A Model Student Conduct Code for the 21st Century

advertisement

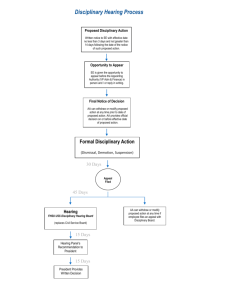

A Model Student Conduct Code for the 21st Century Edward N. Stoner II enstoner@adelphia.net John Wesley Lowery, Ph.D. jlowery@gwm.sc.edu Introducing the Presenters • Ed Stoner, B.A. DePauw Univ. ‘69, J.D. U.Va. ‘72; retired partner, Reed Smith LLP; admitted to practice: PA, FL, US Sup Ct; former President and Board Chair, NACUA; founding member of ASJA; Board member, CALCASA. Author of ‘90 Model Code. • John Lowery, B.A. U.Va. ‘90, M.Ed. U.So.Carolina ‘92, Ph.D. Bowling Green S.U. ‘00; former ASJA Bd of Dir.; former NASPA Bd of Dir; Assistant Professor of Higher Education and Student Affairs, University of South Carolina. Thomas Jefferson and the Spirit of Insubordination • Riots at the Charlottesville campus caused by alcohol . . . resulting in assaults on professors and other “ungentlemanly” conduct. • Mr. Jefferson and two other leaders examined student conduct and the state’s commitment to such a University. Mr. Jefferson and the Spirit of Insubordination “The article of discipline is the most difficult in American education. Premature ideas of independence, too little repressed by parents, beget a spirit of insubordination, which is the great obstacle to science with us, and a principal cause of its decay since the revolution. I look to it with dismay in our institution, as a breaker ahead, which I am far from being confident we shall be able to weather.” —Letter to Thomas Cooper (1822). How to Use the New Model Code How to Use the New Model Code, 31 JCUL 1 • It is a “Model”, a research tool. • Electronically searchable. • It has three distinct sections: a. b. c. Narrative Introduction: History/Sources (pp. 1-17) The Model Code itself (pp. 18-63) A Model Hearing Script (pp. 64-77) Working With Your Lawyer • Bad result often flows from your lawyer “learning about the case on the walk to the courthouse.” • Get your lawyer to observe a hearing. Builds his/her confidence for judicial conferences Can improve process by observation • Ask the attorney who will defend you to take part in the periodic revision process. There are many “legal” alternatives your attorney can suggest. This will help to assure that the choices are ones your attorney can defend as well as possible and give you the most flexibility. The Audit Process • Plan for a regular Conduct Code review. • Take care in selecting the revision “author.”Some of the worst code problems stem from it having been written by one who is “out of the loop.” • Counsel should be involved but be clear you a not creating a law school moot court or junior legal system, but something based upon educational values that can be run smoothly by non lawyers. The Audit Process • Learn your campus history (what “works” despite all odds!). • Keep a file of a problem case and problematic provisions. • Documents problems under the old Code using specific cases to identify obstacles to correct outcomes. • Review statistics of types of cases for consistency and other clues. The Audit Process: Who Participates? • Advisor, Hearing Board Chair, Board Members are key resources • Campus politics/history shape committee membership • Involve many constituencies for INPUT, not as members: Educational moment. • Be cautious about using law faculty or consultants who do not understand core value of student affairs Basic Concepts of the New Model Code Student Discipline Procedure v. Criminal Procedure • Most Important Point: The criminal law is NOT a helpful or controlling model for how a college deals with students who violate college rules. • Who says so? We’ll give you three citations: there are more in the Model. • Highly recommend: General Order, 45 FRD 133, 142 (W.D. Mo. 1968) (en banc). See Model fn. 19. • “School regulations are not to be measured by the standards which prevail for criminal law and for criminal procedure.” Text at fn. 3. Esteban v. Central Mo. State Coll., 415 F.2d 1077 (8th Cir. 1968) (Blackmun, J.). Student Discipline Procedure v. Criminal Procedure • “[Student disciplinary proceedings] are not criminal in nature as they only regulate the relationship between the student and the university, and have no bearing on a student’s legal rights or obligations under state or federal criminal laws.” United States v. Miami Univ., 91 F.Supp.2d 1132, 1157 (S.D. Ohio 2000); Model fn. 20. Constitutional Due Process v. Institutional Due Process • Constitutional Due Process: Minimal, even at state schools. Goss and Dixon: Some kind of notice, some kind of hearing. Fn. 29. • Institutional Due Process: We must do what we said we’d do. So write your conduct code carefully; don’t use vague words like “fairness” or “due process.” Fn. 34. The “Golden” Rule • Treat all students with equal care, concern, honor and dignity. (p. 15). • Honored status as students is what drives our treatment. • Examples: appeal, counseling, attend hearing, hear outcomes, advisors…. Dr. Dennis C. Golden, President, Fontbonne University What is the Purpose of Your Code? • What IS a student code? It is the way a college defines its behavioral standards for students to be part of our community. Contrast: criminal law: retribution, punishment; civil law: monetary compensation. What is the Purpose of Your Code? • It is ok to expect superior ethical and moral standards from our students. Fn 20: “Standards so established [on campus] may require…superior ethical and moral behavior.” (Gen Order) “Courts will reach the right results if they do not allow themselves to be distracted by analogies from criminal law or administrative law or elsewhere….” (Charles Alan Wright). Use Plain English, Not Legalese • “Responsible” or “in violation” v. “Guilty” • “Board members” v. “Prosecutors” • “Accused student” v. “Defendant” • “No violation” found v. “Innocent” • “Information” v. “Evidence” • See fn. 50. Key Points of Student Discipline Practice and Procedure in the New Model Code Pointers within the Model Code • Define student, pp. 18-19 • Who determines what happened (student conduct board, pp. 20-21) • Who sets sanctions (student affairs professional, pp. 21-22) • To what conduct does the code apply, e.g., “off campus” (pp. 24-26) and “after discovered” Pointers in the Model Code • What are the rules? (Keep them modern; e.g. Disorderly conduct p. 31). • How does the process work? (pp. 38-54). If resolution short of a hearing does not occur, how does a hearing work? (pp. 40-54). Review 4 (a-j) at pp. 40-44. • Advisors, including attorneys (if allowed), to behave as Potted Plants (pp. 41-43). Dealing With Students’ Attorneys • Role as “advisor”— same as other advisors. • “Right to counsel”— Gabrilowitz v. Newman. See fns. 126-129. • Jones v. Northern Illinois Univ., 1996 WL 19453 (N.D. Ill. Jan. 2, 1996) and Osteen v. Henley, 13 F.2d 221 (7th Cir. 1993). Rules of Evidence? • “Formal rules of process, procedure, and/or technical rules of evidence, such as are applied in criminal or civil court, are not used in Student Code proceedings.” (Model Code, p. 44). • Supreme Court of Massachusetts: “It is not the business of lawyers and judges to tell universities what statements they may consider and what statements they must reject.” (See fn. 133). Sexual Conduct Case Pointers • The fearful witness (pp. 50-54). • Student Impact Statements (not “victim” impact statements, See fns. 153, 219, 220). • Treat students who claim they are victims of other students with same dignity as those accused of violating rules. (e.g., pp. 23, 56). Solving a FERPA Puzzle • LeRoy Rooker at the Univ. of Vermont. • Sources of “The Problem”: filing systems for most matters involving no victim student; embarrassment in telling sexual assault victim that sanction was lenient; and maybe some criminal law confusion. Solving a FERPA Puzzle • Places solved in the Model Code: p. 23 # 17; p. 56 (para 3-b) (printer’s error had this as para 2-b), 58. See fn. 233. • "Key question: Ask: to whom does this record "relate"? Model urges you to consider that records about students claiming to be victims do, in law and logic, "relate" to them. Disclosure of Hearing Outcomes FERPA was amended in 1990 by the Clery Act to allow colleges & universities to inform the alleged victim of a “crime of violence” of the outcome of the student disciplinary proceeding against the alleged perpetrator. (§99.31) The amendments to the Student Right-to-Know and Campus Security Act in 1992 require colleges and universities to inform the victim of an alleged sexual assault of the final outcome of the disciplinary proceeding against the alleged perpetrator. Disclosure of Hearing Outcomes FERPA was further amended in 1998 to allow the release of the final results of a disciplinary proceedings to the public in certain limited circumstances: 1. The student has been accused of a violation of the code which meets the definition of a crime of violence or non-forcible sexual offense. 2. The accused student is found responsible as a result of a student disciplinary proceeding of those violations. Crime of Violence Rather than relying on the definition of a “crime of violence” at 18 U.S.C. 16, the Department of Education has provided an all inclusive list of “crimes of violence”: • • • • • • Arson Assault offenses Burglary Robbery Kidnapping/abduction Forcible and nonforcible sex offenses • Criminal homicide— manslaughter by negligence • Criminal homicide— murder and nonnegligent manslaughter • Destruction, damage, and vandalism of property (§99.39) Using the New Model Hearing Script A Description of the Model Hearing Script • We are free to adopt a system that reflects the nature of our academic community, that does not victimize students when they take part, and that is NOT modeled after court systems. (pp. 64-77). The “Style” of Your Discipline Board Hearing (See Model, pp. 64-77) • Old Model: A Junior Court of Law, maybe even with students wearing mock robes and pretending to be trial lawyers. • New Model: An educational meeting, forum provided by school to determine if rules were violated and, if so, the sanction. Like any educational meeting: informal. Lawyer-like histrionics are discouraged. The Model Hearing Script for your consideration: Review pp. 40-44. • No need for “presenters” or prosecutor. Avoids the risk of unbalanced skills and issue of furnishing same skilled presenter for all students and gives control to board. • The process is controlled by and questioning is lead by the student conduct board members. • Pointer: No “sides”—all are our students (not “ours” and “theirs”). No “cross-examination” as lawyers think of it. • You’re not running a trial practice seminar! Compare: faculty committee. Credibility • No opinion required. But please consider saying: We believed student x rather than student y. See fn. 236. • One person's word is enough! Just ask Judge Lancaster! See fn. 187. Conclusion and Final Comments Key Point: Use your Educational Judgment and Common Sense • Courts give deference to Educational Judgment. See fn. 16. • If a suggestion is contrary to your common sense, it is probably a bad choice. • Choose options because they are educationally valuable: be wary of any claim something is Legally Required. Appeal and Remand • Limit Levels of Appeals (Zero v. 2, 3) • Limit Scope of Appeals (Model pp. 60-62). inappropriate sanction did not follow process lack of substantial information “new information” • Possible outcomes are specifically listed and discussed: Remand, increase or decrease sanctions, etc. (Model, p. 62 at fn. 191.) Appeal and Remand • Educate Reviewers—A frequent error is to act as NEW finders of fact (wrong: cannot judge credibility). Another error: Hear only one side. Contrast: trial de novo. • Instead, on appeal, credit credibility determinations by board, judge sufficiency of evidence on that basis. Written “opinion” by Board (credibility). Remember Brandeis lesson... New Cases Reaffirm Long Standing Principles • Ruane v. Shippensburg Univ., 871 A.2d 859 (Pa. Cmwlth. 2005) (state institution). • Gomes v. University of Maine, 365 F.Supp. 2d 6, (D.Me. 2005) (granting summary judgment) (Woodcock, J.). • Sexual Assault resource: www.calcasa.org. • Excellent student conduct training: Donald D. Gehring Campus Judicial Affairs Training Institute, each June. http://asja.tamu.edu Mr. Jefferson and the End of the Story • “[The imposition of student discipline] determined the welldisposed among them to frown upon everything of the kind hereafter, and the ill-disposed return to order from fear, if not from better motives. A perfect subordination has succeeded, entire respect towards the professors, and industry, order, and quiet the most exemplary, has prevailed ever since. Every one is sensible of the strength which the institution has derived from what appeared at first to threaten its foundation. We have no further fear of any thing of the kind from the present set, but as at the next term their numbers will be more than doubled by the accession of an additional band, as unbroken as these were, we mean to be prepared….” (fn 59). —Letter to Ellen W. Coolidge A Model Student Conduct Code for the 21st Century Edward N. Stoner II 232 Buttonwood Lane Tavernier, FL 33070 enstoner@adelphia.net 412.519.8844 Dr. John Wesley Lowery Assistant Professor of Higher Education and Student Affairs University of South Carolina Wardlaw College, Room 318 Columbia, SC 29208 803-777-4158 office 803-777-3090 fax jlowery@gwm.sc.edu