Ralph Waldo Emerson

advertisement

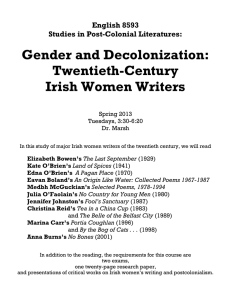

Forging the National Economy, 1790-1860 The progress of invention is really a threat (to monarchy). Whenever I see a railroad I look for a republic. Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1866 The Westward Movement • Andrew Jackson was the first president from beyond the Appalachian Mountains. He exemplified the westward march of the American people. “The West, with its raw frontier, was the most typically American part of America.” • Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in 1844, “Europe stretches to the Alleghenies; America lies beyond.” • By 1850, half of Americans were under the age of thirty. They were young and energetic. • By 1840, the “demographic center” of the American population had crossed the Alleghenies. By the start of the Civil War, it had marched across the Ohio River. Even so, life was very hard on the frontier. • Ralph Waldo Emerson’s popular lecture-essay “Self-Reliance” portrayed life in the frontier. Writers such as Herman Melville’s restless Captain Ahab and James Fennimore Cooper’s heroic Natty Bumppo became popular American literature. • Pioneers learned to rely upon each other. Shaping the Western Landscape • The westward movement also affected the physical environment. Pioneers often exhausted the land in the tobacco regions. In Kentucky, cane as high as fifteen feet posed an insurmountable barrier until settlers discovered that when the cane was burned off, European bluegrass thrived. Erroneously, it has been called Kentucky bluegrass. This was ideal for livestock. • By the 1820’s, fur trappers were roaming the Rocky Mountain region. Fur-trapping relied upon the “rendezvous” system. Each summer, traders from St. Louis ventured to a Rocky Mountain valley, made camp, and waited for the trappers and Indians to arrive with beaver pelts to swap for manufactured goods from the East. Unfortunately, the beaver almost disappeared from the region. Buffalo almost came to a virtual annihilation due to the buffalo hides. On the California coast, sea-otter pelts brought in a high price. Again, the otter almost came near extinction. • Some historians have called this exploitation of the West’s natural bounty “ecological imperialism.” • Yet Americans during this period reverenced nature and admired its incredible beauty. This attitude toward the beauty of the American wilderness sparked and inspired literature and painting, and eventually led to a conservation movement. • George Catlin, a painter and student of Native American life proposed the creation of a national park. His idea later led to the creation of a national park system beginning with Yellowstone Park in 1872. The March of the Millions • As the American people moved west, they multiplied at an amazing rate. By mid-century the population was doubling approximately every 25 years. • By the Civil War, the United States was the fourth most populous nation in the western world, exceeded only by three European countries-Russia, France, and Austria. • Urban growth also exploded. By 1860 there were forty-three cities of populations of 20,000 or more. • Over rapid urbanization brought undesirable by-products. Smelly slums, bad street lighting, inadequate policing, impure water, foul sewage, rats, and improper garbage disposal. • A continuing high birthrate accounted for most of the increase in population, but by the 1840’s the tides of immigration were adding hundreds of thousands more. • During the 1840’s-1850’s, over a million and a half Irish and Germans came to America. • Why did they come: – Europe was running out of room – Freedom from the aristocratic class – Freedom from a state church – Abundant opportunity to own land and better one’s condition. – Transoceanic steamships could bring immigrants at a much faster rate (10-12 days compared to 10 -12 weeks. The Emerald Isle Moves West • Ireland, already groaning under the heavy handed of British overlords, experienced additional problems. • In the mid-1840’s a severe potato famine it Ireland. All told, about 2 million Irish perished. • Tens of thousands of Irish flocked to America in the “Black Forties.” • Too poor to move west and buy land, livestock, and equipmentswarmed into the larger seaboard cities. Many came to Boston and New York which became the largest Irish city in the world. • The Irish were forced to live in rudely crammed slums. They were scorned by the older American stock, especially “proper” Protestant Bostonians, who regarded the Catholic arrivals as a social menace. • “Biddies” (Bridgets) took jobs as kitchen maids and “Paddies” (Patricks) were pushed into pickand-shovel jobs on canals and railroads. As jobs were hard to come by, they were hated by the workers. “No Irish Need Apply” (NINA). The Irish, as a result fiercely resented the blacks, who also challenged them for the low paying jobs. • Race riots between black and Irish dockworkers flared up in several port cities. • The Ancient Order of Hibernians, a semisecret society founded in Ireland to fight the landlords, served in America as a benevolent society, aiding the downtrodden. The society also created the “Molly Maguires,” a shadowy Irish miners’ union that rocked the Pennsylvania coal districts in the 1860’1870’s. • Politics attracted the Irish. Soon, they began to gain control of powerful city machines (political parties that ran cities). The most infamous (known for something bad) Irish organization was New York’s Tammany Hall, a corrupt Democratic organization that ran New York City. Before long, Irish dominated police departments in many big cities, where they drove the “Paddy wagons” that had once carted their forebears to jail. • Because of the Irish population, politicians tried to get the Irish vote, especially in the state of New York. • Nearly 2 million Irish arrived between 1830 and 1860. The Irish greatly resented Britain. The German Forty-Eighters • The incoming of refugees from Germany between 1830 and 1860 was equal to that of Ireland. Over a million and a half Germans came to America during this time. • Most of the Germans had been farmers. Due to the collapse of the democratic revolutions of 1848, the Germans decided to leave the autocratic fatherland and flee to America-the brightest hope for democracy. • Germans, such as patriotic Carl Schurz made a tremendous impact on American life. Schurz was a relentless foe of slavery and public corruption. • Many of the German newcomers, unlike the Irish, possessed a modest amount of material goods. Because of this, most of them pushed out to the Middle West, notably Wisconsin. Here, they settled and established model farms. Like the Irish, they formed an influential body of voters whom American politicians went after. The Germans were less politically powerful since they were more widely scattered than the Irish. • The Germans contributed much to the American culture: – The Conestoga wagon, the Kentucky rifle, and the Christmas tree were German contributions to the American culture. – The Germans also promoted the idea of American isolationism in the upper Mississippi Valley. Since they had fled from an autocratic European society, they had no desire to entangle themselves again with Britain. – Being better educated than many of the pioneers, the Germans supported their Kindergarten (children’s garden). • As outspoken champions of freedom, the Germans became relentless enemies of slavery during the years before the Civil War. • Seeking to preserve their language and culture, they sometimes settled in compact “colonies” and kept to themselves. • The Germans drank huge quantities of bier (beer). Their Old World drinking habits caused the advocates of temperance to double their efforts against drinking. Flare-Ups of Antiforeignism • The influx of the German and Irish immigration inflamed the prejudices of American “nativists.” They were afraid that these foreigners would outbreed, outvote, and overwhelm the existing population. • Not only did the newcomers take jobs from “native” Americans, but a large majority of the Irish were Roman Catholic, as were a substantial minority of the Germans. • Roman Catholicism spread throughout America. The religious fervor caused the Irish to form their own Catholic Schools “Parochial Schools” (religious school). By 1850, the Catholics were the largest religious group. • American nativists rallied for political action. In 1849, they formed the Order of the StarSpangled Banner, which eventually formed in the American or “Know-Nothing” Party. • Nativists wanted strict immigration and naturalization restrictions and laws authorizing the deportation of alien paupers (poor). • The Nativists used literature, mainly pure fiction, to belittle the Catholics. One such book was: Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosures (1836) which sold over 300,000. Though fiction, the book depicted a runaway nun who had escaped from a Catholic convent. After escaping, Maria Monk disclosed the abuse that she had suffered while at the convent. • Attacks mounted against Catholic schools and churches. The most frightful occurred during 1844 in Philadelphia, where the Irish Catholics fought back against the threats of the “nativists.” Two Catholic churches had been burned and some thirteen citizens and been killed and fifty wounded during the several days of fighting. • Immigrants were making America a more pluralistic society (many cultures). America was one of the most ethnically and racially varied in the history of the world. It was no wonder that cultural clashes would occur. • The reason why more riots did not occur was due to the robustness of the American economy. Once the immigrants arrived, they could claim their share of American wealth without jeopardizing the wealth of others. Most of the isolated riots occurred in the congested cities of America. The immigrants hands and brains helped fuel the American economy. • Immigrants and the American economy needed each other. Without the newcomers an agricultural united States might well have been condemned to watch as the Industrial Revolution swept through nineteenth-century Europe. The March of Mechanization • Samuel Slater has been acclaimed the “Father of the Factory System.” Slater was a skilled British mechanic of 21. He came to America in disguise after memorizing the plans for the machinery. In 1791, Slater put into operation the first efficient American machinery for spinning cotton thread. • Eli Whitney, from Massachusetts, invented the cotton gin (gin-short for engine)-1798 which separated the cotton fibers from the seeds. The cotton gin revolutionized the cotton industry of America as well as the whole world. • The South was now tied to King Cotton. Slavery had been dying out but was revitalized by this new invention. Slave-driving planters were not moving from the depleted tidewater plains over into Alabama and Mississippi. • The Industrial Revolution was now on the march in America. • New England now thrived as an industrial center: – Stony soil discouraged farming – Dense population provided labor – Shipping brought in capital (materials with which to manufacture) – Seaports- importing raw materials and exporting finished products – Rapid rivers provided abundant water power. By 1860, there were over 1,000 cotton mills, mostly in New England. Marvels in Manufacturing • American factories spread slowly until about 1807, when there began the embargo Act, nonintercourse Act, and the War of 1812. • Manufacturing halted after the treaty of Ghent in 1815. British manufactures dumped low priced products onto the American market. Many mills were forced to close. The Tariff of 1816 brought some relief. • Manufacturing of firearms greatly increased after Eli Whitney, again, began producing muskets with interchangeable parts. This would be done by machine rather than by hand. • The principle of interchangeable parts was widely adopted by 1850, which ultimately became the basis of modern mass-production, assembly-line methods. • Eli Whitney contributed much to the North winning the Civil War. • Elias Howe in 1846 and perfected by Isaac Singer, gave another strong boost to northern industrialization. • The sewing machine became the foundation of the ready-made clothing industry, which took hold about the time of the Civil War. It drove many seamstresses from the home to the factory. • 306 patents in 1800 grew to 28,000 by 1860. • The principle of limited liability aided the growth of business in allowing the individual investor, in cases of legal claims or bankruptcy, to risk no more than his own share of the corporation’s stock. These were called investment capital companies. • Laws of “free incorporation,” first passed in New York in 1848, which meant that businessmen could create corporations without applying for individual charters from the legislature. • Samuel F.B. Morse’s telegraph was among the inventions that tightened the links of an increasingly complex business world. His first typed message over 40 miles of wires said, “What hath God wrought?”. Instantly separated people were joined together. Workers and “Wage Slaves” • Prior to the factory system most work was done in the home. Both owner and apprentice worked together. The factory system isolated the owner and worker. Working conditions were very harsh and little contact was made between the worker and owners. • Workers were forbidden by law to form labor unions since it was considered criminal conspiracy. Only 24 recorded strikes were recorded before 1835. • Child workers were especially vulnerable to exploitation. In 1820, one half of the nation’s industrial workers were children under ten years of age. “Whipping” rooms were used to brutally whip children. Many children were mentally, emotionally, and physically scarred. • In contrast, the situation of most adult workers improved in the 1820’s and 1830’s. Many states granted the laboring man the right to vote. • Many workers gave their loyalty to the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson, whose attack on the Bank of the United States and against all forms of “privilege” reflected their anxieties about the emerging capitalist economy (economy whereby businesses are privately owned. • The ten-hour workday, higher wages, better working conditions, public education for the children, and an end to imprisonment for debt heightened the Jacksonian era. • Workers learned the value of the strike even if it was against the law. Dozens of strikes erupted in the 1830’s and 1840’s. Employers would hire “scabs” or “rats” (those hired to replace strikers). Immigrant workers would fill the jobs. • By 1830, there were 300,000 trade unions. However, the depression of 1837 ended union membership as unemployment grew. • In 1842, the supreme court of Massachusetts ruled in the case of Commonwealth v. Hunt that labor unions were not illegal conspiracies, provided that their methods were “honorable and peaceful.” • Unions still had about a century before they could meet management on relatively even terms. Women and the Economy • Working conditions were very difficult for women. They worked six days a week for twelve or thirteen hours- “from dark to dark.” • Boston factories pridefully pointed to their textile mill at Lowell, Massachusetts (The Lowell System). The workers were all New England farm girls, carefully supervised on and off the job. They were escorted regularly to church from their company boardinghouses, forbidden to form unions, they were as disciplined and docile a labor force as any employer could wish. • Opportunities for women to be economically self-supporting were scarce. Nursing, domestic service, and teaching were the primary jobs for women. • Catherine Beecher, sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe and daughter of a famous preacher, encouraged women to enter the teaching profession. • About 10% of white women were working for pay outside their homes by 1850. • Most working women were single. After marriage they left their jobs and took their jobs at home. At home, they were enshrined in a “cult of domesticity,” a widespread cultural creed that glorified the customary functions of the homemaker. From their pedestal, married women commanded immense moral power, and they increasingly made decisions that altered the character of the family itself. • The changing roles of women and the spreading industrial revolution brought some important changes in the life of the nineteenth-century home-the traditional “women’s sphere.” • Love, not parental “arrangement,” more frequently determined the choice of a spouse. Families thus became more closely knit and affectionate, providing the emotional refuge from the big-city tolerable. • Families grew smaller often by the woman’s choice. This new role for women has been called “domestic feminism.” It signified the growing power and independence of women, even while they remained wrapped in the “cult of domesticity.” • Families became more child-centered. Europeans saw American families as being too permissive. The reality was an emerging new idea of child rearing, in which the child’s will was not to be simply broken, but rather shaped. • In the little republic of the family, as in the Republic at large, good citizens were raised not to be meekly obedient to authority, but to be independent individuals who could make their own decisions based on internalized moral standards. • The “modern family” was: small, affectionate, child-centered, and provided a special arena for the talents of women. • To many feminists later, this role would look stifling but to many women of the time it was a big step from the conditions of grinding, often alongside men in the fields, in which their mothers had lived. Western Farmers Reap a Revolution in the Fields • As factories altered the East, flourishing farms were changing the face of the West. The transAllegheny region, especially the Ohio-Indiana-Illinois areas was fast becoming the nation’s and the world’s breadbasket. • Corn was processed into grain and liquor. They became the farmer’s staple market items. So many hogs were butchered, traded, or shipped that Cincinnati came to be know as the “Porkopolis” of the West. • West produce was at first floated down the Ohio-Mississippi River to the booming Cotton Kingdom. • John Deere of Illinois in 1837 produced a steel plow that broke the hard matted soil. In the 1830’s Cyrus McCormick of Virginia invented the mechanical mower-reaper. The reaper was to the western farmer what the cotton gin was to the southern planters. The reaper allowed the small farmer to become wealthy capitalists. • Subsistence farming (farming enough to live on) gave way to production for the market (sold to the public). Largescale (“extensive”), specialized, cashcrop agriculture came to dominate the trans-Allegheny West. Farmers wanted more land and more machinery which in turn increased debt. • The industrial farmer needed expanded markets in which to sell their products. Farm products traveled North and South along the Ohio and Mississippi. A transportation revolution would be necessary. Highways and Byways • In the 1790’s the Lancaster turnpike in Pennsylvania was made. It was a 62 mile hardsurfaced highway that went from Philadelphia to Lancaster. As drivers approached the toll gate, they had to pass a barrier of sharp pike. After a toll was paid, the barrier was turned aside to let the driver through-thus, the term turnpike. Proving to be so successful, turnpikes were built throughout the west stimulating trade. • States’ righters objected to federal money being given to the states. They were fearful that the national government could control the states. Easterners also resented the federal money since the new roads reduced their populations. • The National Road, or Cumberland Road connected western Maryland to Illinois a distance of 591 miles. This road with numerous branches was a major stimulus to American prosperity. Immigrants, freight and commerce flooded to the west. The age of rapid land transportation was now dawning. Fulton Reverses the Rivers • The steam boat revolution overlapped the turnpike revolution in transportation. • Robert Fulton became the first engineer to build a successful seam engine that could navigate a boat up river. His first boat, the Clermont successful ran up the Hudson River toward Albany, New York a distance of 150 miles in 32 hours. • Trade by river doubled since trade could now go both up and down rivers. • By 1860, 1000 steamboats sailed up and down the Mississippi. • Steamboats played a major role in opening up the West and South and populating cities along the rivers. “Clinton’s Big Ditch” in New York • New Yorker’s were not given federal aid for the Erie Canal, linking the Great Lakes with the Hudson River. As a result, they built the canal themselves. Governor DeWitt Clinton’s project was, at first, called “Clinton’s Big Ditch” or “the Governor’s Gutter.” • The canal proved to be an explosive economic success. The cost of shipping a ton of grain from Buffalo to New York City fell from $100 to $5 and the time of transit went from twenty days to six days. • Land skyrocketed along the sides of the canal. New Cities grew and blossomed along the canal banks. • Industry grew • Farming attracted many settlers and immigrants in Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois. • Cities such as Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago exploded into might cities. • Industrialization grew as a result of canal building. • Long-established local market economies were now being swamped by a huge continental economy. Instead of selling to a small area, products could be shipped and sold all over the nation and world. Pioneer Railroad Promoters • The railroad proved to be the most significant contribution to the development of a continental economy. • The railroad was fast, reliable, cheaper than canals to construct, and not frozen over in winter. It could go almost anywhere. • The railroad was first introduced in the United States in 1828. by 1860 (32 years later) the United States had 30,000 miles of railroad track, three-fourths of it was in the rapidly industrializing North. • At first, canal investors resented the competition of the railroad. • The railroad bound America together with iron and later steel. • The Pullman car (“sleeping palace”) was introduced in 1859. The Transport Web Binds the Union • The desire of the East to tap the West stimulated the “transportation revolution.” • Until about 1830, the “natural” flow of trade was southbound down the Mississippi river. With the steamboat, transportation could flow up river. The West and South were connected by North/South waterways. • The truly revolutionary changes in commerce and communication came during the 30 years before the Civil War as canals and railroad tracks radiated out from the East to West and vice-versa. • The Mississippi and New Orleans was increasingly robbed of its traffic, as goods moved eastward and westward on trains and canal boats. • New York City became the Seaboard queen of the nation. • As did the division of labor apply to the factory (each person doing a particular job) so was the nation regionalized (sectionalized) to a particular type of economic activity: – The South raised cotton for export to New England and Old England – The West grew grain and livestock to feed factory workers in the East and in Europe – The East made machines and textiles for the South and the West. • Many southerners regarded the Mississippi as a silver chain that naturally linked the upper valley states to the Cotton Kingdom. They were convinced, as secession approached, that some or all of these states would have to secede with them or be economically cut off. • However, this proved not to be the case since the upper Mississippi states proved to be tightly linked economically to the East. • Social Effects: The emergence of a specialized, continentalscale economy had far-reaching social effects. – As more and more Americans were linked to the national economy, the self-sufficient households of the colonial days were transformed. Most families had once raised all their own food, spun their own wool, and bartered with their neighbors for necessities. Now, they scattered to work for wages in the mills, or they planted just a few crops for sale at market and used the money to buy goods made by strangers in far-off factories. • “A quiet revolution occurred in the household division of labor and status.” Traditional women’s work was rendered superfluous and devalued as store-bought fabrics, candles, and soap replaced homemade products. The home, once a center of economic production in which all family members cooperated, grew into a place of refuge from the world of work, a refuge that became increasingly the special and separate sphere of women. Wealth and Poverty • Revolutionary advances in manufacturing and transportation brought increased prosperity to all Americans, but these advances also widened the gulf between the rich and the poor. By the Civil War, a new class of “millionaires” was forming. • “Cities bred the greatest extremes of economic inequality.” The Unskilled workers always fared worst. Many of these were “drifters” or wanderers who, at times, made up half the population of the industrial centers. • “Social Mobility” did occur but not at the rate imagined. “Rags-toriches” success stories were relatively few. • The American standard of living was still higher than those countries of Europe. Cables, Clippers, and Pony riders • A new pattern of American foreign trade emerged in the antebellum (before the Civil War) years. Cotton accounted for more than half the value of all American exports. • “After the repeal of the British exclusionary Corn Laws in 1846, the wheat gathered by McCormick’s reapers began to play an increasingly important role in trade with Great Britain.” • Americans tended to export agricultural products and imported manufactured goods. They tended to import more than they exported, running up substantial debts to foreign creditors. • In 1858 Cyrus Field stretched a cable under the deep North Atlantic waters from Newfoundland to Ireland. America and Europe was now connected. • American shipping rose to prominence with the Savannah, a steamer that sailed across the Atlantic in 1819. • By the 1840’s and 1850’s, a golden age dawned for American shipping. Clipper Ships were being build that sailed at very fast speeds. The ships sacrificed cargo for speed. The ships took the tea trade between the Far East and England from the slow British sailing ships. They were used to sail adventures to the gold fields of California and Australia. • The British won out on the eve of the Civil War with their “steamers” (“teakettles”). • By 1858 stagecoaches, immortalized by Mark Twain’s Roughing It, were riding the west from the Missouri River to California. • 1860 saw the Pony Express in 1860 to carry mail 2,000 from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacrament, California in 10 days. It lasted only 18 months. Morse’s telegraph led to the doom of the Pony Express by 1861. • “The swift ships and the fleet ponies ushered out a dying technology of wind and muscle. In the future, machines would be in the saddle.”