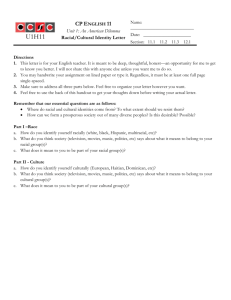

Identifying and Understanding Perceived Inequities in Local Political

advertisement