WG LRA 2012 - Sites@UCI - University of California, Irvine

advertisement

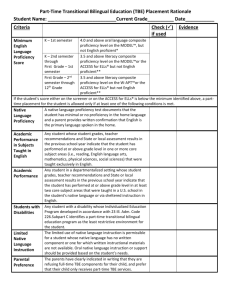

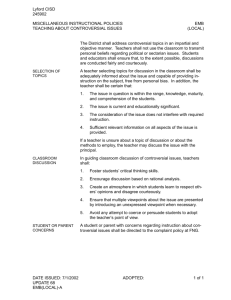

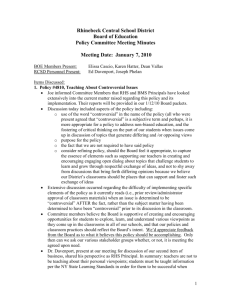

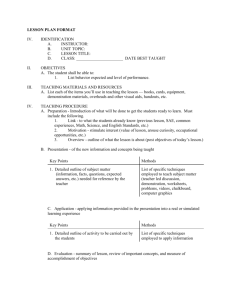

Overview Paper #1 - An efficacy trial of Word Generation: Results from the first year of a randomized trial Joshua F Lawrence (University of California, Irvine), E. Juliana Paré-Blagoev (Strategic Education Research Partnership), Amy Crosson (LRDC, University of Pittsburgh), David Francis (University of Houston), Catherine E. Snow (Harvard University) Paper #2 - Patterns of Students’ Vocabulary Improvement from One-time Instruction and Review Instruction Wenliang He (University of California, Irvine), Emily Galloway, Claire White, Catherine Snow (Harvard University), Judy Hsu (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) Paper #3 Engaging Middle School Students in Classroom Discussion of Controversial Issues Alex Lin (University of California, Irvine), Joshua F Lawrence (University of California, Irvine), Patrick Hurley (Strategic Education Research Partnership) Paper #4 - Heterogeneous Treatment Effects for Redesignated Fluent English Proficient Middle School Students Jin Kyoung Hwang (University of California, Irvine), Joshua F Lawrence (University of California, Irvine), Elaine Mo (University of the Pacific), Patrick Hurley (Strategic Education Research Partnership) Academic Vocabulary Instruction Across the Content Areas: Results from a Randomized Trial of the Word Generation Program Word Generation: Weekly Schedule Monday Paragraph introduces words Tuesday-Thursday Math-ScienceSocial Studies Friday Writing with focus words Day 1 - Launch Introduction to weekly passage, containing academic vocabulary, built around a question that can support discussion and debate, (comprehension questions, student friendly definitions included) Day 2 - Science Thinking experiments to promote discussion and scientific reasoning Topic: not directly related to stem cell research but clearly a link could be made Target Words: investigate, theory, obtain Background Information: Countries have different views about citizens carrying guns. In some countries the import and export of guns is illegal. Subsequently, no citizen can obtain a gun in those countries (text continues). Questions: Are people more aggressive in countries that allow handguns? Hypothesis: Citizens of countries that allow handguns are more aggressive than citizens of countries that do not. Materials: Procedure: Data: Conclusion: What evidence do you have that supports your conclusion? Day 3 - Math Mathematics problems using some of the target words: a) Students can work in pairs b) Whole class discussion c) Open-response (show/explain how you got your answer) 1. Some people believe that embryonic stem cell research is important. They think this because scientists use these cells to investigate diseases. Scientists try to find cures for these diseases, and for conditions like paralysis. Other people believe that embryonic stem cell research is wrong. They think this because scientists must destroy embryos to obtain these cells. In a recent poll, 40.75% of people said that the government should not pay for embryonic stem cell research. Which decimal is equivalent to 40.75%? A) 4.075 B) .4075 * C) .04075 D) .02 Day 4- Social Studies Developing positions on the issue set out in the passage, to help the class frame the debate. Note: these are optional. The class may want to develop its own positions! Positions: 1. Scientists should not be allowed to investigate cures for disease using stem cells from embryos. This is trying to “play God”. 2. Destroying an embryo to get the stem cells is murder. 3. The government should pay for embryonic stem cell research. This could lead to cures for many injuries and diseases. 4. Scientists should be allowed to do research on embryonic stem cells, but the government should not pay for it because many taxpayers oppose it. Day 5 - ELA Writing Activity: Should the government pay for stem cell research? Give evidence to support your position. Mon – Introduce words in ELA class Tues – Math activity with target words Wed – Social studies debate Thurs – Science activity with target words Friday – Writing activity Focus on classroom discussion • There are some studies on talk exposure and peer interactions and vocabulary for young children • Studies on discussion of older children have examined outcomes like reading comprehension, math, science, and philosophy content. • Connections to ELA and SS student outcomes is strong. Research Questions How engaging were classroom discussions in treatment and control schools? Were there differences in quality across content areas? Did schools that participated in the Word Generation program demonstrate improved classroom discussion? Did participating in the Word Generation program impact students’ knowledge of the academic words taught? Did participation effect students’ general vocabulary knowledge? Did improved classroom discussion mediate the impact of the Word Generation program on students’ academic vocabulary knowledge? District / School Control Schools School Code District Grade 6 Contribution Grade 7 Contribution Grade 8 Contribution Total Contribution 1 3 5 6 11 13 20 35 36 30 31 32 33 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 11 24 24 38 17 27 11 21 69 7 6 12 14 281 17 15 19 17 25 43 12 14 74 0 4 0 10 250 0 0 0 0 15 59 0 17 0 0 0 0 0 91 28 39 43 55 57 129 23 52 143 7 10 12 24 622 8 9 10 12 15 16 17 18 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 0 39 41 32 0 54 5 43 0 0 18 0 0 0 0 232 29 28 41 33 60 87 0 29 5 0 13 0 45 60 0 430 0 11 26 23 0 115 0 0 0 12 17 15 0 0 51 270 29 78 108 88 60 256 5 72 5 12 48 15 45 60 51 932 Total Word Generation Schools Total Support for Participation (1 – 3) the teacher created a well-ordered and respectful environment that enabled engagement with lesson content and participation in the discussion • 1 was reserved for classrooms that were chaotic or there was student hostility or lack of participation • 3 points were scored if nearly all students appeared consistently engaged with minimal side talk and distractions Student Engagement (1 – 3) percent of students participating or attending to the classroom discussion. • 1 was awarded if around a quarter of the students participated in discussion during the observation period • 3 was awarded when 50% to 100% of students participated in discussion Teacher Talk Moves (1 – 5) Teachers’ use of open-ended questions and follow-up questions asking students to explain their thinking or provide evidence for their ideas. • 1 was given to classroom discussions in which all teacher questions had single, known answers (closed questions). • 5 reserved for classrooms where the teacher initiated a range of question types including open-ended questions and also asked students to provide evidence or explain their ideas more clearly. Substantive contributions (1 – 5) The level of students’ contributions to the discussion was rated on a five point scale. • 1 perfunctory answers were given the lowest ratings • 5 multiple students elaborated ideas and explaining their thinking while providing evidence. (In these classrooms students also asked each other to explain their thinking or explicitly link their own to others’ contributions.) Composite Scores Composite Discussion Quality Rating (1 – 4) – Overall quality score for each class. Weighted School Level Discussion Quality Ratings (z score Control Schools Word Generation Schools 30 20 10 0 Feb Mar Apr May Jun Feb Mar Observation Date Apr May Jun Academic Vocabulary Knowledge • 36-item multiple-choice test General Vocabulary Knowledge Participants completed level 6 or level 7/9 of the Gates-MacGinitie vocabulary assessment (depending on their grade level).. Covariates Grade-level proficiency scores School percent free and reduced lunch School percent special education Student grade level RQ1 How engaging were classroom discussions in treatment and control schools? Were there differences in quality across content areas? Did schools that participated in the Word Generation program demonstrate improved classroom discussion? Control Schools Word Generation Schools 30 20 10 0 1 2 3 4 1 2 Composite Discussion Quality Rating 3 4 Content-Area Observed Math (n = 48) Word Generation Schools Control Schools n Mean n Mean n 1.85 25 2.90 23 2.35 48 + 1.05 1.08 47 + 0.43 0.47 54 + 0.35 0.41 64 + 0.29 0.35 213 + 0.52 0.58 1.85 (0.84) 27 (0.85) Social Studies (n = 54) 2.24 Total (n = 213 ) 2.26 2.28 (0.97) 20 (0.93) 24 (0.83) ELA (n = 63) Total Mean (0.80) Science (n = 47) Difference Effect (WG size Control (Cohen's Schools) d) 2.59 (0.90) 30 (0.86) 36 2.55 (0.89) (0.73) 2.07 113 2.59 (0.86) (0.85) 2.03 2.43 (0.86) 27 2.39 (0.82) 100 2.31 (0.89) RQ2 Did participating in the Word Generation program impact students’ knowledge of the academic words taught? Did participation affect students’ general vocabulary knowledge? Treatment Effect ∆= 𝛿𝑇 − 𝛿𝐶 = 𝜇𝑇,𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡 − 𝜇𝑇,𝑝𝑟𝑒 − 𝜇𝐶,𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡 − 𝜇𝐶,𝑝𝑟𝑒 𝜎 Effect Sizes (Student Level) Outcome Overall Sample Measure Mean Academic Vocabulary GatesMacGinitie Vocabulary Pre Post 18.58 19.94 (6.21) (7.08) 505.26 510.9 (32.46) (35.0) n Control Pre 1540 18.04 Post 18.8 n Word Generation δC Pre δT δT δC Effect Size 0.16 1400 501.54 508.44 570 6.9 507.5 512.59 830 5.05 -1.85 -0.06 (33.49) (36.37) 20.7 n 922 1.76 1.00 (6.02) (6.83) 618 0.76 18.94 Post (6.21) (7.14) (31.6) (33.87) Basic Model 𝑉𝑂𝐶𝐴𝐵𝑖𝑗 = 𝛽0𝑗 + 𝛽1𝑗 𝐶𝐸𝑁𝑇𝐸𝑅𝐸𝐷_𝑉𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑗 + 𝐺𝑅𝐴𝐷𝐸𝑖𝑗 + 𝜀𝑖𝑗 𝛽0𝑗 = 𝛾00 + 𝛾01 𝑀𝐸𝐴𝑁_𝑉𝑂𝐶𝑗 + TREAT𝑗 + COVARIATE𝑗 + 𝑢𝑗 Academic Vocabulary Model B With co variates Academic Vocabulary 0.837*** 0.840*** (0.097) (0.145) 0.697*** 0.697*** (0.024) 1.264* (0.500) 3.397 (1.757) (0.024) 1.551** (0.501) 4.581 (4.342) 28.29*** 28.24*** Model A Outcome Academic Vocabulary Teaching Team Mean Academic Vocabulary Teaching Team Mean Centered Treatment Intercept Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) (0.517) Residual 1.775 (0.313) N 1554 -2LL 9654.227 Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (0.516) 1.555 (0.283) 1554 9647.524 HLM Predicting Student Knowledge of Academic Words Outcome Gates MacGinitie Vocabulary Teaching Team Mean Gates MacGinitie Vocabulary Teaching Team Mean Centered Treatment Intercept Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) Residual N -2LL Model C Model D With Covariates Gates MacGinitie Vocabulary Gates MacGinitie Vocabulary 0.691*** 0.580*** (0.070) (0.086) 0.798*** 0.798*** (0.022) 0.0151 (2.323) 160.9*** (34.920) (0.022) -0.373 (2.167) 235.2*** (43.480) 530.7*** 530.7*** (10.180) 40.88*** (6.785) 1416 12956.545 (10.180) 27.25*** (5.360) 1416 12944.513 Standard errors in parentheses HLM Predicting Student knowledge of Gates Vocab RQ3 Did improved classroom discussion mediate the impact of the Word Generation program on students’ academic vocabulary knowledge? c prime path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.700*** (0.024) 1.633** (0.530) a path Composite Discussion Quality Rating 0.138*** (0.031) 0.396* (0.167) Intercept 5.812*** (0.567) -2.789*** (0.567) Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) 2.108* 1.775 (0.375) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 (0.334) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 Outcome Academic Vocabulary (Pre) Treatment Composite Discussion Score Residual N 1446 b path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.696*** (0.024) 1.271* (0.560) 0.533 (0.376) 6.090*** (0.586) c prime path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.700*** (0.024) 1.633** (0.530) a path Composite Discussion Quality Rating 0.138*** (0.031) 0.396* (0.167) Intercept 5.812*** (0.567) -2.789*** (0.567) Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) 2.108* 1.775 (0.375) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 (0.334) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 Outcome Academic Vocabulary (Pre) Treatment Composite Discussion Score Residual N 1446 b path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.696*** (0.024) 1.271* (0.560) 0.533 (0.376) 6.090*** (0.586) c prime path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.700*** (0.024) 1.633** (0.530) a path Composite Discussion Quality Rating 0.138*** (0.031) 0.396* (0.167) Intercept 5.812*** (0.567) -2.789*** (0.567) Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) 2.108* 1.775 (0.375) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 (0.334) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 Outcome Academic Vocabulary (Pre) Treatment Composite Discussion Score Residual N 1446 b path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.696*** (0.024) 1.271* (0.560) 0.533 (0.376) 6.090*** (0.586) c prime path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.700*** (0.024) 1.633** (0.530) a path Composite Discussion Quality Rating 0.138*** (0.031) 0.396* (0.167) Intercept 5.812*** (0.567) -2.789*** (0.567) Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) 2.108* 1.775 (0.375) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 (0.334) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 Outcome Academic Vocabulary (Pre) Treatment Composite Discussion Score Residual N 1446 b path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.696*** (0.024) 1.271* (0.560) 0.533 (0.376) 6.090*** (0.586) c prime path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.700*** (0.024) 1.633** (0.530) a path Composite Discussion Quality Rating 0.138*** (0.031) 0.396* (0.167) Intercept 5.812*** (0.567) -2.789*** (0.567) Level 2 Variance (Teaching Team) 2.108* 1.775 (0.375) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 (0.334) 28.38*** (0.538) 1446 Outcome Academic Vocabulary (Pre) Treatment Composite Discussion Score Residual N 1446 b path Academic Vocabulary (Post) 0.696*** (0.024) 1.271* (0.560) 0.533 (0.376) 6.090*** (0.586) Multilevel Mediation Model 𝑫𝒊𝒔𝒄𝒖𝒔𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏𝒋 𝑻𝑹𝑬𝑨𝑻𝒋 Multilevel Mediation Model 𝑫𝒊𝒔𝒄𝒖𝒔𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏𝒋 𝑻𝑹𝑬𝑨𝑻𝒋 1.633** 𝑽𝑶𝑪𝑨𝑩𝒊𝒋 Multilevel Mediation Model 𝑫𝒊𝒔𝒄𝒖𝒔𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏𝒋 𝑻𝑹𝑬𝑨𝑻𝒋 1.633** 𝑽𝑶𝑪𝑨𝑩𝒊𝒋 Multilevel Mediation Model 𝑫𝒊𝒔𝒄𝒖𝒔𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏𝒋 𝑻𝑹𝑬𝑨𝑻𝒋 1.633** 𝑽𝑶𝑪𝑨𝑩𝒊𝒋 indirect effect = .396*.533 = .211 total effect = indirect effect + direct effect = 0.211 + 1.28 = 1.48 Bootstrapping Coefficient Standard Error z p value 95% Confidence Interval Indirect Effect 0.21 0.10 2.22 0.03 0.02 0.40 Direct Effect 1.28 0.31 4.06 > 0.001 0.66 1.90 Total Effect 1.49 0.30 4.99 > 0.001 0.90 2.07 command: ml_mediation, dv(WGV_TCTR_W2) iv(TREAT) mv(wrub_tot_SM_Y1) cv(WGV_TCTR) l2id(unit) Conclusions Changes in curricular materials can improve discussion. A free, low “implementation cost” program can have credible effects. The proportion of total effect of Word Generation mediated through improved discussion is 0.14. Limitation and questions How can we further improve discussion? Does improved discussion transfer? What are the other effective pathways for student learning from WG? Patterns of Students’ Vocabulary Improvement from One-time Instruction and Review Instruction Wenliang He, Joshua Lawrence (University of California, Irvine) Emily Galloway, Claire White, Catherine Snow (Harvard University) Judy Hsu (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) Background Vocabulary knowledge is positively correlated with reading skills. Prior research has focused on studies of factors that impact the learning of academic vocabulary (e.g. frequency, exposure, prior knowledge) and effective vocabulary intervention techniques (e.g. multimodal enhancement, active processing, mnemonics). Regardless of the importance and the prevalence of vocabulary instruction in schools, few classroom-based intervention studies have been conducted on learning the effect of review (second-time) instruction. Research Questions What factors predict students’ improvement in vocabulary knowledge from first-time instruction in the WG program? Can review (second-time instruction) significantly contribute to additional improvement in vocabulary knowledge to first-time instruction? Research Design Pre-test Review Post-test Group A Group B 151 students 159 students Right before program started 5 words/week 5 words/week for 7 weeks for 7 weeks 7 Yellow Words 7 Red Words 5 words/week 5 words/week for 4 weeks for 4 weeks By the end of the 12th week Research Design Overview of Yellow, Red and Core Instructional Words Count Word List Yellow Words Red Words 7 adequate (1) relevant (2) capacity (3) Contrast (4) assess (5) paralyzed (6) emphasize (7) 7 formulate (8) retain (9) distribute (10) logical (11) disproportionate (12) obtain (13) restrict (14) Core Instruction Words recite (15) cohesion (20) constrain (25) amended (30) generate (35) incentives (40) enable (45) 34 invasion conclusion components (16) (18) (17) equity documented interaction (22) (23) (21) eligible complex contaminated (26) (27) (28) apathy Concept maintained (32) (31) (33) enforced perceived perspective (37) (38) (36) amnesty acquired prescribed (43) (41) (42) excluded aptitude assumed (46) (47) (48) critical (19) altered (24) distinct (29) Attributes (34) conserve (39) proceeded (44) Analysis & Results (Q1) What factors predict students’ improvement in vocabulary knowledge from first-time instruction in the WG program? Correlations between Measures from One-time Instruction Data 1. Percent Correct in Pretest 2. Percent Correct in Posttest 3. Word Frequency 4. Week of Instruction 5. Improvement 1 2 3 4 1 0.90*** 1 0.34* 0.30* 1 -0.02 -0.04 0.09 1 -0.23 0.2 -0.09 -0.03 (p=0.11) (p=0.17) (p=0.53) (p=0.86) 5 1 Note. * p < .05. *** p < .001. (two-tailed t-tests) Percent Correct is the percentage of students who are correct in a multiple choice question, testing on a specific word in either pre or post test. Analysis & Results (Q1) Percent Correct at Pretest (%) 0 ≦ P+ ≦ 100 Below Average Above Average Detailed Breakdown 10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-60 60-70 70-80 80-90 Word Count 48 26 22 Mean Percent Improvement (%) 10.59 11.06 10.04 SD (%) 8.56 10.61 5.43 Min (%) -4.77 -4.77 0.59 Max (%) 46.00 46.00 20.16 4 5 7 11 9 4 5 3 18.37 11.60 7.11 11.49 12.40 8.63 8.83 3.46 19.35 13.43 3.14 8.17 3.92 6.55 3.74 2.57 0.89 -4.77 3.22 -0.16 5.01 1.10 5.76 0.59 46.00 30.85 12.56 22.65 17.21 16.29 14.70 5.56 50 Analysis & Results (Q1) 40 41 amnesty 10 20 30 contrast 0 20 18 21 capacities restricted 27 34 32 disproportionately 46 relevant 40 adequate 35 28 assess 25 43 45 3848 26 2433 paralyzed 23 17 42 30 37 47 emphasized 15 19 36 retain 29 16 distribute logical 4439 22 formulated obtain 31 10 20 . 30 40 50 60 70 Percentage of Students Correct at Pretest Yellow Words Red Words 80 90 Fitted values Analysis & Results (Q1) Improvement for words with above average difficulties 20 β = -0.61, p < 0.01 capacities eligible attributes maintained excluded relevant 15 prescribed assumed perspective 10 conclusion enable distribute contaminated acquired 5 perceived logical proceeded conserve retain obtain 0 50 60 documented formulated 70 80 Percentage of Students Correct at Pretest Fitted values 90 Analysis & Results (Q1) Improvement for words with below average difficulties 50 amnesty β = -0.20, p = 0.32 40 contrast 30 components equity 20 incentives adequate disproportionately constrain 10 interaction emphasized cohesion 0 restricted generate complex assess altered concept paralyzed invasion amended aptitude recite critical enforced distinct apathy 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 Percentage of Students Correct at Pretest Fitted values 45 50 Analysis & Results (Q2) Can review significantly contribute to additional improvement in vocabulary knowledge to first-time instruction? 35 Instruction 30 25 Review Instruction 20 Review 15 10 5 0 Red Words Yellow Words Group A Group B Analysis & Results (Q2) Overview of Review Impacts by Word Groups Word Groups Word Count Review Impact (%) S.E.(%) p (two-tailed) All Words 14 2.58 1.71 0.16 Hard Words 7 -1.36 2.32 0.58 Easy Words 7 6.51 1.47 0.004 Words below the 48% cut-off were recoded as Hard Words, and those above were recoded as Easy Words. Conclusion The effects of one-time instruction and review instruction depend on students’ prior word knowledge, reflected by the percentage of student correct at pretest. For moderately difficult words, i.e. percent correct values greater than 48% in this study, improvement from one-time instruction is stronger for harder words than for easier words. However, if words are exceedingly difficulty, none of the measure in this study can effectively predict improvement from one-time instruction. Conclusion Review instruction is most effective (p = 0.004) when students are reasonably familiar with the words, i.e. percent correct values greater than 48%. In this case, review contributes an extra 6.51% improvement compared with the 10.04% improvement from firsttime instruction. Learning overly unfamiliar words twice, however, does not have any statistically significant effect over one-time instruction (p = 0.58). Implications This study indicates that (a) effects of vocabulary instruction is most predictable with Goldilocks words, as students do not benefit as much with either overly simple or exceedingly hard words; (b) prior knowledge is crucial in explicit vocabulary instruction (c) teaching difficult words may necessitate more effective instruction techniques. Thank You Engaging Middle School Students in Classroom Discussion of Controversial Issues Alex Lin Dr. Joshua Lawrence Civic engagement Declining voting turnout Declining rate of civic knowledge Importance of stimulating news media use and political discussion at home Discussion of Controversial Issues One way of improving civic knowledge is using controversial issues as topics for classroom discussion McDevitt and Chaffee (2000) found that enrollment in Kids Vote was positively related to students’ habit of initiating political discussion at home Hess and Posselt (2002) found that enrollment in the Public Issues was related to students making 70% more contributions in classroom discussion. What about middle school students? Program Features In the Word Generation program: Students are exposed to daily discussions of controversial topics Different topic each week Students take a position on an issue Teacher facilitates classroom debate Breakdown of Controversial Topics (Year 1 and Year 2) in Two Years of WG Program Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 YEAR 1 TAUGHT - Should colleges use Affirmative Action? Should the government fund stem cell research? Should Creation be taught in school? Should English be the official language of the United States? Is nuclear power a danger to society? (Fall 2010 – Spring 2011) YEAR 2 TAUGHT - Should there be more strict dress codes at schools? Is the death penalty justified? Does rap music have a negative impact on students? What should be done about global warming? Should the government allow animal testing? NON-TAUGHT TOPICS - Should schools protect students from cyberbullying? Should schools be a place for debates? Should secret wiretapping be legal? Should schools have a vocational track? (Fall 2011 – Spring 2012) Research Questions: (1) In the First Year Sample (6th Graders only) How do students enrolled in Word Generation compare with control students, in terms of their confidence to participate in a discussion of controversial topics? (2) In the Second Year Sample (7th and 8th Graders) How do students enrolled in Word Generation compare with control students, in terms of their confidence to participate in a discussion of controversial topics? Methods Surveys administered in May 2012 (2nd year of the study) Students were assessed the question: How confident are you in being able to participate in a discussion about the following topics? - 14 topic questions from the year 1, year 2 and non-taught topics - Students responded about their discussion confidence level from (1) “not at all” to (5) “extremely” Methods: Participants Grade Level Contributions by Schools Word Generation Control TOTAL 6 7 8 TOTAL 1,163 1,167 1,121 3,430 617 482 694 1,793 1,780 1,649 1,815 5,223 Analysis Plan For each sample (6th) and (7th + 8th) graders: Compare discussion confidence levels on the 14 controversial topics between students enrolled in the WG program and control groups Compare discussion confidence levels between students enrolled in the WG program with control groups on TAUGHT and NON-TAUGHT topics Confidence to Discuss Comparison by Schools (6th Grade Sample) Results 4.00 4.12 4.10 3.88 3.67 3.50 Confidence to Participate in Discussion 3.31 3.26 3.15 3.19 3.00 3.27 2.95 2.80 2.50 2.62 2.56 2.53 2.56 2.40 2.28 2.00 1.99 2.86 2.84 2.73 2.68 2.76 2.69 2.40 2.35 2.36 2.06 1.50 TAUGHT Control School WG School NON-TAUGHT Control School WG School Results 1st Year Students: Comparison of Students’ Self-Reports on Discussion Confidence Level Between Schools Confidence to Participate in Discussion 3.00 0.01 t(1857)= -0.41, ns 2.94 0.13 *** 2.95 t(1850)= -3.41, p < 0.001 2.75 2.72 2.50 2.59 2.25 2.00 CONTROL WORD CONTROL WORD GENERATION GENERATION Taught Effect size: (sd=.82) = 0.16 Non-taught TAUGHT Control School WG School NON-TAUGHT Control School WG School Confidence to Participate in Discussion Comparison (7th & 8th Graders) Results 4.00 3.82 3.82 3.66 3.69 3.50 Confidence to Participate in Discussion 3.00 3.13 2.98 2.64 2.50 2.72 2.69 2.71 2.47 2.36 2.00 2.21 2.46 2.30 3.01 3.11 3.03 3.09 3.18 2.79 2.76 2.68 2.55 2.33 2.37 2.03 1.50 TAUGHT Control School WG School NON-TAUGHT Control School WG School 2.70 Results 2nd Year Students: Comparison of Students’ Self-Reports on Discussion Confidence Level Between Schools Confidence to Participate in Discussion 3.00 0.08 *** 0.02 t(3615)= -3.47, p < 0.001 t(1200)= -10.93, ns 2.84 2.75 2.88 2.90 CONTROL WORD GENERATION 2.76 2.50 2.25 2.00 CONTROL WORD GENERATION Taught Effect size: (sd=0.70) 0.11 TAUGHT Control School WG School Non-taught NON-TAUGHT Control School WG School Results How do students enrolled in Word Generation compare with control students, in terms of their confidence to participate in classroom discussion of controversial topics? In both (6th grade) and (7th + 8th grade) samples, students in the Word Generation program report more confidence in being able to have a classroom discussion of controversial topics that are covered in class Discussion Consistent with past studies that curricular exposure to controversial topics can improve students’ confidence to participate in discussion Students’ abilities to participate effectively in discussion of controversial issues can improve as a result of being enrolled in a course that places primacy on such discussions (Hess & Posselt, 2002) Young people draw more attention to news information when that information is perceived to be useful for school assignments and peer conversations (Atkin, 1981; Kanihan & Chaffee, 1996; McDevitt and Chaffee (2000) . Future Work - Examine students’ perception of openness in classroom discussion - Freedom to disagree in class - Teacher’s skill in facilitating discussion - Compare students’ perception of openness in classroom discussion between WG and CO schools - Student level - Classroom level - Examine students’ habit of extending discussion of controversial issues outside of home and their news media use (newspaper and Internet) . Works Cited Atkin, C. (1972). Anticipated communication and mass media information seeking. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 188-199. Hess, D., & Posselt, J. (2002). How high school students experience and learn from the discussion of controversial public issues. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 17(4), 283-314. Kanihan, S., & Chaffee, S. H. (1996). Situational influence of political involvement on information seeking: A field experiment. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Anaheim, CA McDevitt, M., & Chaffee, S. (2000). Closing gaps in political communication and knowledge effects of a school intervention. Communication Research, 27(3), 259-292. Appendix 1ST Year Students: Comparison of Students' Discussion Ability Between Schools (6th Graders) Non-taught 2.95 -0.23 *** Taught 2.72 t(1200)= -10.93, p < 0.001 Non-taught 2.94 -0.35 *** t(650)= -12.22, p < 0.001 Taught 2.59 2.00 2.25 2.50 2.75 Confidence to Participate in Classroom Discussion 3.00 Results 2ND Year Students: Comparison of Students' Discussion Ability Between Schools (7th & 8th Graders) Non-taught 2.90 -0.06 *** t(2319)= -15.20 p < 0.001 Taught 2.84 Non-taught 2.88 -0.12 *** t(1283)= -15.20, p < 0.001 Taught 2.76 2.00 2.25 2.50 2.75 Confidence to Participate in Classroom Discussion 3.00 Heterogeneous Effects of Word Generation on Students with Differing Levels of English Proficiency Jin Kyoung Hwang, Joshua Lawrence (University of California, Irvine) Elaine Mo (University of the Pacific) Patrick Hurley (Strategic Education Research Partnership) Language Minority (LM) Learners • School-aged students in the US who hear and/or speak a language other than English at home (August & Shanahan, 2006) • Large population • Over 11 million students, about 5 million are classified as limited English proficient (Aud et al., 2012) • Largest growth • One of the fastest growing groups among the school-aged population in the U.S. (Aud et al., 2011) Language Minority (LM) Learners • Differing Levels of English Proficiency • Initially fluent English proficient (IFEP) • Students with full English proficiency by the time they enter school • Limited English proficient (LEP) • Students who still need English language support • Redesignated fluent English proficient (RFEP) • Students who used to be LEP but attained sufficient English proficiency to be reclassified Vocabulary Intervention & LM Learners • Quasi-experiments of WG (Lawrence, Capotosto, Branum-Martin, White, & Snow, 2012; Snow, Lawrence, & White, 2009) • • • Vocabulary Improvement Program (Carlo et al., 2004) • • No language by treatment interaction Quality English and Science Teaching (August et al., 2009) • • ELLs in treatment schools improved more than EO students on polysemy task Improving Comprehension Online (Proctor et al., 2009/2011) • • LM students with full English proficiency benefitted more LM students with limited English proficiency did not No language by treatment interaction Language Workshop (Townsend & Collins, 2009) • All participants were Spanish-English speakers Research Questions • Is there a heterogeneous effect of Word Generation for EO, IFEP, and RFEP students? • Is there a heterogeneous effect of Word Generation for RFEP students according to the number of years they have been redesignated? Methods: Participants • • • 13 middle schools: 7 treatment & 6 control N = 6,193 students Language Status • • • • • Initially Fluent English Proficient (IFEP, n = 632) Redesignated Fluent English Proficient (RFEP, n = 2,515) Limited English Proficient (LEP, n = 1,011) English only (EO, n = 2,035) Years since Redesignation • • • • 0-1 year: n = 419 1-2 years: n = 754 2-3 years: n = 419 > 3 years: n = 661 Methods: Measures • Dependent Variable: • Academic Vocabulary • Word Generation Vocabulary Posttest (50 items total; 40 items were taught throughout the program) • Independent Variables: • • • • Intervention Language Proficiency Groups (EO, IFEP, RFEP; RQ1) Years since Redesignation (for RFEP students only; RQ2) Academic Vocabulary • Word Generation Vocabulary Pretest (School mean & School centered mean) • Reading Comprehension • Gates-MacGinitie Comprehension Test (School mean & School centered mean) • Grade Level • School of Attendance • Gifted and Talented & Special Education Methods: Analysis Plan RQ 1: Heterogeneous Effect of WG for EO, IFEP, and RFEP students? RQ1: Heterogeneous Effect of WG for EO, IFEP, and RFEP students? Academic Vocabulary: WG Posttest 29 28.5 28 27.5 27 26.5 Treatment Control 26 25.5 25 24.5 24 EO IFEP RFEP Language Proficiency Groups RQ2: Heterogeneous Effects of WG within RFEP students? Academic Vocabulary: WG Posttest RQ2: RFEP Students with Different Years since Redesignation 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 Treatment Control 0-1 years 1-2 years 2-3 years >3 years Years since Redesignation Conclusion • Heterogeneous effects of Word Generation • Replicated and extended findings from previous Word Generation studies • RFEP students are a heterogenous group References Aud, S., Hussar, W., Kena, G., Bianco, K., Frohlich, L., Kemp, J., Tahan, K. (2011). The Condition of Education 2011 (NCES 2011-033). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Aud, S., Hussar, W., Johnson, F., Kana, G., Roth, E., Manning, E., . . . Zhang, J. (2012). The Condition of Education 2012 (NCES 2012-045). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on language minority chidren and youth. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. August, D., Branum-Martin, L., Cardenas-Hagan, E., & Francis, D.J. (2009). The impact of an instructional intervention on the science and language learning of middle grade English language learners. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 2(4), 345-376. References Carlo, M.S., August, D., McLaughlin, B., Snow, C.E., Dressler, C., Lippman, D.N., . . . White, C.E. (2004). Closing the gap: Addressing the vocabulary needs of English language learners in bilingual and mainstream classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(2), 188-215. Kieffer, M.J. (2008). Catching up or falling behind? Initial English proficiency, concentrated poverty, and the reading growth of language minority learners in the United States. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 851-868. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.4.851 Lawrence, J., Capotosto, L., Branum-Martin, L., White, C., & Snow, C. (2012). Language proficiency, home-language status, and English vocabulary development: A longitudinal follow-up of the Word Generation program. Unpublished manuscript, Harvard University. Proctor, C.P., Dalton, B., Uccelli, P., Biancarosa, G., Mo, E., Snow, C., & Neugebauer, S. (2011). Improving comprehension online: Effects of deep vocabulary instruction with bilingual and monolingual fifth graders. Reading and Writing, 24(5), 517-544. Townsend, D., & Collins, P. (2009). Academic vocabulary and middle school English learners: An intervention study. Reading and Writing, 22(9), 993-1019.