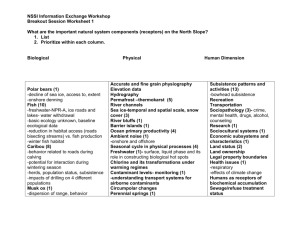

NSSI

advertisement

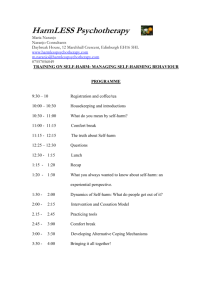

Coping by Injuring: Understanding Non-Suicidal SelfInjury (NSSI) A training provided for the School Nurses Association Tiffany B. Brown, Ph.D., LMFT University of Oregon tiffanyb@uoregon.edu • • • • • • • NSSI definitions, prevalence, features NSSI and the microsystem (family, peers, contagion) NSSI and suicidality Treatment approaches Prevention efforts Support recommendations Potential school protocol What is NSSI? We often misunderstand self-harm. Includes cutting, scratching, burning, picking scabs or interfering with wound healing, punching self or objects, infecting oneself, and bruising or breaking bones. Sudden and recurrent intrusive impulses to hurt oneself. A sense of being “trapped.” An increasing sense of agitation, anxiety, and anger. A constricted ability to “problem solve” or to think of reasonable alternatives for action. A sense of relief after the act of self-harm. A depressive or agitated-depressive mood, although suicidal ideation is not typically present. (Pattison & Kahan, 1983) Prevalence Prevalence • Studies among community samples indicate that approximately 13%–45% of adolescents report having engaged in self-harm at some point in their lifetime (Nock, 2010). • On average, across studies, there is a prevalence rate of 15-20% for adolescents in community samples (Heath et al., 2009). • To put into perspective…NSSI exceeds the rates of other important clinical problems. • Anorexia/Bulimia <2% • OCD <3% Prevalence • Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2008)---data indicated 17% of HS students and 16% of MS students reported having self-injured during the past year. • In a recent adolescent community study the prevalence rate of NSSI using the proposed criteria for DSM-5 was 6.7% (Zettergvist et al., 2013). • Research indicates that these rates are even higher in clinical populations with 40-60% of adolescents. Prevalence • Average age of onset is 12-14 years old (Nock, 2010). • In clinical samples females report more NSSI than males, whereas in community samples there is usually no gender difference (Heath et al., 2009). • Research is finding higher rates among Caucasian and LGBTQ identities (Nixon & Heath, 2008). • To date, there lacks a comprehensive epidemiology study about NSSI. Prevalence • A recent study from Cornell and Princeton Universities, using a sample of almost 3000 students, found that 17% indicated having self-injured (Whitlock et al., 2006). • In a follow-up study involving 8 colleges and more than 11,000 students, Whitlock (2008) found that 15.3% reported some NSSI lifetime; 29.4% reported more than 10 episodes. Self-Harm Features The Role of NSSI • The most expressed notion about the role of NSSI is that it helps the individual escape, manage, or regulate emotions. • Self-punishment • Anti-dissociation • Resisting suicidal urges (stay alive; prevent suicide) Nearly 50% of self-harming individuals report physical and/or sexual abuse during childhood. As high as 90% report they were discouraged from expressing emotions, particularly anger and sadness. Typically, self-harming individuals have a low selfesteem and a lack of healthy coping mechanisms. Self-harm plays a role in reducing emotional pain and serves as a coping mechanism. The brain begins to connect the temporary relief from bad feelings to the act of selfharm. It craves this relief the next time the tension builds. The behavior reduces physiological and psychological tension rapidly. The negative feedback received in regard to their injuries would often trigger more selfharm due to the increased guilt and shame (Yip, Ngan, & Lam, 2003). The most common motives chosen from a list of possibilities were to get relief from distress and to escape their situation (Rodham et al., 2004). “ We just didn’t see any other emotions that we were supposed to display. Knew they were out there, I just didn’t know how to express them. ” “ I would say that [the abuse] affected me, in the sense of not being able to handle things, not being able to cope. I didn‘t learn that. I didn’t learn to cry safely. I didn’t learn how to share my emotions safely. I didn’t learn how to ask for help, in fact, I learned how to not ask for help. ” Trina Microsystem Family Dynamics • People who self-harm describe similar themes within parent-child interactions that impact the development of self-harm as a coping mechanism • Dysfunctional and invalidating family environment (e.g., child abuse and neglect, ignoring or rejecting a child’s emotional expression, reinforcement of extreme emotions of negative affect) • Attachment relationships (e.g. events or injuries to parental bonding and attachment can disrupt the development of emotional regulation capabilities, poor relationship quality ) Family Dynamics • NSSI can arise as a learned response to insecure attachments and attachment injuries. – The student develops a strategy that allows him or her to self-regulate and maintain a functional relationship with the caregiver despite his or her limitations. – This maladaptive attachment experience is internalized by the child and creates a narrative that informs and impacts future relationships, where there is often difficulty forming satisfying and secure attachments with others therefore, adolescents whose parents may be unavailable need to focus on creating a secure attachment with another adult (i.e., foster parent, grandparent). • Parents would benefit from support as they struggle with their own intense emotions around NSSI. • Parents also need direction to SLOW DOWN and NOT OVER REACT. Peer Dynamics • Contagion effect • Peer influence processes (e.g., role of peer conformity, peer socialization effects, peer selection effects, shared stressors) • Possible peer treatment approaches: Psychoeducational group therapy, The Signs of SelfInjury Program (SOSI program) Differentiating Suicidality Self-harm behavior is NOT suicidal behavior Those who self-harm want to live but they feel the only way to remain in control, sane, intact, etc, is to self-harm. This does not mean that suicidal ideation does not exist, but shouldn‘t be assumed just because of the self-harm behavior. 1% Less than of those who selfharm endorse wanting to die as a precipitating reason. (Rodham, Hawton, & Evans, 2004) NSSI and Suicide • NSSI is a risk factor for subsequent suicidal behaviors. • NSSI can be mistaken for suicide attempts - and vice versa. • Some individuals report both NSSI and suicide attempts. NSSI and Suicide • NSSI is associated with higher risk for a suicide attempt when the following are present: – Higher levels of suicidal ideation – Severity of depression – Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder – Impulsivity – Greater levels of negative affect – Apathy & hopelessness – Self-derogation/lack of self-acceptance Brausch & Gutierrez (2009); Muehlenkamp(2010) NSSI and Suicide • Risk Factors – Severity and duration of NSSI (increased suffering) – NSSI becoming less effective in reducing emotional distress – Worsening mental health symptoms • Protective Factors – Hope – Family connectedness, support – Peer social support Brausch & Gutierrez (2009); Muehlenkamp(2010) “ I don’t really correlate the two…there’s several ways to [self-harm], you know. Some people will pull out their hair. I’ve never heard of someone killing themselves by pulling out their hair. ” “ They’re different because suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem and selfharm is my way to deal with those temporary problems. ” “ I was never suicidal, ever, and that is not what needs to be treated. What needs to be treated is our inability to deal with things. ” Treatment Approaches Dominant Approaches • Cognitive behavioral therapies (standard cognitivebehavioral therapy, manual-assisted cognitivebehavioral therapy, problem-solving therapy, and dialectical behavior therapy) • Group therapy (developmental group psychotherapy, Acceptance-based emotion regulation group therapy) No evidence-based pharmacological treatments for selfharm Limitations of Current Approaches • There are no evidence-based treatments for NSSI. • The current research on NSSI presents inconclusive results on the most effective treatment approach. • Themes underlying the treatment modalities that have demonstrated results include addressing maladaptive emotion regulation, intervention programs that serve as an adjunct to treatment as usual (e.g., group therapy), treatment approaches designed to reduce NSSI for individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, and the integration of group therapy. • Lack of studies that address NSSI directly. • Little research focus on treatment of NSSI specifically for children and adolescents. • There are no empirical research studies investigating relational or family treatment approaches. Treatment Recommendations • Utilize treatment approaches that emphasize emotional awareness, emotional acceptance, and emotional regulation, as well as use of healthy coping skills. – Good options are DBT (Linehan, 1993), Mindfulness BasedCBT (Crane, 2008) and ACT (Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007). • Actively involve family members in treatment and consider approaches that emphasize attachment. • Utilize mindfulness and stress-reduction techniques. • Teach social skills and interpersonal effectiveness. – Have the student keep a log or journal about their experiences with self-injury and what thoughts, emotions, and situations are happening when they self-injure, as this information can help them realize when they need to practice newly obtained coping skills. Prevention Prevention Efforts • Despite the apparent need for prevention programs, there are no known evidenced based programs currently in use. • Fortune et al. (2008) found that adolescents believed the best way to prevent self-harm are: – Acess to non-judgmental adults at school – Provide education to teachers, peers, and parents about how to appropriately respond – Reduce concerns about confidentiality and stigma with seeking help Signs of Self-Injury (SOSI) • 2 modules (faculty/staff and students), including a DVD for students • Encourages students to use ACT (Acknowledging the signs, Care for the person and a desire to offer help, and Tell a trusted adult. • SOSI Goals: – Increase knowledge of NSSI – Improve attitudes and perceived capability to respond and refer students or peers – Increase help seeking behaviors – Decrease NSSI acts SOSI Outcomes • Improved attitudes in students towards acceptance & helping those with NSSI • No iatrogenic effects reported • Help seeking behaviors increased (but not significantly) • Feasibility data = Very positive from school staff • NSSI acts declined (but not significantly) • Program has initial promise; more research needed Muehlenkamp, J.J., Walsh, B.W., & McDade, M. (2009). Preventing non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Support Recommendations Your Response • Be mindful of your role and position (e.g., power). • Make eye contact and speak in calm tones. • Start with your care for the student and desire to offer support. Normalize the behavior. • Focus on the desire to cope/express versus the self-injury. • Be direct and specific about your concerns and why you have them. • Balance confidence and curiosity. Let the student teach you about their experience. • Remain neutral in your responses and don’t characterize selfinjury as “bad.” – Students who self-injure may be particularly vulnerable to perceived criticism or heightened emotional response. • When a student is discussing and disclosing self-injury, prepare yourself ahead of time. Understand Triggers – Trauma related events • Flashbacks/memories • Seeing the perpetrator – – – – – – – Touch (even good touch) Family contact Self-disclosure Minimizing Problem talk Secrets Support/Help – Reaching out (no follow through) – Anxiety/Nerves – Unregulated emotions – Guilt – Shame – Sadness – Anger – Scars – Wounds/Injuries Support Plans Understand triggers. Discuss how active the self-harm is and plans to stop. Map out the students’ support system. Understanding who is good support and who is not. Assess suicide, but in a caring and non-reactive way. What helps? Journaling (usually most helpful) Expanding support system Plans, contracts (if done correctly) Harm reduction Breathing/grounding techniques Learning to set boundaries Working through trauma(s) Being overt and modeling emotional expression. Physical exercise (assess ED first) Support groups Being with someone who genuinely cares (YOU). Response DO’s • • • • • • Acknowledge the behavior as something you are familiar with Forge an alliance with the student Listen and acknowledge feelings Take their concerns seriously Respond without being directive or judgmental Create a safe and caring place for the student to talk, cry, or rant without criticism of feelings • Process with a colleague if you are worried about your response • Provide HOPE! Response DO’s • Discuss with parents/guardians … – How to establish a secure attachment with their child – The effects of repression and/or mismanagement of emotions – Stress around family secrets – Healthy and appropriate boundaries • Discussion with adolescents about... – Function or role of self-harm – Alternative coping strategies – Healthy and appropriate boundaries – Peer relationships – Social support Response DON’Ts • • • • • • • • • • React with horror or discomfort with the disclosure Ask to see the scars/wounds Immediately call a parent/guardian without other steps Ask abrupt and rapid questions Threaten or get angry Engage in power struggles and demand they stop Mandate therapy/hospitalization Accuse them of attention seeking Get frustrated if behavior continues Ignore other warning signs (i.e., family issues, suicidality) “ Don’t make the person feel worse about it. I think there is already enough shame that goes along with it. ” “ Yes, it’s that easy, if it was that easy I wouldn’t be here. Obviously it is not that easy, otherwise I would not come to YOU. ” School Protocol Example School Awareness Point person meets with the student Nurse treats (if needed) Low Risk Moderate/High Risk Some Notes About Contacting Parents/Guardians 1. Do not call without discussion with student first. Calls should never be automatic. 2. Understand home situation and make plans to call when it will not put the student at risk. A call to DHS may be more appropriate. 3. If a call to a parent/guardian makes the most sense, spend time with the student to discuss how it could go. Make a plan. Use your relationship to help them feel supported. 3. Continuously involve parents/guardians with follow ups. 4. Document parent/guardian contact and their response. Allow the student to teach YOU about their experience. They are the expert on their NSSI. Believe that you CAN be helpful.