RevisedPaperGreatChainofBeing

advertisement

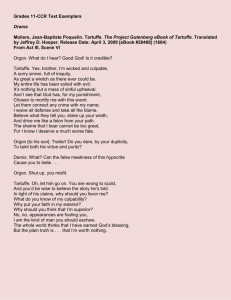

Paper 1: The Great Chain of Being (Pope x Molière) Dear Reader I repositioned my paper to focus on man’s susceptibility to deception, and how that weakness prevents mankind from moving up the ranks, and maintains balance, of the Great Chain of Being. The structure of my paper flows like this: discussing that deception represents weak human nature; deception exists to determine man’s rank in the structure; without deception to keep man in his place, there would be cosmic chaos; humans cannot understand the relationships that exist in the heavenly world because deception prevents them from knowing the truth; and heavenly things (e.g. kings) are less blinded and more capable of resisting deception. Therefore, man’s ranking is appropriate and accurate, and should not be questioned. I definitely tried to analyze all the quotes I pulled from Pope and Molière’s works, and took out the ones that no longer supported my edited thesis. I included new quotes such as “’Tis but a part we see, and not a whole,” and “All this dread ORDER break—for whom? For thee? / Vile worm!—oh Madness! Pride! Impiety!” from Pope’s work. I think the latter of the two represents one of my best instances of analysis (Pope 350, 257-258) in this essay because I tried to look for an example that we did not ever discuss in class. Reading Pope’s Essay on Man again more carefully, I was able to recognize that “ORDER” was capitalized (which I never noticed before) and tried my best to figure out why Pope wrote in this particular way and used that particular word. I am more confident in my ability to analyze my evidence through this revision process, and I hope that my essay is more clear to the average reader than before. Sincerely, ENG 2850H – JMWH Blinded While Trying to See the Sun A vertically extended hierarchy of divinely designed power, from pathetic rocks at the bottom to an omnipotent God at the top, is known as the Great Chain of Being. This concept, first described by St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century—and later revisited in Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Man (Epistle I), and apparent throughout Molière’s Tartuffe—explains the permanent power concentrations of all things supernatural and natural in relation to each other. Interestingly, man is at a special threshold between the divine and the worldly. The ability to see and resist deception is what differentiates man from God. Man’s blindness to deception represents the weakness that explains and preserves his rank at this threshold—therefore, maintaining the balance of the whole structure. The theme of human flaws is a major driving force in Tartuffe. Without a prolific presence of mortal fragilities, Tartuffe would be incapable of practicing his scheming ways. Since Tartuffe is described as the ultimate malicious and faulty character (manipulative, cunning, hypocritical, and lustful), he may represent an absolute supernatural evil that works solely to exploit the weaknesses of man, or, simply, symbolize ultimate deception. He brings out and/or highlights the flaws of others: Madame Pernelle’s stubborn gullibility, which bookends the play; Dorine’s inclination to gossip and speak out of place/rank; Damis’ spying and violence; and Elmire’s vanity and use of deception. Tartuffe especially manipulates Orgon’s weaknesses throughout the play for Orgon is easily gullible and is blind to Tartuffe’s deception; he does not trust the words and opinions of his closest family members yet trusts a stranger; he does not hold 1 responsibility in and appropriate power over his household; he is the epitome of weak human nature! This vulnerability to deception must exist because they fit man into the divine plan. Pope informs us “Where all must full or not coherent be, / And all that rises, rise in due degree” (Pope 346.45-46). This declares that the Great Chain of Being cannot have any gaps, and that everything is placed and reorganized into where they belong according to God—however incomprehensible it may be to mankind. Pope uses rhyming couplets to encourage the reader to understand his overall message about the relationship between man and God, in the most playful and succinct manner. By repeating the word “rise”, Pope guides the reader to focus on the simplicity of his message, instead of using too many different, difficult, and wordy verses. The next lines, “Then…such rank as Man: / And all the question (wrangle e’er so long) / Is only this, if God has placed him wrong?” (346.47-50), end the stanza with a rhetorical question. A question is used to dare the reader to challenge God’s perfection by arguing against and questioning the rank of man. Both the writer and the reader know that to even question the rank that God, Himself, labeled for man is absolutely absurd; He does everything with a divine purpose and leaves no gaps or loopholes. Therefore, the question is not really asking for the answer. Since this weakness to deception is a debilitating factor in achieving perfection, humans are not and cannot ever be perfect. The line “’Tis but a part we see, and not a whole” (346, 60) explains man’s blindness to the whole truth. Because man’s vision is shaded, understanding God is simply beyond human ability. Since man can only comprehend the universe with regard to mortal constructions, he is “ignorant of the [greater] relations of systems and things” (344) to God by default. That is why when The Exempt first comes to Orgon’s residence before Orgon 2 can leave with Valere, Orgon immediately assumes he is in trouble. He cannot grasp the greater relationship between God and the king, and is excluded from the powers God shares with the king—powers of discernment, justice, and restoring order. This blindness to the truth reinforces man’s sensitivity to deception and incapability to comprehend the relation between the supernatural (e.g. kings and angels) and God. This lack of understanding keeps man from stepping beyond the threshold. In the 17th century, King James I of Great Britain mentioned in a speech to Parliament that the “state of monarchy is the most supreme thing upon earth, for kings are not only God’s lieutenants upon earth…but even by God himself are called gods” (Twyman). The Great Chain of Being supports why the king’s character in Tartuffe has greater power, and less fault, than ordinary men. The Exempt describes the king as one who “seeks into men’s hearts, / And cannot be deceived…” (Molière 196, 49-50). Because of his higher ranking—which dips into the heavenly realm—than man, the king is less blinded by deceit. The king has the ability to see through deception more easily than man, has greater wisdom, and holds greater power in restoring order and justice. The lines “And so divine justice nodded her head, / The king did not believe a word [Tartuffe] said” (196, 63-64) validates the fact that any characteristic of perfection comes from the highest power; in order for any other being/thing to possess great power, he/it can only do so with permission granted by God. Any power not given by God goes against divine will and results in great consequences (e.g. Tartuffe first transitions from a beggar to a “respected” man, only to later get arrested for his crimes and misdeeds). Again, this true rhyming couplet (“head” and “said”) allows the reader to gladly and clearly understand Pope’s overall message; the iambic meter makes his message sound natural and pleasant. 3 If humans were not blind to deception, it would break God’s rules of order and submission. Not only would it disrupt the power hierarchy, but also cause cosmic consequences: “All this dread ORDER break—for whom? For thee? / Vile worm!—oh Madness! Pride! Impiety!” (350, 257-258). The word “order” is capitalized, which places the heaviest importance on the very balance of the Great Chain of Being. It could also have the connotation of demanding attention to the severity of the situation, just as a judge calls for order in a courtroom. Also, by calling man a “worm” for breaking the power hierarchy, he is literally being casted down into one of the lowest ranks—for disrupting the balance leads to severe punishments. An example of the “madness” that is created from the “pride” that caused it, and the “impiety” that taints the world, is noted in the Christian Bible. The book of Genesis explains that God initially creates man and woman to roam and rule over the land in a carefree manner, knowing only of good. However, after disobeying God and eating forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge (of good and evil), God punishes Adam and Eve and every succeeding generation. He curses women with painful childbirth labor and submission to men; He curses men with painful toiling of lands filled with thorns, and painful toiling marked by a sweaty brow (New International Version, 3 Gen. 16-19). Therefore, in order to avoid extreme consequences set forth by the highest divinity, a certain blinded intended for humans are absolutely necessary. God grants mankind enough intelligence and power to rule over the natural world (e.g. animals, plants, rocks), but does not intend for humans to have the same amount of knowledge and power to rule in the supernatural world (e.g. angels, God). Therefore, God purposely gives man enough predispositions to deception in order to maintain order of the Great Chain of Being. Because of man’s rank in the power hierarchy, he is unable to understand any relationship that exists within the heavenly world. No matter how considerably man wants to be able to “see” (to 4 resist deception), even the measure of his own desire cannot cure his blindness—the sun will always be too bright for man no matter how intensely he tries to look at it. Because of this weakness, man will continue to remain in his intended rank—at the threshold between the mystical and the earthly. Works Cited: Molière. “Tartuffe.” The Norton Anthology of World Literature. Ed 3. Vol D. W.W. Norton & Company. 144-197. Print. New International Version. Biblica, 2011. Bible Gateway. Web. 23 Sept. 2013. <BibleGateway.com>. Pope, Alexander. “An Essay on Man: Epistle I.” The Norton Anthology of World Literature. Ed 3. Vol D. W.W. Norton & Company. Print. 344-351. Twyman, Tracy. “King James I.” The Dragon Society. Internet Archive: Wayback Machine. 2003. Web. 24 Sept 2013. <web.archive.org/web/20040610171143/www.thedragonsociety.com/Monarchy.html>. 5