Acute Liver Failure - Institute for Health Policy

advertisement

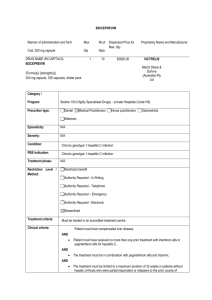

Acute Liver Failure Definition The development of prolonged prothrombin time and encephalopathy within 8 weeks of symptom onset in patient with no previous liver disease U.S. annual incidence about 2,000 cases per year (1) High mortality Causes of Acute Liver Failure Varies by geographic region In the U.S., acetaminophen hepatotoxicity most common Indeterminate cause Idiosyncratic drug reactions – Isoniazid most common Causes of ALF Hepatitis B – U.S. 4th most common cause; world wide # 1 cause Hepatitis A – endemic areas Autoimmune hepatitis Ischemia Wilson’s Disease Causes of ALF Budd Chiari Syndrome Pregnancy – acute fatty liver of pregnancy and the HELP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver chemistries, low platelets) Transplant-free Survival Highest in APAP hepatotoxicity Followed by drug reaction Followed by indeterminate cause Best when ALF develops hyper acutely i.e., within seven days The Phenomenon Highly unpredictable Dramatic Requires aggressive intensive care management, anticipation of complications, and evaluation/listing for liver transplantation Survival Correlates with degree of encephalopathy and coagulopathy Encephalopathy may be abrupt and rapidly progressive – Subtle mood change - > seizures - > obtunded - > decorticate posture – Associated with cerebral edema rather than portosystemic shunting of toxins seen in cirrhosis Acetaminophen Overdose Accidental Suicide gesture/attempt Emergency Room administration of antidote: p.o. NAC or I.V. Acetadote (contraindicated in sulfa allergy) Accidental Overdose High dose APAP for an extended period Inadvertent simultaneous administration of APAP w/ combination drugs: – OTC Sinus and cold preparations – OTC Narcotic pain relievers – OTC Sleep preparations – In combination w/ alcohol Pathophysiology Dose dependent; known liver toxin Also influenced by the presence of malnutrition, concomitant ethanol, co-administered drugs, and CYP 384 polymorphisms Centrilobular necrosis without inflammation Signs and Symptoms Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, malaise, right upper quadrant discomfort Dark urine, pale stool, icterus Transaminases rise within 10 – 12 hours, often to dramatic levels AST > ALT, peak at day three and rapidly improve Jaundice develops quickly, total bilirubin not as high as that seen in other causes of ALF Case Study Questions and Answers Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension The Final Stage of Chronic Liver Disease Due to Any Cause Cirrhosis Excess extracellular matrix/fibrosis in liver Fibrosis spans portal-central areas – portal-portal or central-central also seen Fibrosis encases groups of hepatocytes Results in distorted architecture and vasculature Normal Cirrhosis Nodules surrounded by fibrous tissue GROSS IMAGE OF A CIRRHOTIC LIVER Cirrhotic liver Nodular, irregular surface Nodules Portal Hypertension • • • • Cirrhosis - > increased resistance to flow of blood in sinuosoids and in liver Increased resistance = increased portal pressure = portal hypertension Pressure in PV causes release of vasodilators, i.e., nitric oxide (NO) NO causes splanchnic arteriolar vasodilation and increased splanchnic inflow of blood This increased flow maintains portal hypertension in spite of development of low resistance collaterals SINUSOIDAL PORTAL HYPERTENSION Sinusoidal Portal Hypertension Cirrhotic liver Portal vein Portal systemic collaterals Consequences of Portal Hypertension Splenomegaly – Thrombocytopenia – Palpable spleen; splenectomy harmful Varices – On imaging may be peri-gastric, esophageal, or splenic – On gastroscopy of variable size – Risk for bleed increases w/ advancing liver failure – Treat w/ nonselective beta blocker, banding Consequences of Portal Hypertension Ascites: The accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity – An important clue to the presence of advanced cirrhosis – Result of sinusoidal HTN caused by blocked hepatic venous outflow 2/2 regenerative nodules and fibrosis – Result of plasma volume expansion, sodium, and water retention Serum to Ascites Albumin Gradient “SAAG” The concentration of ascitic fluid protein is much lower than the concentration of serum protein This is due to sinusoidal capillarization, decreased permeability to plasma proteins Protein concentration in ascitic fluid in cirrhosis correlates inversely w/ the degree of portal hypertension Ascites Associated conditions: – Hyponatremia – Umbilical hernia – Hepatic hydrothorax Complication of ascites: – Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis – Pneumococus common etiology – Gram negative bacteria Ascites Treatment: – Sodium restriction, diuretics, paracentesis – Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt TIPS often worsens encephalopathy Prognosis: continuum of uncomplicated ascites - > refractory ascites - > hepatorenal syndrome Mortality approximately 20%/year THE TRANSJUGULAR INTRAHEPATIC PORTOSYSTEMIC SHUNT Hepatic vein TIP S Portal vein Splenic vein Superior mesenteric vein Consequences of Portal Hypertension Hepatic encephalopathy Episodic vs persistent Usually precipitated by events such as: – Bleeding – Infection – Use of sedatives or hypnotics – Dehydration Hepatic Encephalopathy Pathogenesis: failure of the liver to detoxify portal blood toxins in the setting of decreased hepatic function and/or diminished hepatic perfusion by portal blood. Cerebral edema, ammonia, and disturbances in cell function, esp. astrocytes Diagnosis: don’t assume it is HE until other potential causes of altered mental status have been considered Encephalopathy Alternative Explanations Metabolic: hypoxia, hypoglycemia, hypo/hypernatremia, thyroid disease, hypercalcemia Central Nervous System: CVA, Subdural hematoma, post ictal state, metastatic cancer Toxins: alcohol, CNS depressants Infection: sepsis, meningitis, encephalitis, delerium tremens Staging West Haven Criteria Stage 0: No abnormality Stage 1: Trivial lack of awareness – Shortened attention span – Euphoria or anxiety – Impairment of addition and subtraction Stage 2: Lethargy – Time disorientation – Personality change – Inappropriate behavior Staging Hepatic Encephalopathy West Haven Criteria Stage 3: Somnolence to semistupor – Response to stimuli – Confusion – Disorientation – Bizarre behavior Stage 4: Coma Generalized motor abnormalities common: hyperreflexia, asterixis, Babinski + Hepatic Encephalopathy Blood ammonia testing has little role in the diagnosis of HE Clinical suspicion is the main guide Treatment: – Supportive care for altered mental state – Identify and treat the precipitating cause – Exclude and/or treat other medical illnesses – Begin empirical therapy: lactulose, nonabsorbable antibiotics, metronidazole Complications of Cirrhosis Osteoporosis Increased risk of infections Muscle cramps Increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma Malnutrition Depression Pruritis Standard Recommendations for All Cirrhotics Vaccinate against viral hepatitis, pneumococcal pneumonia, influenza Baseline bone density test – treat osteopenia or osteoporosis as indicated Baseline ultrasound and AFP and repeat semi-annually for HCC surveillance if cirrhotic Esophageal varix surveillance – treat as indicated Standard Recommendations for All Cirrhotics Refer for liver transplantation Monitor for signs of advancing liver failure Avoid alcohol Avoid NSAIDs Acetaminophen is analgesic of choice If significant ascites, cane, walker If Grade II or higher encephalopathy take the car keys, protect from harm Case Study Hepatitis C Prototype Chronic Liver Disease History of Viral Hepatitis 2000 B.C. 1st recorded hepatitis epidemic 1963 Australia antigen AKA Hepatitis B surface antigen (Blumberg & Alter) 1970 Hepatitis B 1972 National Blood Policy requires testing of blood donors for HBsAg History of Viral Hepatitis 1973 Hepatitis A (Feinstone, Kapikian & Purcell) 1975 “Non-A Non-B Hepatitis” 1977 Hepatitis D (Rizzetto & Gerin) 1983 Hepatitis E (Balayan) 1989 Hepatitis C (Alter, et al. & Chiron Corp) Disease Burden Estimates Center for Hepatitis C, Cornell University HIV US Chronic Infection HBV HCV 1.0 million 1-1.25 million 3-4 million* New Infection/year 40,000 50,000* 20-30,000 Deaths/year 16,000* 3,000-5,000 10,000 – 12,000 40 million 350 million* 1/3 world population 170 million New Infection/year 4 million 65 million* 3-4 million Deaths/year 3 million* 0.5 – 1.2 million >250,000 Worldwide Chronic Infection Hepatitis C Prevalence Estimates Affects both genders, all ages, races and regions of the world: 170 million or 3% world population 40% of all chronic liver disease in U.S. Most common blood-borne infection in the U.S.: 1.8% of population – 5.2 million HCV antibody positive, 4.1 million HCV RNA+ – 1.1 million = homeless, incarcerated, institutionalized, undocumented, and military – U.S. prisons estimates: 600,000 HCV RNA+ 25% - 40% of prison population 30% released each year (high risk behavior perpetuates transmission) – Born between 1945 and 1964, now age 55-64, have highest mortality Estimated Incidence of Acute HCV Infection United States, 1960-2001 New Infections/100,000 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 Year Hepatitis C Facts HCV related deaths increased 123% between 1995-2004 (Wise, et al.) – 1.09 deaths per 100,000 in 1995 – 2.44 deaths per 100,000 in 2004 – In 2004: 7,427 deaths, male 2.5 x > female – Middle-aged cohort 45 y/o to 64 y/o Male Hispanic, AA, NA, Alaska natives – African American males 9% w/ HCV-1 Hepatitis C Facts Less than 10% of infected are being treated Most do not know they are infected 85% of HCV positive individuals can be identified by testing 20-59 year olds with elevated ALT and history of IDU or blood transfusion before 1992 Those infected for 20 – 30 years – 10% - 20% -> cirrhosis – 1% - 5% -> hepatocellular carcinoma Who to Screen Ever injected drugs Clotting factors before 1972 Received organ before 1992 Ever on dialysis Children of infected mothers Evidence of liver disease Workers after needle stick injury Who Not to Screen Non-sexual household contacts Healthcare workers, emergency medical workers, public safety workers Pregnant women If have contraindication to treatment If have limited life expectancy Hepatitis C Virus An enveloped, single-stranded, RNA virus with a genome of about 9,600 nucleotides (1 pentose sugar, 1 base + phosphoric acid = structural unit of nucleic acids i.e., RNA and DNA) Flaviviridae family; other viruses in the family include West Nile virus; others cause yellow fever, dengue Hepatitis C Virus Viral replication 1011 to 1012 virion/day (trillions!) No proof reading ability -> high rate of mutation helps it to escape the immune system -> difficult to eradicate Genotype: Genetic Sequence Used to project response to treatment Six types, multiple subtypes Hepatitis C Around the World 1: 60% U.S. cases; (Europe, Turkey, Japan) 2: 10% - 15% U.S. cases; wide distribution 3: 4% to 6% U.S. cases (India, Pakistan, Australia, Scotland) 4: < 5% (Middle East, Africa) 5: < 5% (South America) 6: < 5% (Hong Kong, Morocco) Following Exposure Two weeks: HCV RNA detectable Between weeks 2-4: ALT elevated with spike by week 6 6-7 weeks: Anti-HCV/HCV Antibody detectable Routes of Transmission Percutaneous Permucosal Household Percutaneous Exposure Highest users rate is among injecting drug – 80%-90% of cases Recipients of clotting factors prior to 1987 (before virus inactivation) Hemophiliacs Blood transfusion, transplant prior to 1992 Percutaneous Exposure Contaminated equipment, unsafe injection practices – Hemodialysis, plasmapheresis, phlebotomy – Multiple dose injection vials – Las Vegas, NV 2008 – Therapeutic injections Treatment of schistosomiasis in Egypt Percutaneous Exposure Occupational Exposure – Needle stick with hollow bore needles – Incidence 1.8% with exposure to HCV+ source – 10 X lower than from HBV + source – Case reports: transmission from blood splash to eye – Prevalence 1-2% among health care workers (same as general population) Peter Gulick D.O., Rule of Three’s Risk of viral transmission following occupational needle stick injury: – 30% hepatitis B – 3% hepatitis C – .3% HIV Post-Hepatitis C Exposure Test source for HCV Antibody (anti-HCV) If positive, test worker – No post exposure IgG or anti-viral Rx – ALT and anti-HCV at baseline and 4 – 6 months – For earlier diagnosis, HCV RNA by PCR 4 – 6 weeks – Confirm all anti-HCV + result w/ RIBA – Refer infected worker to specialist for medical evaluation and management Route of Transmission Permucosal Inefficient Perinatally: 5% risk – Higher if woman co-infected with HIV – No association with delivery method/breast feeding – Infected infants: If test for anti-HCV at birth will be positive due to placental transfer; best to test for HCV RNA 3rd or 4th month; often clear by two years, others develop CHC; refer to pediatric specialist Permucosal - Inefficient Sexual: 1.5% in monogamous relationships Accounts for 15% - 20% of acute and chronic infections in U.S. Factors that facilitate transmission unknown Infected partner, multiple partners, early sex, non use of condoms, other STDs, sex with trauma MSM no higher risk than heterosexuals Partner studies report low prevalence (1.5%) among long term partners Route of Transmission Household Contact Rare – Could occur through percutaneous or mucosal exposures to blood Sharing personal hygiene items Contaminated equipment used for home injections, folk remedies, cultural practices such as scarification, circumcision, tattooing Natural History Clinical spectrum is variable and disease progression is unpredictable. Majority develop chronic hepatitis C: HCV Ab+, RNA by PCR+ – Mild - majority – Moderate – Severe Natural History Acute Hepatitis C Frequently asymptomatic Symptoms: malaise, asthenia, anorexia, right upper quadrant discomfort, pruritis, less common jaundice (25%), intermittent nausea, vomiting. 1/6 seek medical attention Usually resolves in 12 weeks Rates of spontaneous clearance between 15% to 45% Loss of virus between 6 and 24 months Factors Influencing Progression Host Virus Factors Factors Environment Factors Influencing Progression Host Factors – Age at infection: 40 y/o and older, more severe disease – Male gender: less likely to clear virus – Obesity/Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease – Immune system status – ? Genetic susceptibility Factors Influencing Progression Viral Factors – Co-infection with HBV, HIV – Duration Transfusion related CHC leads to more aggressive disease (CABG age 50, time to cirrhosis 14.7 years) IDU age 40: 16 years to cirrhosis Less than age 50: 29.2 years to cirrhosis IDU age 21-30: 33 years to cirrhosis Factors Influencing Progression Environmental Factors – Alcohol consumption suppresses immune response hepatotoxic promotes fibrogenesis 50g/day men, 20g/day women – Antiviral Therapy – Iron – Genetic Hemochromatosis Natural History Chronic Hepatitis C Mild – infection 40 years or more with no or mild fibrosis Moderate – Severe cases progress to: – Cirrhosis – End Stage Liver Disease – Hepatocellular carcinoma – Liver transplantation – Death Chronic Hepatitis C Frequently no symptoms until development of advanced liver disease Fatigue, depression, cognitive changes (difficulty concentrating, memory impairment) Extra hepatic manifestations As Soon as Diagnosis Confirmed Immunize against hepatitis A and hepatitis B Advise patient to avoid alcohol Review all medications, including over the counter, vitamins, herbal remedies, and nutritional supplements for potential hepatotoxicity Teach transmission risk reduction strategies Barriers to Treatment Stigma – people unwilling to discuss Treatment options: toxic, costly, overall sustained virological response (SVR) 55% Access to care: collaborative approach should include PCP, specialist, case manager, qualified mental health provider, substance abuse trained provider No public funds for screening, surveillance, prevention programs, treatment, community- based needle exchange programs Barriers to Treatment Substance abusers mistrust authorities, unpredictable follow through, lack of experience w/ the healthcare system Provider: – – – – – – Inexperience, ignorance Unrealistic expectations, resource intense Negative attitude Frustration Moralize Patient blame History of HCV Treatments 1991: 1st generation was interferon alpha 1998: 2nd generation ribavirin added to interferon alpha (increased SVR from 16% to 41%*) – Virazole developed 1972 for influenza – Viramidine the pro-drug of ribavirin – RVN is a nucleoside analog 2001: 3rd generation pegylated interferon replaces interferon alpha Factors Influencing Response to Treatment Host Factors – – – – Race Steatosis, obesity Cirrhosis 10% to 12% lower rate of SVR Immunocompromised Virus Factors – Genotype – Viral load – Early viral kinetics Therapeutic – Presence of rapid virological response – Inadequate dosing – Non-compliance Goals of Therapy Viral Eradication: sustained virological response – Genotypes 1,4,6 45% SVR – Genotypes 2 & 3 70% to 85% SVR Improve Histology – Prevent decompensation – Reduce rates of HCC – Reduce need for transplantation – Prevent liver-related death Treatment Considerations Stage of liver disease Likelihood of SVR Co-morbidities Social support Presence of extra-hepatic manifestations Age, motivation Who is Eligible for Treatment? Any person infected with hepatitis C is a potential candidate The majority will not progress to cirrhosis and its complications: 20% will progress to cirrhosis in 20 years If no contraindications, treat genotypes 2 and 3 without liver biopsy Perform biopsy on genotype 1 Who is Eligible for Treatment? (cont’d) If no fibrosis may choose to delay Treatment often not urgent Patient should determine timing Contraindications to Treatment Uncontrolled or severe depression Active alcohol/substance abuse Decompensated liver disease Renal transplant Liver Biopsy Liver biopsy is to hepatitis C as CD4 count is to HIV Grade indicates the extent of necroinflammatory damage Stage indicates the cumulative fibrosis damage Confirm clinical diagnosis Evaluate possible concomitant disease Assess therapeutic response Liver Biopsy 20% sampling error Tendency to under stage fibrosis Pathologist inter-individual variability, experience Not without risk – Pain – Bleed – Perforated viscous Treatment Pegylated interferon SQ weekly with ribavirin PO twice daily for 24 to 48 wks Difficult. Fatigue universal Common adverse effects: – Flu like symptoms fever, myalgia, cephalgia – Nausea, diarrhea, weight loss – 1/3 – Irritability, anxiety, anger, insomnia, impaired concentration 1/3 – Depression – severe in < 1:1,000 – Rash, pruritis, alopecia Treatment—Adverse Effects Neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia – growth factors and/or dose reduction may be required Retinopathy - rare Immune mediated disorders < 1% – Thyroid, diabetes, psoriasis, neuropathy Teratogenic – protection against pregnancy required Monitoring While on Treatment Significant other/caregiver to help pick up changes in mood that require treatment Frequent phlebotomy, office visits Look for side effects and treat Some side effects diminish w/ time Hydration, healthy diet important Medication compliance crucial Sleep hygiene Future of Hepatitis C Treatments Protease inhibitor: – VX-950/Telepravir – SCH-503034/Boceprevir Polymerase inhibitor: R 1626 complicated by ADE i.e., StevensJohnson’s syndrome, neutropenia These agents will be add-on to overcome mutations and subsequent resistance Summary Hepatitis C is epidemic Most don’t know they are infected Treatment is difficult, but most can handle it with appropriate support systems in place and careful monitoring Hepatitis C is the driving force behind the rise in cases of HCC New treatments on the horizon purport to shorten treatment duration References Wise M, Bialek S, Finelli L, Sorvillo F. Changing trends in hepatitis Cmortality in the United States. 19952004. Hepatology; 47,4:1128-1135. Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis C Cryoglobulinemia – Clinical triad of purpura, arthralgias, weakness – May affect kidneys, peripheral nerves, or brain Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis Porphyria cutanea tarda Leukocytoclastic vasculitis Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis C Sicca syndrome/Sjogren’s syndrome Sero negative arthritis Autoimmune thyroiditis Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Hamman-Rich syndrome) Polyarteritis nodosa Lichen planus Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis C Mooren’s corneal ulcer Aplastic anemia Overt B-cell lymphomas Psychological disorders, including depression Osteosclerosis Higher incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease A Growing Epidemic NAFLD A Continuum Simple May steatosis – a benign condition progress to steatohepatitis – > fibrosis - > cirrhosis - > hepatic decompensation - > liver failure - > premature death without liver transplantation Natural History of NAFLD Simple steatosis affects 60% of the obese These individuals will not progress to steatohepatitis and cirrhosis Where is the fat in fatty liver? Obesity An Epidemic Obesity NHANES data 2003-2004 shows: – 32% of U.S. adults aged > 20 are obese – 17% U.S. children and teens are overweight Becoming one of the most important chronic liver diseases in children and adolescents Affects 2.6% to 9.8% of this young population, up to 77% of the obese. 1 Rapid progression to cirrhosis in some children and young adults Obesity Defined “Just right”: Adult w/ body mass index (BMI) 20 to 25 kg/m2 Overweight: BMI 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 Obese: BMI > 30 kg/m2 Morbid obesity greater than 35 Natural History of NAFLD 20 – 25% will develop the progressive form of NAFLD, called “Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis” (NASH) One of the most common liver diseases in the developed world 15% will progress over five years to cirrhosis Cirrhosis increases risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma – Greater w/ increasing BMI – Male > Female Risk Factors for NAFLD Waist : hip ratio > .9 in males, > .85 in females (apple shape), BMI > 30 Medications: amiodarone, tamoxifen, corticosteroids, estrogens, agents used in treatment of AIDS indinavir Severe weight loss, i.e., jejunoileal bypass Metabolic syndrome The Metabolic Syndrome About 47 million U.S. adults affected 1 million 12 to 19 year old adolescents World Health Organization definition of the metabolic syndrome: – BP: > 140/90, hyperglycemia, high waist to hip ratio, triglyceride > 150 and/or low HDL NAFLD, NASH are the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome Epidemiology NAFLD prevalence 3-6 – 17% to 33% of U.S. adults – Bariatric surgical candidates 84% to 96% NASH prevalence: – 5% to 17% – Bariatric surgical candidates 25% to 55% CIRRHOSIS prevalence: – 0.8% to 4.3% – Bariatric surgery patients 2% to 12% Pathophysiology Obesity and fatty liver are often accompanied by a chronic, low grade inflammatory state mediated by the immune system The pro inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha, interferon beta, interleukin-6, C reactive protein, and other acute phase proteins are released by adipocytes and macrophages Evidence suggests that the inflammatory response itself may be responsible for insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease Pathophysiology In the liver, Kupffer cells release cytokines that activate stellate cells to begin forming scar tissue (fibrogenesis) Oxidative stress enhances insulin resistance; however, antioxidants, i.e., vitamin C and vitamin E have not been shown to improve hepatic histology Diagnosis of NAFLD In the U.S. NAFLD is the most common cause of elevated transaminases. ALT usually > AST Persistent elevation of AST and/or ALT @ least 1.5 x ULN for six months Exclusion of other causes of liver disease Ethanol consumption < 140g/wk in men, < 70 g/wk in women Diagnosis of NASH NASH is a tissue diagnosis Liver biopsy required (unless “cryptogenic” cirrhosis already present) Biopsy can accurately diagnose NASH, exclude other causes of liver disease, stage, and determine prognosis Consider when age > 45, need to gain commitment to treatment If cirrhosis, consider referral to hepatologist Histology Features of NAFLD include: Steatosis (0-3) Hepatocyte ballooning (0-3) Lobular inflammation (0-2) Fibrosis (0-4) Grade of necroinflammatory change is scored from 0–8 Stage of fibrosis is scored 0-4 Management No approved pharmacotherapy at this time, though active research is ongoing Control diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia. Therapeutic lifestyle changes are the cornerstone of management Extremely resistant to treatment; dietician consultation critical Discourage rapid weight loss (can worsen liver disease) Case Study Middle-aged female BMI 31.4 95 -----------------------------< .9 104 220 Non-drinker DM-2 on oral agents Viral hepatitis panel negative, normal platelet count and albumin Right Upper Quadrant Ultrasound suggests fatty infiltration of liver Case Study 30 y/o M BMI 34 Alcohol consumption about 24g/day No previous hepatitis B immunization Family history of diabetes, coronary artery disease Takes no regular medications or supplements Case Study (cont.) 54 --------------/------< .8 79 120 Ultrasound normal Stops all alcohol and repeat LFTs show: 49 --------------/------< .7 38 120 References 1. 2. 3. Nobili V, Manco M, Devito R, et al. Lifestyle intervention and antioxidant therapy in children with non alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 2008;48:119128. Fortson J, Howe L, Harmon C, & Sherrill WW. Targeting cardiovascular risk: Early identification of insulin resistance. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 2008;319-325. Diehl AM. Hepatic complications of obesity. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 2005;34:45-62. References 4. Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2006;40(3 suppl 1):S5-S10. 5. Sanyal AJ. Gastroenterological Association technical review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1705-1725. 6. MCullough AJ. Pathophysiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2006;40 (3 suppl 1):S17-S29. References 7. Jonson JR, Barrie HD, O’Rourke P, Clouston AD and Powell EE. Obesity and steatosis influence serum and hepatic inflammatory markers in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2008;48:80-87.