrophe of the European war our emotions had to be broken up for us, and put at an angle from us, before we could allow ourselves to feel them in poetry or fiction” (xiii). In discussing the loss of romance in A Room of One’s Own, Woolf asks “Shall we lay the blame on the war?…But why say ‘blame’? Why, if it was an illusion, not praise the catastrophe, whatever it was, that destroyed illusion and put truth in its place?” (15). How does World War I function in Mrs. Dalloway? Is it a catastrophe to be blamed? Has it destroyed illusions?