Implications of pro-competitive reforms in the Zambian

advertisement

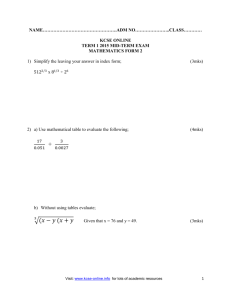

Implications of pro-competitive reforms in the Zambian maize sector on small scale farmers Cornelius Dube 4th CUTS-CIRC Biennial Competition, Regulation & Development Conference & CREW Project Final Conference Nairobi, 12-13 December 2015 Background: Maize in Zambia • Maize is the staple food for Zambia – occupies about 70% of the total cultivated land – accounts for majority of the calorie source • Important policy tool – Poverty and food security – Political power • Over the years, a number of reforms have been introduced in the maize sector • Some of the policies have a competition impact • “Competition impact” – Affecting farming – Affecting milling – Affecting maize wholesaling and retailing • The presentation focuses on ‘competition impact’ reforms, specifically on farmers’ welfare Structure overview • The central player for maize policy implementation is the Food Reserve Agency (FRA) • established in 1996, under the Zambian Food Reserve Act (1995) • FRA ensures national food security through the national strategic food reserve function – purchases agricultural crops from smallholder farmers and distributes to disadvantaged areas • Also the avenue through which input subsidies are distributed to farmers – Include subsidies to farmers (fertilizer and seed) and maize to millers (before abolishment) • FRA also determines the floor prices for maize – This is mostly the price at which farmers supply maize to FRA, which must not necessarily be the private sector buying price • Before FRA, a monopoly, NAMBOARD was in existence – before abolishment in 1989 to allow, in principle, private sector participation Summary of post liberalisation reforms Activity/Intervention Reduction in fertilizer subsidy Maize meal subsidy re-introduced before the elections Official producer and selling prices abolished Maize market opened to full competition Privatisation of the milling industry Food Reserve Agency Operational FRA subsidised to buy maize from farmers Maize and fertiliser subsidies increased Government issues export permits to selected trading/milling firms Government provides FRA with de facto monopoly on the export of maize Fertilizer and seed subsidy increased Government removes subsidies on millers Year 1991 1993 1995 1996 2002 2003 2004 2006 2008 2013 Key reforms for assessment • About 60% of agricultural expenditures has been on two maize programs – Subsidising the FRA to purchases maize at prices fixed above prevailing market prices – the farmer input support programme (FISP) that distributes subsidized fertilizer. • This makes the impact of these two programs worth assessing • Maize also powers the milling industry, who export to even neighbouring countries – the impact of the reforms on subsidised maize to maize millers also need assessment FRA Maize floor pricing • The mid 1990’s saw Zambia experiencing high variability in maize production, resulting in high price volatility • The private sector was in the initial stages of establishing itself after market liberalisation • Low prices in some areas de-motivated farmers from growing maize • Floor pricing was established generally for three main purposes – To stablise maize prices for the farmers – As a poverty reduction strategy to ensure high earnings for farmers – To ensure that farmers in remote areas also get market access • FRA’s activities raised mean maize market prices by 19%, and reduced price covariance by 36% between 2003 and 2008 • Nationally, FRA prices are always above the private sector prices Impact of the minimum floor price on farmers • The high prices benefited only the net maize sellers, but also affected the net maize buyers who faced higher prices – Net sellers comprise about 28% of all farming households – Net buyers constitute about 49% – No direct effect to about 23% of the farmers • The net sellers are mostly better off farmers who can produce more while net buyers include mostly poor farmers • Most poor households do not sell maize to the FRA – in 2003/04, only 1% of the smallholder farmers sold maize to FRA while in 2007/08 this increased to 10% • Among the buyers are urban consumers who also faced higher prices for mealie meal and maize – Especially those buying from private sector players forced to buy at high prices • Imposing above competitive prices did not necessarily promote welfare as intended Impact of floor pricing (cont..) • FRA activities also squeezed out the private sector – In some years, FRA would buy as much as 86% of the marketed surplus • This eliminated competition at buying level as FRA activities constitute an entry barrier • While FRA gets the first preference, it struggles to pay the farmers in time, affecting their preparation • Some private sector actors also compete by raising prices, becoming a cost driver for the processed products which the farmers also buy • Floor pricing thus eliminated competition, which would have been healthy for the farmer Farmer Input Support Programme • Used to be the fertiliser support programme until 2009 when sphere was expanded • The programme see farmers receiving subsidised fertiliser from govt through FRA • Mostly seen as a poverty reduction strategy tool • The FISP has a toll on government expenditure but there is no link between the FISP and poverty reduction – FISP was scaled up between 2004 - 2010 but poverty also went up • The existence of FISP meant that the private sector had little room to enter outside the FRA system • FISP failed to properly target poor farmers, as wealthier farmers also got access • Delays in input distribution under the FRA system common, at a time when private sector is crowded out • Private sector generally shuns remote areas with poor access roads – Demonstrates the importance of FRA in such regions FISP and Competition • Benefiting companies (fertiliser) are selected by the FRA through an open tender system – Nitrogen Chemical of Zambia (government owned), however, gets a predetermined allocation of the FISP • Two companies have dominated the government programme in the past; Nyiombo and Omnia. • Each of these companies has an area where they enjoy some big market share. • Omnia supplies to the maize farmers while Greenbelt supplies to the sugar plantations. • The two are now accused of cartelised behaviour of market allocation • Dominance of the two companies is often attributed to bid rigging as well • The FISP subsidised fertiliser price also stifles competition from the private sector unsubsidised fertiliser • About 33% of the fertilizer leaks into the commercial channels Maize subsidies to millers • As a poverty reduction tool, millers were roped into a subsidised maize program from FRA – It was expected that the millers would also reduce maize meal prices – The FRA also provided transport to the millers’ factories and plants • However, the difference between the inflation adjusted wholesale maize price and retail meal price actually increased – Very little of the treasury costs incurred benefited the urban consumers • Some millers were also excluded from the program – Unfair competition resulted, as some had higher production costs • Most consumers of maize rely on the services of the informal and small/medium millers, who did not benefit • Prices were not affected when the program was stopped in 2013 • The miller subsidy only distorted competition, increased millers’ revenues but had no much welfare impact on consumers Conclusion • Improperly targeted subsidies generally distort competition with little benefits to farmers • The floor pricing regime also affects farmers’ welfare negatively than intended • The public procurement systems in government programs are often subject to cartelisation, which also limits private sector participation • The miller subsidy program was rightly called off – Private sector profit orientation defeats the welfare objectives of the government – Also distorted competition by limiting beneficiaries THANK YOU !!!!!!