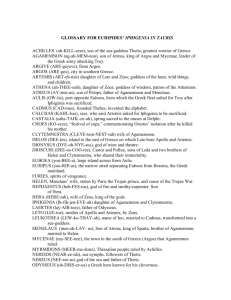

GTBOOKS- Formal Essay 3 Final

advertisement

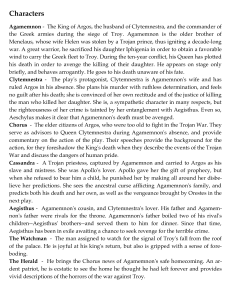

Benjamin Chander GTBOOKS 005 Andy Cavin Considering an opposing view with Aeschylus’ Agamemnon Audiences have been moved and horrified for generations by the tragic fall of the “hero” Agamemnon in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. The chorus portrays the death of Agamemnon and narrates the play in such a way that the audience is led to perceive him as the heroic warrior who is unjustly slain by his murderous wife. Considering this long lasting perspective, it is compelling to ponder, what if Agamemnon is not truly the martyr that the chorus presents him to be? What if Clytemnestra is, in fact, the true sufferer of the story as she is portrayed as a murderous harlot for merely carrying out justice when no one else will? Is Clytemnestra acting unjustly in avenging the death of her daughter and saving the house of Atreus from Thyestes’ curse? Considering such questions is to resist the gradient of the story and consider the possibly justified motives of Clytemnestra. By critically considering the text and how the audience is influenced by the text’s portrayal of Clytemnestra as the enemy of the play, in addition to resisting the gradient of the piece, it can be seen that Clytemnestra has justifiable motives for acting in the manner that she does in addition to murdering Agamemnon and Cassandra. At the end of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, the chorus condemns Clytemnestra for killing Cassandra through repeated verbal assaults on Clytemnestra’s character and motives: “Woman, what evil food nurtured by the earth or what drink sprung from the flowing sea have you tasted, that you have put on yourself this murder?” (1392-1409). The chorus’ repeated judgments lead the audience into feeling contempt for Clytemnestra while at the same time painting her as the antagonist of the play. This being noted, it is essential to consider the motives of Clytemnestra and to recognize that the events of the piece allows for the audience to notice the justified motives of her character. The chorus gives Clytemnestra time to justify her actions and in turn gives the audience the chance to recognize her as a character who is merely acting upon natural human emotion, just as any individual would: “And this woman here, the captive and soothsayer and bedfellow of him, the trusty prophetess who shared his couch, the public harlot of the sailors’ benches…[the] side-dish for his bed…” (1440-1431). Clytemnestra’s actions of murdering Cassandra can be justified by considering her circumstances in the play. After waiting ten long years for her beloved husband to return home from war, Clytemnestra is met with a dirty harlot who has taken her place by her husband’s side. Any other individual in the same position as Clytemnestra would be outraged at witnessing such an event and would take aims at getting rid of Cassandra. In addition to noticing the surface happenings of this part of the piece, by also noticing the nuances of Clytemnestra’s love for Agamemnon, as she professes them earlier in the play, the magnitude of her anger and thus the justification of her actions can be seen. “…[F]or what day’s light dawns sweeter for a woman than this, when a god has brought her man safe home from a campaign and she unbars the door?...” (602-604). By considering the fact that Clytemnestra truly loves Agamemnon and by reflecting on the circumstances that she is placed in, the audience can sympathize with her character and transcend the judgments of the chorus to come to the conclusion that Clytemnestra is not insane character that she is portrayed to be. Many would agree with the fact that Clytemnestra truly loves Agamemnon, as she has protected his estate for ten long years while he was away, in addition to taking the time to profess her love for him before the chorus. At the same time, some may side with the chorus and bring up the detail that Clytemnestra cannot truly love Agamemnon as she gives herself to Aegisthus in Agamemnon’s absence. This is simply not the case and it can again be argued that her actions are justified as a result of the situation she is placed in. Clytemnestra, as a woman, has strong physical needs that must be met and in light of her being without a man to fulfill these needs for ten long years, her actions of finding a man can be justified. Though Clytemnestra may find another man besides Agamemnon to appease her sexual necessities, the fact that he is her one true love can be seen through her jubilance that he is finally returning from war, “I may make best haste to receive my honored husband on his return…” (601-602). Again, by considering Clytemnestra’s dire positions in the play, the audience can come to see that her actions can be justified despite the persuasive nature of the gradient of the piece. The chorus, in addition to condemning Clytemnestra at the end of the piece in regards to the murder of Cassandra, also denounces her for murdering her husband, Agamemnon: “Great is your daring, arrogant your words; just as your mind is maddened by the bloody deed, the bloodfleck in your eyes is clear to see” (1426-1428). The audience’s feelings toward Clytemnestra are directed toward hate and malice as they are influenced by the negative portrayal that the chorus provides. By transcending the words of the chorus and analyzing the justifications that Clytemnestra explicates, it can be seen that Clytemnestra is incorrectly presented as the antagonist in the play. Considering Clytemnestra’s words to the chorus in regards to Agamemnon slaughtering their daughter, Iphigenia, it can be seen that her actions are not without reason. “Now you pass judgment on me…though then you raised no opposition to this man, who holding it of no special account, as though it were the death of a beast, sacrificed his own child, a travail most dear to me, to charm the winds of Thrace?” (1413-1418). By considering Clytemnestra’s reasoning for killing Agamemnon, it can be seen that her actions are justifiable in response to those actions of Agamemnon. Considering the situation Clytemnestra is in; being without her husband and daughter for ten long and lonely years, she finds out that her one and only offspring has been slaughtered like a cow by her own spouse, it should be unquestionable why she partook in the acts that she did. The pain and rage that would be sparked from within the heart of any mother in such a situation would be unbearable and uncontrollable. Similarly, the rage that Clytemnestra experienced must have been uncontrollable. By considering the feelings that a mother, who has but one single child to care for, would experience in such a sequence of events, the audience can come to sympathize with Clytemnestra and recognize the motives she had for her actions. In addition to considering the outrage that Clytemnestra must have experienced and connecting with her as a result, the audience can also sympathize with Clytemnestra as she is merely acting as a force of justice in the play when no one else will. “I swear by the justice accomplished for my child… to whom I sacrificed this man…” (1433-1434). In extinguishing Agamemnon, Clytemnestra is doing exactly what the other characters should have been brave enough to do: take justice into their own hands. In addition to letting justice take its course, Clytemnestra acts as a force of justice as Agamemnon, “pay[s] for the deed his father’s hand contrived” (1582). By indirectly acting as a tool of justice as the curse of Thyestes is fulfilled, (that Atreus and his family will pay for, “serv[ing] to [Thyestes] a feast of his children’s flesh” (1593)), the actions that Clytemnestra partakes in can be sympathized with by the audience. By carefully considering the motives of Clytemnestra, in addition to the overarching ramifications of her actions, the audience can transcend the incriminating words of the chorus to the higher conclusion that Clytemnestra’s actions are justifiable by the situation she is placed in. By critically analyzing the text and the biases that the chorus presents to the audience by incorrectly castigating Clytemnestra for her actions in the play, it can be seen that Clytemnestra has justifiable motives for acting in the manner that she does in regards to murdering Agamemnon and Cassandra. By transcending the surface happenings and narrations of the play, it can be seen that there is more to the piece than the well accepted interpretation that has come to be associated with Aeschulus’ Agamemnon. By carefully considering why the gradient of the piece flows in such a way and how the audience is expected to think as the chorus does, one can rise above the obvious details of the play and reach a higher understanding of the piece. Though this play has obvious opportunities to “resist” the chorus and leaves considerable room for a separate interpretation that than of the masses, it is important to note that such interpretations are just that, interpretations. No single view of a particular piece of literature has considerable more merit than that of another as the interpretation of any single piece can be derived from the many controversial events throughout the plot of that piece.