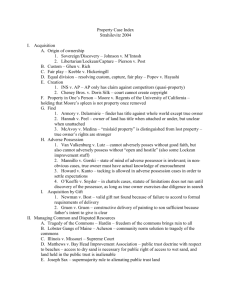

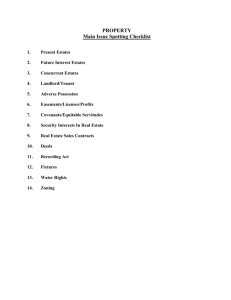

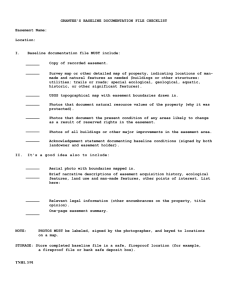

Property Outline_002

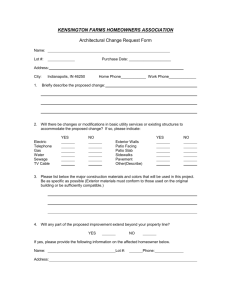

advertisement