WattsSEDU7006-8-5Graded - Steve's Doctoral Journey HOME

advertisement

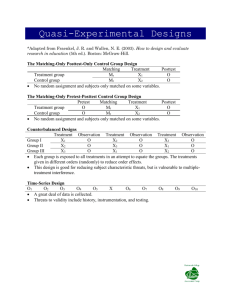

WattsSEDU7006-8-5 0 Quasi-experimental Design Stephen W. Watts Northcentral University WattsSEDU7006-8-5 1 Quasi-experimental Design Jackson (2012) Chapter Exercises #2. The psychology professor has two sections of students that were not randomly assigned. The treatment will be weekly quizzes. The desired outcome is improved student learning. I will assume that student learning is measured by the total score on all exams not including the weekly quizzes. This design can be diagrammed with the following notation: N X N O O Based on these assumptions I would recommend a nonequivalent control group posttest only design for this quasi experiment. If student learning is measured by scores on major exams through the course, however, the notation changes, as would the recommendation. The following notation represents an alternative possibility for this design: N N X O O X O O Based on these assumptions, I would recommend a nonequivalent control group time-series design for this experiment. Overall, this later design is a stronger design because of the multiple observations and points of comparison between the two sections. #4. Usually the nonequivalent control group design uses intact groups. Since these groups are not randomly selected, the major confound for this design is selection bias. Selection bias arises when the control and experimental groups are not comparable before the study and gives an alternative explanation for any differences in the posttest. In this design there are a couple of social interaction threats that are possible. Students in the experimental section may WattsSEDU7006-8-5 2 find out that students in the control section are not getting quizzes and react negatively, causing resentful demoralization, or react competitively, causing compensatory rivalry. Either case would tend “to equalize the outcomes between groups, minimizing the chance of seeing a program effect even if there is one” (Trochim & Donnelly, 2008, p. 171). A single-group design’s worst confound is that there is no comparison group, therefore, if student scores are high or low, it is impossible to tell if they are that way because of the treatment, or because of some alternative explanation. With only a single group to measure, all of the single group threats to internal validity are possible. In this particular study the most likely would be a history threat, where an event or set of events could affect the outcome more than the treatment. #6. Three reasons a researcher might choose a single-case design include, (a) when a single person or condition is of interest, (b) when replication of results is essential, and (c) situations in which error variance needs to be eliminated (Jackson, 2012). Clinical trials often are interested in the effect of a treatment on a single individual. One study was interested in mitigating or eliminating auditory hallucinations and delusions as a result of schizophrenia, and evaluated the use of “an innovative rational-emotive cognitive treatment” (Qumtin, Belanger, & Lamontagne, 2012, p. 114). From this treatment there was a noticeable and immediate reduction in depression and anxiety and an increase in the patient’s quality of life that extended through the 12-month follow up. A discussion regarding replication of empirical results resulting from single-case designs in psychology and education was written by Kratochwill and Levin (2010) along with suggestions for improving the credibility of these designs by using randomization. Error variance results from differences between participants in a group. In a single-case design WattsSEDU7006-8-5 3 there is no group, hence no error variance; making the determination of outcomes resulting from the independent variable much less complicated. #8. Single case designs can be implemented in a number of ways. In a reversal design the focus is on a single participant, a single behavior, or a single situation, and involves the independent variable being applied and removed one or more times to assess its impact. By evaluating the behavior without the treatment applied and then comparing the behavior after treatment, a determination can be made regarding the treatments effect. Succeeding periods of non-treatment are called the reversal and can demonstrate what happens to the behavior with a return to the baseline. A reversal design is very similar to a within-subjects group design because each subject experiences both the control and experimental condition. Greenhoot (2003) summarized that the reversal of an effect because of the removal of a treatment provided “strong evidence for a causal link between the independent and dependent variable” (p. 98). In a multiple-baseline design multiple participants, behaviors, or situations may be involved. In these single case studies the measures of interest are individualized and descriptive statistics are not used to aggregate them. The multiple-baseline design measures the effect of the application of a treatment at differing times for multiple subjects, or can be used with a single subject by applying the treatment in conjunction with different behaviors or in different scenarios. Part I Assignment Question Answers Describe the advantages and disadvantages of quasi-experiments? What is the fundamental weakness of a quasi-experimental design? Why is it a weakness? Does its weakness always matter? A quasi-experimental design has certain advantages, including; (a) the ability to “draw slightly stronger conclusions than . . . with correlational research” (Jackson, WattsSEDU7006-8-5 4 2012, p. 342), (b) contributing original research to the body of knowledge in a field (Ellis & Leavy, 2011), (c) allowing real-world research in the field as opposed to more controlled conditions (Jackson, 2012), (d) may involve an independent variable that is nonmanipulated (Hoadley, 2004), and (e) can be used with intact groups (de Anda, 2007). The disadvantages of using a quasi-experimental design are that (a) it “limits internal validity in a study” (Jackson, 2012, p. 342), (b) does not establish a causal relationship between variables (Jackson, 2012), while (c) probabilistic equivalence cannot be assumed (Dimitrov & Rumrill, 2003). The fundamental weakness of a quasi-experimental design, and what makes it “quasi”, is that it does not involve random assignment of participants to experimental conditions (Greenhoot, 2003). Nonrandom assignment weakens internal validity, diminishes the ability to establish cause-andeffect by eliminating the expectation that groups are equivalent. This weakness does not exclude quasi-experiments from a researchers arsenal because of the advantages mentioned above. These advantages make quasi-experiments the most used form of quantitative research (Ellis & Leavy, 2011). There may be times when subjects cannot be randomly assigned to groups, there is only one subject of interest, or the topic of research either exists or it does not; in all of these cases a quasi-experiment is a viable option for conducting the research while an experiment is not (Greenhoot, 2003). If you randomly assign participants to groups, can you assume the groups are equivalent at the beginning of the study? At the end? Why or why not? If you cannot assume equivalence at either end, what can you do? Please explain. If participants are randomly assigned to groups from the same population of interest to the study, the groups can be said to be probabilistically equivalent at the beginning of a study (Trochim & Donnelly, 2008). Random assignment does not ensure groups are exactly the same, but that differences between WattsSEDU7006-8-5 5 the groups can be statistically determined since “groups can differ only due to chance assignment” (p. 189). If, however, participants are chosen from a pool that does not represent the study population, or from multiple pools with differing characteristics, they will neither be equivalent or probabilistically equivalent. Assigning subjects to control and experimental groups randomly is the best means of ensuring probabilistic equivalence at the beginning of a study, as long as the subjects are chosen from the appropriate population. Even though the groups will not be exactly the same, the probability that they are different can be calculated and minimized. There are also designs that allow for the use of the same participants in both control and experimental conditions, ensuring equivalence between conditions. Whether groups are probabilistically equivalent at the end of a study is the purpose of research. In a perfect world, where the treatment has an effect, the experimental group will consist of a different population from the control group at the end of a study, and this difference is the treatment effect. Unfortunately, there are confounds other than the application of the treatment that may exacerbate or minimize differences between the groups, consisting of the threats to internal validity. The best way to ensure that the only conditions that change between the groups is by designing the experiment to minimize threats to internal validity. By demonstrating that an independent variable precedes the dependent variables, and that they covary together, while showing that there are no other plausible explanations for the relationship, internal validity is high and can explain causality. With a properly designed study, the first two criterion are easy to control so it is critical to focus on the third criteria, and minimize alternative explanations. WattsSEDU7006-8-5 6 Explain and give examples of how the particular outcomes of a study can suggest if a particular threat is likely to have been present. Trochim and Donnelly (2008) identified five possible outcomes for a research study and the potential internal validity threats associated with each outcome. They noted that the crossover pattern has the “clearest pattern of evidence for the effectiveness of the program of all five of the hypothetical outcomes” (p. 215) and that there are no plausible threats to internal validity. In this particular pattern the control group does not appear to change from pretest to posttest, but the pretest of the experimental group has a lower score than the control, while the posttest score of the experimental group is higher than that of the control group. Two patterns identified by Trochim and Donnelly (2008) have the control and experimental groups close in score on the pretest, which I will label as diverging patterns. In the first diverging outcome pattern, the control group maintains a consistent pretest-posttest score, while the treatment group’s??? score increases from pretest to posttest. The most likely internal validity threat presented in this situation is a selection-history threat where an event occurs to which the treatment group reacts and the control group does not. The second diverging outcome pattern reflects improvement in scores for both groups between pretest and posttest, but the treatment group improves more. Because of the improvement in scores by both groups almost all of the multiple-group threats to internal validity are possible, with the exception of selectionregression. Improvements by both groups can indicate selection-maturation, selection-history, selection-testing, and selection-instrumentation as possible threats that affected the scores. Two patterns identified by Trochim and Donnelly (2008) have the control and experimental groups close in score on the posttest, which I will label as converging patterns. In the first converging outcome pattern the two groups begin far apart on pretest scores, with the WattsSEDU7006-8-5 7 experimental group being much higher than the control group, and end with both groups’ posttest scores close together. The second converging outcome pattern is similar except in this case the pretest scores are much lower for the experimental group, and in the posttest the control and experimental scores are close together. In both cases, the control group remains consistent between pretest and posttest scores, while the experimental groups vary greatly and approach the scores of the control group. The most likely threat to internal validity in the converging scenarios is selection-regression. Participants may have been selected because of high or low scores on a measure, and even though the treatment may or may not have had an effect, the scores are closer to the mean. Describe each of the following types of designs, explain its logic, and why the design does or does not address the selection threats discussed in Chapter 7 of Trochim and Donnelly (2006): a. Non-equivalent control group posttest only. The nonequivalent control group posttest only design has at least two nonrandomly selected groups. One of the groups is the experimental group and will be administered the new treatment, while the other group is the control group and will have no treatment, or the standard treatment. If the two groups can be shown to be relatively equivalent the results of this design are very similar to a true experiment, and the comparison between the groups on the posttest should reflect the effect of the treatment (Jackson, 2012). The problem with this design is that it allows very little within the design to determine if the groups are roughly equivalent in the first place, meaning that “you can never be sure the groups are comparable” (Trochim & Donnelly, 2008, p. 211). This means that the design is especially susceptible to selection bias since the groups are not randomly selected, and the groups may not be equivalent. It is possible using this design that the two groups could have different history or WattsSEDU7006-8-5 8 maturation during the duration of the program that could impact the posttest, but none of the other multiple-group threats to internal validity are applicable for this design. If participants of each group are not isolated from each other there is also the possibility of the social interaction threats to internal validity; diffusion or imitation of treatment, compensatory rivalry, or resentful demoralization (Trochim & Donnelly, 2008). b. Non-equivalent control group pretest/posttest. The nonequivalent control group pretest/posttest design has at least two nonrandomly selected groups. One group comprises the experimental group, and receives treatment, while the other group is the control group, receiving no treatment or the standard treatment. Each group receives a measure regarding the dependent variables at the beginning of the study, and then another equivalent measure regarding the dependent variables at the end of the study. The addition of the pretest allows the researcher to compare the groups with respect to the dependent variables to determine whether the groups are roughly equivalent. If the groups are equivalent the internal validity of the posttest comparison is increased, and if they are not the posttest scores can be statistically adjusted based on the pretest scores. c. Cross-sectional. A cross-sectional design studies multiple strata of a population at the same time. For example, a cross-sectional design focused on writing development may sample from 7th, 9th, and 11th grade students. The logic behind a cross-sectional study is to collect as much data regarding the stratum as quickly as possible. This study often does not adequately address selection bias, since the subjects are by definition stratified around some criteria that distinguishes them from the other strata. d. Regression-Discontinuity. The regression-discontinuity design begins by administering a pretest to all participants, and then relegates them to control or experimental groups based on a WattsSEDU7006-8-5 9 specific cutoff score. Those with the greatest need for treatment are administered the treatment, while the other group serves as a control. Unlike randomized experiments this design makes no attempt to equalize the groups. While in other designs nonequivalence is damaging to internal validity, in a regression-discontinuity design it serves to strengthen the internal validity. The reason for this is that the groups are intentionally designed to not be equivalent, but instead have a linear relationship with each other. If during the posttest there is still a linear relationship between the groups, the treatment had no effect. However, if there is a discontinuity between the groups at the point of cutoff, a gap between each group’s linear representations of scores, this indicates the effect of the treatment. This design addresses all threats to internal validity from multiple groups, but can still be affected by social interaction threats that will tend to diminish the effect size. Why are quasi-experimental designs used more often than experimental designs? Quasi-experimental designs are often used when it is not feasible or ethical to conduct a randomized controlled study (Trochim & Donnelly, 2008). For example, in education research the general desire is to know how some treatment affects students in the classroom. In most cases if an experiment is going to be conducted in a classroom setting, students cannot be randomly selected by teachers for inclusion into an experimental and control group. Thus, for the majority of educational studies it is not feasible to randomize. Further, if a treatment is known to be efficacious, it is unethical to withhold that treatment from certain individuals while providing it to others. Most medical research chooses quasi-experimental designs for this reason (Harris et al., 2006). One conclusion you might reach (hint) after completing the readings for this assignment is that there are no bad designs, only bad design choices (and implementations). WattsSEDU7006-8-5 10 State a research question for which a single-group post-test only design can yield relatively unambiguous findings. Many training classes use this very design. At the culmination of the training an evaluation is presented to the students and they are requested to fill it out, depicting their satisfaction with various factors regarding the course. Students could not very well be satisfied with or express how much they learned from the class at the beginning of the class, so in this situation a pretest would make little sense. Part II Assignment Question Answers What research question(s) does the study address? Research questions are designed to determine relationships between variables. In this study there were two independent variables, identified as income level of parents, and exposure time to children’s TV commercials. One research question for this study could have been: Among pre-pubescent children, how effective are commercials directed toward them at product recognition? Another research question could have been: What effect does parent’s income level have on the amount of time children view TV? What is Goldberg’s rationale for the study? Was the study designed to contribute to theory? Do the results of the study contribute to theory? For both questions: If so, how? If not, why not? Goldberg’s (1990) rationale for conducting the quasi-experiment was three-fold. First, Goldberg identified that “research using an experimental paradigm has tended to support the view that the influence of commercials targeted at children is considerable” (p. 445, emphasis in original) and gave a number of examples. Second, Goldberg demonstrated that “much of the research stream that has utilized a survey research/correlational paradigm to study the effects of advertising on children tends to indicate that advertising has a fairly minor role in influencing measures such as children’s preferences” (p. 446, emphasis in original). Third, Goldberg WattsSEDU7006-8-5 11 identified that others had “noted the need to combine the two approaches” (p. 446) and proposed a quasi-experiment as a way to have “some of the advantages of both the experimental and survey methods” (p. 446) to determine the effect of advertising directed toward children. The study was designed to contribute to theory because Goldberg (1990) continued to test whether advertising directed towards children is efficacious. To this point, the literature was inconclusive regarding the effect of advertising on children due to a divergence between outcomes gathered through experimental versus case studies. If advertising geared toward children is ineffectual, companies need to determine a better and more effective use of their advertising dollars. The applicable theory in this study is advertising theory; the assumptions and principles that encourage people to buy products. This framework is subdivided in this study, focusing on children and how commercials directed towards them impacts their recognition of and desire to obtain certain products. The results of Goldberg’s (1990) study did contribute to theory. The outcomes indicated that children with minimal to no exposure to commercials targeting them were much less likely to recognize advertised products, or have them in their homes. On the other hand, children with more exposure to advertising were shown to be more likely to recognize certain products and to have them in their homes. This study corroborates much of the experimental research regarding the effectiveness of advertising on children and contributes to advertising theory. What constructs does the study address? How are they operationalized? The main construct in Goldberg (1990) is advertising. Is advertising to children effective? Advertising as a construct was operationalized in the study through statistics regarding what is advertised to children. Since, “the most prevalent product categories advertised to children are toys . . . and foods” (p. 448) these were chosen as a way to determine the effectiveness of the advertisements. WattsSEDU7006-8-5 12 Further, one-quarter of the foods marketed toward children are breakfast cereals, so “children’s toys and cereals were selected as the focus of the study” (p. 448). A moderating construct was created in the study based on income level. Since some of the children’s parents’ income level was unavailable, this construct was operationalized by collecting the children’s mothers and fathers occupation. Another construct that was utilized in the study was exposure time to French-based and English-based TV stations by using a survey to determine which shows were watched when. By calculating how often shows were watched, the researchers were able to “estimate the total number of [American children’s commercial TV] programs each child watched during the year” (p. 448). What are the independent and dependent variables in the study? The independent variables in Goldberg’s (1990) study were “cultural affiliation as defined by the language spoken” (p. 448), “the total number of ACTV programs each child watched during the year” (p. 448), and family income as differentiated by parental occupations. Goldberg’s dependent variables consisted of recognition of toys and breakfast cereals that were marketed on American TV. Name the type of design the researchers used. Goldberg (1990) used a nonequivalent control group posttest only quasi-experimental design for the main focus of this study. What internal and external validity threats did the researchers address in their design? How did they address them? Are there threats they did not address? If so how does the failure to address the threats affect the researchers’ interpretations of their findings? Are Goldberg’s conclusions convincing? Why or why not? Conducting each groups survey at one time, and gathering surveys from different socio-economic groups in disparate locations, the threats to internal validity through social interaction were eliminated or minimized. The study WattsSEDU7006-8-5 13 consisted of multiple groups, eliminating the single group threats to internal validity. With multiple groups there is only a single threat to internal validity; that of selection bias (Jackson, 2012). By taking the surveys at one time for each group, and not having a pre-test the selection threats of testing, instrumentation, mortality, and regression were eliminated. With all surveys for all groups taken within a two-week period the selection threat of maturation was minimized or eliminated. The only remaining threat to internal invalidity is history; there could have been some event that occurred between the surveys taken in the schools and the surveys taken in the camps that may have affected the later collection. Goldberg (1990) addressed the threat of history by using a t-test to determine if there were any significant differences between the groups with regards to the dependent measures, and there were not. External validity addresses the generalizability of a study. For this study the major threat to external validity was that the groups were not randomly selected into the control and experimental groups. Goldberg (1990) raised the issue that an alternative explanation for the results may be “due to cultural differences between the two groups” (p. 453). Goldberg attempted to address this issue by comparing the dependent variables with the independent variables within-groups, finding that “at comparable levels of ACTV viewing, English- and French-speaking children purchased equivalent numbers of children’s cereals” (p. 453). He admits, however, that in regards to the recognition of toys “other factors . . . may have contributed to the observed difference in toy awareness levels between English- and Frenchspeaking children” (p. 453). Goldberg’s (1990) conclusions are reasonably convincing, but there are limitations. The study shows that there is a difference between the language groups, and his rationale regarding the children’s access to commercials geared toward them is appealing. A major weakness to the WattsSEDU7006-8-5 14 overall conclusion is that he only compares children within the single province of Quebec, and admits that differences in recognition could be the result of cultural factors, and he does not proceed to the next logical step of showing whether recognition of toys is the same as buying them. So, I am willing to accept that advertising directed toward children is effective at garnering brand recognition; I cannot find support that the legislation “appears to have reduced consumption of those cereals” (p. 453). Nowhere in his study did Goldberg have provisions for comparing current consumption with past consumption. Further, his conclusion that reduced exposure to toy commercials “would leave children unaware of the toys and thus less able to pressure their parents to buy them” (p. 453) is not warranted by his study, since he tested recognition only, but failed to determine if this recognition translated into “pressure” on parents to buy more toys. WattsSEDU7006-8-5 15 References de Anda, D. (2007). Intervention research and program evaluation in the school setting: Issues and alternative research designs. Children & Schools, 29(2), 87-94. Retrieved from ERIC Database. (EJ762838) Dimitrov, D. M., & Rumrill, P. D. Jr. (2003). Pretest-posttest designs and measurement of change. Work, 20(2), 159-165. Retrieved from http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCoQFj AA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.phys.lsu.edu%2Ffaculty%2Fbrowne%2FMNS_Semina r%2FJournalArticles%2FPretest-posttest_design.pdf&ei=Z0V1T4rLJ8Wi2gXummUDQ&usg=AFQjCNF6-c4j-7JJKm9ohkXr6jXJ1T7pA&sig2=BW7hMizEWzQBfgUIIQ30rA Ellis, T. J., & Levy, Y. (2011). Framework of problem-based research: A guide for novice researchers on the development of a research-worthy problem. Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 11(1), 17-33. Retrieved from http://inform.nu/Articles/Vol11/ISJv11p017-033Ellis486.pdf Goldberg, M. E. (1990). A quasi-experiment assessing the effectiveness of TV advertising directed to children. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(4), 445-454. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3172629 Greenhoot, A. F. (2003). Desgin and analysis of experimental and quasi-experimental investigations. In M.C. Roberts & S. S. Ilardi (Eds.), Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology (p.92-114). doi:10.1002/9780470756980.ch6 Harris, A., McGregor, J. C., Perencevich, E. N., Furuno, J. P., Zhu, J., Peterson, D. E., & Finkelstein, J. (2006). The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, 13(1), 16-23. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1749 Hoadley, C. (2007). Learning sciences theories and methods for e-learning researchers. In R. Andrews, & C. Haythornthwaite (eds.), The SAGE handbook of e-learning research (pp. 139-156). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. Jackson, S. L. (2012). Research methods and statistics: A critical thinking approach (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. Kratochwill, T. R., & Levin, J. R. (2010). Enhancing the scientific credibility of single-case intervention research: Randomization to the rescue. Psychological Methods, 15(2), 124144. doi:10.1037/a0017736 Qumtin, E., Bélanger, C., & Lamontagne, V. (2012). A single-case experiment for an innovative cognitive behavioral treatment of auditory hallucinations and delusions in schizophrenia. International Journal Of Psychological Studies, 4(1), 114-121. doi:10.5539/ijps.v4nlp114 WattsSEDU7006-8-5 16 Trochim, W. M. K., & Donnelly, J. P. (2008). The research methods knowledge base (3rd ed.). Mason, OH: Cengage Learning.