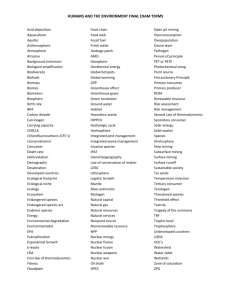

Bishop Guertin-Sirois-Toomey-Aff-New Trier

advertisement