How the First Americans Became Indians

advertisement

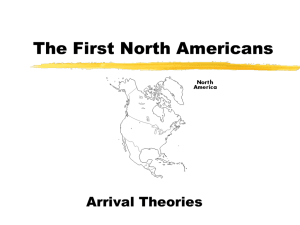

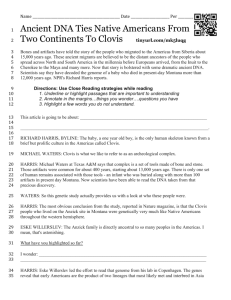

The First Americans Name: Period: Table of Contents Unit Learning Targets…………………………………………………………………….. 2 World Map ……………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Time For Kids – “Early Man in America” ………………………………………….. 4 Volume 11, Number 21, March 17, 2006 “Finding the First Americans”…………………………………………………………. 6 The New York Times / May 12, 2012 “Found: Fine American Fishing Tackle, 12 Millennia Old”………………… 8 www.newscientist.com / March 3, 2011 “How the First Americans Became Indians”……………………………………... 10 A History of US: The First Americans textbook “Native Americans of the Southwest”……………………………………………… 13 History Alive! textbook “A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030”………………………………………………………….. 14 I Wish I’d Been There: Twenty Historians Bring to Life the Dramatic Events That Changed America 1 Unit Learning Targets N OVICE A PPRENTICE P RACTITIONER M ASTER I CAN CRITIQUE THE C LOVIS FIRST T HEORY USING EVIDENCE FROM SECONDARY SOURCES . o o o o o Identify the Bering Straight on a map Draw the migration path the First Americans took from Asia to America Demonstrate how the Beringia Land Bridge was formed Define artifact Identify the difference between a Primary Source and a Secondary Source N OVICE A PPRENTICE P RACTITIONER M ASTER I CAN MAKE COMPARISONS BETWEEN THE CULTURE OF A SOCIETY AND ITS GEOGRAPHY . o o Define culture Define region 2 World Map 3 “Early Man in America” 4 “Early Man in America” 5 Finding the First Americans By ANDREW CURRY The NY Times published May 18, 2012 Uphill http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/20/opinion/sunday/who-arrived-in-the-americas-first.html?_r=0 WHEN and how did the first people arrive in the Americas? For many decades, archaeologists have agreed on an explanation known as the Clovis model. The theory holds that about 13,500 years ago, bands of big-game hunters in Asia followed their prey across an exposed ribbon of land linking Siberia and Alaska and found themselves on a vast, unexplored continent. The route back was later blocked by rising sea levels that swamped the land bridge. Those pioneers were the first Americans. The theory is based largely on the discovery in 1929 of distinctive stone tools, including sophisticated spear points, near Clovis, N.M. The same kinds of spear points were later identified at sites across North America. After radiocarbon dating was developed in 1949, scholars found that the age of these “Clovis sites” coincided with the appearance at the end of the last ice age of an icefree corridor of tundra leading down from what is now Alberta and British Columbia to the American Midwest. Over the years, hints surfaced that people might have been in the Americas earlier than the Clovis sites suggest, but the evidence was never solid enough to dislodge the consensus view. In the past five years, however, a number of discoveries have posed major challenges to the Clovis model. Taken together, they are turning our understanding of American prehistory on its head. The first evidence to raise significant questions about the Clovis model emerged in the late 1970s, when the anthropologist Tom Dillehay came across a prehistoric campsite in southern Chile called Monte Verde. Radiocarbon dating of the site suggested that the first campfires were lighted there, all the way at the southern tip of South America, well before the first Clovis tools were made. Still, Professor Dillehay’s evidence wasn’t enough to persuade scholars to abandon the Clovis model. But in 2008, that began to change. That year, researchers from the University of Oregon and the University of Copenhagen recovered human DNA from coprolites — preserved human feces — found in a dry cave in eastern Oregon. The coprolites had been deposited 14,000 years ago, suggesting that Professor Dillehay and others may have been right to place humans in the Americas before the Clovis people. 6 This discovery inspired other scholars to re-examine old finds with new techniques. In the 1970s, for instance, a farmer in Washington State found a mastodon rib with a bone shard lodged in it, as if the mastodon had been killed with a weapon. Since the mastodon remains predated the earliest Clovis sites by eight centuries, the nature of the finding was initially disputed. But in 2011, researchers led by the Texas A&M archaeologist Michael R. Waters announced that by analyzing the rib and the embedded fragment using scanning and modeling techniques, they had confirmed that the embedded bone was a spear point — strongly suggesting that humans in the Americas were hunting the animals with bonetipped spears long before the end of the ice age. The Clovis model suffered yet another blow last year when Professor Waters announced finding dozens of stone tools along a Texas creekbed. After using a technique that measures the last time the dirt around the stones was exposed to light, Professor Waters concluded, in a paper in Science, that the site was at least 15,000 years old — which would make it the earliest reliably dated site in the Americas. The archaeological evidence challenging the Clovis model is also receiving support from genetic studies. Having compared the DNA of modern American Indians with that of groups living in Asia today, scholars have estimated that the last common ancestor of the two peoples probably lived between 16,000 and 20,000 years ago. That figure doesn’t square with the arrival of the Clovis people from Asia only 13,500 years ago. Where does this leave us? We now know people were in the Americas earlier than 14,000 years ago. But how much earlier, and how did they get to a continent sealed off by thick sheets of ice? Working theories vary. Some scholars hypothesize that people migrated from Asia down the west coast of North America in boats. Others suggest variations on the overland route. One theory even argues that some early Americans might have come by boat from Europe via the North Atlantic, despite the fact that the DNA of modern American Indians does not suggest European origins. After 80 years under Clovis’s spell, scholars are once again venturing into unknown territory — and no one is ready to rule anything out yet. 7 Found: Fine American Fishing Tackle, 12 Millennia Old March 03, 2011 by Ferris Jabr http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn20195-found-fine-american-fishingtackle-12-millennia-old.html?full=true&print=true Mountainous A treasure trove of finely crafted fishing spearheads from 12,000 years ago has been discovered on the Channel Islands of California. They are a clue to the lifestyles of some of the earliest American settlers, and suggest that two separate cultures lived in North America at the time: one, the well-known Clovis culture, lived inland and feasted on mammoths, mastodons and other mammals; the other was a coastal culture with a taste for seafood. The archaeologists who made the find believe that the two groups were distinct, but shared trade links. Jon Erlandson of the University of Oregon in Eugene and his team poked around caves, springs and likely sites of ancient human settlement on the islands of Santa Rosa and San Miguel, and found more than 50 shell middens – large trash heaps of discarded seashells, chipped stone tools and animal bones – which they dated to between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. They think that during this period early Americans used the islands for seasonal hunting camps, most likely in the winter when fresh water would have been plentiful. The remains suggest that early colonisers hunted birds such as overwintering Canada geese, snow geese, albatross and cormorants – and possibly marine mammals like otters and seals – but also harvested a variety of shellfish from kelp forests, including mussels, red abalone and crabs. Such a diet contrasts with the big-game hunters who lived on the mainland at the time and liked to chase camels, horses and mastodons. 8 Delicate work But what astonished Erlandson and his colleagues were the tools they found near the middens. Team member Todd Braje of Humboldt State University in Arcata, California, describes finely crafted barbed spearheads. "We found very thin, expertly made projectile points and it blew us away that these delicate flint-knapped points are this old," he says. Such tools are generally only found at more recent sites. These fine, barbed points are markedly different from those previously found at Clovis sites, which tend to be simple, fluted points. This hints at the coexistence of two separate groups of people in North America at the time. However, Loren Davis of Oregon State University in Corvallis points out that the team also found Clovis-like spearheads on the islands: he says that tools he has dug up on the North American mainland look nearly identical to some of the ones Erlandson and his team found. "That means peoples on the Channel Islands and people in western Idaho, for example, were at one point exposed to the same ideas about how to make technology," Davis says. A likely explanation is that the two groups shared some kind of trade. By land or sea? That Erlandson and his teams found the remains on what was once a single island off the coast of modern-day California is also significant. There are many hypotheses for how humans colonised North America: one popular scenario is that they crossed over from Asia across a land bridge that once linked Siberia and Alaska. But some historians believe at least some of the early settlers were seafarers, and either dropped down along the coast from Alaska or even crossed over from Japan. Erlandson and his colleagues say their new finds support the idea that the first people to inhabit the Americas were mariners, or perhaps that land and sea-based migrations occurred in tandem. It's too early to say for sure. Davis points out – and Braje concedes – that the Channel Island sites are not the oldest in the Americas, so they do not tell us about the very first pioneers. Still, Braje says, "this pushes back the chronology of New World seafaring to 12,000, maybe 13,000 years ago. It gets us a big step closer to showing that a coastal migration route happened, or was at least possible." 9 How the First Americans Became Indians 10 How the First Americans Became Indians 11 How the First Americans Became Indians 12 Native American Cultural Regions 13 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 14 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 15 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 16 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 17 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 18 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 19 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 20 A Day in Cahokia - AD 1030 21