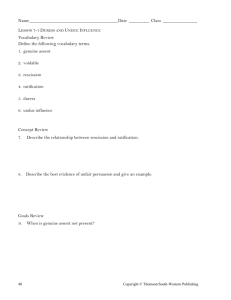

Free Consent1

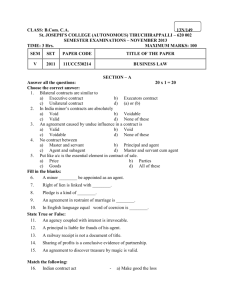

advertisement