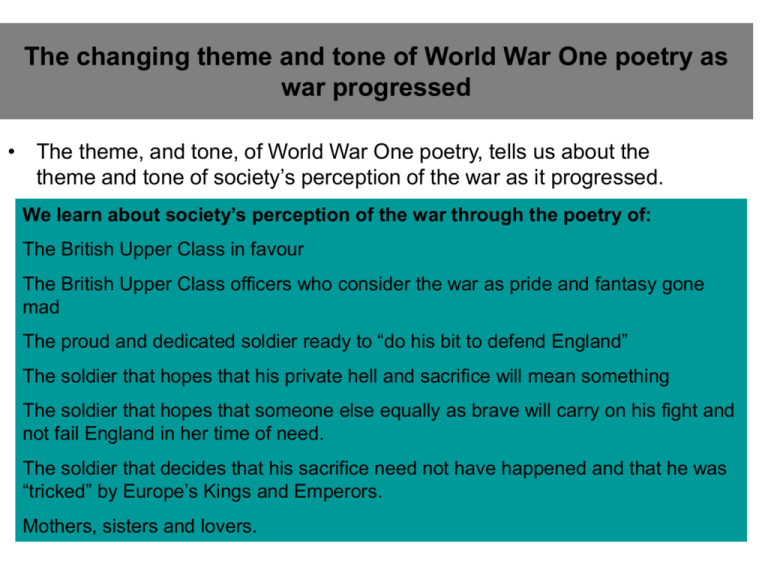

Themes of World war one poetry explains

advertisement

The changing theme and tone of World War One poetry as war progressed • The theme, and tone, of World War One poetry, tells us about the theme and tone of society’s perception of the war as it progressed. We learn about society’s perception of the war through the poetry of: The British Upper Class in favour The British Upper Class officers who consider the war as pride and fantasy gone mad The proud and dedicated soldier ready to “do his bit to defend England” The soldier that hopes that his private hell and sacrifice will mean something The soldier that hopes that someone else equally as brave will carry on his fight and not fail England in her time of need. The soldier that decides that his sacrifice need not have happened and that he was “tricked” by Europe’s Kings and Emperors. Mothers, sisters and lovers. “…All this madness, all this rage, all this flaming death of our civilisation and our hopes, has been brought about because of set of official gentlemen, living in luxurious lives, mostly stupid, and all without imagination or heart, have chosen that it should occur rather than that any one of them should suffer some infinitesimal rebuff to his country’s pride.” Bertrand Russell (1914) In his impassioned attack on the declaration of war in August 1914, the philosopher Bertrand Russell was something of a lone voice. At the time, Great Britain was riding a wave of martial and Imperial enthusiasm, and the people very much wanted conflict. Do Now:1. What does the author mean by “civilisation” in this sense? 2. Who are the “set of official gentlemen”? 3. What does having “imagination” and “heart” both mean? 4. If the set of official gentlemen had these attributes, how might things have been different? 5. What do the words infinitesimal and rebuff mean? 6. What is an impassioned attack? 7. What is a “lone voice”? 8. What does the author mean when he says that Great Britain was riding a wave of martial and imperial enthusiasm. What is martial and imperial enthusiasm? Germany had heavily remilitarised during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and began massing its army on the border with Belgium. It seemed clear that an invasion of Belgium was imminent. In response to this, British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, instructed his Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey, to issue an ultimatum: if Germany did not give Belgium an assurance of safety, then Britain would intervene on her side, and war would be declared. The deadline for this assurance was 11pm on 4 August 1914: a warm Bank Holiday weekend, in a long and pleasant summer. No such assurance was given. Crowds gathered in Trafalgar Square and outside Buckingham Palace to cheer the announcement of war. Most people believed that it would all be over by Christmas: that they were going to teach the Germans a swift lesson, and then get back to the business of running the great British Empire. They were wrong. 1. What does remilitarised, imminent and massing mean? 2. What is an ultimatum? 3. What is an assurance? 4. What does intervene mean? 5. What does the last paragraph tell us about the British view of their supremacy? Explain with evidence from the text. In the early stages poetry played a considerable part in drumming up support for the conflict. Robert Bridges was one of the poets who encouraged young men to “stand up and meet the war because the Hun is at the gate”. The Secret War Propaganda Bureau was formed and many poets wrote to support the war. For example, Laurence Binyon who wrote “For the Fallen”. Binyon did not go to war. He never came face to face with the realities of the rat and lice infested, water and mud-filled trenches. He never experienced the mixture of boredom (tedium), fear and futility: the sensation that what you were part of was a meaningless struggle begun by Europe’s leaders and supported by others who also didn’t realise the depth of the horror experienced by the soldiers on all sides of the conflict. Binyon might not have expressed the war as a “game” to be “joined”, but he did “glorify” war. He gave death and self-sacrifice the level of royalty and the highest honour. Tears are alright because they are met by the glory of God. Binyon also paints a vivid image of the soldiers being brave and “staunch” in the face of the enemy; even till their deaths. He paints them as being strong, alert and glowing with the certainty that their task was worthwhile. Binyon never saw them die in the mud, or cry for their mothers. Binyon never lived in fear for his life or his sanity. For the Fallen With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children, England mourns for her dead across the sea. Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit Fallen in the cause of the free. Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres. There is music in the midst of desolation And a glory that shines upon our tears. They went with songs to the battle; they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted; They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old; Age shall not weary them, not the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them. 1. In what ways has Binyon given the soldiers religious or biblical heroic attributes? Explain with examples. 2. In what ways has Binyon given the struggle and hardship the highest honour? Explain with examples. 3. In what ways has Binyon shown that the soldiers were unfailingly strong and unfailingly good young people. Explain with examples. 4. What is it about the theme and tone of Binyon’s poem we hold onto today. When and Why? Rupert Brooke was another poet that wrote about the war being a place of “heroic” sacrifice. He was ambivalent about the conflict to begin with, but joined up and threw himself into thoughts and dreams of achieving military “glory”. Like so many of his upper class, his generation and schooling, he looked at the war with pride and necessary sacrifice. Brooke saw a little bit of conflict, but as he died in 1915 of blood poisoning on his ship in the Greek islands, his poetry never moved away from the fantasy of war being glory and sacrifice. He became known as a war hero when he died and his poems were used by propagandists to promote the conflict in England because they celebrated the idea of giving one’s life for one’s country. Peace, by Rupert Brooke Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with his hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power, To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping, Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary, Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move, And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary, And all the little emptiness of love! 1. Who does Brooke thank for the opportunity that war brings? Include the quote. 2. What does he see himself and other young gentlemen like? Include the quote. 3. What does Brooke mean about into cleanness leaping? What is this cleanness? 4. What does he think of those who have not joined the war voluntarily? What attribute does he think they lack? Brooke also considered that the sacrifice of war was a rebirth; a baptism or a chance for redemption, absolution or forgiveness of sins committed in this life-time. The war’s CONFLICT has given the opportunity for EMOTIONAL PEACE!!!!!!! I’d like to know what he did! Check the second half of “Peace” out and a line in “The Soldier”. Oh! We, who have known shame, We have found release there, Where there’s no ill, no grief, but sleep in mending, Naught broken save the body, lost but breath; Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there But only agony, and that has ending; And the worst friend and enemy is but death. And think, this heart, all evil shed away,… 1. What is Brooke being released from? 2. Do people do this today? Do they use conflict around them, or business to take their minds of stuff that bugs them? Explain with an example. 3. The ultimate arrival at “peace” for Brooke appears to be death. What does Brooke call death? 4. According to Brooke, what is the soldier who sacrificed himself in WWI like, when he goes to heaven? Provide an example. In the Dordogne, by John Peele Bishop If any question why we died …And each day one died or another died: each week we sent out thousands Tell them, because our fathers lied. That returned by hundred A Dead Statesman (politician) Wounded or gassed. And those that died Common Form, by Rudyard Kipling I could not dig; I dared not rob; We buried close to the old wall… Therefore I lied to please the mob. Now all my lies are proved untrue And I must face the men I slew. What tale shall serve me here among Mine angry and defrauded young? And because we had courage; Because there was courage and youth ready to be wasted; because we endured and were prepared for all the endurance; we thought something must come of it:… What did the soldiers have to say now? Report on Experience, by Edmund Blunden I have been young, and now am not too old; And I have seen the righteous forsaken (innocent men, defrauded and sacrificed) His health, his honour and his quality taken. This is not what we were formerly told. I have seen a green country, useful to the race, Knocked silly with guns and mines, its villages vanished, Even the last rat and kestral banished… Preparations for Victory …Days or eternities like swelling waves Surge on, and still we drudge in this dark maze… 1. What does the soldier think/see that war has done to other soldiers? 2. What does the soldier see has happened to Europe? 3. Blunden uses simile to compare what to growing ocean waves? 4. What is the dark maze – literally and metaphorically? In contrast to this style of World War One poetry we have poets who reflect the realisation that the conflict is meaningless. That it was sending young men off to die for the pointless national pride of kings and emperors that lived in worlds disconnected from reality. They had the means to destroy another’s nation – but were not concerned about the individuals and their families that were carrying out their commands. Their countries were tearing each other apart – just because they could. They had the boats, the guns and the foot soldiers. Lament, by F.S Flint. The young men of the world Are condemned to death. They have been called up to die For the crime of their fathers. 1. How does this piece compare to Rupert Brooke’s PEACE?: Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with his hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power, To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping, Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary, Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move, And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary, And all the little emptiness of love! Lament continued…The young men of the world, The growing, the ripening fruit, Have been torn from their branches, While the memory of the blossom Is sweet in women’s hearts; They have been cast for a cruel purpose Into the mashing-press and furnace. Lament continued… The young men of the world Look into each other’s eyes, And read there the same words: Not yet! Not yet!... How does this compare to Binyon’s For the Fallen: How does this verse compare to: …Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres. There is music in the midst of desolation And a glory that shines upon our tears… …They went with songs to the battle; they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted; They fell with their faces to the foe…? They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old; Age shall not weary them, not the years condemn.? The young men of the world No longer possess the road: The road possesses them. They no longer inherit the earth; The earth inherits them. They are no longer the masters of fire: Fire is their master; They serve him, he destroys them. They no longer rule the waters” The genius of the seas Has invented a new monster, And they fly from its teeth. They no longer breathe freely: The genius of the air Has contrived a new terror That rends them into pieces. The young men of the world Are encompassed with death He is all about them In a circle of fire and bayonets. Weep, weep, o women, And old men break your hearts. 1. What does Flint have to say about the soldiers control over their futures? 2. What does he have to say about the advancement of man? 3. What is the “new monster of the seas”? 4. What two things make up the “genius of the air”? How does the last verses compare with this piece of Binyon’s For the Fallen With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children, England mourns for her dead across the sea. Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit Fallen in the cause of the free…? Valley of the Shadow, by John Galsworthy God, I am travelling out to death’s sea, I, who exulted in sunshine and laughter, Dreamed not of dying – death is such waste of me! Valley of the Shadow contin… Grant me one prayer: Doom not the hereafter Of mankind to war, as though I had not not – I who, in battle, my comrade’s arm linking, How does this compare to Brooke’s PEACE Shouting and sang – life in my pulses hot… …Naught broken save the body, lost but breath; Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there But only agony, and that has ending; And the worst friend and enemy is but death…? Let not my sinking In dark be for naught, my death a vain thing! God, let me know it the end of man’s fever!... 1. What does this soldier plea for? Breakfast, by Wilfred Gibson I cannot sleep, I cannot think, We ate out breakfast lying on our backs but only gaze upon the glass Because the shells were screeching overhead. Of water that he could not drink. I bet a rasher to a loaf of bread That Hull United would be Halifax when Jimmy Stainthorpe played full-back instead Of Billy Bradford. Ginger raised his head And cursed, and too the bet, and dropt back dead. We ate our breakfast lying on our backs Because the shells were stretching overhead. Mark Anderson, Wilfred Gibson On the low table by the bed Where it was set aside last night, Beyond the bandaged lifeless head, It glitters in the morning light; And as the hours of watching pass, 1. What is the tone of “Mark Anderson”? 2. What is the tone of “Breakfast”? The Target, by Ivor Gurney I shot him, and it had to be One of us! ‘Twas him or me. “Couldn’t be helped” and none came blame Me, for you would do the same. My mother, she can’t sleep for fear Of what might be a –happening here To me. Perhaps it might be best To die, and set her fears at rest…. All’s a tangle. Here’s my job. A man might rave, or shout, or sob; And God He takes no sort of heed. This is a bloody mess indeed. 1. Who was the target? 2. Who could it have easily been? 3. What does the soldier think would be best to happen? 4. Does the soldier think that God cares about them? Explain with an example. The Silent One, by Ivor Gurney Who died on the wires, and hung there, Nothing but chance of death, after tearing of clothes One of two – Kept flat, and watched the darkness, Who for his hours of life had chattered through Hearing bullets whizzing – Infinite lovely chatter of Bucks accent: And thought of music – and swore… Yet faced unbroken wires; stepped over, and went A noble fool, faithful to his stripes – and ended. But I weak, hungry, and willing only for the chance Of line – to fight in the line, lay down under unbroken Wires, and saw the flashes and kept unshaken, Till the politest voice – a finicking accent, said: “Do you think you might crawl through, there: There’s a hole.” Darkness, shot at: I smiled, as politely replied – “I’m afraid not, Sir.” There was no hole No way to be seen. The Deserter, by Winifred M. Letts There was a man – don’t mind his name, Whom Fear had dogged by night and day. He could not face the German guns And so he turned and ran away, But who can judge him, you or I? God makes a man of flesh and blood Who yearns to live and not to die. And this man when he feared to die Was scared as any frightened child… A man in abject hear of death; But fear had gripped him, so had death;… They shot him when the dawn was grey. Blindfolded, when the dawn was grey, He stood there in a place apart, The shots rang out and down he fell. An English bullet in his heart! 1. What does Letts tell us about deserters? Give three points, with explanations and examples from the text. Suicide in the Trenches, by Siegfried Sassoon I knew a simple soldier boy Who grinned at life in empty joy, Slept soundly through the lonesome dark, And whistled early with the lark. In winter trenches, cowed and glum, With crumps and lice and lack of rum, He put a bullet through his brain. No one spoke of him again. You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye Who cheer when solder lads march by, Sneak home and pray you’ll never know The hell where youth and laughter go. 1. Sassoon was a British officer in the army. Name two emotions expressed by Sassoon in this poem. Provide examples of their existence by finding text from the poem to support them. The Soldiers Come Home… Survivors, by Siegfried Sassoon No doubt they’ll soon get well; the shock and strain Have caused their stammering, disconnected talk. Of course they’re “longing to go out again” – These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk. They’ll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died – Their dreams that drip with murder; and they’ll be proud Of glorious war that shatter’d all their pride… Men who sent out to battle, grim and glad; Children, with eyes that hate you, broken and mad. 1. What do the doctors expect will happen to the soldiers home on rehabilitation leave? 2. What does Sassoon believe about the Survivors? 3. Who are the “children”? Does it Matter? By Siegfried Sassoon Does it Matter? – losing your legs? For people will always be kind, And you need not show that you mind When others come in after hunting To gobble their muffins and eggs. Does it matter? – losing your sight? There’s such splendid work for the blind; And people will always be kind, As you sit on the terrace remembering And turning your face to the light. Do they matter? – those dreams in the pit? You can drink and forget and be glad, And people won’t say that you’re mad; For they know that you’ve fought for your country, And no one will worry a bit. 1. What is the tone of Sassoon’s poem? Explain why you think this and provide examples from the text. A War Film, by Teresa Hooley It should be taken away I saw, And with a catch of the breath and the heart’s uplifting, To war. Tortured. Torn. Sorrow and pride, the “week’s great draw” – Slain The Mons Retreat; Rotting in No Man’s Land, …As in a dream, Out in the rain – Still hearing the machine-guns rattle and shells scream, My little son… I came out into the street. Yet all those men had mothers, every one. When the day was done, My little son Wondered at bath-time why I kissed him so, How should he know Why I kissed and kissed and kissed him, crooning his name? …How could he know The sudden terror that assaulted me?... He thought that I was daft. The body I had borne He thought it was a game, Nine months beneath my heart, And laughed, A part of me… And laughed. If, someday,