Is there a Doctor or Nurse on Board this Aircraft?

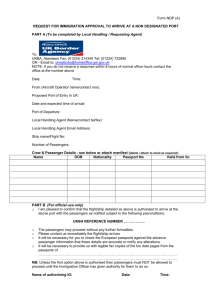

advertisement

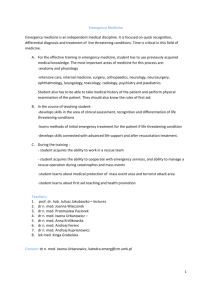

“Is there a MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL ON BOARD this aircraft?” Challenges at 35.000 ft Linda E. Pelinka, MD, PhD Medical University of Vienna and Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Experimental & Clinical Traumatology Vienna, Austria, European Union TRAUMA Basics Pathophysiology Medical Equipment Common problems Emergencies Legal Aspects Basics Statistics Worldwide, ~1 million people are traveling by air at any given time >700 million Americans travel by air in the US ~one per 10-40,000 passengers will experience an medical emergency. U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. Moving America safely: annual performance report 2005. http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic Sand M et al. Surgical & Medical Emergencies on board European Aircraft:10189 cases. http://ccforum.com/content/13/1/R3 >50% of passengers age 50 or over have at least one health issue(s) Emergencies will become more frequent as % of elderly increases Goodwyn T: In-flight Medical Emergencies: an Overview. Brit Med J 2000; 321:1338-41 There are more deaths from in-flight medical emergencies than from airline accidents. In 2006: 550 medical diversions 59% were 50 or older 63 passengers died in-flight National Transportation Safety Board and Med Aire In the Air, Health Emergencies rise quietly USA TODAY, Dec 2008 The death of an AA passenger flying from Haiti to NYC has cast a spotlight on the growing number of medical emergencies on commercial jets, a trend that has escaped public notice because airlines aren’t required to report such incidents. A MedAire analysis shows that such incidents nearly doubled from 2000-2006, from 19 to 35 per million passengers. 1 of 2 In the Air, Health Emergencies rise quietly USA TODAY, Dec 2008 According to analysts, this is due to 2 factors: 79 million baby boomers are entering retirement, but continue traveling habits established when they were young. Flights are going farther and lasting longer. Av. length of a flight in 2000: 1,233 mi Av. length of a flight in2006: 1,347 Max flying time today: 20 hrs 2 of 2 “if you are ill, an airplane is the worst place to be… “… you are trapped at 35,000 ft.” David Stempler President of the Air Travelers’ Association. Pathophysiology Setting on Board: passenger’s point of view Very cramped everywhere (seat, restroom) Three-dimensional motion of aircraft Very dry Dehydration Hemoconcentration & hyperviscosity increase risk of thromboembolism The mild hyperbaric changes during flight are sufficient to cause increased activation of coagulation in healthy individuals with no thrombophilia compared with that in individuals seated and not moving at ground level. Toff WD et al: Effec of hypobaric Hypoxia, simulating Conditions during long-haul air travel on Coagulation, Fibrinolysis, Platelet Function and Endothelial Activation. JAMA 2006; 295: 2251-61. Humidity Low, typically 10-20% Low humidity has a propensity to exacerbate reactive airway disease and dehydration Hocking MB: Passengr Aircraft Cabin Air Quality: Trends, Effects, SocietalCosts, Proposals. Chemosphere 2000; 41:603-15 Commercial cruising altitude 7010-12,498 m Cabin Pressurization to 2438 m: What happens? Atmospheric cabin pressure drops PaO2 drops from 95(12.7 kPa) to 65mmHg (8.7 kPa) Oxyhemoglobin sat drops from 95-100% to 90% Humpreys S et al: Effect of high Altitude Commercial Air Travel on O2 Saturation. Anesthesia 2005; 60: 458-60 The passenger cabin is pressurised to 1524— 2438 m. This reduced pressure within the passenger cabin results in lower syst. PaO2 and oxyhaemoglobin (oyxhb). For most healthy passengers, this results in a decrease in the arterial partial pressure oxygen tension. Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Passengers with preexisting lower sea-level oxy-hb sat have greater declines during flight. E.g., a passenger with mild COPD with a sealevel PaO2 of 70 mm Hg PaO2 to about 53 mm Hg or oxy-hb sat of approximately 84% at a cabin altitude of 2438 m Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 8 7 6 5 4 Altitude in km pO2 Drop at various Altitudes pO2 drop by ~30 mmHg between sea level and cabin press. level (2400m) vs ~4 mmHg between 6000-8000m) 30 32 34 38 45 54 3 61 69 2 1 0 73 81 89 pO2 in mm Hg 20 40 60 100 80 100 120 mod acc to Stueben, U. Flugmedizin Med. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsges. Berlin, 2008 low cabin pressure lower alveolar pO2 (55-70 mmHg) lower arterial pO2 (~90%) increasing edema Curdt-Christiansen, C. et al: Principles and Practice of Aviation Medicine. World Scientific, London, 2009. Effect of Aircraft-Cabin Altitude on Passenger Discomfort Muhm JM et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 18-27 The frequency of reported complaints associated with acute mountain sickness (fatigue, lightheadedness and nausea) increased with increasing altitude and peaked at 2438 m. Most symptoms became apparent after 3-9 hrs of exposure. Cabins in new Airbus A380, Boeing 787, pressurized at 1829 m Hypoxia Preexisting cardiac Cabin pressure and/or pulmonary and/or psychological issues Mild Hypoxia 68-Year-)ld woman with Chest Pain during an Airplane Flight Picard, MH et al. New Engl J Med 2010; 363/27: 2652-61. History of hypertension and hyperlipidemia Flight from the Middle East to Europe: Gradually developing chest pain and pressure, fluctuating intensity, not radiating. Resolves spontaenously after several hours Subsequent flight Europe to U.S.: Chest pain recurs. Is Air Travel Safe for those with Lung Disease? Coker RK et al. Eur Resp J 2007; 30: 1057-63 This prospective, observational study showed that 18% of passengers with COPD have at least mild respiratory distress during a flight. Cramped Space & Immobilization Have been linked to 75% of all air-travel cases of venous thromboembolism Greatest frequency of theomboembolism in non-aisle seats Cesarone MR et al: Venous Thrombosis from Air Travel: the LONFLIT3 Study – Prevention with Aspirin vs LMWH in high-risk subjects. Angiology 2002; 53: 1-6. Thromboembolism Risk peaks up to four-fold when flight duration >8 h Risk factors: Dehydration, immobility, hypobaric hypoxia, obesity, malignancy, recent surgery, h/o hypercoagulable state Oral contraceptives increase risk 16-fold Business vs coach class no effect on incidence Aryal KR & Al-Khaffaf H. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; 31: 187-99. Jacobson BF et al. S Afr Med J 2003; 93: 522-528. Boyle’s Law The volume occupied by a gas is inversely proportional to the surrounding pressure. Thus, at cruising altitude, gas in body cavities expands by 30%: Boyle’s Law & Barotrauma Healthy passengers minor abdominal cramping, ear pressure Passengers after recent surgery Bowel perforation, wound dehiscence Guidelines Delay flying for 12 h after scuba diving (1 dive) w/o deco 24 h after several dives or 1 dive + deco 7-10 dys after diverticulitis 2 wks after major surgery Medical Guidelines for Airline Travel, 2nd Edn. Aviat Space Environ Med 2003; 74 (suppl): A1-A19 Boyle’s Law & Effect on Medical Equipment Gas expansion in Pneumatic splints Urinary caths Feeding tubes ET tubes (instill water instead of air) Medical Equipment Emergency Medical Kit Device Stethoscope Blood pressure cuff Bag-mask resuscitator 1 required, child/infant optional Oral airways 3 sizes required Emergency Medical Kit Drug Nitroglycerin 10 tablets min. Aspirin 4 tablets min. Albuterol 1 metered-dose inhaler Dextrose 50% 25g min. Oral Antihistamines 4 tablets min Iv Antihistamines 2 amps min Iv Epinephrine 1:1000 2 mg min (allergic react.) Emergency Medical Kit Cardiac Resus Drugs Iv Epinephrine 1:10,000 2 mg total min Atropine 1 mg total min Lidocaine 200mg total min Emergency Medical Kit Device opt. provided on intercontinental flights: Tempus IC State of the Transmits info incl digital pics, art telemed video to ground based monitor physician Automated BP cuff, glucometer, capnometer, 12-ld ECG, pulse oximeter Provides on-screen, step-by-step instructions Opioids - Nalbuphine and Morphine – are provided by some carriers Emergency Medical Kit Drugs optionally provided on intercontinental flights Ondansetron Nalbuphine ! Naloxone Oxygen Masks and nasal tubes available on board. Emergency bottles provide O2 at a fixed rate of 4 liters/min. Sufficient for 75 min. Medication and technology are expensive but may still be cost-effective Diversion can cost from US$10,000 to $100,000 depending on the route Equipment Challenges Auscultation (pulm., BP) difficult due to ambient engine noise. Alternative: radial pulse palpation for syst BP. Aviation portable O2 bottles have only 1 of 2 settings: “low”=2 l/min and 4 l/min=“high flow”, far lower than flow used for EMS. O2 tubing for bag-valve resuscitation are not required to be compatible with these on-board O2 bottles. Equipment Challenges AEDs on board not required to have ECG screen, though ACLS meds are provided. When AED does have screen, it is limited to a leads II/paddles view. Glucometers not mandatory, though 50% dextrose is. Ask if any passenger on board would be willing to share personal glucometer. Equipment Challenges Since 9/11, phones have been largely removed from cabins and cockpit doors have been secured. Info must be relayed via intercom from the back of the plane or via flight attendant’s headset to pilots, who then relay info to doctors on the ground AED Automated External Defibrillator AA first US airline to equip its fleet in 1997, first cardiac arrest save 1998. Mandatory for US commercial carriers. (Aviation Medical Assistance Act). Aircraft with inoperable AEDs are allowed to make “a few flights” until a replacement can be found. AED Automated External Defibrillator AEDs are still not mandatory for European commercial carriers (European Aviation Safety Agency). No AEDs on Intercity aircraft in Europe. Positioning the Patient Remove patient from seat, gripping him/her from behind. Positioning the Patient If possible, position potential emergencies next to the aircraft’s door or in the galley, horizontal to flight direction against front wall. Make sure all trolleys are secured. Stueben, U. Flugmedizin/Flight Medicine. Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Berlin, 2008 Make sure there is enough space behind pat’s head in case of intubation Make sure there is enough space beside pat’s chest in case of cardiac massage Telemedicine: MedAire Ground-based service utilized by airlines. VHF radio or satellite phone contact to ED physicians at MedAire. Arizona-based company providing emergency med advice to airlines carrying ~half of the 768 million passengers on US flights each year. Takes responsibility for deciding if flight diversion is appropriate. Medical Diversion Pilot’s decision only Depends on weather, appropriate airport facilities, terrain, landing weight, fuel: e.g. impossible right after take off: Weight of aircraft + full tanks exceeds max weight for landing (e.g. take off NYC, earliest landing Boston) Flight diversions due to onboard medical emergencies on an international commercial airline. Valani R et al, McMaster University, Hamilton General Hospital, Ontario, Canada. Aviat Space Environ Med 2010; 81: 1037-40 5386 telemed contacts/5yrs. Av. 2.4 diversions recommended/100 calls Telemed decrease 2006-2007 was accompanied by an increase in diversions. 1 of 2 Flight diversions due to onboard medical emergencies on an international commercial airline. Valani R et al, McMaster University, Hamilton General Hospital, Ontario, Canada. Aviat Space Environ Med 2010; 81: 1037-40 Most common causes for diversion Cardiac (26%) Neurological (20%) Gastrointestinal (11%) Syncope (10%) 2 of 2 Telemedical Assistance for in-flight Emergencies on Intercontinental Commercial Aircraft Weinlich M et al, Dept of Trauma Surgery Goethe Univ. Frankfurt, Germany. J Telemed Telecare 2009; 15: 409-13 3-yr prospective study, commercial airline Medical incidents: n=3364 Use of telemedicine: 9% (n=275) Most cases were middle aged, not elderly Neurological, non-psych telemed cases:27% (n=83, 27 required diversion, 275 did not. No non-diverted patient deteriorated Pediatric emergencies on a USbased commercial airline Moore BR et al, Dept of Ped. & Adolscent Med, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, NY. Pediatri Emerg Care 2005; 21: 725-9. 7-yr retrospective study, commercial airline 1 ped call per 20,775 flights 2/3 calls in-flight, 1/3 pre-flight Mean age 6 yrs Most common complaints: infectious disease, neurological, respiratory emergencies. Common Problems How common are medical problems during flight? Minor medical problem not requiring medical assistance: every150th passenger Medical care: 1 of 10.000 passengers Medical emergency: 1 of 50.000 passengers (~6% cardiac) Time Zone Changes & altered Meal Times Hypoglycemia in insulin dependent diabetics though diabetic meals can be provided. Passengers on other strict drug regimens, (e.g. for epilepsy) Passengers who have packed their medication in the hold. Fear of Flying Unruliness (aggravated by alcohol) Psychovegetative dysregulation: tachycardia, sweating, hypotension (aggravated by sedatives and/or dehydration) Dehydration Prolonged sunbathing and/or partying on last day of vacation Dehydration (e.g. hot location, last minute rush/stress, lack of foreign currency to buy drinks) Cabin pressure Dehydration & Dry Atmosphere Dry cabin atmosphere irritates mucous membranes Duration of flight exacerbates dehydration Drinking alcohol exacerbates dehydration. Altitude enhances the effect of alcohol, contributing to “air rage,” Air Rage hours of dry cabin atmosphere irritate mucous membranes Drinking extra fluid helps, Drinking alcohol opposite effect. Intoxicating properties enhanced at altitude. smoking ban in nicotine addicts. Motion Sickness Symptoms Apathy Pallor Sweating Over-sensitivity to noise, smell Hypersalivation Aggravation Alcohol Turbulence Sudden de- or acceleration Noise, smells Heat Vaso-Vagal Syncope 40 % of cardiovascular emergencies on board are syncopes. Most common causes: motion sickness, dehydration, fear of flying. Responding to in-flight Medical Events 1 Be prepared to show med credentials or answer questions about degree or training Obtain consent from affected passenger. Assume implied consent when passenger is incapacitated or unresponsive. Do not fear litigation. Physicians have been deposed, but no litigation has ever been brought forward against a responding physician. Responding to in-flight Medical Events 2 Request and establish communication with the airline’s ground med support for advice and consultation regardless of how minor or serious the in-flight event is. Request the enhanced emergency med kit (many airlines initially offer basic first-aid kit) but do not open it unless needed. Each kit has a placard listing contents. Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Hypoglycemia If conscious, administer oral glucose gel If unconscious, establish iv access Adult: administer D50 dextrose (1 amp) Child: dilute D50 dextrose 1:1 with normal saline to prepare D25 dextrose and administer 2 ml/kg Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Motion Sickness: What can you do on board? Move patient to seat in the middle of the plane Keep head steady Eyes shut No alcohol Metoclopramide Dimenhydrinate Scopolamine patch Vasovagal Syncope Lay pt supine Elevate legs Apply cold compress to forehead Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Emergencies Altering Cabin Pressure Cabins are pressurized but airlines can legally alter pressure to the equivalent of 8000 ft. Emergencies in the Air Qureshi A, Porter KM. M. Emerg Med J 2005; 22: 658-59. Exacerbation of pre-existing medical problems caused the vast majority of in-flight emergencies (65%). Respiratory problems were most common. 50% asthma-related, 33% due to forgotton medication. Syncope accounted for 25% of all incidents and 91% of all new medical problems. Hypertensive Crisis Urapidil available on all aircraft Nitro Spray and/or capsules available on all aircraft Oral calcium antagonists available on some aircraft Consider Diff Dg: Stroke, MCI, hemorrhage from ruptured aneurysm, thus Medical diversion if possible Tachycardia Positioning, oxygen, iv Amiodarone 2 150mg amps Lidocaine 1-1.5 mg/kg Last ditch measure: Defibrillation AED will not discharge below ventricular tachycardia of 180 because its automatic rhythm-detection is programmed accordingly. Arrhythmia Horizonal positioning aisle, galley, business class seat I.V., fluid, oxygen Monitoring with AED Sedation Have CPR ready Suspected Myocardial Infarction O2, Aspirin 325mg po Nitroglycerin 0.4 mg subling every 5 min up to three doses or Morphine sulfate 3 mg iv or im. Request cabin altitude reduction to increase cabin pressure Some airlines carry AEDs with a cardiac rhythm display to help assess rhythm. Cardiac Arrest Place AED on patient. Some defibrillators incorporate a rhythm display that can help making decisions Follow BLS or ACLS resus algorithms If resuscitation is stopped because of no return of spontaneous circulation, pt should not be pronounced dead officially on international flights (medico-legal reasons) Silverman D, Gendeau M. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 US Government Air Carrier Access Act May 2008 All US-based air carriers and foreign air carrier flights that begin or end in the USA must accommodate passengers who need portable oxygen concentrators. Non-discrimination on the basis of disability in air travel. Final Rule. Fed Regist 2008; 73:27613-27687. Bronchial Asthma or COPD Administer O2 and inhaled bronchodilator (2 puffs per 15 min) Request reduction of cabin altitude to increase cabin pressure Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Pneumothorax The effect on pneumothorax was well publicised when, on a flight from Hong Kong to London, Professor Angus Wallace relieved a tension pneumothorax with the aid of a catheter, coat hanger, and brandy bottle. Wallace WA: Managing in flight emergencies. BMJ 1995; 311:1508 Acute Allergic Reaction Diphenhydramine po, im or iv. Adults 25-50 mg, peds 12.5 mg. Severe generalized urticaria, angio-edema, stridor or bronchospasm Epinephrine: Adults 0.3-0.5 ml, peds 0.01 ml/kg/dose 1 in 1000 solution im or sc every 510 min as needed. 3 doses in adults, up to 3 doses in peds. Additonal fluids in anaphylaxis Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Acute Abdominal Pain Consider administering antacid Request cabin altitude reduction to increase cabin pressure. That increases oxygenation & decreases gas expansion. Administer paracetamol or ibuprofen. Some kits include morphine. Consider administering an anti-emetic. Some kits include Ondansetron. Silverman D, Gendeau M. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Acute Agitation or Misconduct Look for med causes (hypoxia, hypoglycemia) If administering a benzo, be aware of poss oversed (passenger taking several substaces) If physical restraint is needed, place restrained individual in left lateral position Monitor when using chemical or physical restraints. High risk of complications in exerted, agitated passengers fighting restraints: hypoxia, metabolic acidosis, sudden death. Silverman D, Gendeau M. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Seizure Keep pt away from nearby objects Do not place anything in pt’s mouth Administer Diazepam 0.1-0.3 mg/kg iv or im for pediatrics, 5 mg iv or im for adults Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Extended travel with limited movement & rehydration are THE recipe for pulmonary embolism. Add factors like birth control pills, obesity, age and/or smoking and you are pretty much an event about to happen. Anticoagulants for Air Travel? No formal guidelines exist Still controversial, though RC trials show benefit of LMWH for air travelers at moderate risk who do not take anticoags Aspirin is not recommended alone as prophylaxis for any air traveler. Kuipers S et al: Travel and venous Thrombosis: A systematic review. J Intern Med 2007; 262: 615-634. Sudden Loss of Consciousness Differential Diagnosis Vasovagal syncope Asystole Hypoglycemic shock Apoplectic ischemic/hemorrhagic stroke Epileptic seizure Intoxication (drugs, toxic agents) Unresponsive Passenger Place automated external defibrillator pads on pt Establish iv access Administer O2, D50 dextrose (1 amp) iv for adult or D25 dextrose (2ml/kg) for pediatric, Naloxone 0.1-2 mg iv or im (available on some flights) Follow BLS or ACLS resus algorithms Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Consider Diversion Acute coronary syndrome Chest pain Severe dyspnoea Severe abdom pain that doesn’t improve Severe agitation Stroke Refractory seizure Persistently unresponsive passenger Silverman D, Gendeau M. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Legal Aspects Does a medical professional who is a passenger have a duty to volunteer medical assistance? US, Canada and the UK: NO, unless there is a pre-existing patient relationship. International law: country in which aircraft is registered has jurisdiction. However, country in which incident occurs and country of citizenship of plaintiff or defendant can also have jurisdiction. Hedouin V et al: Medical Responsibility and Air Transport. Med Law 1998; 17: 503-6. Medicolegal Recommendations 1. Identify yourself, state your medical qualifications. Some airlines require proof of your medical qualifications. 2. Obtain as complete a history as possible, inform passenger and family members (if present) of your impression, obtain consent before initiating any form of examination or treatment. Assume implied consent if pg. is incapacitated. Gendreau MA, DeJohn C. N Engl J Med 2002; 346/14: 1067-73. Medicolegal Recommendations 3. If consent has been given, carry out an appropriate physical examination. 4.Request an interpreter if the passenger you are assisting does not speak your language. 5. Inform flight crew of your impression. 6. If condition is serious, request aircraft to be diverted to nearest appropriate airport. Medicolegal Recommendations 7. Establish communication with on-ground med support staff, if available. Respect ground-based physician’s expertise & experience in managing in-flight medical events. 8.Document in writing your findings, impression, treatment, and communication with flight crew & on-ground med support. 9. Do not use any treatment that you do not feel confident administering. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act Passed by Congress in 1998 Specifically protects physicians, state-qualified EMTs, paramedics, nurses and physician assistants. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act “ An individual shall not be liable for damages in any action brought in a Federal or State court arising out of the acts or omissions of the individual in providing or attempting to provide assistance in the case of an in-flight med emergency unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct.” The Aviation Medical Assistance Act Limits liability for volunteering physicians under the assumption that they act in good faith, receive no monetary compensation and provide reasonable care. Gifts, such as seat upgrades and liquors are not considered compensation. Pertains to events that occur within US airspace and aircraft registered within the US. Many airlines indemnify volunteering physicians. Written confirmation is provided by the captain upon request. Cocks R and Liew M: Commercial Aviation, in-flight Emergencies and the Physician. Emerg Med Australas 2007; 19: 1-8. Medicolegal Recommendations Keep in mind that “good Samaritan” statutes protect you only from liability for actions that other competent persons with similar training would take under similar circumstances. Gendreau MA, DeJohn C. N Engl J Med 2002; 346/14: 1067-73. Never officially pronounce a passenger dead, even if you assess that resuscitation is futile and cease treatment, especially on international flights. Silverman D, Gendeau M: Medical issues associated with commercial flights. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Up in the Air – Suspending Ethical Medical Practice Shaner, M. New Engl J Med 2010; 363/21: 1988-89. We were flying from the East Coast to the West. About midflight, a lady behind us reached frantically for the baggage bin. She was trying to get her husband’s oxygen tank. He looked about 70, eyes closed, right hand clutching his chest, grimacing in pain. Suddenly, his grimace faded and his arm dropped. Leaning over, I felt for a pulse. There was none. A flight attendant approached. “I am a physician,” I said. “Let’s get him down to the floor.” Up in the Air – Suspending Ethical Medical Practice Shaner, M. New Engl J Med 2010; 363/21: 1988-89. We were flying from the East Coast to the West. About midflight, a lady behind us reached frantically for the baggage bin. She was trying to get her husband’s oxygen tank. He looked about 70, eyes closed, right hand clutching his chest, grimacing in pain. Suddenly, his grimace faded and his arm dropped. Leaning over, I felt for a pulse. There was none. A flight attendant approached. “I am a physician,” I said. “Let’s get him down to the floor.” Up in the Air – Suspending Ethical Medical Practice Shaner, M. New Engl J Med 2010; 363/21: 1988-89. We lifted him into the aisle. I shined a pocket flashlight on the dimly lit scene. He had stopped breathing; no pulse. Three other passengers joined us, an anesthesiologist, an oncologist and a surgeon. My wife ran the code, I provided chest compressions, the anesthesiologist bagged the patient, the oncologist managed the equipment, the surgeon put in an i.v. and then injected epinephrine intracardially. Up in the Air – Suspending Ethical Medical Practice Shaner, M. New Engl J Med 2010; 363/21: 1988-89. We followed the protocol suggested by the AED. It did not discharge: its rhythm-detection program found no rhythm that might be treated with defibrillation. The monitor showed a wide complex bradycardia with which we could not associate a palpable pulse. After 25 minutes of basic cardiac life support, there was still only pulseless electrical activity. The 5 physicians agreed:it was time to stop and declare the patient dead. Up in the Air – Suspending Ethical Medical Practice Shaner, M. New Engl J Med 2010; 363/21: 1988-89. The flight attendant explained that if we stopped CPR, the airline’s protocol would require the cabin crew to continue it. In other words, CPR was going forward whatever we decided. We chose to continue it ourselves so that the four flight attendants could attend to their duties during an emergency landing. We landed 45 min later. The patient died the same day. TAKE HOME MESSAGES Dehydration Low Humidity Mild Hypoxia Boyle’s Law Pre-existing med Condition Keep in mind that airlines can legally alter pressure to the equivalent of 8000 ft. Consider Diversion Acute coronary syndrome Chest pain Severe dyspnoea Severe abdom pain that doesn’t improve Severe agitation Stroke Refractory seizure Persistently unresponsive passenger Silverman D, Gendeau M. The Lancet 2009; 373/9680: 2067-77 Keep in mind that “good Samaritan” statutes protect you only from liability for actions that other competent persons with similar training would take under similar circumstances. Gendreau MA, DeJohn C. N Engl J Med 2002; 346/14: 1067-73.