Indirect hernia - Dis Lair

advertisement

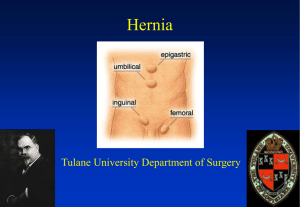

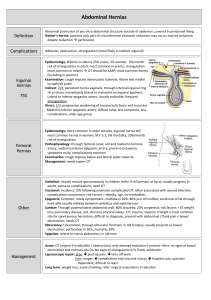

Hernias Background As defined in 1804 by Astley Cooper, a hernia as a protrusion of any viscus from its proper cavity. The protruded parts are generally contained in a sac-like structure, formed by the membrane with which the cavity is naturally lined.1 Since that time, several different types of abdominal wall hernias have been identified, along with a larger number of associated eponyms. This article reviews the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of most of these hernias from an emergency medicine perspective. Hernias are brought to the attention of an emergency physician either during a routine physical examination for other medical complaints or when the patient has developed a complication associated with the hernia. Pathophysiology Types of Hernia - Location Indirect hernia An indirect inguinal hernia follows the tract through the inguinal canal. This results from a persistent process vaginalis. The inguinal canal begins in the intra-abdominal cavity at the internal inguinal ring, located approximately midway between the pubic symphysis and the anterior iliac spine. The canal courses down along the inguinal ligament to the external ring, located medial to the inferior epigastric arteries, subcutaneously and slightly above the pubic tubercle. Contents of this hernia then follow the tract of the testicle down into the scrotal sac. Direct hernia A direct inguinal hernia usually occurs due to a defect or weakness in the transversalis fascia area of the Hesselbach triangle. The triangle is defined inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, laterally by the inferior epigastric arteries, and medially by the conjoined tendon.5 Femoral hernia The femoral hernia follows the tract below the inguinal ligament through the femoral canal. The canal lies medial to the femoral vein and lateral to the lacunar (Gimbernat) ligament. Because femoral hernias protrude through such a small defined space, they frequently become incarcerated or strangulated.6 Umbilical hernia The umbilical hernia occurs through the umbilical fibromuscular ring, which usually obliterates by 2 years of age. They are congenital in origin and are repaired if they persist in children older than age 2-4 years.2,5 Richter hernia The Richter hernia occurs when only the antimesenteric border of the bowel herniates through the fascial defect. The Richter hernia involves only a portion of the circumference of the bowel. As such, the bowel may not be obstructed, even if the hernia is incarcerated or strangulated, and the patient may not present with vomiting. The Richter hernia can occur with any of the various abdominal hernias and is particularly dangerous, as a portion of strangulated bowel may be reduced unknowingly into the abdominal cavity, leading to perforation and peritonitis.6 Incisional hernia This iatrogenic hernia occurs in 2-10% of all abdominal operations secondary to breakdown of the fascial closure of prior surgery. Even after repair, recurrence rates approach 20-45%. Spigelian hernia This rare form of abdominal wall hernia occurs through a defect in the spigelian fascia, which is defined by the lateral edge of the rectus muscle at the semilunar line (costal arch to the pubic tubercle).7,8 Obturator hernia This hernia passes through the obturator foramen, following the path of the obturator nerves and muscles. Obturator hernias occur with a female-to-male ratio of 6:1, because of a gender-specific larger canal diameter. Because of its anatomic position, this hernia presents more commonly as a bowel obstruction than as a protrusion of bowel contents.1 Types of Hernia - Condition 1. Reducible hernia: This term refers to the ability to return the contents of the hernia into the abdominal cavity, either spontaneously or manually. 2. Incarcerated hernia: An incarcerated hernia is no longer reducible. The vascular supply of the bowel is not compromised. Bowel obstruction is common. 3. Strangulated hernia: A strangulated hernia occurs when the vascular supply of the bowel is compromised secondary to incarceration of hernia contents. Etiology The embryology of the groin and of testicular descent largely explains indirect inguinal hernias. An indirect inguinal hernia is a congenital hernia regardless of the patient's age. It occurs because of protrusion of an abdominal viscus into an open processus vaginalis. If the processus contains viscera, it is called an indirect inguinal hernia. If peritoneal fluid fluxes between the space and the peritoneum, it is a communicating hydrocele. If fluid accumulates in the scrotum or spermatic cord without exchange of fluid with the peritoneum, it is a noncommunicating scrotal hydrocele or a hydrocele of the cord. In a girl, fluid accumulation in the processus vaginalis results in a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck. The inguinal canal forms by mesenchyme condensation around the gubernaculum, which is Latin for rudder because it guides the testis into the scrotum. During the first trimester, the gubernaculum extends from the testis to the labioscrotal fold. The processus vaginalis and its fascial coverings also form during the first trimester. A bilateral oblique defect in the abdominal wall develops during the sixth or seventh week of gestation as the muscular wall develops around the gubernaculum. The processus vaginalis protrudes from the peritoneal cavity and lies anteriorly, laterally, and medially to the gubernaculum by the eighth week of gestation. The testis produces many male hormones beginning at the eighth week of gestation. At the beginning of the seventh month, the gubernaculum begins a marked swelling influenced by a nonandrogenic hormone, probably a mullerian inhibiting substance. This results in expansion of the inguinal canal and the labioscrotal fold, forming the scrotum. The genitofemoral nerve also influences migration of the testis and gubernaculum into the scrotum under androgenic control. The female inguinal canal and processus is much less developed than the male equivalent. The inferior aspect of the gubernaculum is converted to the round ligament. The craniad part of the female gubernaculum becomes the ovarian ligament. Gonads develop on the medial aspect of the mesonephros during the fifth week of gestation. The kidney then moves cephalad, leaving the gonad to reside in the pelvis until the seventh month of gestation. During this time, it retains a ligamentous attachment to the proximal gubernaculum. The gonads then migrate along the processus vaginalis, with the ovary descending into the pelvis and the testis being enwrapped within the distal processus, known as the tunica vaginalis. The processus fails to close adequately at birth in 40-50% of boys. Therefore, other factors play a role in the development of a clinical indirect hernia. A familial tendency exists, with 11.5% of patients having a family history. The relative risk of inguinal hernia is 5.8 for brothers of male cases, 4.3 for brothers of female cases, 3.7 for sisters of male cases, and 17.8 for sisters of female cases. Pathophysiology Inguinal hernias The pinchcock action of the musculature of the internal ring during abdominal muscular straining prohibits protrusion of the intestine into a patent processus. Paralysis or injury to the muscle can disable the shutter effect. In addition, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis flattens during tensing, thus reinforcing the inguinal floor. A congenitally high position of the aponeurotic arch might preclude the buttressing effect. Neurapraxic or neurolytic sequelae of appendectomy or femoral vascular procedures may contribute to a greater incidence of hernia in these patients. Repetitive stress as a factor in hernia development is suggested by clinical presentations. Increased intraabdominal pressure is seen in a variety of disease states and seems to contribute to hernia formation in these populations. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure is associated with chronic cough, ascites, increased peritoneal fluid from biliary atresia, peritoneal dialysis or ventriculoperitoneal shunts, intraperitoneal masses or organomegaly, and obstipation. (See images below.) Other conditions with increased incidence of inguinal hernias are extrophy of bladder, neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage, myelomeningocele, and undescended testes. A high incidence (16-25%) of inguinal hernias occurs in premature infants; this incidence is inversely related to weight. The rectus sheath adjacent to groin hernias is thinner than normal. The rate of fibroblast proliferation is less than normal, while the rate of collagenolysis appears increased. Sailors who developed scurvy had an increased incidence of hernia. Aberrant collagen states, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, fetal hydantoin syndrome, Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, Hunter-Hurler syndrome, Kniest syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and Morquio syndrome, have increased rates of hernia formation, as do osteogenesis imperfecta, pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy, and Scheie syndrome. Acquired elastase deficiency also can lead to increased hernia formation. In 1981, Cannon and Read found that increased serum elastase and decreased alpha1-antitrypsin levels in people who smoke contribute to an increase in the rate of hernia in those who smoke heavily. The contribution of biochemical or metabolic factors in the creation of inguinal hernia remains speculative. Umbilical hernias Umbilical hernias in children are secondary to failure of closure of the umbilical ring, but only 1 in 10 adults with umbilical hernias reports a history of this defect as a child. The adult umbilical hernia occurs through a canal bordered anteriorly by the linea alba, posteriorly by the umbilical fascia, and laterally by the rectus sheath. Proof that umbilical hernias persist from childhood to present as problems in adults is only hinted at by an increased incidence among black Americans. Multiparity, increased abdominal pressure, and a single midline decussation are associated with umbilical hernias. Congenital hypothyroidism, fetal hydantoin syndrome, Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and disorders of collagen and polysaccharide metabolism (such as Hunter-Hurler syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), should be considered as possibilities in children with Relevant Anatomy Anterior abdominal wall The anterior abdominal wall is composed of multilaminar mirror image muscles, the associated aponeuroses, fasciae, fat, and skin. Laterally, 3 muscle layers with fascicles run obliquely in relation to each other. Each inserts into a flat white tendon, known as an aponeurosis. The paired rectus abdominis muscles originate on the pubis inferiorly and insert on the ribs superiorly. The muscle has 4 transversely oriented tendinous bands variably spaced. At the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscles is the linea semilunaris where the aponeurosis serves as an insertion for the lateral musculature. The lower edge of the posterior sheath midway between the umbilicus and the pubis with its concavity oriented toward the pubis defines the semicircular line. Above this line, anterior and posterior laminae form from division of the internal oblique aponeurosis. The posterior lamina joins the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and forms the posterior rectus sheath. The anterior rectus sheath results from fusion of the anterior lamina and the external oblique aponeurosis. The external oblique aponeurosis forms the external lamina of the anterior sheath below the semicircular line. Fusion of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis aponeuroses forms the internal lamina of the anterior sheath. The posterior surface of the rectus muscles is covered with transversalis fascia below the semicircular line. The midline linea alba represents a decussation of these fibers from the different aponeurotic layers. The external oblique muscle originates on the lower 8 ribs with obliquely and inferiorly directed fascicles inserting into its aponeurosis. Deep to the external oblique muscle is the internal oblique muscle with obliquely and superiorly oriented fascicles arising from the iliac fascia deep to the lateral half of the inguinal ligament, the anterior two thirds of the iliac crest, and from the lumbodorsal fascia. It inserts into its aponeurosis, the rectus sheath, and into the lower ribs and cartilages superiorly. The transversus abdominis muscle is most internal of the lateral abdominal wall musculature. The fascicles are generally transversely oriented. It arises from the lateral iliopubic tract, from the iliac crest, the lumbodorsal fascia, and the caudad 6 ribs. It inserts principally into its aponeurosis and fuses with the internal oblique aponeurosis to become the posterior rectus sheath. The caudad margin curves to form the transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch as the upper edge of the internal ring and above the medial floor of the inguinal canal. In 3% of cases, this arch may combine with the internal oblique aponeurosis to form the conjoined tendon. The innominate fascia overlies the external oblique muscle. The transversalis fascia forms an investing fascial envelope of the abdominal cavity. A variable layer of preperitoneal fat separates the peritoneum from the transversalis fascia. Posterolateral (lumbar) region The quadratus muscle originates from the iliac crest and the iliolumbar ligament lumborum from between iliac crest and the fifth lumbar transverse process. It then inserts along the 12th rib. The psoas muscle arises from vertebrae T-12 through L-5 and passes downward under the inguinal ligament to insert on the lesser trochanter. The serratus posterior inferior muscle originates from the lumbodorsal fascia and inserts along the 4 lowest ribs. The sacrospinalis muscle runs along the spinous processes for the entire length of the spine. The latissimus dorsi muscle originates on the posterior third of the iliac crest, the spinous processes of the sacral and lumbar vertebrae, and the lumbodorsal fascia. From this wide origin, the muscle inserts as a tendon into the intertubercular groove of the humerus. The superior lumbar triangle of Grynfeltt-Lesshaft is bounded superiorly by the 12th rib, the posterior lumbocostal ligament, and the serratus posterior inferior muscle; inferiorly by the superior border of the internal oblique muscle; and posteriorly by the lateral border of the sacrospinalis muscle. The deep margin of the superior lumbar triangle is the transversus abdominis muscle, and the superficial margin is the latissimus dorsi muscle. Spontaneous lumbar hernias occur more commonly because the potential space is larger and more constant than the inferior lumbar triangle. The inferior lumbar triangle of Petit has posterior bounds of the latissimus dorsi muscle, anterior bounds of the external oblique muscle, and inferior bounds of the iliac crest. Inguinal region Vessels regularly found during inguinal hernia repairs are the superficial circumflex iliac, superficial epigastric, and external pudendal arteries that arise from the proximal femoral artery and course superiorly. The inferior epigastric artery and vein run medially and craniad in the preperitoneal fat near the caudad margin of the internal inguinal ring. The external iliac vessels pass posterior to the inguinal ligament and iliopubic tract and anterior to the pectineal ligament to enter the femoral sheath. The external spermatic artery arises from the inferior epigastric artery just caudad to the internal inguinal ring to supply the cremaster muscle. The inguinal ligament bridges the space between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine to rotate posteriorly and then superiorly to form a shelving edge. It is the caudad edge of the external oblique aponeurosis. The ligament revolves medially to create the lacunar ligament. The lacunar ligament inserts on the pubis and courses medially and superiorly toward the midline. The external oblique aponeurosis has a triangular opening with a superior apex through which the cord enters the inguinal canal. The transversus abdominis muscle predominates as a layer of the abdominal wall for the prevention of inguinal hernias. The transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch inserts inferiorly on the Cooper ligament and contributes to the anterior rectus sheath medially. The pectineal ligament courses from the superior part of the superior pubic ramus periosteum. The components incorporate fibers from the lacunar ligament, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, and the pectineus muscle. An aponeurotic band from the caudad portion of the transversus abdominis muscle creates the iliopubic tract. It is the anterior margin of the femoral sheath and the caudad border of the internal ring. The course is from the superior pubic ramus medially to the iliopectineal arch and iliopsoas fascia, anterior to the femoral vessels, and then laterally to the anterior superior iliac spine. The iliacus fascia thickens as it exits the pelvis to form the iliopectineal arch. The fascia curves forward, lateral to the external iliac vessels, and combines with fibers from the inguinal ligament, the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, and from part of the ligament lateral attachment of the iliopubic tract. The external iliac vessels pass beneath the inguinal ligament and iliopubic tract but anterior to the pectineal ligament to enter the femoral sheath. The femoral sheath, with contributions from transversalis, pectineus, psoas, and iliacus fasciae, has 3 compartments. A femoral hernia most often occurs in the most medial compartment. The femoral canal is bounded laterally by the femoral vein. The medial margin is transversus abdominis aponeurosis insertion and transversalis fascia. The femoral canal holds lymphatic channels and lymph nodes. The superolateral border of the Hesselbach triangle is the inferior epigastric vessels. The inguinal ligament constitutes the inferolateral side. The lateral edge of the rectus sheath is the medial side. The borders of the internal inguinal ring are the transversalis fascia circumferentially and deep, the arch of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles superomedially, and the iliopubic tract inferolaterally. The course of the spermatic cord or round ligament through the abdominal wall defines the inguinal canal. Transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia combine to make the floor of the inguinal canal in 75% of persons, while a minority have only transversalis fascia. The external oblique aponeurosis is anterior, and the inguinal ligament is inferior. The vas deferens and the testicular artery and vein constitute the spermatic cord. The innominate fascia extends onto the cord as the external spermatic fascia. The cremasteric fascia and the cremaster muscle extend from internal oblique muscle and its aponeurosis to provide the most external investment of the cord. The next layer, the internal spermatic fascia is an extension of the transversalis fascia and contains the cord structures and tunica vaginalis or an indirect hernial sac when present. The inferior epigastric artery, which arises from the external iliac artery and courses with its companion vein vertically in the preperitoneal fat, is the anatomical point differentiating indirect inguinal hernias and direct inguinal hernias. Those presenting superolateral to the inferior epigastric vessels are indirect inguinal hernias, while those arising inferomedial to these vessels are direct inguinal hernias. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves originate principally from the first lumbar nerve root and have contributions from the 12th thoracic root. The nerves traverse the transversus abdominis muscle in the middle of the iliac crest, are deep to the internal oblique muscle until the anterior superior iliac spine, and then become superficial just beneath the external oblique aponeurosis. The ilioinguinal nerve then runs anterior to the spermatic cord in the canal to receive sensation from the pubis and the upper scrotum (labium majus). The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, which arises from the first and second lumbar nerve roots, becomes superficial near the internal ring to supply motor fibers of the cremaster muscle and sensation for the scrotum and medial aspect of the upper thigh. The intraperitoneal view has the medial umbilical ligament as the lateral border of the bladder, and the lateral umbilical ligament helps to identify the inferior epigastric vessels. The internal inguinal ring is the apex of a triangle formed medially by the ductus deferens and laterally by the testicular vessels. The base of the triangle contains the external iliac vessels, which may be injured during laparoscopic hernia repair. The pubic tubercle, the iliopubic tract, the transversus abdominis muscular arch, the lacunar ligament, the pectineal ligament, and the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle are usually easily visualized. The obturator internus muscle arises from the margins of the obturator foramen and the obturator membrane. The muscle fascicles exit the pelvis at the lesser sciatic foramen and have a tendinous insertion on the medial surface of the greater trochanter of the femur. The obturator vessels and nerve pass through the obturator canal, which is superior in the obturator foramen. The obturator canal runs obliquely in the medial thigh between the pectineal, external obturator, and long adductor muscles. The anterior surface of the second through fourth sacral vertebrae gives rise to the piriformis muscle to have a tendon traversing the greater sciatic foramen. Above and below this tendon, in the greater sciatic foramen, are the suprapiriform and infrapiriform foramens. The superior gluteal vessels and nerves exit through the suprapiriform foramen; the sciatic nerve, perineal nerves, and pelvic vessels pass through the infrapiriform foramen. Frequency United States 1. Over 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs are performed each year, with inguinal hernia repairs constituting nearly 770,000 of these cases.9,10,11 2. Approximately 25% of males and 2% of females have inguinal hernias in their lifetimes; this is the most common hernia in males and females.11,12 3. Approximately 75% of all hernias occur in the groin; two thirds of these hernias are indirect and one third direct.2 4. Indirect inguinal hernias are the most common hernias in both men and women; a right-sided predominance exists. 5. Incisional and ventral hernias account for 10% of all hernias.4 6. Only 3% of hernias are femoral hernias. 7. The incidence of inguinal hernias in children ranges up to 4.4%, while umbilical hernias occur in approximately 1 out of every 6 children.10,2 8. The incidence of incarcerated or strangulated hernias in pediatric patients is 10-20%; 50% of these occur in infants younger than 6 months.10 International Data from developing countries is limited, therefore, an accurate occurrence value is unavailable. Current epidemiologic assessments postulate that gender and anatomic distribution are similar. Mortality/Morbidity Morbidity is secondary to missing the diagnosis of the hernia or complications associated with management of the disease. 1. A hernia can lead to an incarcerated and often obstructed bowel. 2. The hernia also can lead to strangulated bowel with a compromised blood supply. Reduced strangulated bowel leads to persistent ischemia/necrosis with no clinical improvement. Surgical intervention is required to prevent further complications such as perforation and sepsis. 3. Ensuing surgery to repair the hernia or its complications may leave the patient at risk for infection, future hernias, or intra-abdominal adhesions. Race Umbilical hernias occur 8 times more frequently in black infants than in white infants.12 Sex 1. Approximately 90% of all inguinal hernia repairs are performed on males.11 2. Reduction of hernias in females may be complicated by inclusion of the ovary in the hernia. 3. Femoral hernias (although rare) occur almost exclusively in women because of the differences in the pelvic anatomy. 4. The female-to-male ratio of obturator hernias is 6:1. 12 Age 1. Indirect hernias usually present during the first year of life, but they may not appear until middle or old age. 2. Indirect hernias occur more frequently in premature infants compared to term infants. Indirect hernias develop in 13% of infants born before 32 weeks' gestation.10 3. Direct hernias occur in older patients as a result of relaxation of abdominal wall musculature and thinning of the fascia. 4. Umbilical hernias usually occur in infants and reach their maximal size by the first month of life. Most hernias of this type close spontaneously by the first year of life, with only a 2-10% incidence in children older than 1 year.13 Clinical History Patients with hernias present to the emergency department (ED) secondary to a complication associated with the hernia. Hernias also may be detected in the ED on routine physical examination. However, in relation to the chief complaint, the following clinical issues must be considered: 1. Asymptomatic hernia Presents as a swelling or fullness at the hernia site Aching sensation (radiates into the area of the hernia) No true pain or tenderness upon examination Enlarges with increasing intra-abdominal pressure and/or standing 2. Incarcerated hernia Painful enlargement of a previous hernia or defect Cannot be manipulated (either spontaneously or manually) through the fascial defect Nausea, vomiting, and symptoms of bowel obstruction (possible) 3. Strangulated hernia Symptoms of an incarcerated hernia present combined with a toxic appearance Systemic toxicity secondary to ischemic bowel is possible Strangulation is probable if pain and tenderness of an incarcerated hernia persist after reduction Suspect an alternative diagnosis in patients who have a substantial amount of pain without evidence of incarceration or strangulation Further anatomic considerations must be assessed in relation to the above clinical findings. The location of the underlying hernia may provide a unique constellation of symptoms with or without specific anatomic findings. 1. Femoral hernia Medial thigh pain as well as groin pain are possible because of the position of this hernia 2. Obturator hernia Because this hernia is hidden within deeper structures, it may not present as a swelling The patient may complain of abdominal pain or medial thigh pain, weight loss, or recurrent episodes of bowel or partial bowel obstruction Pressure on the obturator nerve causes pain in the medial thigh that is relieved by thigh flexion. This same pain may be exacerbated by extension or external rotation of the hip (Howship-Romberg sign) 3. Incisional hernia As these are usually asymptomatic, patients present with a bulge at the site of a previous incision Lesion may become larger upon standing or with increasing intra-abdominal pressure Physical In general, the physical examination should be performed with the patient in both the supine and standing positions, with and without the Valsalva maneuver. The examiner should attempt to identify the hernia sac as well as the fascial defect through which it is protruding. This allows proper direction of pressure for reduction of hernia contents. The examiner should also identify evidence of obstruction and strangulation. 1. When attempting to identify a hernia, look for a swelling or mass in the area of the fascial defect. Place a fingertip into the scrotal sac and advance up into the inguinal canal. If the hernia is elsewhere on the abdomen, attempt to define the borders of the fascial defect. If the hernia comes from superolateral to inferomedial and strikes the distal tip of the finger, it most likely is an indirect hernia. If the hernia strikes the pad of the finger from deep to superficial, it is more consistent with a direct hernia. 2. A bulge felt below the inguinal ligament is consistent with a femoral hernia. 3. Strangulated hernias are differentiated from incarcerated hernias by the following: Pain out of proportion to examination findings Fever or toxic appearance Pain that persists after reduction of hernia Causes Any condition that increases the pressure in the intraabdominal cavity may contribute to the formation of a hernia, including the following: 1. Marked obesity 2. Heavy lifting 3. Coughing 4. Straining with defecation or urination 5. Ascites 6. Peritoneal dialysis 7. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt 8. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 9. Family history of hernias Differential Diagnoses Epididymitis Hidradenitis Suppurativa Hydrocele Lymphogranuloma Venereum Testicular Torsion Workup Laboratory Studies 1. Complete blood count Results from CBC are nonspecific Leukocytosis with left shift may occur with strangulation 2. Electrolytes, BUN, creatinine levels Assess the hydration status of the patient with nausea and vomiting These tests are rarely needed for patients with hernia except as part of a preoperative workup 3. Urinalysis: This test assists with narrowing the differential diagnosis of genitourinary causes of groin pain in the setting of associated hernias. Imaging Studies 1. Imaging studies are not required in the normal workup of a hernia.4,6 2. Ultrasonography can be used in differentiating masses in the groin or abdominal wall or in differentiating testicular sources of swelling. 3. If an incarcerated or strangulated hernia is suspected, the following imaging studies can be performed: Upright chest radiograph to exclude free air (extremely rare) Flat and upright abdominal films to diagnose a small bowel obstruction (neither sensitive or specific) or to identify areas of bowel outside the abdominal cavity 4. CT scanning or ultrasonography may be necessary in the following cases: To diagnose a spigelian or obturator hernia Inability to obtain a good examination because of body habitus Treatment Emergency Department Care Reduction of a hernia 1. Provide adequate sedation and analgesia to prevent straining or pain. The patient should be relaxed enough to not increase intra-abdominal pressure or to tighten the involved musculature. 2. Place the patient supine with a pillow under his or her knees. 3. Place the patient in a Trendelenburg position of approximately 15-20° for inguinal hernias. 4. Apply a padded cold pack to the area to reduce swelling and blood flow while establishing appropriate analgesia. 5. Place the ipsilateral leg in an externally rotated and flexed position resembling a unilateral frog leg position. 6. Place 2 fingers at the edge of the hernial ring to prevent the hernial sac from riding over the ring during reduction attempts. 7. Firm, steady pressure should be applied to the side of the hernia contents close to the hernia opening, guiding it back through the defect. 8. Applying pressure at the apex, or first point, that is felt may cause the herniated bowel to "mushroom" out over the hernia opening instead of advancing through it. 9. Consult with a surgeon if reduction is unsuccessful after 1 or 2 attempts; do not use repeated forceful attempts. 10. The spontaneous reduction technique requires adequate sedation/analgesia, Trendelenburg positioning, and padded cold packs applied to the hernia for a duration of 20-30 minutes. This can be attempted prior to manual reduction attempts. Treatment Medical Therapy Trusses place pressure on the skin and bowel, induce related injury, and mask signs of incarceration and strangulation. The temporary use of binders or corsets can be useful in patients with large-necked hernias, during the preoperative period, or with a high risk of operation on a long-term basis. Reduction Sedation, analgesia, and Trendelenburg positioning may aid in the reduction of an incarcerated hernia. Ice cooling of an incarcerated hernia is counterproductive. Simple pressure over the distal sac usually is ineffective since the incarcerated viscera then mushroom over the external ring. Pressure directed medially at the external ring and maintained for several minutes, while simultaneously invaginating the distal sac, will often reduce a difficult incarcerated viscus. Hernia content balloons over the external ring when reduction is attempted. Hernia can be reduced by medial pressure applied first. In children, pressure should be applied from the posterior and directed laterally and superiorly through the external ring. Of note, the internal ring in infants is more medial than in older children and adults. The hourglass configuration of a hernia/hydrocele complex will not reduce with pressure applied to the hydrocele portion. Topical therapy Cauterization with silver nitrate aids in the resolution of an umbilical granuloma. If there is a stalk, ligation of the base resolves the problem. Delaying the repair of umbilical or asymptomatic epigastric hernias until children are older than 5 years allows spontaneous closure in most children. Strapping, with or without a coin, is not indicated in the treatment of umbilical hernia because of problems with skin erosion and lack of effectiveness. Grob introduced the use of Mercurochrome as an escharotic for scarifying the intact sac of a giant omphalocele. However, the development of mercury poisoning terminated its use. Chemical dressings using silver sulfadiazine (complication is leukopenia), povidone-iodine solution (complication is hypothyroidism), 0.5% silver nitrate solution (complication is argyrism), and gentian violet have served as agents to protect against infection while the sac epithelializes. In current practice, only life-threatening associated conditions, poor probability of survival in infants, or failure of better means of coverage warrant use of these methods. A large residual ventral hernia results, which may be problematic because of loss of domain. Progressive compression dressing of an omphalocele sac with an inner layer of saline moistened dressings and an outer dressing of Coban can reduce viscera over 5-10 days, after which delayed primary fascial and skin closure is accomplished. For children with an omphalocele and life-threatening associated conditions, a poor probability of survival, or a very large omphalocele, the combination of topical escharotic agents and daily abdominal wrapping with an ACE bandage has produced successful closure in many patients. As the child grows, the defect remains the same size and becomes smaller relative to the increasing abdominal wall. Delayed closure following epithelialization can allow primary fascial closure with no prosthesis, which eliminates the need for multiple operations. External coverage with pigskin, skinlike polymer membrane, or human amniotic membrane can be used adjunctively in the treatment of giant omphalocele or after failed primary therapy. Surgical Therapy Inguinal hernia Treatment for adult inguinal hernia is described as follows: After a diagnosis is established, the signs, symptoms, and risks of incarceration, as well as the timing, conduct, and risk of the repair procedure, should be explained to the patient or to the parents of the child. Most repairs proceed within several weeks and are dependent on multiple factors (eg, employment, insurance). Massive hernias need prosthetic material to aid closure in most patients, and appropriate materials should be available in the operating room prior to incision. Progressive pneumoperitoneum, using increasing volumes of air over time, may allow accommodation to increased intraabdominal pressure but probably does little to increase the size of the abdominal cavity. Adults with very large chronic hernias should be admitted postoperatively because of the combination of ileus from extensive manipulation and the loss of domain with the attendant problems of increased pressure on the diaphragm, vena cava, kidneys, and hernia closure. The adult who presents with bilateral hernias without the need for formal reconstruction can have simultaneous repair, whereas more complex procedures should be metachronous by a month or more. Local anesthesia is sufficient for most repairs in adults; however, prolonged procedures, repair of hernias with a large intraperitoneal component, including laparoscopy, and repair of recurrent hernias are best managed with spinal, epidural, or general anesthesia. The use of routine preoperative antibiotics in low-risk adults undergoing a standard tension-free repair with mesh is not currently recommended, as multiple studies have shown no benefit in decreasing postoperative wound infection. Pediatric surgeons repair soon after diagnosis, regardless of age or weight, in healthy full-term infant boys with asymptomatic reducible inguinal hernias.11 In full-term girls with a reducible ovary, most surgeons operate at a close elective date, but, if the ovary is not reducible but asymptomatic, more urgent timing of surgery is preferred. Premature infants with inguinal hernias are usually repaired prior to discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), but this practice is changing, as infants are now being discharged home at much lower weights. Some surgeons prefer to postpone the surgery in these very small babies for 1-2 months to allow further growth. Apnea is common in postoperative infants. These young infants should have an apnea monitor during the postoperative period.12,13,14 All children with bilateral presentation should undergo bilateral inguinal hernia repair under a single anesthesia. However, potential damage to the spermatic cord structures in boys argues against routine contralateral exploration. Controversy exists over the routine exploration of the opposite side in children with unilateral inguinal hernias.15 Previous practices of routinely exploring the opposite side in all boys younger than 2 years and all girls younger than 4-5 years are no longer popular. Most surgeons do not routinely perform open exploration of the contralateral groin, except in cases of high anesthetic risk (eg, congenital heart disease, premature infants), risk for developing contralateral hernia secondary to increased intraabdominal pressure (eg, peritoneal dialysis, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, ascites), or limited access of the child to appropriate medical care should an incarceration occur on the opposite side. Current practice in many pediatric centers uses peritoneoscopy through the ipsilateral inguinal sac to identify contralateral patent processes and hernias. Long-term follow-up is needed because only 20% of the patent processes identified become clinically apparent hernias in the short term. A surgeon who is unfamiliar with the tissue characteristics and metabolic and psychological needs of children or who does not have a skilled pediatric anesthesiologist available should not attempt a hernia operation in a young child. Older children usually have general inhalation anesthesia, whereas some anesthesia providers use spinal or continuous caudal anesthesia with preterm infants. Preemptive regional anesthesia, by ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve block or by caudal block, decreases postoperative discomfort. The routine use of perioperative antibiotics for uncomplicated inguinal hernia repairs in children is not generally indicated. Some cardiologists advise prophylactic antibiotic use to lower the risk of endocarditis in children with associated cardiac defects; patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts may also benefit. Postoperative apnea is common in premature 16 infants. Premature infants younger than 50 weeks’ gestational age should be admitted for 24 hours postoperatively and placed on a cardiorespiratory monitor. Patients undergoing a neurectomy have a significantly lower prevalence of neuralgia without increased paresthesia. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated in low-risk adult patients undergoing open mesh inguinal repair. Preoperative Details A full preoperative assessment and adequate fluid resuscitation precede early operation. The fluid requirements for an infant with gastroschisis are 2-8 times the usual requirements for the first 24 hours of life because of the visceral inflammation. Maintenance of urinary output of 1-2 cm3/kg/h by closely monitored administration of crystalloids keeps the infant properly hydrated. A sump type nasogastric tube should be passed through the mouth and into the stomach and placed on suction to negate the effects of the ileus. Intraoperative Details Surgical options depend on type and location of hernia. The fundamentals of indirect inguinal hernia repair are basically the same regardless of the age at presentation. Reduction or excision of the sac and closure of the defect with minimal tension are the essential steps in any hernia repair. If tissue is sufficiently attenuated as to preclude following these precepts, many techniques involving the release of tension by flaps, prosthetic materials, or a simple relaxing incision in adjacent tissue will fulfill the requirements. Overlay, underlay, and sandwiching of the edges with plastic meshes constitute most techniques today. Return to work is dictated by the approach and the amount of physical activity involved with the job. Accurate postoperative instruction and easy access to care (if problems arise) are as effective as a full postoperative visit following routine inguinal hernia repairs. Basic repair techniques - The Bassini repair The essence of the Bassini repair is apposition of the transversus abdominis, transversalis fascia, and lateral rectus sheath to the inguinal ligament. This is usually performed by imbrication. The Shouldice technique uses 2 layers of running suture in a similar fashion. Bassini-type repair approximating transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia to iliopubic tract and inguinal ligament. Basic repair techniques - The Cooper repair The greatest proponent of the Cooper repair is McVay. This repair approximates the conjoint area, transversus abdominis, and transversalis fascia to the pectineal ligament. Overlying the vein, these structures are sewn to the iliopubic tract. It also provides a good approach for the repair of femoral hernias. The standard adult hernia repair now uses prostheses to reinforce the floor, usually polypropylene mesh. The material can overlay, underlay, or sandwich the area or be used as a plug. This provides a tension-free repair and excellent results, but it carries a slightly increased risk of wound infection. The preperitoneal approach has advocates who claim ease in identifying the sac, reducing the contents, and dissecting the cord structures. Mechanical advantages include the use of natural intra-abdominal pressure to keep the mesh in place over all potential hernia sites. The best uses are in the incidental repair of a hernia during other abdominal procedures, recurrent hernias, and femoral hernias. A Pfannenstiel, lower midline, or other incision is used to reach the preperitoneal plane. The internal inguinal ring and the hernia sac are identified lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. After dissecting the sac from the testicular vessels and vas deferens, it is divided and the peritoneum is closed. The repair follows the pectineal approach and often has mesh applied. The laparoscopic approach is being increasingly used for both primary hernias and recurrent hernias. The endoscopic totally extraperitoneal approach (TEP) is usually favored over the transabdominal preperitoneal operation (TAPP) because of the complications that arise from exposed intraperitoneal mesh in the TAPP repair. Postoperative pain, time to full recovery, and return to work are improved with the laparoscopic approach, but it is more expensive. Short-term recurrence data are similar, but there has been insufficient length of follow-up to completely compare it to the more conventional approaches. Complications Iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal neuralgia usually will regress within months. Nerve blocks or neurectomy can be used in refractory cases. Most recurrences happen within 5 years of operation and are often associated with incarcerated hernias, concurrent orchidopexy, sliding hernias in girls, and emergency operations. The recurrence rate is higher in children younger than 1 year and in the elderly. Recurrence is more common in patients with ongoing increased intra-abdominal pressure, growth failure and malnutrition, prematurity, seizure disorder, and chronic respiratory problems. Technical factors increasing recurrence include an unrecognized tear in the sac, failure to repair a large internal inguinal ring, damage to the floor of the inguinal canal, and infection or other postoperative complications. A direct hernia sometimes results from vigorous dissection or may have been a simultaneous hernia unrecognized initially. Other hernias Recurrence, bleeding, infection, and persisting pain are potential complications for the other abdominal wall hernias. Incisional hernias may have a 30% rate of recurrence. The addition of mesh to most abdominal wall hernia repairs is decreasing the incidence of recurrence. Outcome and Prognosis Inguinal hernias Hernia recurrence, infarcted testis or ovary with subsequent atrophy, wound infection, bladder injury, iatrogenic orchiectomy or vasectomy, and intestinal injury are complications of hernia repair. (See image below.) Postoperative death is usually related to complications, such as strangulated bowel, or to preexisting risk factors. 20 A postoperative hydrocele results from fluid accumulation in the distal sac. This usually resolves spontaneously but sometimes requires aspiration. A femoral hernia as a sequela of inguinal hernia repair may have been primarily overlooked. Unilateral transection of the vas deferens can cause infertility through antibody production. Iatrogenic cryptorchidism can occur in children (1.3%) if the testicle is not placed in the scrotum at the end of the operation and requires orchiopexy for correction. For strangulated hernias, start broad-spectrum antibiotics. Antibiotics are administered routinely if ischemic bowel is suspected. Antibiotics These agents are to be used if the patient has a strangulated hernia. Uncomplicated inguinal and abdominal wall hernias do well. However, hernias with associated strangulation have an associated mortality rate of 10%. Infants with uncomplicated gastroschisis and omphalocele fare well with a mortality rate of less than 5%;22however, those with intestinal atresia or severe associated anomalies have a mortality rate of 15-50%. Consultations Consult a surgeon for the following reasons: 1,16,3 1. Inability to reduce the hernia 2. Concern for a strangulated bowel and a patient with a toxic appearance 3. Patients with comorbid risks for sedation should have a surgeon present for the initial reduction attempt Medication Cefoxitin (Mefoxin) Multiple regimens that cover for bowel perforation and/or ischemic bowel can be used. Cover for both aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacteria. Adult 1-2 g IV q8h Pediatric 80 mg/kg/d IV divided into 4 equal doses q6h Follow-up Further Inpatient Care All incarcerated or strangulated hernias demand admission and immediate surgical evaluation. Further Outpatient Care 1. Follow-up visits with the general surgeon should be scheduled within the next 1-2 weeks for those patients with easily reducible hernias or with hernias found upon physical examination. 2. Discharge patients with umbilical hernias with close follow-up care if the defect is less than 2 cm in diameter and the hernia is not incarcerated or strangulated. 3. Educate patients to avoid those activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure. 4. Educate patients to return for inability to reduce hernia, increased pain, fever, and vomiting. Deterrence/Prevention Counsel the patient on avoidance of activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as straining at defecation or lifting heavy objects. This may require work or school-related activity restrictions and should be clearly delineated. Complications 1. If strangulation of the hernia is missed, bowel perforation and peritonitis can occur. 2. Hernias can reappear in the same location, even after surgical repair. Prognosis 1. The prognosis depends on the type and size of hernia as well as on the ability to reduce risk factors associated with the development of hernias. 2. The prognosis is good with timely diagnosis and repair. Patient Education 1. Counsel the patient to avoid those activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as straining at defecation and lifting heavy objects. 2. Instruct the patient to apply support to the hernia. Numerous medical device companies have developed support items to assist with this process. 3. Even with asymptomatic hernias, early repair (ie, before it enlarges) is preferred. Referral to a general surgeon for discussion about type of repair is warranted as a wide variety of hernia repair options now exist with advent of new meshes and laparoscopy. Miscellaneous Medicolegal Pitfalls 1. Failure to consider the diagnosis of hernia in patients who present with nausea and/or vomiting 2. Diagnosing testicular torsion as a hernia without appropriate evaluation or imaging considerations (puts the testicle at risk) 3. Reducing a strangulated bowel without recognizing it (The hernia will be reduced, but the bowel will remain ischemic.) 4. Failure to provide adequate instructions for patients with reduced hernias regarding follow-up and the need to return to the ED for worsening or persistent recurrent symptoms Special Concerns Pain after reduction of a hernia may indicate a strangulated hernia, requiring further evaluation by a surgeon.