Aeschylus - E28B: The Power to "Act"

advertisement

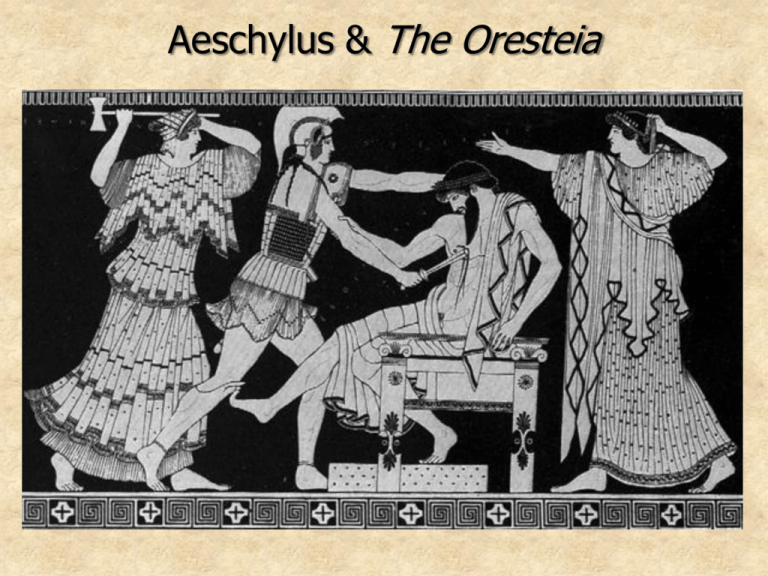

Aeschylus & The Oresteia Aeschylus: c.525-455 B.C. • Born in Eleusis (near Athens) to a wealthy family • Fought against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C. –and at Salamis ten years later • Reputed to be the first playwright to introduce a second actor • Won his first victory at the Dionysia in 484 B.C., when he was about 40 years old • Often wrote trilogies, plays intended to be performed as connected chapters at a single Dionysia • The Oresteia is generally considered Aeschylus’ greatest and final entry in the Dionysia; the plays (the only surviving ancient Greek trilogy) were originally paired with a satyr piece, Proteus The (Cursed) House of Atreus The Oresteia: Agamemnon • Agamemnon returns to Argos after winning the Trojan War, carrying the prophetess Cassandra as a prize. • Clytemnestra greets him, proclaims her fidelity, and announces that she has sent Orestes to another city-state to keep him safe. • Clytemnestra convinces Agamemnon to enter his house by walking upon crimson tapestries; this is an impious act, since only the gods should be allowed to do so. • Cassandra foresees her own death, but also eventually enters the house • Clytemnestra murders Agamemnon after his bath, then murders Cassandra • Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, assume rule of Argos The Oresteia: The Libation Bearers CONTEXT • Orestes has returned to Argos from exile, accompanied by his companion, Pylades. • The Oracle of Apollo has commanded Orestes to avenge his father’s death. • Clytemnestra has asked Electra to pour libations (a mixture of wine, grain, and olive oil) upon Agamemnon’s tomb. • The Greek chorus in this play is (remarkably) represented as a number of slave women—high-born women who were taken after the siege of Troy. “We must suffer, suffer into truth.” --Agamemnon Chorus The Libation Bearers: Study Questions 1) Does Orestes have agency? In other words, does he determine his own actions, or are his actions chosen for him by others? How does Aeschylus depict the relationships between the individual and gods/ society—and how might that relate to his larger rhetorical goals? 2) In what way(s) does The Libation Bearers—or the Oresteia as a whole— adhere to the later Aristotelian definition of tragedy? In what way(s) does it depart from Aristotle’s “rules”? What is the significance of the ways in which The Libation Bearers seems to follow or break from the tragic genre? 3) What is justice? How is it variously interpreted by different characters, and how do their visions of justice affect their actions? What does Aeschylus ultimately suggest about the nature of justice? 4) The Libation Bearers features a significant number of female characters, who are portrayed with varying, complex characteristics: the Chorus, Electra, Cilissa, and Clytemnestra. What does Aeschylus imply about ideal Greek womanhood? What feminine qualities seem to receive Aeschylus’ approval—and why?