Historical Macbeth

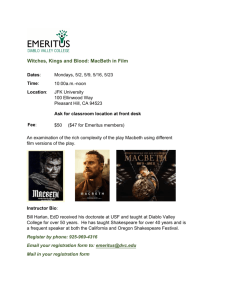

advertisement

Mark Nicholls sets off on the trail of the ancient Scottish king, Macbeth, to discover his true character Macbeth is one of the greatest and most mysterious characters in Scottish history; his reign shrouded in myth, folklore and misinformation. As an 11th century Scottish king, his reign was relatively long at 17 years, but his achievements and deeds have been tarnished by the pen of the greatest of all English playwrights, William Shakespeare, in his ‘Scottish Play’. Admirers of Richard III (1483-85) of England know only too well what impact the pen of Shakespeare had on transforming historical fact. Yet it is with Macbeth, and all the theatrical superstitions that now accompany the play, that the Scottish king’s reputation has been rewritten, despite the efforts of historians to convince people otherwise. But who was Macbeth? When did he reign, and was he the tyrant that theatrical history has created? His full name was Mac Bethad mac Findlaich and he was born in what is now Dingwall in 1005. His father was Finlay, the Mormaer – High Steward and Earl – of Moray. His mother is believed to have been Donada, who was the second daughter of Malcolm II, who was King of Scots between 1005 and 1034. Dingwall lies north of the Highland capital, Inverness, and owes its name to Norwegian Vikings who ruled northern Scotland from about the end of the ninth century. It has a long history, much of it told via the Dingwall Heritage Trail that can be walked within 90 minutes taking in Dingwall Townhouse, memorials, churches and the Castle Doocot. Finlay died in 1020, but it was not until 1032 that Macbeth became the ruler of Moray after his cousin Gille Coemgain and about 50 followers were burned to death having been trapped in their stronghold. These were violent times. Evidence is limited as to who was the perpetrator, though Macbeth was the person with most to gain from the atrocity. Macbeth, who is also said to have been one of the great Scottish nobles to submit to King Canute of England when he travelled north, truly comes to the attention of the pages of history in August 1040. It was at that point that he became King of the Scots when he killed the then King, Duncan I (1034-1040), in a battle at Pitgaveny, near Elgin in Morayshire. While we know that Duncan died in battle, there is no historical indication that he was actually killed by Macbeth, as Shakespeare’s text suggests. Malcolm strengthened his claim to the throne of Scotland when he married Kenneth III’s (997-1005) grand-daughter Gruoch, the widow of Gille Coemgain. In a further battle in 1045, he defeated and killed Duncan I’s father at Dunkeld on the banks of the River Tay near Perth. Despite the portrayal of Macbeth as a murderer and tyrant, history tends to reflect a more just rule during what was the latter period of the Dark Ages in Scotland. He imposed law and order and encouraged the development of Christianity. In 1050, he made a six-month pilgrimage to Rome for a Papal Jubilee during the reign of Pope Leo IX. Historians have read much into this journey. Any king able to leave his kingdom for such a period of time and distribute money in Rome was a monarch who reigned over a land that was politically and economically stable for the time, that there was no serious challenge to the throne, and that Macbeth had earned the respect of his subjects. Shakespeare wrote his play in the period 1604-06, just after the Stuart king James VI of Scotland had become James I of England. Where the real story of Macbeth becomes clouded is in the interpretation of some medieval chronicles which most likely provided William Shakespeare with the basis for his play, a masterpiece of drama shrouded in superstition to the extent that, for good luck, it is only ever spoken of in the theatre as “the Scottish play.” From these texts, several mythical events are associated with Macbeth. Most notable is the encounter with three “weird sisters” – later the three witches of Shakespeare’s play. In fact, the Shakespearean interpretation has so frustrated historians that in 2005, on the 1000th anniversary of his birth, a group of historians and politicians began a campaign to rehabilitate Macbeth, claiming that his reputation has been unfairly maligned. The drive to dispel the Scottish King’s image as an evil murderer, whose name has become synonymous with bad luck and superstition even persuaded politicians in the Scottish Parliament to sign a motion calling for Macbeth’s achievements to be recognised. Dr James Fraser from Edinburgh University’s history department said: “He was certainly not the murderer that Shakespeare portrays, nor the tyrant. The play drew from a long-standing conviction among medieval Scottish historians that Macbeth was not entitled to claim the Scottish throne, and so, in claiming it, he had committed a terrible crime. “This is not to say that the man was lilywhite from our own moral perspective. He seems to have believed that he was entitled to the kingship of Scotland, and, like a forerunner of Robert Bruce, he was prepared to take drastic measures in order to stake that claim. “The other kings of Scots in the 11th century behaved in a similar way – killing kinsmen and putting down rivals. There is little evidence that the Scots at large objected in principle to Macbeth’s capture of the kingship in 1040. This was still to some extent a time when the strong took what they wanted.” Dr Fraser said Macbeth’s reign (1040-57) is mainly shrouded in mystery, on account of the non-survival of the kind of written sources that would help to shed light on it. “We can’t prove he wasn’t a tyrant, anymore than we can prove he was,” he added. “But there’s one bit of evidence to suggest that things were pretty stable in Scotland during his reign: Macbeth’s pilgrimage to Rome in the 1050s. “That would have required him to be out of the country for many months, and perhaps as long as a year, and he must have felt he had a pretty solid grip on things in order to contemplate such a journey.” In military terms Macbeth, who was regarded by the ancient Highland clans as the last great Celtic ruler of Scotland, had a reputation as a brave and successful leader with forays across the border into Northumbria in England. Macbeth had made an enemy of Siward, who was the earl of Northumbria and one of the three most powerful men in England at the time. Siward was supporting attempts to return Duncan’s son Malcolm Canmore – who was also his nephew – to the throne of Scotland. The first serious challenge came in 1054 close to Dunkeld, an area surrounded by wooded hills and crags. Malcolm used this terrain as a base to attack Macbeth at Dunsinnan and though he inflicted a defeat on the king, Macbeth was able to flee and re-group. It was three years later that Macbeth’s reign came to a bloody end in the same way as it had started, on the battlefield. In August 1057, as he headed to meet reinforcements at Forres, he stopped with his men to rest and get water from the well at the tiny village of Lumphanan in Aberdeenshire. While doing so, he was surrounded by Malcolm Canmore’s forces and defeated and captured. Close to the village is the site of the battle and the stone where Macbeth was beheaded. A small cairn now marks the spot. His body was believed to have been buried nearby and later removed to Iona for burial with other Scottish kings, though that is disputed locally by the suggestion that his headless corpse was buried in St Finan’s churchyard in the village. Macbeth was succeeded by his stepson Lulach (1057-58), but within a year Canmore had become Malcolm III (10581093). Macbeth was no more or less brutal or murderous than any other ruler of this time. Yet it remains William Shakespeare’s theatrical portrayal of him that has seen his character forever tarnished. MLA Citation: Nicholls, Mark. "The Scottish King (Macbeth)." Scotland Apr. 2007: 24-25. Scotland Magazine Issue 32. Apr. 2007. Web. 04 Jan. 2016.