From Balfour to Suez: Britain's Zionist Misadventure

advertisement

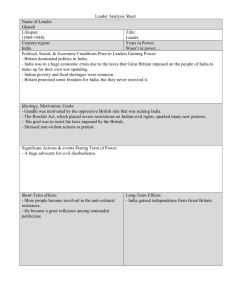

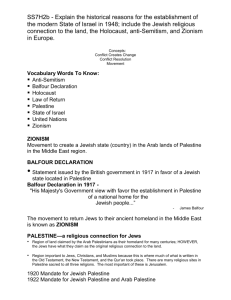

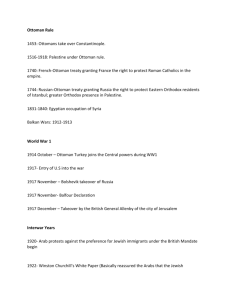

History Review December 2004 | Volume: 50 | Page 39-41 | Words: 1644 | Author: Carr, Robert Printable version From Balfour to Suez: Britain's Zionist Misadventure Robert Carr traces developments in British policy between 1917 and 1956. Despite coordinated Arab-British strategy and the heroics of T.E. Lawrence's Arab Revolt, 1918's defeat of the Ottomans did not bring political reward to the communities of the Middle East. Instead Britain and France had struck a secret deal in 1916 to carve up the region between them; and a year later Lloyd George's government had made further plans for a postwar Palestine. The Foreign Secretary of the day, Lord Balfour, conveyed these plans in a letter of 2nd November 1917 to Lord Rothschild: His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object … What lay behind this 'Balfour Declaration' and the government's push for a Jewish home in Palestine? Part of the answer lies in Anglicanism and its literal and sentimental approach to the Old Testament. Religious convictions lent sympathy to the 'chosen' Jewish nation. Another factor is the advent of Political Zionism (i.e. the hope to establish a Jewish homeland in Ancient Israel) which gained momentum largely as a result of the horrendous pogroms of 1881 and Tsar Alexander's endorsement of anti-Semitism. The active Zionism of high society figures such as Lord Rothschild and Chaim Weizmann further encouraged the British government. The Interwar years The League of Nations awarded Britain the Palestine Mandate in 1922; the mandate stipulated that Britain was 'responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish National Home'. Immediately, however, Britain attempted to renege on its responsibility. The Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, all but renounced the Balfour Declaration and restricted Jewish immigration. Furthermore, his White Paper saw Palestine divided, and two-thirds of the territory formally became the Arab emirate of Transjordan. While those hoping for the creation of a Jewish homeland were being squeezed by the British, Jews already living in Palestine were the victims of looting and murder as Palestinian Arabs revolted, initially in 1920 but followed up by further violence in 1921 and 1922. Zionists justifiably complained that the British failed to provide protection to Jewish settlers. The year 1929, however, saw the bloodiest massacres in Palestine: 133 Jews were killed. Somewhat insensitively, Colonial Secretary Passfield attributed such Arab violence to the provocation of Zionist land purchases and immigration! His 1929 White Paper introduced a severe limit on Jewish immigration (a reduction which became all the more important with the establishment of the anti-Semitic Nazi regime in Germany in1933). While Iraq and Egypt achieved effective independence, in 1932 and 1936 respectively, neither the Jews nor Arabs of Palestine were any closer to self-determination. In response to an Arab general strike and rioting in 1936, the British established an inquiry and, under Lord Peel, drew up a partition plan. The Palestinian Arabs flatly rejected the division of land. Britain had failed miserably to fulfil its mandate responsibilities: it was no closer to bringing either community to self-rule. Instead, British bungling had set Jews and Arabs against one another - with fatal consequences: 2,800 people were killed in massacres between 1936 and 1939. Remarkably, the (failed) Peel Plan had provided for Britain's indefinite rule over Jerusalem - more a sign of imperial arrogance than administrative competence. In seeking wider Arab support in an impending war with Germany, Britain introduced yet another White Paper. The 1939 White Paper declared Britain's intention to withdraw ten years hence; in the meantime it limited Jewish immigration to 15,000 each year (up to 1944 and thereafter only with Arab consent) and land sales to Jews were either prohibited or restricted across Palestine. The War and Postwar Years Despite British wavering over the 1917 Balfour Declaration and its mandate responsibility, 140,000 Palestinian Jews (men and women) volunteered for British military service. In addition, a Jewish Brigade Group was formed and saw action in Europe. Its members were concerned about the fate of their European cousins and sought to defeat Nazism. Knowledge of the Nazi Final Solution had reached Britain by the end of 1941. Requests to bomb either Auschwitz or its railway links were simply refused by the British. Instead government attitudes can perhaps be summed up by a senior wartime Foreign Office official: 'A disproportionate amount of time in this office is wasted in dealing with these wailing Jews'. Needless to say, while more than 6 million Jews were exterminated, there was no let-up on immigration restrictions to Palestine imposed by the 1939 White Paper. Two examples will help illuminate British policy. The Sturma, filled with children fleeing the Holocaust, was denied access to Palestine for two months before the ship sank, killing all but one of the refugees. Britain's intransigence was again evident in the notorious case of the Exodus which was loaded with pitiful Holocaust survivors, turned away from Palestine and forced back to Germany. Such refusal to provide shelter to targets of the Nazi Final Solution demonstrated that Britain had lost the moral authority to govern anyone - whether Jewish or Arab. The evident disagreements, terrorism and martial law of postwar Palestine meant that UNSCOP (United Nations Special Committee on Palestine) recommended termination of the mandate and the partition of land between Arabs and Jews. For their part, the Jews of Palestine grabbed statehood with two hands: Israel was thus born on 14th May 1948 - the eve of British withdrawal. Britain left behind two communities in bitter dispute: the mandate period set in motion the long years of Arab-Israeli conflict. The Suez Crisis Britain next dipped its toes back in the Middle East in 1955. For its role in the cold war, Britain sought to keep the Soviet Union at bay in the region through the Baghdad Pact. This was a British-led alliance of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Pakistan. On the other side of the political fence sat President Nasser of Egypt. Nasser had formally recognised newly Communist China and was the beneficiary of Soviet weaponry. In July 1955 he announced the forthcoming receipt of 200 modern bombers and other Soviet armaments. What prompted British conflict with Egypt, however, was Nasser's seizure of the Suez Canal in October 1956. Nasser sought to raise finance for his ambitious Aswan Dam project. Failure to secure foreign loans meant he turned to a source of great revenue within Egypt itself - the Suez Canal, which he proceeded to nationalise. Under the terms of the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, Britain was to maintain a military base at Suez for the next 20 years. As the main east-west shipping route and the carrier of a quarter of all British imports, the canal was crucial to British interests. In conjunction with France, Britain hatched a plot against Egypt using Israel. Egypt was not only an avowed enemy of the Jewish state but had denied it access to the Red Sea at Israel's southern tip. Israel had long wanted to remove this illegal blockade and, moreover, had been on tenterhooks since the Soviet arms influx into Egypt and the recent establishment of a joint Egyptian-Syrian military command. Britain (with France) planned that Israel should attack Egypt: Israeli forces were to reach as far as the Suez Canal, and at this point, Britain would 'intervene' to protect shipping and thus (re)take control of the canal. In military terms, Britain's plans worked out: Israel met its objectives and the British bombed Egyptian air bases and occupied the northern section of the canal. In wider terms, the Suez Crisis proved a political blunder and grave diplomatic gaffe. Despite tacit support from President Eisenhower, Prime Minister Eden was requested to delay any action against Nasser until after the American presidential elections of 6th November. Britain ignored such advice and suffered UN condemnation, a veiled threat from the Soviet Union and the imposition of US economic sanctions. Consequently Britain was forced to withdraw from Egypt with its tail between its legs. This was no mere humiliation confined to Egypt, however: the Baghdad Pact was effectively over as was the Anglo-Jordanian Treaty. Unwittingly, such imperialist aggression provided the Soviet Union with a considerable political victory: Suez displayed Anglo-French impotence and thus created a power vacuum in the Middle East. The Soviet Union proved the best able to fill such a void. Tragically, both the cold war and superpowers' arms race were added to the troubles of the Arabs and Jews. Soviet sponsorship of Egypt was stepped up and Syria was soon similarly armed and advised. America later came to rely on Israel to redress the strategic balance: over a short period of time (from Kennedy's presidency) Israel was pumped full of American weaponry and funding. The seeds for the third and fourth Arab-Israeli wars had very much been sown by the fiasco of 1956. More than a failure of imperialism, Suez showed that Britain had lost its independence in terms of foreign policy. Hugh Thomas judged in the 1960s that 'the British have never since ventured on a foreign policy independent of the USA'. It was, arguably, a new low in Britain's policy relations with the Jews of the Middle East. Only years before, Britain had failed to protect Jews against Arab and Nazi violence. Moreover, Britain's handling of, and withdrawal from, Palestine made bloody Arab-Israeli confrontation inevitable. And yet still, in 1956, Britain was prepared to use Israel for its own ends. This last hurrah for the empire displayed evident double standards. The period 1917-1956 saw government policy swing between promise and punishment to the Jews. Relations with the Jews of Palestine and Israel eroded the idea of Britain as an enlightened power. Imperial insensitivity, ineptitude and arrogance characterised Britain's Zionist misadventure. Further Reading: Arthur Goldschmidt Jr., A Concise History of the Middle East (Westview Press, 1999) Walter Lacqueur and Barry Rubin (eds), The Arab-Israel Reader (Penguin, 1984) Hugh Thomas, The Suez Affair (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1967) Robert Carr lectures in history at Spelthorne College and is a research supervisor in international relations at the American University in London.