preferences

advertisement

Intermediate Microeconomics

Preferences

1

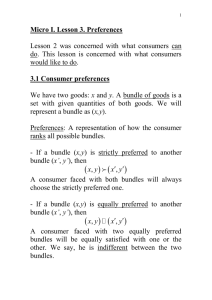

Consumer Behavior

Budget Set organizes information about possible choices

available to a given consumer.

Next step is to determine how a consumer will choose

among the bundles available in his or her budget set.

To do so, we make the seemingly obvious assumption that

individuals are rational:

Each individual chooses the bundle he or she most prefers

among all bundles available in his or her budget set.

Therefore, we first need to develop a theory of preferences,

that is both flexible and yet restrictive enough to be useful for

understanding how choices will change as the economic

environment changes.

2

Theory of Preferences

Consider again a bundle of goods denoted A-{q1A, q2A, …, qnA}

For any given individual and any given bundle A, we want to be

able to describe the following sets:

Strictly preferred set – all bundles the individual strictly prefers to A.

Weakly preferred set – all bundles the individual weakly prefers to A

(i.e. likes at least as much as A)

Any bundle not in weakly preferred set, the individual must like

strictly less than A.

3

Preferences

3 axioms in our theory of consumer

preferences

1.

2.

3.

Completeness – An individual can weakly rank

any two possible bundles.

Reflexivity – A bundle is at least as good as

itself.

Transitivity – If a bundle C is strictly preferred

to a bundle A, and an individual is indifferent

between a bundle A and another bundle D, then

the individual must also strictly prefer bundle C

to bundle D.

4

Preferences

Final common assumption - preferences exhibit

“non-satiation” or monotonicity.

Weaker version: “more can’t be worse.”

Essentially assumes free-disposal

Stronger version: “more is always better”

Certainly not true at levels (100 donuts

does me no better than 99)

For practical purposes though, not bad,

as we want to model situations where

individuals have to make choices

between things they value.

5

Preferences

Key issue we want to understand and analyze in

economics is trade-offs.

e.g. how much of one good is an individual

willing to trade-off to consume more of

another good?

Our preference axioms allow us to consider

such trade-offs via indifference curves.

For any given bundle A, there is an

indifference curve that connects A to each

bundle B where a given consumer is

indifferent between A and B.

6

Indifference Curves

Characteristics of Indifference Curves

Consider one of your indifference curves

between number of chips and ounces of Coke.

Is every possible bundle on an indifference

curve? Why or why not?

How many indifference curves are there?

If A is on a higher indifference curve than B,

what does this mean? How do we know this?

Why are indifference curves drawn with a

negative slope?

Can indifference curves cross? Why or why not?

7

Interpreting Indifference Curves

q2

Δq1

q2’

-Δq2

q1’

q1

Indifference curve indicates that at bundle {q1’,q2’},

an individual will be willing to give up Δq2 units of

good 2 to increase consumption of good 1 by Δq1.

What happens as Δq1 goes to zero?

8

Interpreting Indifference Curves

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS) –

the slope of indifference curve at a given

point.

MRS indicates an individual’s willingnessto-pay for a marginal increase of one good

in terms of the other, at a given bundle.

So how do you interpret an indifference

curve when it is very steep at a given

bundle (i.e. slope large in magnitude)?

How about when it is relatively flat?

9

Well-behaved preferences

In addition to our three Axioms and monotonicity, we will also

generally assume that weakly preferred sets are convex.

Convex preferences –

If bundles B-{q1B, q2B} and C-{q1C , q2C} are in weakly preferred set to A,

then so will the bundle {(q1B+ q1C)/2 , (q2B+ q2C)/2 }.

For example, consider the bundle {2,2}.

Suppose that for some person, both {1,3} and {4,1} are in the weakly

preferred set to {2,2}.

Then, if this person’s preferences are convex, the bundle {2.5, 2} will

also be in the weakly preferred set.

Intuition: averages are at least as good as extremes, or that individuals prefer to

have a combination of goods at moderate levels to lots of one and little of the

other (consider chips and coke)

Monotonic and Convex preferences are called well-behaved

preferences.

10

Interpreting Indifference Curves

Consider an indifference curve of following form.

q2

q

1

Does it represent convex preferences?

What does this shape reveal about MRS as q1

increases and q2 decreases?

What is intuition?

11

Interpreting Indifference Curves

Diminishing MRS

Implies an individual’s willingness to trade one good

for another diminishes the less he has of that good.

Slope of Indifference Curve “decreases” as q1

increases and q2 falls.

What is intuition?

Examples:

Chips and Coke?

Coke and a composite good?

Coke and Pepsi?

What is intuition behind different shapes of

indifference curves?

12

Interpreting Indifference Curves

Perfect substitutes - constant MRS

Perfect Complements – must consume in

fixed proportions, or individual not willing

to trade off some of one for more of

another, therefore MRS is undefined.

Examples?

What will indifference curves look like?

Examples?

What will indifference curves look like?

Are such preferences well-behaved?

13

Interpreting Indifference Curves

Consider the following indifference curves.

Are they well-behaved? Do they violate any

of our axioms?

q2

q2

q1

q2

q1

q1

14

Thinking again about assumptions over preferences

While our underlying preference axioms

and assumptions seem relatively

innocuous, they do rule out some

potentially interesting issues:

Interaction between monetary value and

preferences.

Peer effects

15

Modeling Preferences over Other Types of Goods

Suppose again you work for Doctors

Without Borders

What will your indifference curves look like

between “treating Tuberculosis patients” vs.

“treating malaria patients”?

16