Writing

advertisement

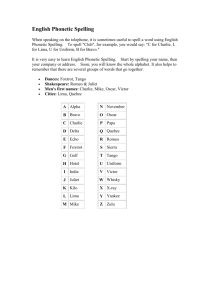

Writing Systems • Pictographs (symbol looks like the thing being represented; no major role in current writing systems) • Ideographs (symbols represent words or concepts) • Syllabic writing (symbols represent syllables) • Alphabetic writing (symbols represent individual speech sounds) • Morphophonemic writing (variation on alphabetic writing – English spelling is mostly morphophonemic) Important Note Before We Go Through Each Writing System There are no writing systems in use that are purely of any one type. For example: 1. Chinese characters are mainly ideographs, but with some characters specifying sound rather than a whole word. 2. Alphabetic characters in the writing system used for English mainly specify sound, but ideographs are also used (&, %, $, 4, =, ? …). Pictographs What does this sign mean? The tree component only is a pictograph – meaning conveyed directly because it looks like the thing it represents. Note: All four kinds or writing are used on this sign: (1) tree=pictograph, (2) “SALE”=alphabetic, (3) “4”=syllabic, (4) Exclamation point=ideograph. (More about this later.) But the tree is a pictograph. What does this pictograph mean? Mountains? Some particular mountains (Rockies, Adirondacks)? Scenic view ahead? Landscape mode (rather than portrait mode)? Who knows? What picture do you draw for abstract concepts like sadden, hypothetical, creative, ambitious, or even verbs like stall (as in “My car stalled.”) or fidget? What does this pictograph mean? What do these pictures mean? How did you know? These are ideographs – meaning is assigned by convention; i.e., we learn to interpret them in a particular way. In this case, the state compels us to learn them. Also called ideograms and logograms. Other Ideographs !@#$%&1234…? Ideographs may or may not be iconic (iconic = looks like the thing being represented). The road signs were all iconic. The symbols above are not. Iconic or not, meaning is assigned by convention – we all agree that ‘%’ means “percent”, and that the squiggly arrow means “curvy road ahead.” Ideographs provide no clues about pronunciation; i.e., there is nothing in the numeral “2” that tells you to pronounce the symbol [tu]. Ideographs Used in Chinese Writing • Any iconic elements are probably lost on most readers • Symbols represent whole words or concepts • No clues to pronunciation (usually) • Both concrete (sun, river, …) & abstract words (strength, good, peaceful) are represented Chinese writing is not purely ideographic. Some characters represent broad semantic categories (e.g., person, insect, metal) and others provide pronunciation clues. Chinese writing is not purely ideographic. Some characters represent broad semantic categories (e.g., person, insect, metal) and others provide pronunciation clues. Writing systems derived from Chinese are in use for Japanese (kanji), Korean (hanja). Downsides to ideographic writing. 1. Representation is (mostly) at the word level; character set is really huge. The number of symbols is in the many thousands (compare this number to the 26 Roman letters). 2. Clues are not provided to pronunciation (though Chinese is not purely ideographic). Encounter a new symbol? You’re stuck. Not true of alphabetic writing. What happened the 1st time you encountered the word “bombastic”? 3. Place names, proper names, foreign words, etc., can be a headache. Downsides to ideographic writing (cont’d) 4. Specifying ideographs on a computer keyboard requires some creativity (a one-toone key-to-symbol relationship would require an immense keyboard. The upside: The writing system is language independent. Language independence means that anyone who knows what the ideographs mean can understand what is written – no matter what language they speak. This is a really big deal in China. “Standard” Chinese: Mandarin, but a large number of “dialects” which are more properly viewed as separate languages. Some of the mutually unintelligible “dialects”: Shanghainese, Cantonese, Southern Min, Hunanese, Northern Min, Eastern Min, Central Min, Dungan, … several others. Why is language independence important? A newspaper article or book can be read equally well by speakers of all of these languages. This would not be true with an alphabetic writing system, or any other system that conveyed sound rather than meaning. This explains why China – with many mutually unintelligible languages – will probably never move to alphabetic writing. Syllabic Writing Main idea is pretty obvious: Each symbol represents a syllable. Japanese syllabary (Syllabary=set of symbols to represent the syllables of a language) Hiragana: One of two Japanese syllabaries. Hiragana base characters a ∅ あ k か s さ t た n な h は m ま y や r ら w わ i い き し ち に ひ み り ゐ u う く す つ ぬ ふ む ゆ る e え け せ て ね へ め れ ゑ o お こ そ と の ほ も よ ろ を ん (N) Note: The 1st row (identified with the “∅” symbol) lists symbols used to specify syllables consisting of a vowel by itself; e.g., the 1st syllable in the English word “Okay”. Key difference between syllable-based writing and logographs/ideographs: Syllabic symbols represent sound, not whole words. Symbol set for a syllable-based writing system is called a syllabary. Syllabaries are in use for several languages, including Japanese (two, in fact: katakana and hiragana), Korean (hangul), Inuit, & Cherokee. Syllabaries are a good choice for languages with a fairly small number of unique syllable types. Japanese has a small number of unique syllable types because: (1) it has a small phonemic inventory, and (2) it has many constraints on permissible syllable types (I’ll tell you what this means soon). Japanese: Somewhere around 50 unique syllable types. (Why? Japanese has just 5 vowels, a little over a dozen consonants, no consonant clusters; syllable types consist mainly of V and CV.) English: Many thousands of syllable types (~3 times as many vowels as Japanese, ~twice the number of consonants, lots & lots & lots of consonant clusters. For example, a separate syllabic symbol would be needed just to represent the word sphinx. That symbol would have no other use. Same thing with the word strength. Would syllabic writing be a good choice for English? Not impossible, but it would be cumbersome. Alphabetic Writing Sound is represented rather than whole words, but sound is represented at the phoneme level, not the syllable level. “Ideal” alphabetic system: 1 letter = 1 sound. No system in use meets this ideal, but some are fairly close. English isn’t one of the close ones. (Big surprise, eh?) Roman Alphabet English (along with many other languages) is written using the Roman alphabet. Lineage (i.e., where the alphabet come from): (1) Hieroglyphics -> West Semitic Syllabary (Phoenicians – hence the word phonetics) Hieroglyphics was a mix of ideographs & syllabic symbols; Phoenicians ditched the ideographs and kept a 22-symbol syllabary. (2) West Semitic Syllabary -> Greek Alphabet Greeks added some vowel symbols and turned the syllabary into an alphabet. Origin of Roman Alphabet (cont’d) (3) Greek Alphabet->Roman Alphabet Romans added a few symbols and redefined others to suit the phonetic inventory of Latin. Quick Summary 1. Hieroglyphics (mix of ideographs & syllabic symbols) 2. W. Semitic Syllabary (keeping syllabic symbols only) 3. Greek alphabet (switch from representing sound at the syllabic level to the phoneme level) 4. Roman alphabet (a few changes to better fit the phonetic inventory of Latin) From Simpson Bible Stories Pharaoh (Principal Skinner) dictating a letter in hieroglyphics: “… giant eye, dead fish, cat head, cat head, feather, picture of a guy doing this …”. English Spelling Stinks Big Time English is not the only spelling system that is problematic due to inconsistent letter-tosound relationships. Many spelling systems suffer from this problem. But English gets the prize as the worst, at least here on earth. Check out this link: http://redux.com/stream/item/1831091/Dumb-English-Spelling Why English Orthography Stinks 1. Roman alphabet is poorly suited to English for a very simple reason: The sound inventories of the two languages are very different, especially the vowel inventories. Latin: 5 monophthongs, no diphthongs English: ~12 monophthongs, 3 diphthongs = 15 How do you represent 15 vowels with 5 symbols? *** NOTE: The poor fit of the Roman alphabet to the phonetic inventory of English is the 1st item on this list, but it is far from the most important problem. (More to come.) *** Problem with the Roman alphabet could be dealt with by consistently using combinations of letters to represent sounds. A lot of this is done: met–meat, bit-beat, cot–coat, ... But: it isn’t done w/ much consistency. Letter-tosound associations are all over the place. /i/: ski, flee, meat, people, physiology, fetus, ... Same problem with consonants: /f/: foam, phone, rough, etc. Many other examples. G.B. Shaw: “fish” = ghoti (gh as in cough, o as in women, ti as in nation) 2. There are sounds in some words that could easily be represented with the Roman alphabet but, for one reason or other, they are not. beauty: What speech sound follows the [b]? user: What speech sound begins this word? union: What speech sound appears twice in this word but is not represented at all in the spelling? The “stealth” sound is [j] in each of these words ([bjuɾi], [juzɚ], [junjən]), but English spelling provides many other examples of sounds that could be represented with the Roman alphabet, but are not. Moral: The big problem isn’t really the Roman alphabet. The alphabet wasn’t designed for English, but the liabilities could be dealt with. They aren’t. How’s come? The Real Culprits 1. Spelling standardization is surprisingly recent, and it was never done in a systematic way. As recently as the 19th C even educated writers spelled (NOT spelt) however they felt like. When spelling was finally standardized, it was done in a haphazard way. So, spelling was standardized but not systematized. Systemizing spelling is what was really needed, but this wasn’t done. Quick note: On exams I sometimes ask students to list and explain the most important problems with English spelling. Q: What is wrong with the answer “spelling standardization” (which I get quite often)? A: It does not answer the question. Suppose I had told you that a major problem with English spelling was spelling standardization, then moved on to the next one. Would this have meant anything to you? Lesson: You do not need to write a book, but you should aim to capture the key idea. The Real Culprits (cont’d) 2. Historical sound change: Pronunciation changes over time; spelling usually stays put. knight, knife – the ‘k’ ([k]) used to be pronounced gnaw, gnat – same deal with the ‘g’ ([g]) cough, rough – words used to end with a speech sound that is no longer in the phonetic inventory of English – the consonant that is at the end of the name “Bach”, as it is spoken by eggheads. 3. ”Foreign born” words. Most English words started out life as part of the vocabulary of some other language. The habit is usually to retain the original spelling. pizza, colonel, cello, junta, chassis, psalm, repertoire, liaison, sauna, coup, algorithm, decipher, coffee … Result: Mishmash of different and wildly inconsistent spelling conventions. This is almost certainly the most important of the “culprits”. 4. Others – See MacKay (Chapter 3), but the three points discussed above are the main ones. These are the ones I’d like you to know (& be able to explain). For the Etymologically Curious pizza: colonel: Italian French (who borrowed it from the Italian colonnello, meaning ‘little column’) cello: junta: chassis: psalm: repertoire: liaison: sauna: coup: algorithm: decipher: coffee: Italian Spanish French Greek French French Finnish French Arabic Arabic Arabic OK, so English spelling has problems everywhere you look. These problems explain why: It took most of us forever to learn to spell. Most of us still have problems from time to time; more than occasionally for some of us. It’s unusual to find people who consider themselves to be good spellers. It’s about as common as finding someone who says, “Yes, I find that algebra comes very easily to me.” BUT: Is English spelling really as bad as all that? Not really. IMPORTANT NOTE The last topic we’re going to discuss addresses exactly this question: English spelling is a mess, no doubt about. But is it really quite as messed up as it seems? The answer is NO. The fact that English spelling is not phonetic is NOT a design flaw. English spelling is intentionally not based on a phonetic design principle; i.e., it is purposely not trying to represent surface phonetic details. Instead, it is based on something called a morphophonemic principle. This is the most important concept in the entire section on writing. IMPORTANT NOTE (cont’d) A quick preview of where we’re heading with this. In spite of all of its many and very real flaws, there is an elegance to our spelling system (and all other alphabetic spelling systems). It’s called the morphophonemic principle. Details very soon, but here’s the basic idea: The spelling system is purposely designed NOT to represent surface phonetic details. Instead, it’s designed to represent more abstract: (1) morphological regularities, and (2) phonemic (not phonetic) regularities. IMPORTANT NOTE (last thing) The morphophonemic principle is not a hard idea, and pretty much everybody gets it. So, here goes ... Two starting points: 1. English spelling could not be made strictly phonetic even if we wanted it to be. 2. We would not want it to be strictly phonetic. 1. It Could not make phonetic even if we wanted it to. a. No solution to dialect variation. Whose dialect should we use? British? Australian? Irish? Scottish? S. African? American? Suppose we chose American. Which dialect? Brooklyn? South Philly? Rural Alabama? Looosiana? We wouldn’t want spelling to vary across these communities – i.e., you’d want a Brit to be able to read a book written by an Aussie. This problem is not solvable. b. No easy solution to changes in pronunciation patterns over time. Speech patterns change over time – and much more quickly than most people imagine. How often do you want to reprint your books? So, it would be somewhere between difficult and impossible to make English spelling phonetic. ______________________ Q: Would we want spelling to be phonetic? A: No. No doubt about it. Why? Because morphophonemic spelling is a much better idea than strictly phonetic spelling. Major Point #1: English spelling represents underlying morphological regularities, not superficial phonetic facts. Simpler than that sentence makes it sound. approximate, approximately Note the highlighted letter “a” (NOT /a/ or [a]). Is it pronounced the same way in the two words? [No] Would you want the spelling to: (1) change to reflect the difference in pronunciation? or (2) stay the same to reflect the fact that these are two versions of the same word, related to one another by a morphological rule? I vote for #2. This is not a minor phenomenon in English spelling. It’s all over the place. nation – nationality medicine - medicinal magic – magician social – society discuss – discussion televise – television (different sounds [e,æ], same letter) (different sounds [ɛ,ə], same letter) (different sounds [k,ʃ], same letter) (different sounds [ʃ,s], same letter) (different sounds [s,ʃ], same letter) (different sounds [z,ʒ], same letter) In all cases the spelling reflects not phonetic details but the deeper and more important fact that the word on the right is derived from the one on the left by morphological rules. This is the ‘morpho’ part of morphophonemic. English spelling is morphophonemic, not phonetic. This is a good thing, not a bad thing. Major Point # 2: English spelling represents underlying phonemic regularities, not surface phonetic facts. walk – walks cat – cats dog – dogs pan – pans Phonological rule: If the word ends in a voiceless consonant, add [s]; otherwise, add [z]. But note that the spelling does not reflect this – always get ”s” in spelling. On an abstract, phonological level, it’s an /s/ in both cases: a sound-pattern rule handles the phonetic detail of whether this “abstract” /s/ is realized as [s] or [z]. Similar to the morphology thing: The spelling system reflects underlying linguistic (phonemic/phonological) facts, not superficial phonetic facts. This is good. Point #2 (cont’d): English spelling represents underlying phonemic regularities, not surface phonetic facts. walk – walks cat – cats dog – dogs pan – pans The example in the previous slide (shown above) illustrates the phonemic part of the morphophonemic principle. Point #2 (cont’d): This is very smart. Why? There is no need to use the spelling “dogz,” even though it is phonetically more accurate. The ‘z’ is not needed because the reader already knows that the word is pronounced [d ɔgz]. How? Even VERY young kids have already learned this rule. So, the information that the spelling system fails to provide to the reader (whether the plural marker is pronounced [s] or [z]) is something that they already know. The unvarying “s” in spelling quickly tells the reader “this word is plural,” which is all they need to know. Example 2: backs – bags ([bæks] - [bægz]) Spelling rules could do one of two very different things: (1) Use an “s” for “backs” and a “z” for “bags” to reflect the difference in phonetic details (phonetic spelling), or (2) Use the same letter in both cases so that the reader can easily see that all that is happening is that the base morpheme (back or bag) is being made plural (morphophonemic spelling). Which kind of system is actually in use in English? Example 3: jogged - walked Note that the spelling shows a “d” in both cases; however, in “walked” the final consonant is actually a [t], while in “jogged” it is a [d]. To work out on your own: 1.In what way is example 3 (previous slide – jogged vs. walked) analogous to example 2? 2.In what way is this another example of morphophonemic rather than phonetic writing? SUMMARY Types Writing Systems (Note: No system is purely any of the types listed) Symbols Represent Words or Concepts Pictographs Ideographs/ Logographs Meaning is (meaning by convention) Supposed to be Obvious examples: Chinese, Japanese (kanji), Dead Some symbols used in End English (! @ # $ % 1 2 3 …) Symbols Represent Sound Syllabaries Symbols=Syllables examples: Japanese (kana) Korean, Inuit, Cherokee Alphabets Symbols=Phonemes examples: English, many others SUMMARY (cont’d) Which kind of alphabetic system is actually in use in English? Phonetic or morphophonemic? The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) In one important sense the IPA does not belong in this section – it is not used as the writing system for any language. No books written in IPA, no newspapers, people don’t write letters to one another in IPA. IPA was developed explicitly for the study and description of the sound patterns of the world’s languages. The IPA has two important features: 1. This alphabet really is phonetic (and sometimes phonemic) – one-to-one correspondence between speech sounds and symbols: The symbol /i/ always specifies the vowel in “beet”; every time the vowel in “beet” occurs the symbol /i/ is used to represent it. 2. Designed to represent the sounds of all of the world’s languages. Does the IPA represent sound at the phonetic level or the phonemic level? Example: How would we transcribe the words “cat” and “scat” or “pot” and “spot” or “bat” and “ban”? Answer: The IPA allows you to transcribe either at the phonetic level (e.g., representing phonetic details such as aspiration or vowel nasalization) or at the phonemic level (i.e., ignoring phonetic details and specifying only the phonemic category). Phonetic: [khæt]-[skæt], [phɑt]-[spɑt], [bæt]-[mæ̃n] Phonemic: /kæt/ - /skæt/, /pɑt/-/spɑt/, /bæt/-/mæn/ Phonetic: [khæt]-[skæt], [phɑt]-[spɑt], [bæt]-[mæ̃n] Phonemic: /kæt/ - /skæt/, /pɑt/-/spɑt/, /bæt/-/mæn/ How are these different? • Phonetic transcription represents fine phonetic details; e.g., the allophonic differences between [kh] and [k], [ph] and [p], [æ] and [æ̃]. How many details? It’s up to you. • Phonemic transcription ignores the fine phonetic details, representing only the broad phonemic categories /k/, /p/, and /æ/. • Phonemic symbols are enclosed in slashes (e.g., /k/, /p/, /æ/) • Phonetic symbols are enclosed in square brackets (e.g., [kh], [k], [ph], [p], [æ], [æ̃]). Which system are we using in this course? Phonetic? Phonemic? We’re using a middle-of-the-road system called broad phonetic transcription. All this means is that we’ll mark some allophonic details but not others. Which ones? Unless I specifically tell you otherwise, do it the way we’ve been doing it in class and in lab. This is not new. You now have a name for it. Q: In this course, which allophonic details do you need to mark? A: The ones we’ve been using in class. There’s nothing that needs to be memorized. Examples: [ɾ] (flap, an allophone of /t/) [ʔ] (glottal stop, another allophone of /t/) [ə] (schwa, an allophone of all English vowels, controlled by stress – if unstressed, you get schwa; more later) For later: syllabic consonants; e.g., the /n/ in: button [bʌʔn̩] cotton [kɑʔn̩] (Note: The diacritic beneath the ‘n’ is supposed to be a vertical line centered beneath the symbol. It does not print correctly. No idea why.) If an allophonic feature such as aspiration (e.g., [thɑp]) or nasalization (e.g., [mæ̃t]) needs to be marked, I’ll let you know.